看展览 Exhibition

预告片 Trailer

展览影片 Exhibition Tour

艺术家影片 Artist Video

艺术对谈 Dialogue

台北·敦仁 展馆 DunRen Gallery

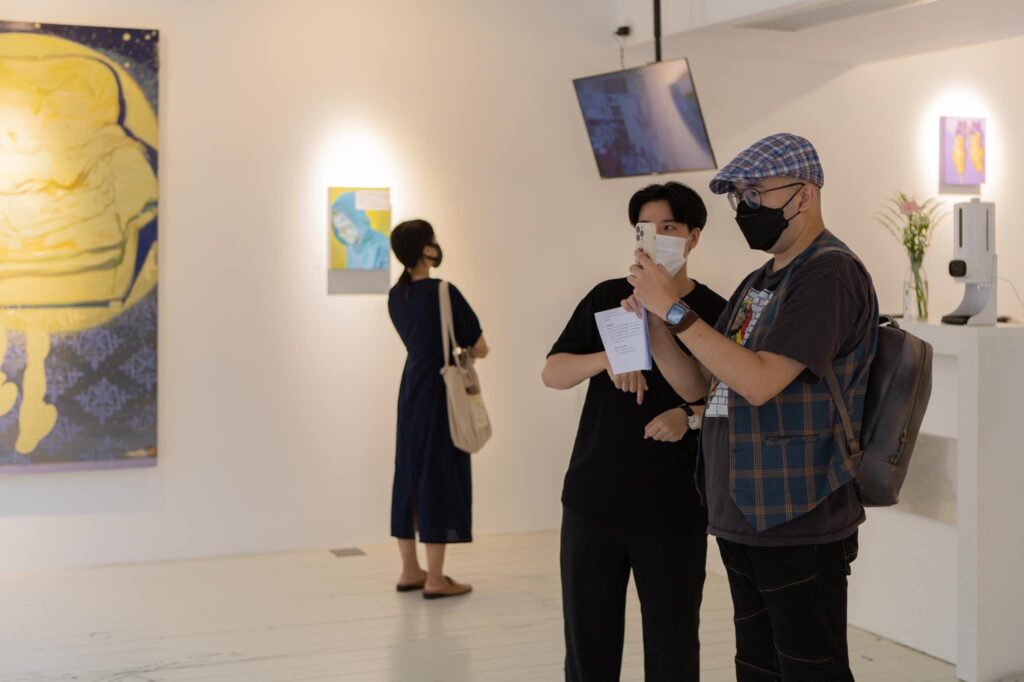

媒体日活动照片

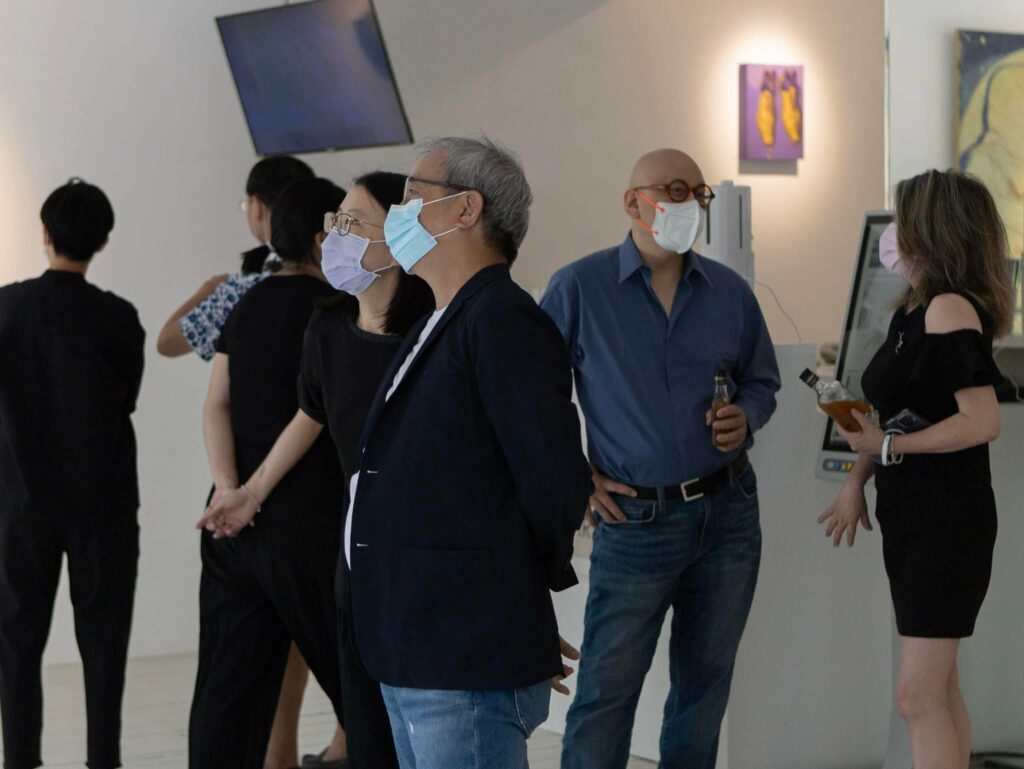

开幕日活动照片

Bluerider ART 台北.敦仁

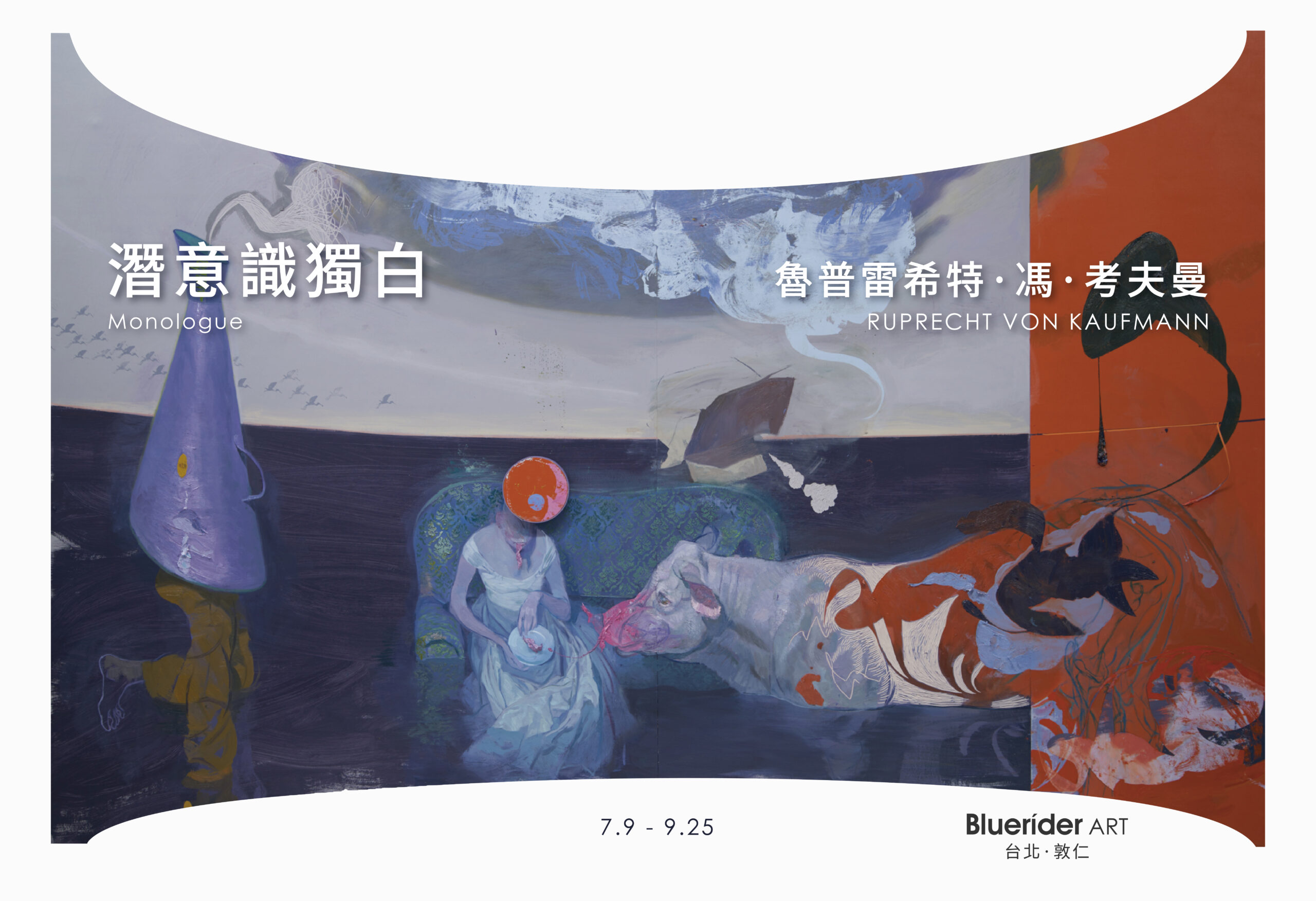

「潜意识独⽩ Monologue」

Ruprecht von Kaufmann鲁普雷希特.冯.考夫曼 在台首个展

鲁普雷希特・冯・考夫曼 Ruprecht von Kaufmann (德,b. 1974) 出生于德国慕尼黑,BFA洛杉矶艺术中心设计学院毕,曾任教柏林艺术大学、汉堡应用科学大学和莱比锡美术学院,现居住创作于柏林。作为一位突出的图像叙事艺术创作者,他选择研究围绕著人的各种层面,利用当代绘画的视觉语言,展现批判叙事与平行现实幻境。于欧洲各大城市伦敦、柏林、斯图加特、奥斯陆、纽约展出;作品获纽约知名收藏家族(Hort Family)、德国 Sammlung Philara 博物馆、德国法兰克福德意志联邦共和国国家银行等,众多公私立机构永久收藏。

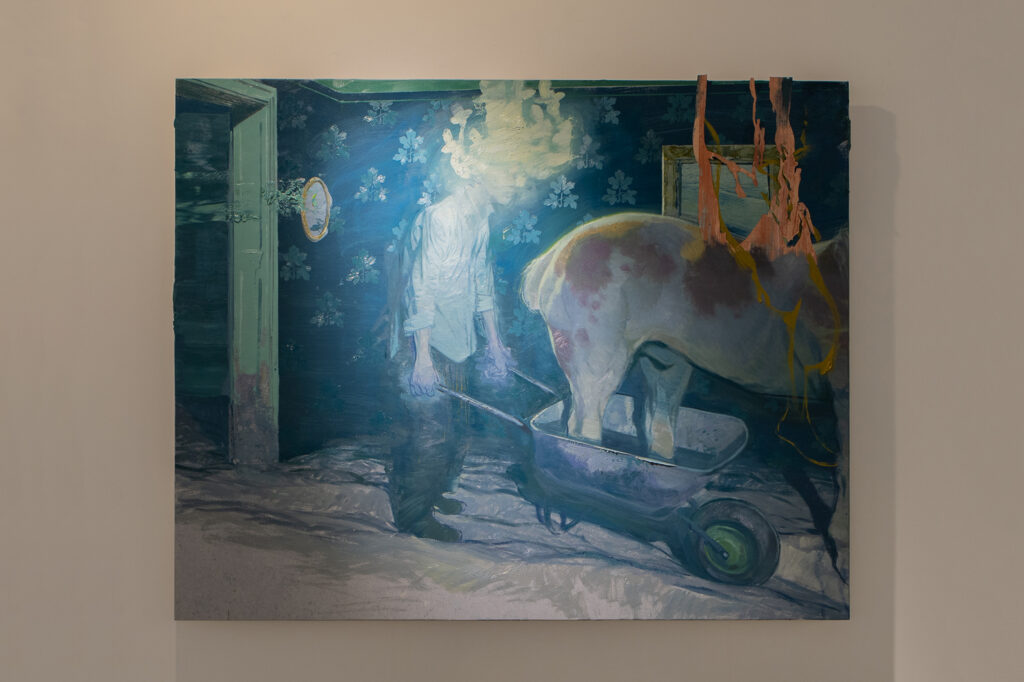

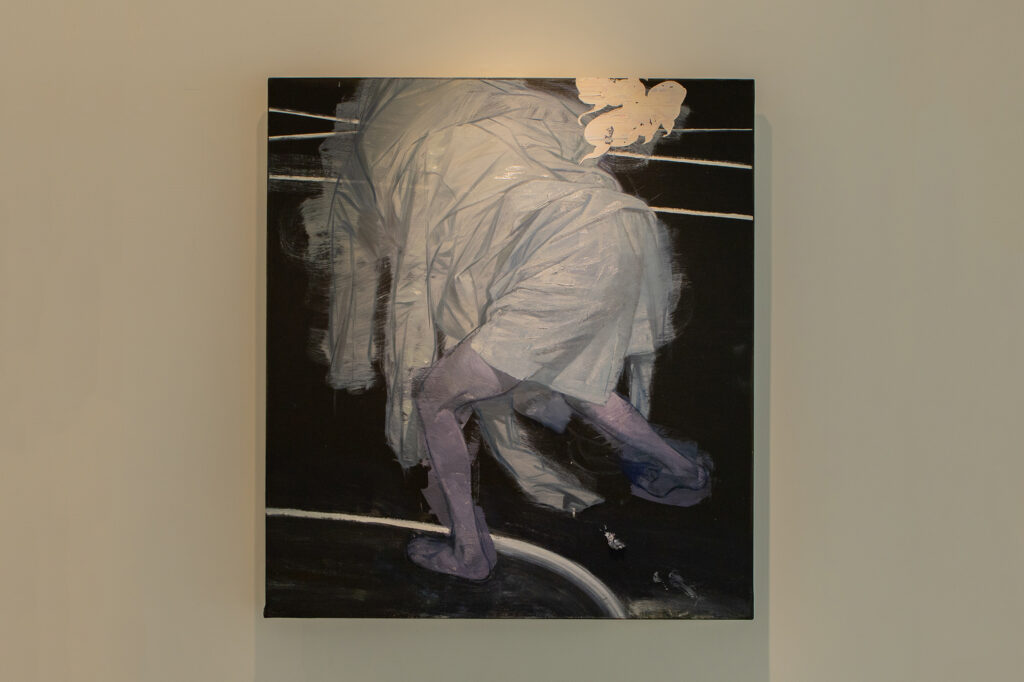

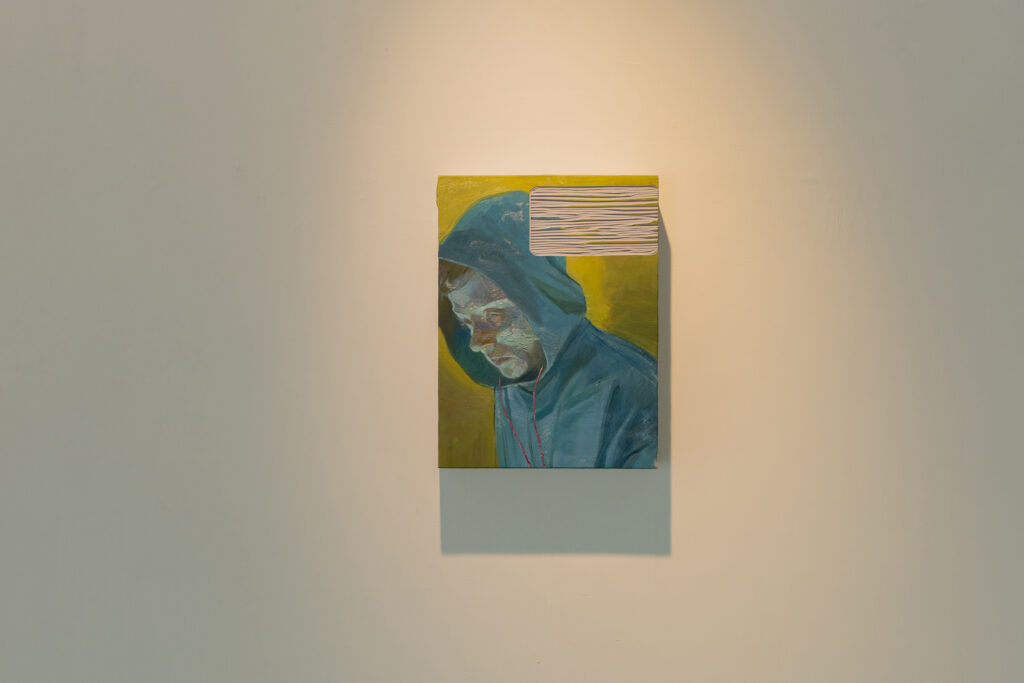

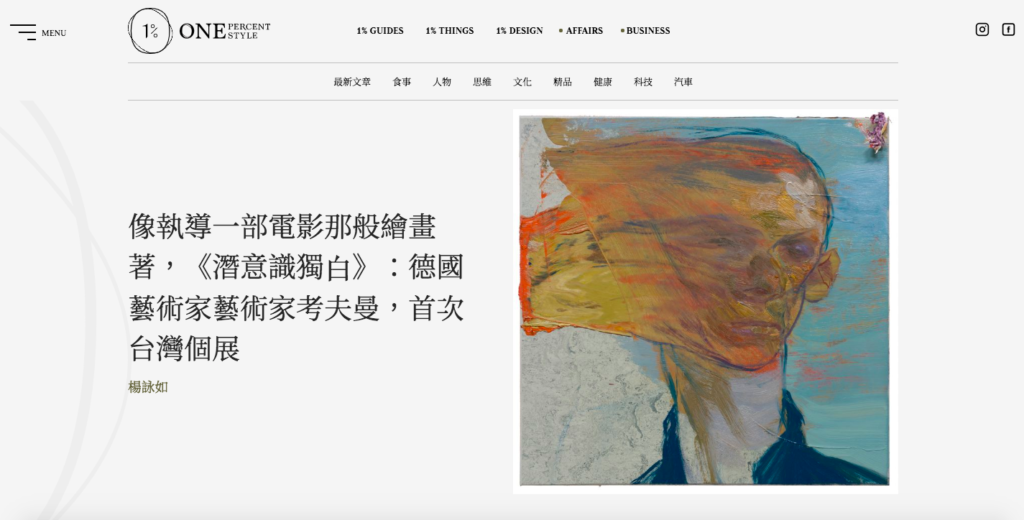

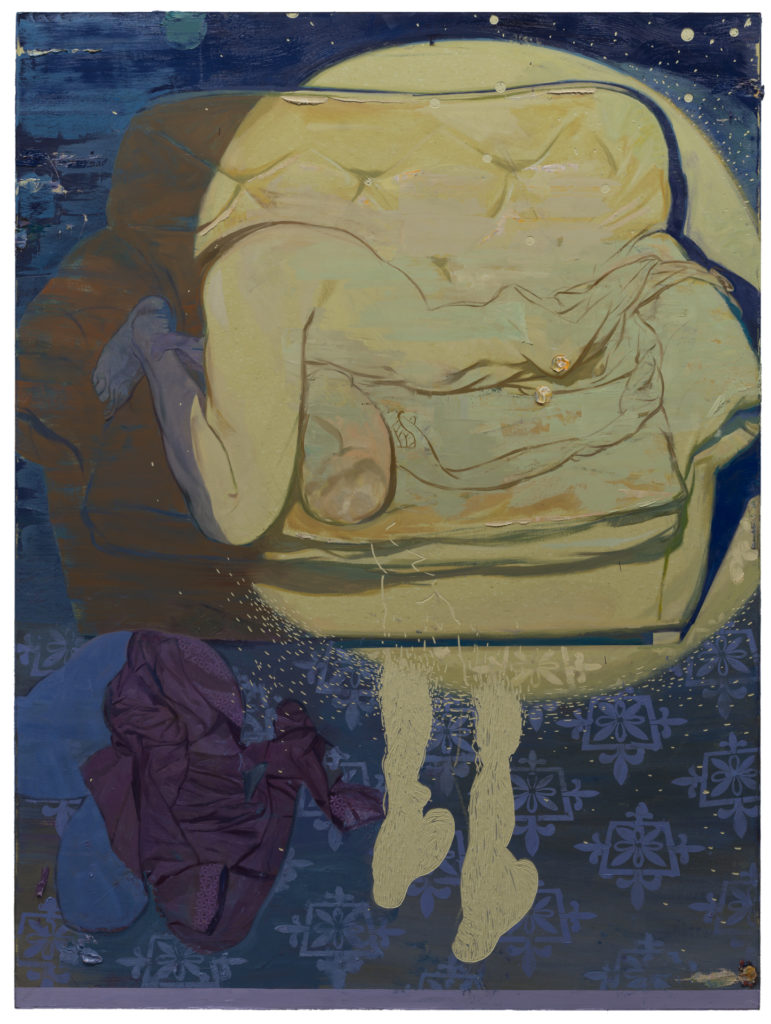

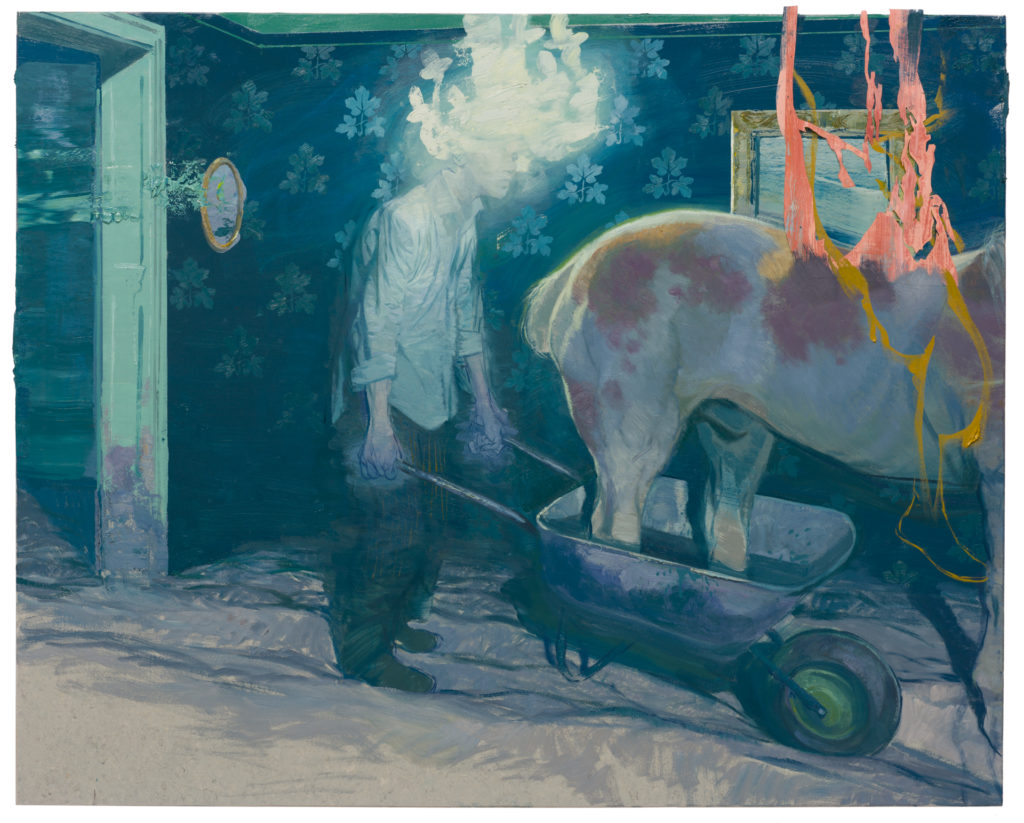

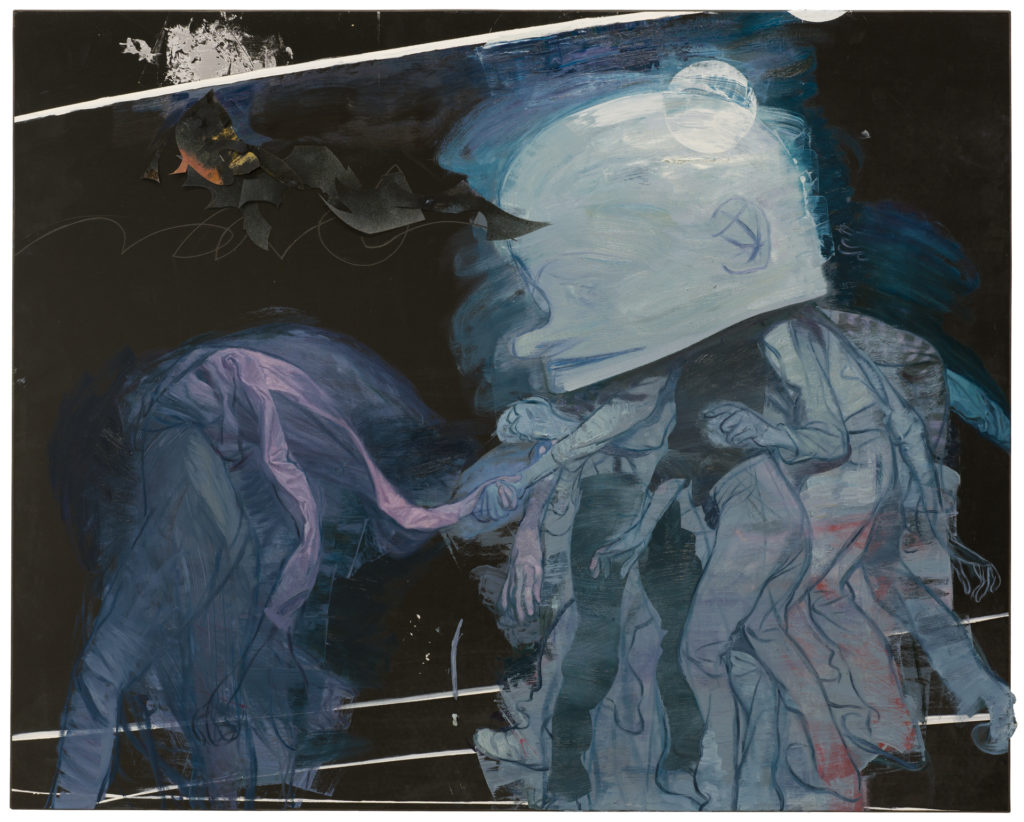

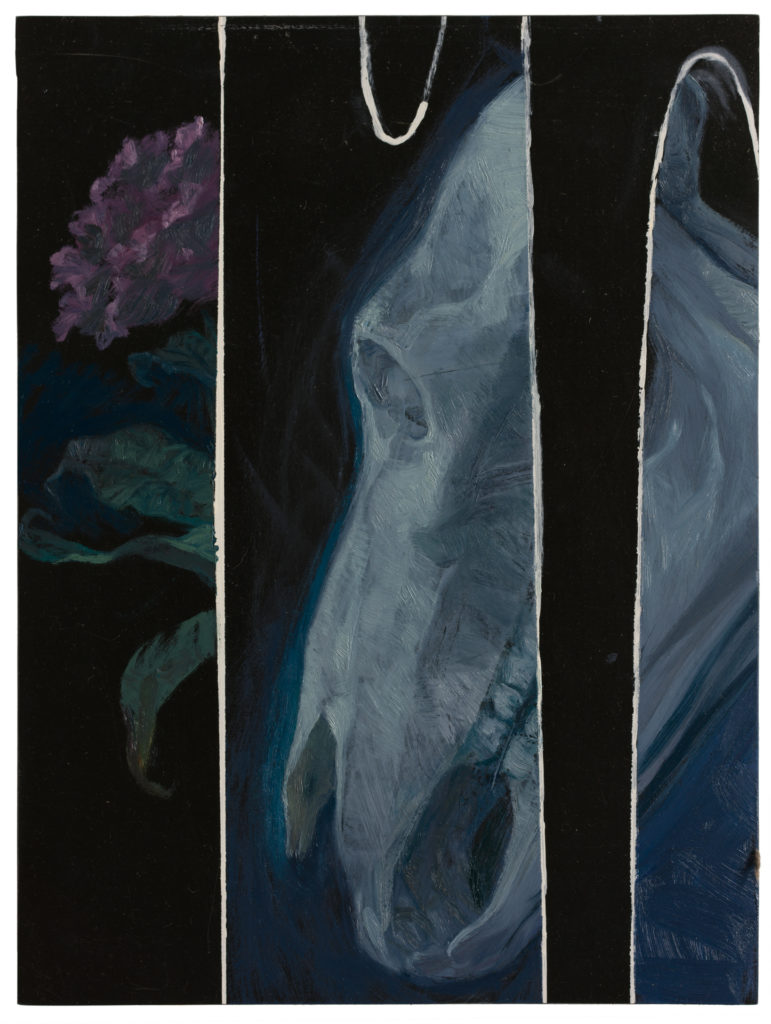

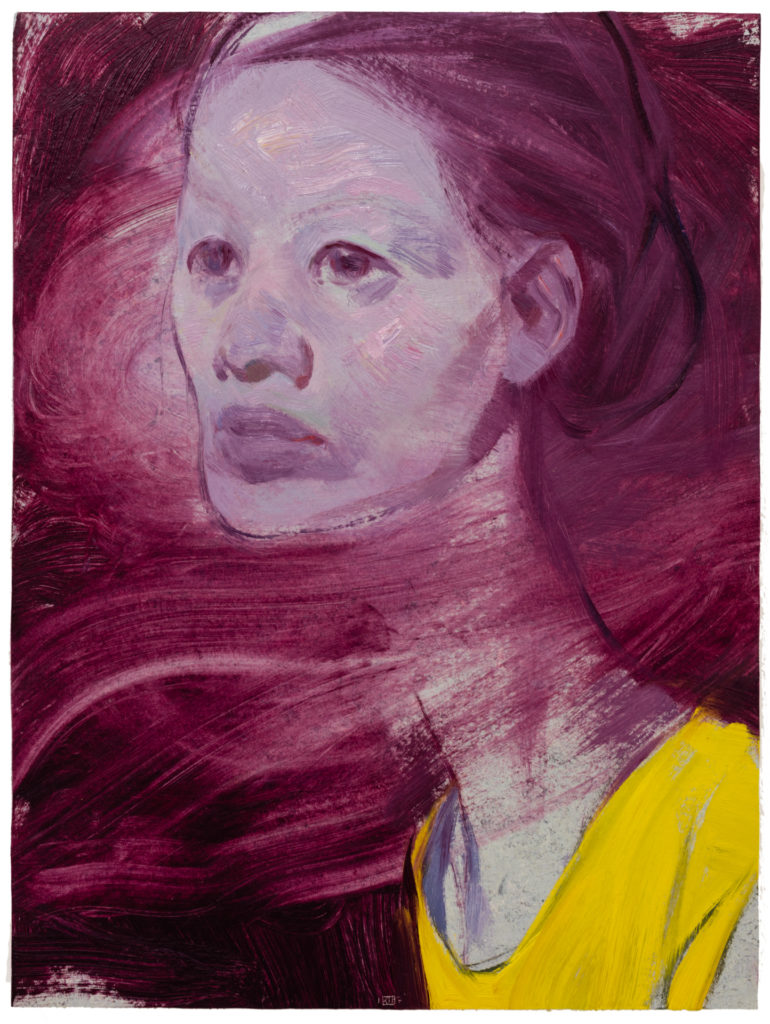

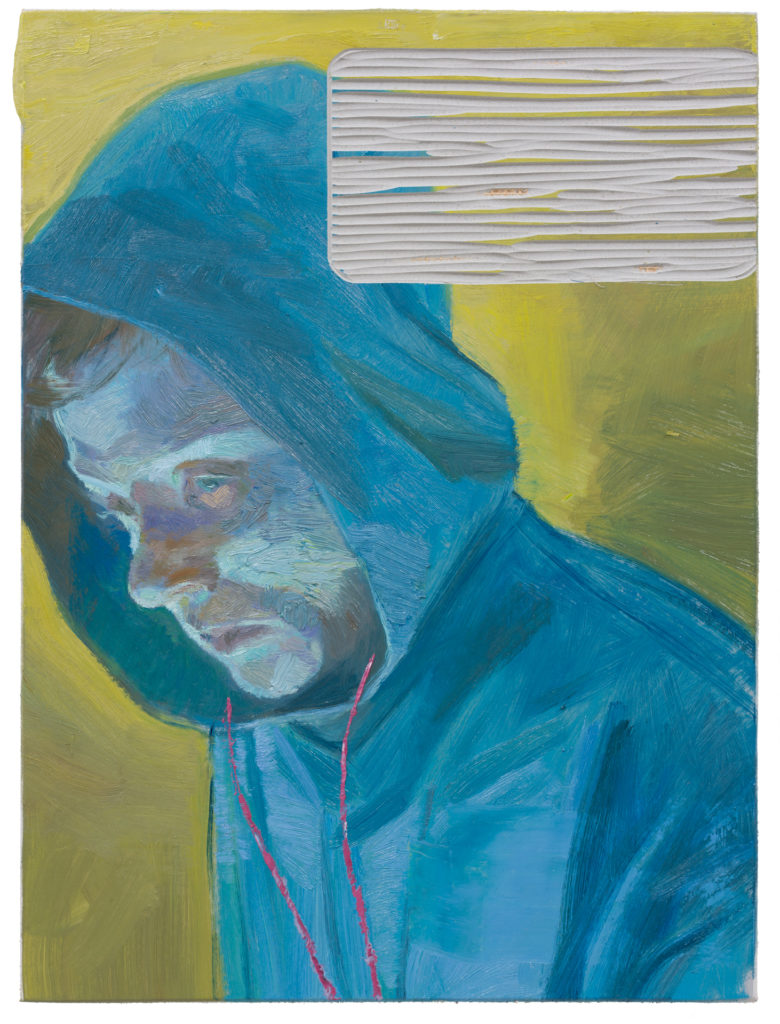

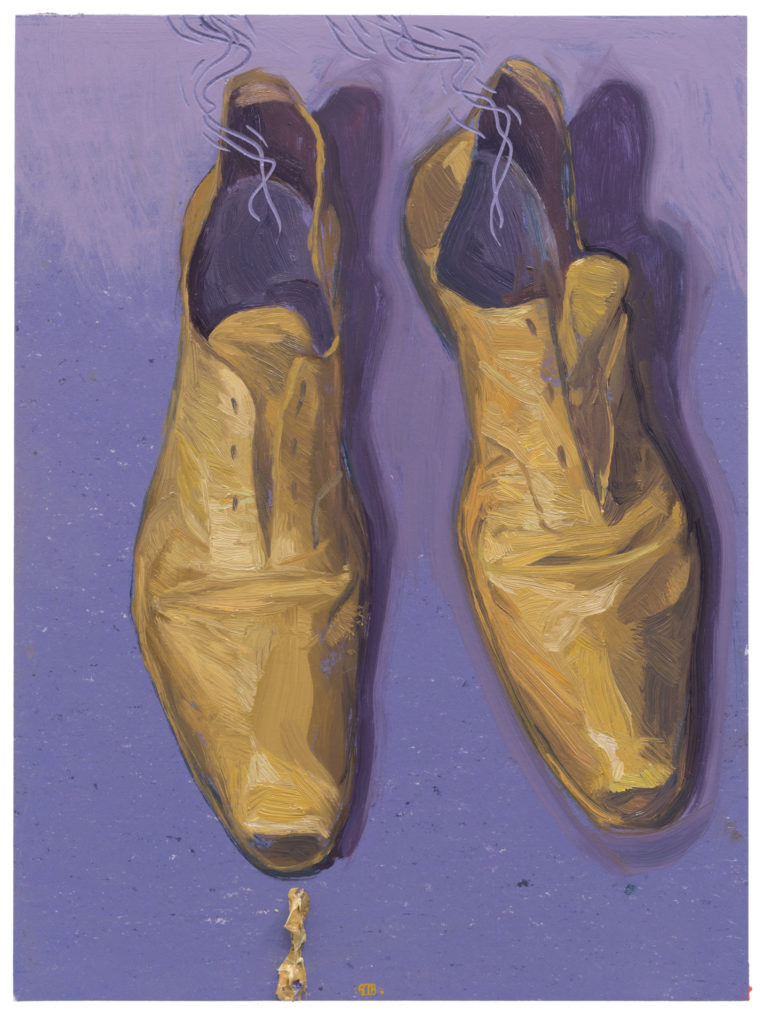

艺术家考夫曼 Kaufmann 使用油彩创作,包括绘画、雕塑和纸上作品,他创作灵感来自于生活经验,更多时候他利用阅读文学、音乐、电影引发脑海中各种意象与想像,尤以电影影响甚钜。相较于电影的时间叙事与声线的交织,绘画是定格的作品,艺术家在绘画中引入前与后的感觉,以此方式打开更多表达的可能性,也预期观者观看作品时,随著画面构图的引导,产生强烈的情绪反应。绘画是连续性的决策所构成的结果,但同时也会承担著不可预期的画面,如在他的作品中常见反覆被厚涂消失、模糊的面孔,指涉未设限且开放的人物形象。虽然考夫曼 Kaufmann 擅长观察与捕捉人的形象,但却不是创作传统的「肖像画」——人的面孔不是指特定的对象,而是特定类型的人。在低彩度、象徵抑鬱色彩的连续性构图,考夫曼 Kaufmann 捕捉到许多深刻的个人时刻、个体的脆弱,也暗示了一种普遍的人类经验。

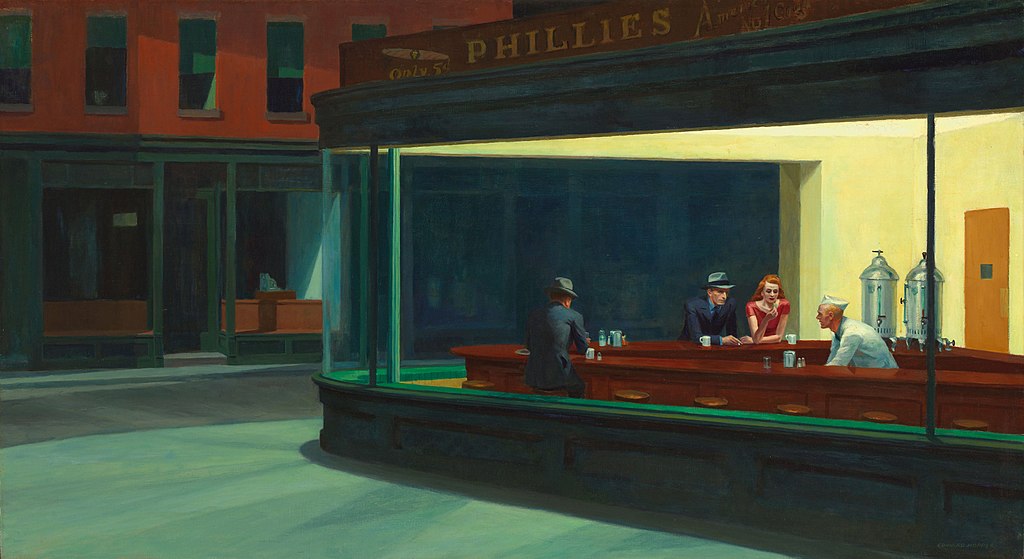

具象艺术(Figurative Art)是指作品的形象以现实世界中的物件为基础,并在各种可辨识的人事物中,带入各种艺术家的观点与思想。不同于人物画经典艺术家法兰⻄斯.培根(Francis Bacon)的作品受希腊古典悲剧的影响,表达人类的残酷暴力与恐惧,人物画抽搐般的面孔特徵,人的形象与空间保持消失、失衡等状态,表现行尸走肉的灵魂。考夫曼 Kaufmann 以内敛且细腻的方式呈现人物画,以开放及幽默的手法,描绘当代人的矛盾与失落,他的创作融合超现实及荒诞不羁,谈论个人的疏离及孤独寂寥。对照1940年代美国艺术家爱德华.霍普(Edward Hopper)的作品描绘各个静谧场景、窗边、加油站、餐馆中的人们,每个独立个体都陷入沉思彼此疏远,这些个体间的关係及世界的想像,引发观者的好奇。或是当代挪威艺术家拉尔斯.艾林(Lars Elling)所描绘的虚实交错的魔幻世界,叠影的画面,是对周围环境世界的不完整体验,憧憧幽影的再现。对应经典文学领域,法国文学家卡缪(Albert Camus)的荒诞,以孤寂与心灵疏离、创造了人们荒谬的现实,人类既无力作恶也无力为善。抑或是当代电影鬼才大卫.林区(David Keith Lynch)的诡异多变的超现实风格,创造如梦似幻的影像。鲁普雷希特.冯.考夫曼 Ruprecht von Kaufmann 以其擅长讲故事,同时作品充满黑色幽默及浓烈的忧鬱色彩的风格,一如其他跨越时代的创作者,他的作品反映出当下我们在动盪不安的社会中的行为、思想和感受。

在历经 Covid-19 流行的这段期间考夫曼 Kaufmann 也表示他感受到社会孤立的压力,这对任何人来说都是艰难的时刻,对应著持续变化的日常风景,在逐渐接近末日的当下,人彷彿在梦境游走,经历一切的超现实。在艺术家鲁普雷希特.冯.考夫曼 Ruprecht von Kaufmann 的世界,人们延续著日常的场景,甦醒、又潜入梦境,在即将崩毁的世界建立秩序,持续向前。

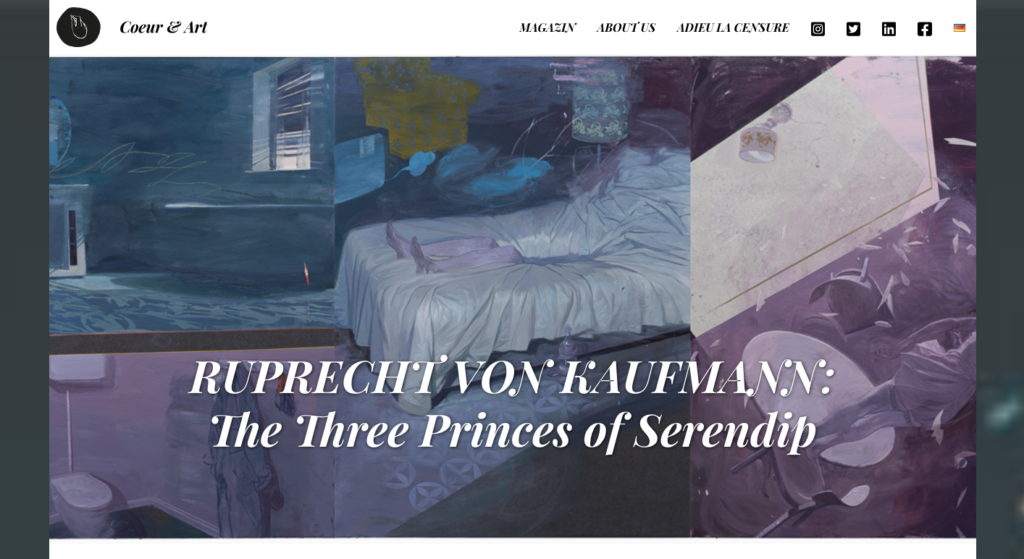

这次在 Bluerider ART 登场的鲁普雷希特.冯.考夫曼 Ruprecht von Kaufmann 个展「潜意识独白 Monologue」,展出跨越创作年代的主题,像大型作品 State of the art (2015)、Precious (2015),参照古典绘画的精緻构图,魔幻写实的物件与人物,展开多则午夜诗篇。或是作品 Es geht weiter (2020)、Die Stadt der Blinden (2020),则描绘在移动、在眼盲状态下集体行动的人群,一场荒谬又充满戏剧性的历险记。并展出多幅描绘人具象脸孔的作品,如 Gone Man (2020)、Young man look at yourself (2020),呈现艺术家与描绘对象者的相遇,模糊的细节回忆起意识洪流中曾经相遇的脸庞。各种电影与文学元素的输入,构图、光线、颜色、裁切输出成为个人创作的灵感,每个角色面对观众独自表述,每一次绘画创作对考夫曼 Kaufmann而言,就如同执导一部电影一般(Painting as if Directing a Movie)。

「潜意识独白 Monologue」- Ruprecht von Kaufmann鲁普雷希特.冯.考夫曼在台首个展

VIP Opening开幕式(藏家预览):7.9 Sat. 2pm – 5pm

Open to public大众开放:7.9 Sat. 5pm – 7pm

展期:2022.7.9 – 9.25

地点:Bluerider ART 台北.敦仁

Tue.-Sun., 10am – 7pm

台北市大安区大安路一段 101 巷 10 号 1F

艺术家 Artist

Ruprecht von Kaufmann

鲁普雷希特・冯・考夫曼

(Germany ,b.1974 )

鲁普雷希特・冯・考夫曼 Ruprecht von Kaufmann (德,b. 1974) 出生于德国慕尼黑,BFA洛杉矶艺术中心设计学院毕,曾任教柏林艺术大学、汉堡应用科学大学和莱比锡美术学院,现居住创作于柏林。作为一位突出的图像叙事艺术创作者,他选择研究围绕著人的各种层面,利用当代绘画的视觉语言,展现批判叙事与平行现实幻境。于欧洲各大城市伦敦、柏林、斯图加特、奥斯陆、纽约展出;作品获纽约知名收藏家族(Hort Family)、德国 Sammlung Philara 博物馆、德国法兰克福德意志联邦共和国国家银行等,众多公私立机构永久收藏。

2019 Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, Germany(德国现代艺术陈列馆)

2019 `Inside the Outside´, UN Headquarters, New York (纽约联合国总部)

2018 `Die Evakuierung des Himmels´, Kunsthalle Erfurt, Erfurt (爱尔福特艺术馆)

2019 “The three princes of serendip” Kunstsammlung Neubrandenburg (新勃兰登堡艺术收藏)

艺术家考夫曼 Kaufmann 使用油彩创作,包括绘画、雕塑和纸上作品,他创作灵感来自于生活经验,更多时候他利用阅读文学、音乐、电影引发脑海中各种意象与想像,尤以电影影响甚钜。相较于电影的时间叙事与声线的交织,绘画是定格的作品,艺术家在绘画中引入前与后的感觉,以此方式打开更多表达的可能性,也预期观者观看作品时,随著画面构图的引导,产生强烈的情绪反应。绘画是连续性的决策所构成的结果,但同时也会承担著不可预期的画面,如在他的作品中常见反覆被厚涂消失、模糊的面孔,指涉未设限且开放的人物形象。虽然考夫曼 Kaufmann 擅长观察与捕捉人的形象,但却不是创作传统的「肖像画」——人的面孔不是指特定的对象,而是特定类型的人。在低彩度、象徵抑鬱色彩的连续性构图,考夫曼 Kaufmann 捕捉到许多深刻的个人时刻、个体的脆弱,也暗示了一种普遍的人类经验。

具象艺术(Figurative Art)是指作品的形象以现实世界中的物件为基础,并在各种可辨识的人事物中,带入各种艺术家的观点与思想。不同于人物画经典艺术家法兰⻄斯.培根(Francis Bacon)的作品受希腊古典悲剧的影响,表达人类的残酷暴力与恐惧,人物画抽搐般的面孔特徵,人的形象与空间保持消失、失衡等状态,表现行尸走肉的灵魂。考夫曼 Kaufmann 以内敛且细腻的方式呈现人物画,以开放及幽默的手法,描绘当代人的矛盾与失落,他的创作融合超现实及荒诞不羁,谈论个人的疏离及孤独寂寥。对照1940年代美国艺术家爱德华.霍普(Edward Hopper)的作品描绘各个静谧场景、窗边、加油站、餐馆中的人们,每个独立个体都陷入沉思彼此疏远,这些个体间的关係及世界的想像,引发观者的好奇。或是当代挪威艺术家拉尔斯.艾林(Lars Elling)所描绘的虚实交错的魔幻世界,叠影的画面,是对周围环境世界的不完整体验,憧憧幽影的再现。对应经典文学领域,法国文学家卡缪(Albert Camus)的荒诞,以孤寂与心灵疏离、创造了人们荒谬的现实,人类既无力作恶也无力为善。抑或是当代电影鬼才大卫.林区(David Keith Lynch)的诡异多变的超现实风格,创造如梦似幻的影像。鲁普雷希特.冯.考夫曼 Ruprecht von Kaufmann 以其擅长讲故事,同时作品充满黑色幽默及浓烈的忧鬱色彩的风格,一如其他跨越时代的创作者,他的作品反映出当下我们在动盪不安的社会中的行为、思想和感受。

在历经 Covid-19 流行的这段期间考夫曼 Kaufmann 也表示他感受到社会孤立的压力,这对任何人来说都是艰难的时刻,对应著持续变化的日常风景,在逐渐接近末日的当下,人彷彿在梦境游走,经历一切的超现实。在艺术家鲁普雷希特.冯.考夫曼 Ruprecht von Kaufmann 的世界,人们延续著日常的场景,甦醒、又潜入梦境,在即将崩毁的世界建立秩序,持续向前。

Press

台北·敦仁 作品 Works

訪談文章及學術評論 Art Critique

图像形成如一面(扭曲的)现实之镜

By Dr. Sylvia Dominique Volz

人类存在的所有复杂性—那种透过操纵来控制他人的努力,一种无关乎理性或非理性的原始本能行为—是Ruprecht von Kaufmann作品的主轴。在这里,人类因为其世俗存在中的需求、脆弱、与有限性,被大自然与自身物种视为是一种威胁。

既深沉又神秘地,这些画作吸引着观众并使他们着迷。我们受到作品的加密与相互矛盾性质所带来的多样性与复杂性挑战。它们释放了我们内心的各种联想,从而产生了一种混合的情绪;正如同艺术家所指出的,这些情绪与我们自己的生活经验最密切相关:从焦虑不安、沮丧、与感觉到受威胁,到喜悦、爱、与希望—而且有时候混合这所有情绪于一张画作之中。我们试图参与、破译、和理解事物,最终得出结论发现这所发生的一切不全是在眼前,更多的是发生在我们自身上面。这些画作主角是反映出我们自己吗?我们扮演着什么角色?我们是否参与于展开的画作前并将其意念延伸成为自我的一部份呢?

因此,这些成为与身为观者的我们产生共鸣与互动的图像。在社交媒体的世代,这对我们来说似乎很自然。Ruprecht von Kaufmann本人着迷地观察着所谓的用户如何利用叙述来塑造他们自己的个人特质。这些即是被操控的主观真相,因为有些图像的设计确实旨在向外传达意念。观看的时候,脑中所感知到的是情感上触动观者的一幅美丽(被美化的)肖像,因为它产生了一种匮乏感且唤醒了深沉的隐性需求。简而言之,Ruprecht von Kaufmann艺术地捕捉了现实与虚构之间的差异。在他一幅描绘一位背对着的女性正在脱去她比例匀称的皮肤的画作中,显现出来的是一位瘦到近乎消失的纤弱人形,而且她与即将要被抛掉的皮肤形象几乎没有任何共同之处(Take off Your Skin[译:脱去你的外皮]。(Take off Your Skin[譯:脫去你的外皮])。

然而,人们套用各种角色或扮演操控形象这种行为,不仅是现代现象,而是或多或少地贯穿了整个人类与艺术史;人类始终在乎着他们想成为什么样的人以及他们想要被看到的角色。即便是在古代,人或表面形象的概念也普遍地被演员应用于所使用的面具以及其于生活中或戏剧中所扮演的角色。几个世纪以来,肖像,不论是文字还是图像,从轮廓到每个小细节都经常被精心设计着:想想那些以精心部署的象征手法来炫耀自己社会地位、教育程度、以及所谓高尚特质的统治者们,从而以最真实的意义建构了他们的形象。

Ruprecht von Kaufmann对于在真实与虚构世界之间摇摆不定的形象特别感兴趣;因此,对于美国创作歌手 Tom Waits所写的歌词成为他的灵感来源之一也就不足以为奇了—这位音乐家本身就是一位难以自我受限的创作家,他以在歌词中呈现各种虚构人物并营造出一种不一致且复杂的氛围为特色,如同我们在Ruprecht von Kaufmann的作品中所感受到的那般。画作中的主角以不同的形式出现,有些带有强烈的操控或威吓感,有些则是有需求或脆弱的感觉。我们会遇上一些奇特的混合型生物,例如半人马这种怪物睡在床上,然后一位裸体的女性信任地依偎在它身上(Monster [译:怪物]),或者是一个完全被包裹在像麻布袋中的生物蹒跚地在房间内移动着(Die Gefährten [译:伙伴们])。他们的真正身份其实并未向我们揭露,尤其因为他们的头被转向、被扭曲得面目全非、或者被遗漏了。由于我们总是试图阅读与识别脸部特色以定位我们与对方之间的关系,这样的呈现更是让人感到困惑。(Monster [譯:怪物]),或者是一個完全被包裏在像麻布袋中的生物蹣跚地在房間內移動著(Die Gefährten [譯:夥伴們])。他們的真正身份其實並未向我們揭露,尤其因為他們的頭被轉向、被扭曲得面目全非、或者被遺漏了。由於我們總是試圖閱讀與識別臉部特色以定位我們與對方之間的關係,這樣的呈現更是讓人感到困惑。

基于明显受到人们与其行为控制的因素,当观察那些有时显得复杂的图像空间时,我们容易疏忽地断言Ruprecht von Kaufmann的作品缺乏叙述性。事实上,这并非艺术家本意:在他看来,叙事是触动人们情感的基本手法。因此,他不愿意单纯地从形式或知识层面上接触绘画。这确实值得注意,因为这使他的画作与当前艺术语境对绘画叙事的消极态度相悖。此外,这种立场十分有趣,因为Ruprecht von Kaufmann让人对他的印象是拥有高智商的人,而且他的画作更是证明他对历史、文学、古代神话与音乐有着深入的研究。

尽管如此,在观众眼前展开的一切无论如何都不能被视为一个完全发展的故事。相反的是,它们是片段,或者更确切地说,它们是带有暗示意味但不是解答的叙述线索。一开始,艺术家使用符合我们既定观看模式与主观经验视野的有形手法来唤起叙事,因而提供了一种看似简单的方式进入图像。这种手法同样适用于马戏团场景、山景、或例如童年或成年过渡时期的自传主题等应用。

随后,我们便会对自我假定的见解产生怀疑。Ruprecht von Kaufmann便向我们展示各种难以理解的细节,像是一匹有两个后驱的马(Pastorale [译:牧人]),一个不合建构逻辑的空间结构,或者甚至是图像中的间隙;当独自观赏时,不只无助于理清情境,反而延伸出更多的疑问。观众更是被鼓励自由发挥幻想、解决矛盾之处、并化不合逻辑为合理。Ruprecht von Kaufmann表示:“图像实际上只在观众自己的脑海里出现。”叙事片段因此扮演着艺术家为我们搭建的桥梁角色,而他本人则在基地周遭徘徊,并且在鼓励我们持续前进之后撒退。(Pastorale [譯:牧人]),一個不合建構邏輯的空間結構,或者甚至是圖像中的間隙;當獨自觀賞時,不只無助於釐清情境,反而延伸出更多的疑問。觀眾更是被鼓勵自由發揮幻想、解決矛盾之處、並化不合邏輯為合理。Ruprecht von Kaufmann表示:「圖像實際上只在觀眾自己的腦海裡出現。」敘事片段因此扮演著藝術家為我們搭建的橋樑角色,而他本人則在基地周遭徘徊,並且在鼓勵我們持續前進之後。

另一个Ruprecht von Kaufmann的作品与纯粹叙事性质背道而驰的方面是他在开始工作之前并不会准备一套填满细节的概念。他从一个模糊的想法开始行动,允许这些想法引导他。最后在绘画的过程当中,整体的作品细节才会逐渐变得清晰。

艺术家本人喜欢提及“偶然性”原则,意即偶然观察到一些原本无意探寻的事物,却展开新的惊喜发现。这种原则反映在Ruprecht von Kaufmann的创作艺术过程之中,使他不需考虑整体的概念,能够自由地从一个灵感进行到下一个想法。偶然的连结从这里或那里突然冒出、或者产生改变方向的想法,而这些有时会带来意想不到的发现。最后的结果可能是钻孔或拼贴状的元素,破坏作品的表面使其产生动态感。

画作的标题通常也是在创作过程中才确定。如果,以例外的情况来说,假设作品主题在一开始就设定好,它将会是参考启发艺术家灵感的一句名言、声明、或者歌名—例如Babe I’m Gonna Leave You (译:宝贝,我要离开你了)或You never know (译:你从不知道)。然而,随后在图像表面上所形成的东西将会与纯粹的示意图相去甚远。Babe I’m Gonna Leave You (譯:寶貝,我要離開你了)或You never know (譯:你從不知道)。然而,隨後在圖像表面上所形成的東西將會與純粹的示意圖相去甚遠。

整体来说,这些标题在某种程度上常常具有令人惊讶的讽刺意味—例如,在My Thoughts Grow so Large on Me (2016) (译:思想在我身上变得如此之大)的作品中,画作主角的头顶上却几乎只剩下抹刀涂抹的残留漆料;这让人联想到的反而是废物而非其他情操更高尚的活动。或者例如Der Entertainer (译:表演者)中,主角的头部仅以一缕轻烟呈现。又或者当Rude Awakening (译:后悔莫及)里面熟睡的情侣从向下倾斜的床上倒挂下来时,仿佛真的被丢弃了一样。不证自明地,一个幽默的标题能够相对化作品的阴郁与沉重;就如同当那只像是地狱猎犬一样的生物正在撕毁另一只野兽时,画作的标题却是Sorglos (译:无忧无虑)。如此这般地产生吸引人的对比性,使人联想起Martin Scorsese或Quentin Tarantino所执导的电影中,残忍行径的场景通常会伴随着欢快的配乐。My Thoughts Grow so Large on Me (2016) (譯:思想在我身上變得如此之大)的作品中,畫作主角的頭頂上卻幾乎只剩下抹刀塗抹的殘留漆料;這讓人聯想到的反而是廢物而非其他情操更高尚的活動。或者例如Der Entertainer (譯:表演者)中,主角的頭部僅以一縷輕煙呈現。又或者當Rude Awakening (譯:後悔莫及,第138頁)裡面熟睡的情侶從向下傾斜的床上倒掛下來時,彷彿真的被丟棄了一樣。不證自明地,一個幽默的標題能夠相對化作品的陰鬱與沉重;就如同當那隻像是地獄獵犬一樣的生物正在撕毀另一隻野獸時,畫作的標題卻是Sorglos (譯:無憂無慮)。如此這般地產生吸引人的對比性,使人聯想起Martin Scorsese或Quentin Tarantino所執導的電影中,殘忍行徑的場景通常會伴隨著歡快的配樂。

Ruprecht von Kaufmann的作画手法玩弄着我们典型的感知方式,使观者的双眼不停移动着。我们的双眼找寻支点,然后在找到了之后再次分心;接着可能再次返回稍早停伫过的点,然后再离开朝向其他方向。物理上来说,在画作前的空间上下移动着似乎仍然无法提供足够的说明。可能的例子是In the House (译:房子里)这个作品,观者在作品中的视线移动—如电影运镜那般—由左至右穿过一个屋子。整个过程经历了六个位置,从楼梯井开始,观众被引导至越来越深的内部,直到突然发现自己身处屋外。In the House (譯:房子裡)這個作品,觀者在作品中的視線移動—如電影運鏡那般—由左至右穿過一個屋子。整個過程經歷了六個位置,從樓梯井開始,觀眾被引導至越來越深的內部,直到突然發現自己身處屋外。

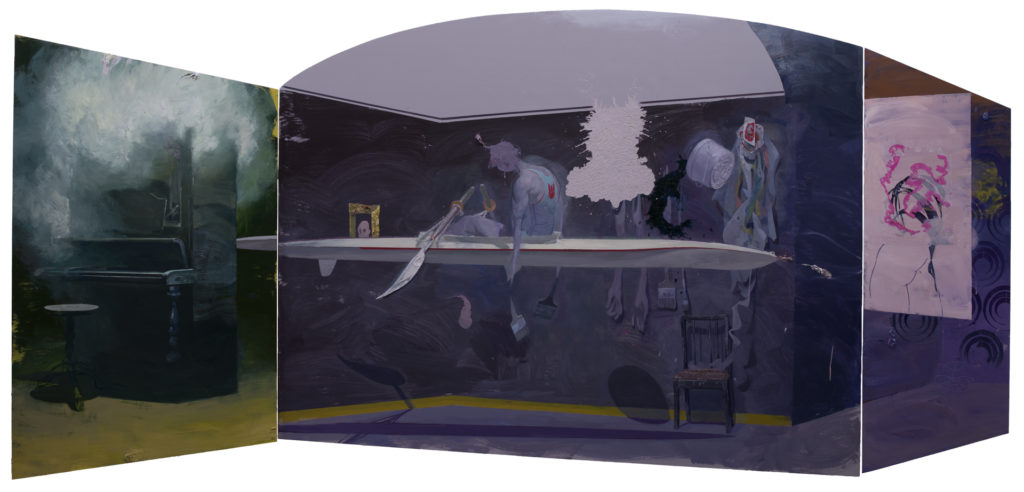

对Ruprecht von Kaufmann而言,重要的是视角的变化;这个概念在这里特别容易理解,因为艺术家分别在鸟瞰方式与采用较观者视线稍高一些的视角之间交替变化着,一次从左斜对角,然后下个瞬间便改由右斜对角开始。眼神的闪烁扫视为观者带来一种不安全感,甚至是一种令人压抑的感觉—特别是当艺术家从背后的角度向我们展示一位杂耍演员,站在令人眼花缭乱的高空秋千上俯视着马戏团的地板,那是最专注且神经紧绷的时刻。那感觉几乎像是地板正在从我们的脚下被抽出 — 好像我们才是负责要像杂耍演员那般地荡那个秋千并在空中旋转(Der Trapezakt (译:高空秋千))。在State of the Art (译:先进前卫的)这种多重元素作品中,其绘画的视角与绘板的形状让我们产生更多的问题,像是一幅可折叠的祭坛画,却有着不对称的外形,让人永远无法如愿地使其发挥作用。(Der Trapezakt (譯:高空鞦韆)。在State of the Art (譯:先進前衛的,第58頁)這種多重元素作品中,其繪畫的視角與繪板的形狀讓我們產生更多的問題,像是一幅可折疊的祭壇畫,卻有著不對稱的外形,讓人永遠無法如願地使其發揮作用。

虽然Ruprecht von Kaufmann多年来一直在画布上以油彩创作,2014成为了一个转折点,他决定使用油毡作为画布,并从那时起一直这样创作着。多部组成的肖像作品Die Zuschauer (2014) (译:观众们)就是这种转换的例子:从55张DIN A4尺寸的画作中凝视着我们的,是各种人像或“人格特质”;这里运用的是各种形式的肖像画技,从头像到及胸半身像,再到头肩像至完整的半身像。当你移动视线进入时,你会注意到有些肖像似乎时不时会消失。眼睛部位被挖空、仅以模糊或勾勒的方式呈现脸部特征、或者是直接以刮刀涂抹并因此可能使其他部份受损。同样引人注目的是我们看到的各式色彩,这种用色风格从保守的灰与蓝色调变化到尖锐的橙色、黄色、或明亮的洋红色。然而,这样的色彩试验不只与肖像本身有关,也似乎是从背景色调中汲取灵感。有时候,油毡上仍然明显留有奇怪的色调。

在这里,我们会发现自己处于色彩的核心来源:实际上是油毡本身真正地为画作定下了基调。Ruprecht von Kaufmann偶然发现了这种材料—一种亚麻籽油与软木的混合物。当他在家中建构作品时,他发现各种颜色的油毡板,而这很快地引发了他的艺术好奇心。这种材料以各种色调生产,有望成为具有无限可能性的实验场域。

他随后订制了一个40 x 30 公分的混色板,并大量地测试油画颜料在画板表面的表现方式;与一般画布不同的是,因为其材料特性的关系,作画时并不需要涂底漆。Ruprecht von Kaufmann也注意到,通常空白的白色补片在画布上总是看起来像“未完成品”,但油毡板的基材在需要时,可以简单地将其“单独放置”(Schmelzwasser (译:融水))。因此,他让自己被各种材料色彩引导着,以各自的色调活力作为参考点。因此,一个有趣的过程、一种对话随之开启,因为每一个图像与每种色调都将产生新的想法:当紫罗兰色遇上黄色、黄色碰上蓝色、橙色遇见灰绿色、而洋红色撞入黑色。更具实验性的是这些画作,壁纸或地板上被覆盖满五颜六色的图像,人物则像是身在丛林中那般被框住,例如Monster (译:怪物)、Auferstehung (译:复苏)、Der Zeuge (译:目击者)、或You Never Know (译:你从不知道)。潜在的色彩组合似乎无穷无尽。(Schmelzwasser (譯:融水)。因此,他讓自己被各種材料色彩引導著,以各自的色調活力作為參考點。因此,一個有趣的過程、一種對話隨之開啟,因為每一個圖像與每種色調都將產生新的想法:當紫羅蘭色遇上黃色、黃色碰上藍色、橙色遇見灰綠色、而洋紅色撞入黑色。更具實驗性的是這些畫作,壁紙或地板上被覆蓋滿五顏六色的圖像,人物則像是身在叢林中那般被框住,例如Monster (譯:怪物)、Auferstehung (譯:復甦)、Der Zeuge (譯:目擊者)、或You Never Know (譯:你從不知道)。潛在的色彩組合似乎無窮無盡。

这种新发现的材料符合Ruprecht von Kaufmann长期以来抱持着的渴望,希望更有力量地运用色彩作为单一元素;相较之下,他早期作品的特点是相当均匀柔和的调性。因此,这些图像达到了明显的存在感,但仍能保持足够的隐晦性而不至于太过抢眼。

从画布切换到油毡时,Ruprecht von Kaufmann还因此能实现另一个愿望,即赋予画作中的各个元素更多的图像品质,从而将它们与画作中的其他区域切割开来。如果我们看诸如Schmelzwasser (译:融水)这一类的作品,画中的主角看起来既精致又含蓄,如同画在纸上那般。艺术家尤其喜欢强调笔刷与漆料在油毡上极佳的流动性,非常适合书法手法。他幽默地表示,图像背景可以“像一幅拙劣的油画那般轻松地涂抹”,将颜色保留在最上方,覆盖着下方的漆料。Schmelzwasser (譯:融水)這一類的作品,畫中的主角看起來既精緻又含蓄,如同畫在紙上那般。藝術家尤其喜歡強調筆刷與漆料在油氈上極佳的流動性,非常適合書法手法。他幽默地表示,圖像背景可以「像一幅拙劣的油畫那般輕鬆地塗抹」,將顏色保留在最上方,覆蓋著下方的漆料。

他进一步解释,最后,但同样重要的是,与画布相比,这种材料的特点是抗压性比较高;当Ruprecht von Kaufmann偶尔需要以抹刀在个别部位涂上颜料时,这个特质对他来说相当重要。

更不用说,上述所提及的形式变化也会在对作品内容产生影响。图像元素与背景中未上漆的各个区域有时都会使画作产生一定程度的抽象性,从而与作品的其余部份发展出令人兴奋的对话交流。如果有人看过Ruprecht von Kaufmann在改成油毡板之前的最后一些画布作品—马戏团系列作品—将会发现这其中已经有更抽象化的趋势了。与早期的画作相比,这里的背景已经不再那么精细,但仔细观察的话,更容易让人联想到素描般的几何图形。

最终,这样的发展导向了油毡画,使其中的各个图层都显得更加的鲜明,比以往更清晰—以图像元素、以溶入挖空记号的区块、还有以拼贴方式应用的箔片碎片呈现。所有的这些都有助于提升画作上逐渐增加的雕塑品质—几乎是想挑战古典艺术在绘画、雕塑、与素描流派间的历史区别。

内容层面上,各个图层亦同样表现着不同的含义:举例来说,Schmelzwasser (译:融水)前景出现的四个人像是直接涂在“原始”的油毡板上,代表着四个世代的艺术家族。由左到右,坐着的是Ruprecht von Kaufmann的曾祖父,站在一旁的是他的祖父,接着是在画作斜对角的父亲,以及最后是艺术家本人以几乎水平的方式呈现在作品中。身穿军服的人物以顺时针的方向排列,就像是在暗指时间因素且一切因此顷刻即逝。Schmelzwasser (譯:融水)前景出現的四個人像是直接塗在「原始」的油氈板上,代表著四個世代的藝術家族。由左到右,坐著的是Ruprecht von Kaufmann的曾祖父,站在一旁的是他的祖父,接著是在畫作斜對角的父親,以及最後是藝術家本人以幾乎水平的方式呈現在作品中。身穿軍服的人物以順時針的方向排列,就像是在暗指時間因素且一切因此頃刻即逝。

有趣的是,代表Ruprecht von Kaufmann的人像是画作中唯一仅以轮廓方式呈现的,因此避开了我们的感知;也就是说,他的祖先们享有较大的身体存在。这似乎暗示着他的生活仍然有被“充实”的空间。另外,在人物背后升起的是让人印象深刻的山脉,其中间的部份,现在则是融掉的冰川,已经被从图像表面凿除并破坏掉了。

从他们的穿着来看,图中的人物不只是家人,而且是四代的高山部队。完成山地救援兵役的Ruprecht von Kaufmann强调那段时间培养了他对大自然的热爱。他对大自然有永久的责任感,以及对所有与此相关或者其未来所有世代有责任,这尤其体现在他整个作品反复出现的山地主题之中。这里是向往与纪念相互结合之地—尤其是后者,当艺术家想表达冰川融化的威胁时,不只在上述提及的Schmelzwasser (译:融水)作品,而且也出现在Jannu、Der Fjord (译:峡湾)、Natur (译:自然)、以及Landschaft (译:风景)这些作品之中。特别是当前关于气候行动的辩论与为气候罢课运动正盛行的情况下,这些图像比以往任何时候都更引人注目。Schmelzwasser (譯:融水)作品,而且也出現在Jannu (第185頁)、Der Fjord (譯:峽灣)、Natur (譯:自然)、以及Landschaft (譯:風景)這些作品之中。特別是當前關於氣候行動的辯論與為氣候罷課運動正盛行的情況下,這些圖像比以往任何時候都更引人注目。

很明显的,Ruprecht von Kaufmann的画作永远不应该单纯地以主观自传为背景下去思考,然而,更甚于此的是,我们必须以全世界通用普遍有效的角度来思考这些作品。这些是极度个人化的画作,我们只能从自己的情绪之中来理解。我们从中寻找、认识、质疑所呈现的内容并进一步将其发展。画作主角的力量或无力都反映且感动着我们,主要是因为它们展现了人类多么地易变,无论是消极还是积极的层面上。从肇事者转化成受害者的步骤—或反之亦然—往往是一步之遥;而在这种独特的纠缠之中,我们彼此相互影响着。在Ruprecht von Kaufmann的画作之中,人的多样性就如同黑白色调之间那般多变。身为观众,我们面临着进入对话的挑战,以便为了透过动态可变的方式实现夙愿。

作者:Sylvia Dominique Volz

为德国著名艺术顾问、编辑和策展人,于海德堡大学取得艺术史博士学位。她为私人藏家及企业机构提供当代艺术收藏顾问谘询,同时也多次担任知名当代艺术私人收藏指南《BMW艺术指南》(The BMW Art Guide)主编。

IMAGE FORMATION AS A (DISTORTING) MIRROR OF REALITY

By Dr. Sylvia Dominique Volz

Human existence in all its complexities—the efforts to control others through mani- pulation, a primal instinctive behavior that does not differentiate between rational and irrational—is the central theme of Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s work. Here, man is seen as a threat to nature and his own species, characterized by the neediness, vulnerability, and finitude of his earthly existence.

Deep and mysterious, the paintings draw viewers in, leaving them spellbound. We are challenged by the diversity and complexity of their encrypted and contradictory nature. They unleash a variety of associations within us, thereby generating a mix of emotions that, as the artist notes, corresponds most closely to our own experiences in life: from unease, dismay, and feeling threatened, to joy, love, and hope—at times all within a single image. We attempt to engage in, decode, and make sense of things, finally to conclude that what takes place occurs less before our eyes than within ourselves. Are the protagonists ultimately a reflection of ourselves? Whose role are we taking on? Are we an active part of the scenery unfolding before and within us?

These are therefore images we resonate and interact with as viewers. In the age of social media, this seems almost natural to us. Ruprecht von Kaufmann himself observes with fascination how so-called users employ narratives to form their own personal identities. These are the manipulated, subjective truths that certain images are designed to outwardly convey. What sticks in the mind when looking is an enviably beautiful (beautified) portrait that touches the viewer emotionally insofar as it creates a sense of lacking and awakens deeply hidden needs. In a nutshell, Ruprecht von Kaufmann artistically captures this discrepancy between reality and fiction in his painting of a female figure from behind ridding herself of her amply proportioned skin. Seen emerging is an almost vanishingly thin, slight person who seemingly shares nothing in common with the one about to be left behind (Take off Your Skin).

Slipping into various roles or manipulated images of oneself, however, is not only a phenomenon of modern times, but runs more or less throughout the entire history of mankind and art; humans have forever been concerned with whom they would like to be and in what role they would like to be seen. Even in ancient times, the concept of the person or persona was commonly used, among other things, as a term for the actor’s mask and the role one plays in acting or in life. Throughout the centuries, portraits, whether in word or image, have frequently been choreographed down to the very last detail: just think of rulers who flaunted their social status, their education, and supposed noble character traits by means of elaborately deployed symbolism, thus constructing their image in the truest sense of the word.

Ruprecht von Kaufmann is particularly interested in such figures who oscillate between worlds, between truth and fiction, and it is hardly surprising that the lyrics of US singer-songwriter Tom Waits serve as one of his sources of inspiration—a musician who is himself hard to pin down, who takes on the identities of various invented figures in his songs and creates the kind of contradictory and complex atmosphere that we encounter in Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s pictures. The painter’s protagonists appear in various guises, some powerfully manipulative or menacing, others needy and vulnerable. We encounter strange hybrid creatures, such as a centaur—half-human, half-horse—asleep in bed, a nude female figure trustingly cuddled up against it (Monster), or a being completely ensconced in a sack-like fabric moving somewhat awkwardly around the room (Die Gefährten [The Companions]. Their true identity remains literally hidden from us, not least because their heads are turned away, are distorted beyond recognition, or even omitted. This is particularly bewildering in view of the fact that we always seek to read and recognize facial features, to position ourselves in relation to others.

When observing the at times complex pictorial spaces, dominated predominantly by people and their actions, it would be remiss of us to assert that Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s work lacks narration. In fact, this is not the artist’s intention: in his view, narrative is a fundamental means for touching people emotionally. He is therefore reluctant to approach painting from a purely formal and intellectual level. This is indeed worth noting, since this pits his images against current negative attitudes in the art context towards narrative in painting. Moreover, this stance is interesting since Ruprecht von Kaufmann comes across as a highly intellectual individual whose images attest not least to an intensive examination of history, politics, art history, literature, ancient mythology, and music.

Nevertheless, what unfolds before the eye of the viewer is not to be regarded in any way as a fully developed story. Rather, they are fragments, or more precisely narrative strands that are only intimated but not resolved. At first, the artist evokes narrative using tangible means that correspond to our established modes of seeing and our subjective horizon of experience, thus offering a seemingly easy way into the imagery. This applies equally to images of circus scenes, mountain landscapes, or autobiographical themes such as childhood and the transition to adulthood—to name just a few.

Subsequently then, our presumed insights are themselves called into question. Ruprecht von Kaufmann thus confronts us with all sorts of incomprehensible details, such as a horse with two hindquarters (Pastorale [Pastoral], an illogically constructed spatial structure, or even gaps in the image, which, viewed in isolation, raise more questions than contribute to clarifying the scene. The viewer is specifically encouraged to give his fantasy free rein, to resolve what is at odds, and to convert the illogical into the logical. “The image,“ says Ruprecht von Kaufmann, “only actually comes into being within viewers themselves.” Narrative fragments thus serve as a bridge the artist constructs for us, while he himself lingers around its base and retreats after encouraging us to continue onward.

Another aspect that runs counter to the purely narrative nature of Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s work is the absence of a fully fleshed-out concept before setting to work. He begins with a vague idea that he allows to guide him. Only in the course of the painting process does it become clear what the painting is all about.

The artist himself likes to refer to the principle of “serendipity“, meaning observing something by chance you weren’t looking for, but which turns out to be a new and surprising discovery. This very principle is reflected in the creative artistic process of Ruprecht von Kaufmann, who freely proceeds from one idea to the next without an overarching concept in mind. A coincidental connection crops up here or there, or a change of direction is undertaken, at times making for unexpected discoveries. Bored-out holes or the application of collage-like elements can develop as a result, breaking up the surface and setting it in motion.

Titles for the paintings are also typically only worked out in the course of the creative process. If, as an exception to the rule, the title is decided upon beforehand, it will reference a sentence, a statement, or a song title that has inspired the artist—such as Babe I’m Gonna Leave You or You never know . But what takes shape then on the image ground is a distant cry from pure illustration.

In general, the titles are in a certain way often surprisingly ironic—when, for instance, there is almost nothing more left of the top of the head of the person portrayed in My Thoughts Grow so Large on Me (2016) than spatula-applied paint remnants, which are more reminiscent of refuse than higher-minded activity. Or Der Entertainer, whose head consists solely of a plume of smoke. Or when the sleeping couple in Rude Awakening slides upside down off the downward sloping bed, as if being literally disposed of. It goes without saying that a humorous title can relativize the gloom and heaviness of the image theme when a hound-from-hell-like creature tears away at another beast and is simply titled Sorglos [Carefree]. A riveting contrast emerges, reminiscent of films by Martin Scorsese or Quentin Tarantino, where a scene marked by brutality is often accompanied by cheery music.

Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s manner of playing with our typical modes of perception in his paintings keeps the eye of beholder constantly in motion. It seeks out a pivot point, finds it, is distracted again, then potentially returns to the earlier point and drifts off from there in another direction. Physically the moving up and down in the space in front of the painting also does not seem to provide sufficient clarification. Potentially paradigmatic of this is the work In the House , in which the viewer moves—reminiscent of a film sequence—from left to right through a house. A total of six locations are traversed; beginning with the stairwell, the viewer is led deeper and deeper into the interior until suddenly finding himself outside the house.

Significant for Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s work is the variation in perspective that is particularly easy to comprehend here, given the artist’s alternating between a bird’s-eye view and an only slightly elevated observer’s point of view, once diagonally from the left, and then, in the next instant, diagonally from the right. The darting of the eye creates in viewers a sense of insecurity, even an oppressive feeling—specifically when the artist shows us an acrobat from behind standing on a swing at a dizzying height looking down at the floor of the circus ring, in a moment of maximum concentration and tension. It almost feels as if the floor is being pulled out from under our feet—as if it were up to us to swing the swing and whirl through the air like an aerial acrobat (Der Trapezakt [Trapeze Act] . The visual angle of the painting but also the very shape of the painted panels raise questions when a multi-element work like State of the Art (p.58), reminiscent of a foldable altarpiece, has an asymmetrical outer shape that would never allow it to function as such.

While Ruprecht von Kaufmann has been creating his works in oil on canvas for many years, 2014 marked a turning point when he decided to use linoleum as painting surface and has since then been doing so consistently. The multi-part portrait series Die Zuschauer [The Spectators] (2014) serves as an example of this switch: peering out at us from fifty-five DIN A4-sized panels are various characters or “personalities”; a variety of portraiture forms are employed here, from the head shot to the bust and the head-and- shoulder portrait, to the half- length figure. As you move in, you notice that the portraits almost seemingly dissolve at times. Eyes are drilled out, facial features are only indicated vaguely or in outline or even painted over using a spatula, while scraping threatens to destroy others. Also conspicuous is the assortment of colors we encounter here; the palette ranges from more reserved gray and blue tones to shrill orange, yellow, or bright magenta. Such color experimentation, however, is not only related to the portraits themselves, but also seems to take its cues from the background hues. At times, strange color sprinkles from the linoleum remain evident.

Here we find ourselves at the core source of the color: it is actually the linoleum itself that literally sets the tone for the painting. Ruprecht von Kaufmann came across the material—a mixture of linseed oil and cork—by chance. While doing construction work on his own home he discovered variously colored linoleum panels that soon aroused his artistic curiosity. The material, produced in a variety of shades, promised to become an experimental field of almost unlimited possibilities.

He subsequently ordered a colorful potpourri of 40 x 30 cm panels and experimented extensively with the way the oil paint behaves on the surface of the ground, which, unlike canvas, does not need to be primed due to its material properties. Ruprecht von Kaufmann noticed that while a blank white patch on canvas always looks “unfinished,” the substrate of a linoleum panel can simply be “left alone” when needed [Schmelzwasser [Meltwater] , Revision . Accordingly, he allowed himself to be guided by the material’s various colors, working with the vibrancy of the respective hue as a reference point. A playful process, a dialogue was set in motion, because each image, each color, gave birth to a new idea: violet meets yellow, yellow encounters blue, orange comes across gray-green, magenta runs up against black. Even more experimental are the paintings, in which wallpaper or floors are covered with colorful patterns and the figures framed as if in a jungle, such as in Monster , Auferstehung [Resurrection] , Der Zeuge [The Witness] , or You Never Know. The potential color combinations seem virtually inexhaustible.

The newly discovered material matched Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s long- cherished desire to use color more powerfully as an individual element, in contrast to earlier works, which are characterized by a rather homogenous, muted tonality. The images thus achieve an obvious presence, but still remain subtle enough that they avoid becoming too conspicuous.

In switching from canvas to linoleum, Ruprecht von Kaufmann was also able to fulfill another wish to give individual elements in the image a more graphical quality, thus setting them apart from other areas of the image. If we look at works such as Schmelzwasser [Meltwater], the figures actually seem refined and reserved, as if drawn on paper. The artist likes to emphasize that brushes and paint flow particularly well on linoleum and that it is well suited for the calligraphy of motion. The image background, he humorously remarks, can be “painted over as easily as a botched oil painting,” where the color also remains on the top surface, over underlying layers of paint.

Last but not least, the material, he explains further, is characterized by a certain resistance to pressure compared to canvas. This is of particular significance when Ruprecht von Kaufmann occasionally applies paint to individual parts of the canvas with a spatula.

It goes without saying that the formal changes mentioned also have an effect on content. Both graphical elements and individual areas left unpainted in the background at times lend the pictures a degree of abstraction that enters into an exciting dialogue with the rest of the painting. If one looks at the last works Ruprecht von Kaufmann created on canvas prior to switching to linoleum—the series with circus scenes—a tendency towards greater abstraction can already be seen in them. In contrast to earlier paintings, the background here is no longer as detailed, but is on closer inspection more reminiscent of sketched-out, geometric forms.

Ultimately this development leads to the linoleum works, in which individual image layers are distinguished from one another even more clearly than before—by graphical elements, by sections that dissolve into carved-out marks, and by fragments of foil applied in a collage-like manner. All of these contribute to the increasingly sculptural quality of the images—almost as if wanting to question the classical art historical distinction between genres of painting, sculpture, and drawing.

Content-wise, the individual layers represent different levels of meaning: for example, the four figures in Schmelzwasser [Meltwater] seen in the foreground of the image and painted directly onto the “raw” linoleum, represent four generations of the artist’s family. From left to right, seated, is Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s great-grandfather, standing next to him his grandfather, followed by his father placed diagonally in the image, and finally ending with the artist himself in a nearly horizontal position. The figures, dressed in military uniforms, are arranged clockwise, as if alluding to the factor of time and thus to transience.

It is interesting to note that Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s figure is only rendered graphically in outline, therefore escaping our perception, so to speak, while his forebears enjoy a greater physical presence. It seems as if the artist is alluding to the fact that his life can still be “filled out.” Rising up in the background behind the figures is an impressive mountain range, whose mid-section, now a melting glacier, has been removed and broken up by marks gouged out of the image ground.

Based on the clothes they are wearing, the figures shown are not only family members but also four generations of alpine troops. Ruprecht von Kaufmann, who completed his military service in mountain rescue, emphasizes how much this time fostered his love of nature. His abiding sense of responsibility towards it and, related to this, towards all future generations, is echoed in particular in the mountain theme that recurs throughout his body of work. This is where the location of yearning and the memorial are united—the latter in particular when the artist expresses the threat of melting glaciers and icebergs, not only in the work Schmelzwasser [Meltwater] mentioned above, but also in Jannu , Der Fjord [The Fjord], Natur [Nature] and Landschaft [Landscape]. Especially in the context of the current debate on climate action and the global Fridays For Future movement, these images are more compelling than ever.

It is clear that Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s paintings should never be thought of solely in a subjective-autobiographical context, but that, above and beyond this, they must also be considered from a global, universally valid perspective. These are deeply personal images that we are only able to access via our own emotionality. In them we search for, recog- nize, question what is presented and develop it further. The power and powerlessness of the protagonists reflect and move us, above all because they show us how mutable man is, in both a negative as well as positive sense. The step from perpetrator to victim—and vice versa—is often less than a stone’s throw away from each other, and in this peculiar entangling we have a mutual effect on one another. In Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s painting, man’s facets are as varied and diverse as the range of tonalities between black and white. As viewers, we are challenged to enter into a dialogue in order to come to this realization in a dynamically variable manner.

Ruprecht von Kaufmann访谈:像执导一部电影那般绘画著

像执导一部电影那般绘画著

1974年诞生于幕尼黑,Ruprecht von Kaufmann是一位目前生活与工作于德国柏林的当代画家。Von Kaufmann以他具象的作品获得了国际认可,主要作品方式包括油布上的绘画与炭笔素描。这位德国艺术家以他灵活的笔触与特殊的用色风格将自己与大多数当代具象画家作出区分。强烈的画风游走于超现实主义与荒谬主义边缘,von Kaufmann用人物充填画作内容与风景;从日常生活中汲取作品灵感作为对现实的评论,唤起耐人寻味的叙事与迷人的图像。

Julien Delagrange (JD): 首先,欢迎来到Contemporary Art Issue;谢谢你花时间来接受访谈。

Ruprecht von Kaufmann (RVK): 这是我的荣幸!

JD: 开启此次对话的唯一方式,就是先恭喜你最近发表了专题著作Ruprecht von Kaufmann: 2013 – 2020;这几乎是一部印刷版的回顾展,对任何艺术家来说都是一个真正的里程碑。你能带我们聊聊这本书的内容吗?

RVK: 我在2013年自己开发了油布绘画的作品领域。在那之前,我正将我的绘画推向了一个新的方向;简化画作的背景并在完成的作品之中留下一些可见的底层绘画。这样的作品显得更有粗糙感、更像素描画。而且,我觉得这样风格的作品更切中要害也更有影响力。这种变化的奇怪之处在于,我一直努力著想要将我的作品推向什麽方向,然后这扇门突然打开了,而我只需要走过它即可。

而2018年时,当我首次开始思考製作一本新书时,记录这些关键转变并给予我的重点画作一个展现平台这件事似乎非常重要。这就是为什麽这本书具有回顾性质。在与我的妻子讨论时—她非常支持我的工作并且是我这本书的设计者—我们产生了不以时间序展示作品的想法,而是将它们重组为重叠的主题,将不同年代的作品相互连结起来。儘管出版商一开始也抱持著怀疑的态度,我很高兴我们选择了这条路;这样的作法让整本书读起来更生动有趣。Sylvia Volz出色地完成了这项艰钜的任务,成功地将所有内容整合进她的文字之中。我认为这是能进入我的绘画世界的重要邀请。

不过,COVID-19疫情的影响几乎使计画卡关。对于在2020这个如此不可预测的一年进行这件事感到十分不确定。幸运的是,柏林Gutshaus Steglitz的市立美术馆以及慕尼黑附近的Buchheim博物馆在这段时间提供我开设个展的机会,也因此从这裡获得了一些金援。如此的发展才最终使得整个计画得以顺利进行。这样的一本书是需要协作努力的;如果没有后面这一大群人的支持,我完全没有办法完成这件事。太多人需要感谢,我就不在此一一列举了!

JD: 通常专题著作或回顾展是艺术家反思其作品的关键。这本专著对你的艺术实践或方向有影响吗?

RVK: 老实说,其实还好。我一直都不是那种会回头看的人。就像爬山时,上次的攀登一点也不重要,下一次的攀越才是重点。对我来说,绘画也是如此。

同时,是的,能够产出这样一本书很棒,因为它提醒著过去几年你在生活中做了些什麽事。但对我来说,改变与持续发展工作始终是不可或缺的。如果我只是重複做著以前一直在做的事,我还不如从事其他的工作。成为一名艺术家最美好的事,就是因为每幅作品都想要呈现一些不同,展示一个新的自己。

今天我强迫自己逐渐转变与改变,因为多年来我了解到,收藏家、画廊、与艺术评论家无法如此快速的跟进;你需要给他们时间去追上脚步,所以需要以思考引导他们。有好几次,我几乎失去了所有愿意接受我作品的收藏家,而我不得不去建立一个新的收藏家清单,只因为他们不喜欢我当时的创作方向。而这只是工作的一部份。

JD: 这本书汇集了你2013至2020年的作品,你认为这其中是否有显著的改变发展吗?

RVK:当然,我会这麽说。如同我前面提到的,2013年为我的作品带来了巨大的转变,而书中的第一幅画仍然是画布作品。然后接著可以看到我如何探索不同的途径与管道,而这因此改变了作品中呈现的材料与思维。我的英雄之一是Beck (一位音乐家),我喜欢那种永远猜不到他下一张专辑会带来什麽的感觉;唯一可知的就是一定会有些不同。所以,在这本书中,读者可能不会读通整本书后还喜欢每一幅画;但是可能,而且希望,其中的一些作品会逐渐与读者产生共鸣,而读者也会因此喜爱上这些一开始可能没有连结感的画作。

比较可惜的是,这本书没有包含一些比较小的作品。那些通常是我的实验基础,并且填补了我某些大型作品间的步骤;但是把这些作品包含进去的话,会太过广泛。所以未来可能还会再有另一本书单独呈现小型作品。

JD: 正如你提到的,可惜现在仍然是COVID-19的疫情期间。你如何经历这场疫情,以及它对你或你的作品是否有任何影响?

RVK: 疫情带来的是一场複杂的经验。一方面来说,我蛮享受这期间的缓慢步调,这让我有更多时间作画,减少组织展览的时间。这同时也让我思考更多其他可能的途径,包含重新投入教学。我喜爱教学,但这是一件十分耗时的事;而疫情让我重新思考这个选项。

然后是那些隐藏的展与取消的活动。我现在在柏林Gutshaus Steglitz市立美术馆有一场展览,但却没有人可以欣赏它,这真的是个很悲伤的体验。即使我已经比其他人更习惯较少的社交接触,我对于社交隔离也逐渐感到压力。但我尽量不让自己太过担心,专注于未来以及如何持续前进。到目前为止,我的艺廊在疫情期间都努力坚持著。而我真正最担心的是我的孩子,他们几乎都失去了一整年的学业与陪伴,这对他们来说真的十分艰难。

而这些体验最后可能会默默存在于我的作品之中;当下的经历通常会需要花点时间通过记忆的滤网并重新组合成为绘画灵感。

JD: 没有面孔的脸反覆出现在这七年的作品之中;模糊的、躲藏的、隐晦的、以Impasto厚涂手法,或者有时候直接没有涂抹的表现方式。这个策略是如何产生的,以及为什麽?

RVK: 我希望我画作中的人物不是特定的人,而是特定类型的对象。所以我有意识地在我的画作之中使用「肖像」。对我来说,画作在后来透过观者的欣赏才会变得生动。而对观众来说,如果他们能够在自己的生活经验中识别出画作裡的对象,他们便能够将这幅画变成他们自己所拥有的体验。所以我在具体化人像时也尽可能地减少其中的限制。

JD: 在过去的二十年裡,这样呈现图像的方式变得越来越明显。你对这点有什麽看法?为什麽我们对于没有脸孔或者欣赏无脸的图像衝击感会如此强烈?

RVK: 我们透过脸孔与他人建立连结;人们认为自己能够从眼睛裡「理解」他人,而且我们认为情绪是通过脸上表情而传递的。但是如果失去这样的线索,我们就会被抛回自身;我们直接地对透过姿势或肢体语言所传达的情绪产生同情与共鸣。这样的反应更加的微妙;当表面看似无害且平静时,有股激流将我们拉进画中。当情绪被激发后,我希望观者能够对我的画作产生强烈情绪反应。

JD: 是否绘画本身有时候也会有模糊或隐藏脸孔的需求?

RVK: 模糊或是抹除是我呈现画作常见的手法,我希望这些作品带有一些生涩感与流动性,如果我在某些部份做了太多工,这样的效果就会消失。所以当我觉得它们变得太过紧实与精确时,我常常会使用刮刀把洞的区域挖除,使它们回到一开始残馀的状态。破坏与重置可能会耗上一段时间,但我希望失败的状态仍然可见。对我来说,这样的轮廓更加可信,因为它们有缺陷,就像人类一样。但是让错误可见也呈现出我脆弱的一面;只有当你允许自己变得脆弱时,才能建立起真正的连结。而我希望我的作品能与观众建立连结。

JD: 身为一位画家,可以说你是一位发自内心作画的艺术家。直觉在你的创作过程中扮演什麽角色呢?

RVK: 直觉一直是绘画过程中十分重要的一部份;这就是绘画与观念艺术之间的区别。绘画过程是一系列连续且有时候是递增的决策。当然,其中有些决策,通常是剧烈的或戏剧性的,是经过精心且深思熟虑计划过的。然而,如果在没有意识的思考过程中做出太多次要的决策,那就大大低估了这些决策的重要性了。就像开著车在路上行进一样,是的,你会在转弯时做出思考;但是整个驾驶过程中,我们大部份的人却都是下意识的在行动。

然而,最重要的是,别低估失败与快乐的错误。它们无法被计算与预测,但是当它们发生时,有时会因此决定一个你之前从未想过尝试开始的新方向。有时候它们会使一个新的灵感成形并帮助你更加精准的行动。我想这就是过去人们常说的「缪斯」。有可能某幅画突然握有掌控权,明确的告诉你它需要些什麽。而我的职责就是后退一步并追随灵感的引导。我发现这样的方式通常会带来比我期望更好的画作。所以这是一个既直觉又满是计划与概念式思考的过程。而经验的累积让这两者之间的界线越来越模糊与通透。

JD: 就我个人而言,当我浏览你的作品时,最让我震惊的是你构图与人物的高度多变性。有些图像似乎超越了荒谬主义,描绘出即使是狂热的梦境也无法诱发的场景。你可以告诉我们更多关于你如何产生这些构图与图像的思维吗?

RVK: 构图可能是关键,我对构思佈局深深著迷,它们是我每幅画作的中枢并提供了许多影响绘画情感表达的可能性。有可能是以十分井然有序的构图来对抗极端的图像,或者反之亦然。我一直很羡慕电影导演,因为他们有时间顺序、音乐与声音。所以对我来说,在绘画中带入一种之前/之后的感觉是很重要的;那是一种一定是某些什麽事情逐渐导致出所描绘时刻的强烈感觉,并且体认到接下来势必还有什麽会发生。以这种方式思考我的画作为我开启了许多表达的可能性。

JD: 关于2015的Die Gefährten (译:伙伴们),看到这幅特别的画作时,我不禁微笑了起来。看起来像是一隻被变形服套住的小恐龙?像是一段纯科幻情境与某种幻觉的有趣交集。可以请你说明这整个过程吗?包含画作是如何产生的,以及我们应该/可以用什麽方式理解这幅画?

RVK: 其实没有什麽正确的方法来理解一幅画。就是允许自我完全融入绘画世界中的内部逻辑,潜入情绪之中。我试著用我的画作来创造一个「平行」现实,这在某种程度上映出了我们的自我,却又奇怪地让人感到不安;就像感受我们自己的行为在外面的人眼裡看进来是什麽样的感觉。因此,藉由允许自己融入这幅画作之中,理想的情况下,我希望观者从中走出来时能同时带出对自己生活有些改变的观点。

这幅画中,主角是那位蹒跚而行的「怪物」。我喜欢你这个被变形服套住的恐龙的描述。我试图去捕获这隻看起来有点舒适、柔软、且无害,但却又同时让人感到恐惧的生物;因为它的形状难以让人辨识且朦胧,它感觉既熟悉又异常陌生。

然后接著是这幅画命名中所指的夥伴們;那些被摆放在置物柜裡的男人们背对著那隻怪物。作品的灵感来自奥德赛;那裡—如同许多英雄故事那般—有著奥德赛的手下们,他们是整个冒险旅程裡忠实的伙伴。但我们却从不知道他们的名字或更多与他们有关的资讯。他们是可被取代的替身、步兵、是神话中的「杂耍鲍伯」,他们是抛弃式产品。当你需要一隻可以变成猪的对象,只要随手从衣柜中拿取一个即可。

儘管这幅画有点黑暗且喜怒无常,但这并不是一件意味著严肃的作品。我的画作裡面通常带有很多幽默;所以我很高兴它让你微笑。

JD: 你作品中的另外一个特点,在各种场景与构图中提供著视觉连续性,那就是你的用色风格。我注意到作品中有许多的蓝色、紫色、粉红色、以及绿色佔据了你作品中的整体视野。这些色彩似乎在证实我们所见并非现实。

RVK: 当我开始绘画的时候,我深受早期大师们的影响。我使用的是「老大师风格」,因此,我的画作有那样的色彩与光线。但我总觉得不太对劲;那样的光线看起来不像现在的光影,有著霓红灯与各种五颜六色的光源。我想要的色调比较像是感觉在水下,或者是在灯光昏暗的夜店之类的地方。那些环境让肤色看起来不太健康或无法呈现粉嫩色感,而是以绿色或蓝色为主。呈现出来的效果就是我们确实没有看到真实的东西,而是现实的反映,我们正在经历著某种白日梦。就像在梦中那般,东西看似熟悉,却又不完全像在醒著的生活之中。

JD: 我们可以确定一个世代的当代具象画家的特点是超现实主义与深植于存在主义之中那更黑暗的氛围。在我的浅见看来,你一直是这个世代的领军人物;你对于当代绘画这种趋势的看法如何呢?

RVK: 其实,我对于当代绘画的「当下趋势」不是非常确定。我只是一直对于尝试将我的作品逐渐地推向我觉得应该前进的方向这种事感兴趣,然后藉此画出我脑中出现的灵感。而这是以过份关注他人在做些什麽为代价的。这听起来或许有些自大,但是对我来说,这关乎于我如何分配我的时间。我沉迷于绘画,而我始终在思考著如何获取下一个创意灵感。然后就这样了。当然,对于一个艺术家来说,没有比这个更美好的讚美了;然后还能因此激励其他艺术家,没有比被视为是艺术家的艺家大师更大的荣誉了。然而,这是我无法定论的众多事物之一。我能做的,就是完成我的工作,仅此而已。

JD: 我认为这让一切变得更加有趣。在与这样的潮流相关的艺术家交谈时会发现这似乎是一种无心而成的现象。大家似乎都只是追随著自己的兴趣和衝动而已,你也是如此。是否有哪些艺术家或同事是你认为能够与你的工作产生密切关联?这其中是否有相互的影响?

RVK: 当然,我正在疯狂地从中偷取东西。但是我很难把这些限缩到只有几个名字。而且,通常我尽量不看我非常欣赏的人他们的IG分享,就是因为害怕受到太多影响。简单列举几位就好,我欣赏Lars Elling (生于1966年)、Justin Mortimer (生于1970年)、以及Nicola Samorì (生于1977年)。

但是更重要的是,我从歌词与书籍中汲取灵感。我喜爱文学,而且我沉迷于有声书 (以及咖啡来成就我的成瘾三部曲)。一本好书可以在我脑中激发出上百万张图像来运行。这就是为什麽我的许多作品都是以歌词或散文来命名。当然,还有电影:它们对我的巨大的影响。我在作画的时候,我的脑子裡就像是在执导一部电影。在绘画过程中会产生许多需要找到解答的问题,从构图、到光影、到一日中的时段、到衣服、色彩、背景、以及如何剪裁图像。所有的这一切都影响著最终的成果,就像导演一部小电影那般。

JD: 我很期待你未来将要执导的「电影」—画作。谢谢你宝贵的时间,更感谢你对艺术、画作、以及生活的真实且有趣的看法。Ruprecht von Kaufmann,与你的访谈过程十分愉快,谢谢。

Painting as if Directing a Movie

Ruprecht von Kaufmann, born in 1974 in Munich, is a contemporary painter living and working in Berlin, Germany. Von Kaufmann achieved international recognition with his figurative body of works, mainly consisting of oil paintings on linoleum and charcoal drawings on paper. The German artist distinguishes himself from the bulk of contemporary figurative painters with his dynamic touch and unique colour palette. Strongly marked by an edge of surrealism and the absurd, von Kaufmann populates interiors and landscapes with figures. Drawing inspiration from daily life as a comment on reality, evoking intriguing narratives and captivating images.

Julien Delagrange (JD): First and foremost, welcome on Contemporary Art Issue. Thank you for taking the time for this interview.

Ruprecht von Kaufmann (RVK): My pleasure!

JD: The only way I can start this conversation is by congratulating you on your most recent monographic publication, Ruprecht von Kaufmann : 2013 – 2020. Almost a retrospective in print, a true landmark for any artist. Could you talk us through the catalogue?

RVK: In 2013 I had discovered linoleum for myself as a painting ground. Just before that I had pushed my painting into a new direction, of simplifying the backgrounds and leaving some of the underlying drawing visible in the finished painting. The paintings became rougher and more sketch-like, but at the same time – I felt – more to the point and more impactful. The strange thing about these kind of changes was, that I had been striving to push my work into that kind of direction for a while, and then all of a sudden this door opened and all I needed to do was walk through it.

In 2018 when I first started thinking about a new book, it seemed very important to document these crucial shifts, to give those, for me very pivotal works, a platform. So that’s why it has some retrospective qualities. In discussion with my wife – who is incredibly supportive of what I do and who has designed the book – we came up with the idea of not showing the works in chronological order, but to restructure them into overlying themes that tie very different pieces from different years together. Even though the publisher was sceptical at first, I am very happy we went that way. It makes the book more lively and interesting to read. Sylvia Volz did an incredible job with the very difficult task to tie it all together in her text. I think it is a very important invitation into the world the paintings encompass.

The pandemic nearly chocked the project. My gallery – Gallery Thomas Fuchs in Stuttgart – who has co-financed the book was really uncertain if we should go through with it in an unpredictable year like 2020. Fortunately two museums, the city owned Gallery at Gutshaus Steglitz in Berlin and the Buchheim Museum near Munich, offered me solo shows at around the same time, and with that came some financial support from their end. That finally got the project off the ground. A book like this is a collaborative effort, that I couldn’t have realised without the support of a holehost of people. Too many to name them all here!

JD: As often, monographs or retrospective shows are key moments for an artist to reflect on their work. Does the monograph have an effect on your artistic practice or direction?

RVK: Not really, to be honest. I have never been much of a looking back kind of guy. It’s like mountain climbing. The last climb isn’t of any importance. Only the next one counts. For me it’s the same with paintings.

And at the same time, yes, a book like this is great, because it reminds you of what you have done with your life for the past couple of years. But for me, changes and the continuous evolving of my work has always been essential. If I would just repeat what I have been doing before, I might as well be working in any other job. What is so fantastic about being an artist, is that every painting wants something different, something new from you.

Today I am forcing myself to make shifts and changes more gradually, because I learned over the years, that collectors and galleries and art critics don’t follow along as quickly. You need to give them time to catch on, lead them along with your thinking. Several times, I have lost almost all of my collectors and had to built up a new collector base, because many just didn’t like the direction I was taking with my work. That’s just part of the job.

JD: The book compiles your work from 2013 up to 2020. Would you say there is a visible development?

Absolutely, I would say so. As I have mentioned before, 2013 brought huge shifts in my work and the first paintings in the book are still painted on canvas. And then you can see the process of how I explored different routes and avenues, that the changes in material and in thinking offered. One of my heroes is Beck (the musician). I love how, with his albums, you never know what you will get in the next one. The only thing you can rely on is that it will be different. So in the book you probably won’t read through it and like every painting. But maybe, and hopefully, you will grow to understand and love some of the ones that you didn’t connect with at first.

Unfortunately the book doesn’t include the smaller works, they often are my experimentation ground and could have filled in some of the steps in between larger works. But it would have gotten too extensive. So maybe there will be another book with just the smaller format works in the future.

JD: As you have mentioned, sadly, there still is the issue of Covid. How did you experience the pandemic and in what manner did it have effect on you or your works?

RVK: The pandemic has been a mixed experience. Partly, I enjoy the slow pace, because it allowed me to spend more time painting and less time organizing exhibitions. It also has led me to think about other avenues more, like maybe getting back into teaching as well. I love teaching, but it’s also such a time drain. But Covid has got me thinking about that again.

Then there are all the concealed shows and the cancelled fairs. I have an exhibition in the City Gallery Gutshaus Steglitz in Berlin right now. But no one can see it. That’s a really sad experience. And even though I am used to less social contact than most people, I am starting to feel the strain of social isolation. But I try not to worry too much and focus on what’s ahead and how to keep going. So far my galleries have been doing great work to power through the pandemic. But really I am most worried for my kids right now. They have more or less lost an entire year of schooling and of companionship. For them it’s been really rough.

All of that might creep into my paintings eventually. It usually takes a little while for current experiences to filter though memory and be reassembled into ideas for paintings.

JD: A recurring characteristic throughout this body of works of seven years of painting is the implicit absence of faces. Blurred, evaded, hidden, destroyed with a strong impasto or sometimes simply not painted. How did this strategy come about and why?

RVK: I want the people in my paintings not to be a specific person, but a specific type of person. So I am consciously avoiding ‘portraits’ in my paintings. For me a painting becomes alive through the viewer who encounters the image later on. And for the viewer it becomes possible to make the painting their own if they recognize figures out of their own life experience. So I try to leave the figures as open as possible while being as specific as necessary.

JD: The implementation of this image formula has been increasingly visible over the past two decades. What’s your viewing point upon this matter? Why do we feel so strongly not to paint faces and/or view pictures without faces?

RVK: We make connections with another person through the face. We think we can ‘read’ othersthrough their eyes. We also think that emotions are transported through the expressions on a face. But if those clues are missing, we are being thrown back onto ourselves. We intuitively empathise with emotions that are communicated through posture and body language. This reaction is much more subtle. It’s like a riptide that pulls us under and into the painting, when the surface looked harmless and quiet. But then your own emotions that are being triggered. I want the viewer to have a strong emotional response to my paintings.

JD: Does painting itself sometimes demand to blur of hide the faces?

RVK: Blurring or erasing is a regular part of my painting practise. I want the paintings to have a certain rawness and fluidity that would get lost if I laboured too much over a certain section. So I often take a scraper and scratch out hole areas when I feel they have gotten too tight and too precise and then work back into the remnants of what was there before. That process of destroying and rebuilding can go on for quite a while. I want the failures still to be visible. To me the figures look more believable that way, because they are themselves flawed, like actual human beings. But leaving mistakes visible also allows a presence of vulnerability on my end. A true connection is only possible when you allow yourself to be vulnerable. And I want the paintings to connect with their audience.

JD: As painter, one could argue you are a painter who paints from the heart. What role does intuition have in your creative process?

RVK: Intuition is always a very essential part of the painting process. That’s what differentiates painting from Conceptual Art. The painting process is a continuous series of sometimes incremental decisions. Of course some of these decisions, usually the drastic and more dramatic ones, are well planned and thought out. But to brush over the many, many minor decisions you take without a conscious thought process, would be greatly undervaluing their importance. Like driving a car down a road. Yes you think about it when you need to take a turn. But a large part of the driving process happens subconsciously.

But most importantly, don’t underestimate failures and happy mistakes. They can’t be calculated and anticipated. But when they happen they sometimes dictate a new direction that you hadn’t thought of starting out. Sometimes they crystallize an idea and help you in being more precise. That’s what people used to call ‘a muse’ in the old days, I presume. It can happen that a painting takes control, tells you exactly what it needs. And then it’s my role to step back and follow that lead. I find that this usually results in a better painting then I could have hoped for. So it’s a process that is just as much intuition as it is planing and conceptual thinking. And experience makes the borders between the two more and more blurry and permeable.

JD: Personally, when I am browsing through your work, what staggers me the most is the immense variety of compositions and figures. Some images seem to go beyond the absurd, depicting scenes that could not even be induced by a feverish dream. Could you tell us a bit more how these compositions and images are built?

RVK: Composition is probably the key. I am obsessed with compositions, they are the backbone of every painting and offer so many possibilities to influence the emotional expression of a painting. It’s possible to counter very extreme imagery with a very orderly composition or vice versa. I am always envious of film directors, because they have a timeline, music and sound available to them. So to me it’s important to introduce a sense of a before or after into the painting. A strong sense that something must have led up to the depicted moment and that something will happen afterwards. Thinking about my paintings that way opens up so many possibilities of expression to me.

JD: I can not help but smile when seeing this particular painting, Die Gefährten – The fellows in English – from 2015. It looks like a small dinosaur is captured in a morph suit? A fascinating intersection of pure science fiction and a hallucination of some sort. Could you talk us through the process, how the image originated and how one should/could approach this painting?

RVK: There is no right way to approach a painting. It’s allowing yourself to buy into the internal logic of the painted world, to dive int o the mood. I try with my paintings to generate a ‘parallel’ reality, that somewhat mirrors our own, but is strange enough to feel unsettling, like how our own behavior might look to someone looking in from the outside. So by allowing yourself to slip into the painting, I hope you come out of it with a slightly altered perspective on your own life. Ideally.

In this painting the main character is the ‘monster’ lumbering about. I like your description about a dinosaur captured in a morph suit. I was trying to get this creature, that looks sort of cozy and soft and unthreatening, but at the same time feels unnerving, because the shape of the thing is unreadable and obscured. It is at the same time familiar and strangely alien.

Then there are the Companions that the painting is named after. The men that are placed in the lockers turning their back to the monster. The inspiration is taken from the Odyssey. There – as in many other hero stories – are Odyssey’s men, who are his faithful companions throughout his adventures. But we never learn their names or anything more about them. They are exchangeable stand-ins, foot soldiers. The ‘sideshow-bob’ of mythology. Disposables, that you can pull out of the closet, whenever you need someone whom you can turn into a swine.

Even though the painting is kind of dark and moody, it’s one that isn’t meant to be all serious. Usually there is a lot of humour in my work. So I am glad that it makes you smile.

JD: Another characteristic aspect of your oeuvre, offering visual continuity throughout the variety of scenes and compositions, is your colour palette. I note there are many blues, purples, pinks and greens dominating the overall view of your works. They seem to affirm what we’re seeing is not reality.

RVK: When I started out in painting, I was very influenced by the old masters. I was using the ‘old master style’ and therefore my paintings had that coloration and light as well. But I always felt it wasn’t quite right. The light didn’t look like light looks nowadays, with neon-lamps and all kinds of colourful light sources. I wanted to have a coloration that feels more as if being under water, or in a badly lit night club or something. Where skin tones don’t look healthy and pink, but are dominated by greens and blue. The effect would be exactly that we do not see something real, but what we are seeing is a reflection of reality, that we are moving through some kind of daydream. Like in dreams, things look familiar, and also not at all like in waking life.

JD: One can ascertain a generation of contemporary figurative painters marked by surrealism and a darker atmosphere rooted in existentialism. In my humble opinion you have been one the leading figures for this generation. What’s your view on this tendency in contemporary painting?

RVK: Honestly, I am not very firm about ‘current tendencies’ in contemporary painting. I was always just simply interested in trying to push my work more and more to where I felt it needed to go, to paint the things that go through my head. That has come at the expense of looking too much at what others are doing. That might be arrogant, but for me it’s a matter of how to spend my time. I am addicted to painting and I am always thinking about how to get the next creative hit. So there you are. Of course there is no greater compliment for an artist, then to be able to inspire other artists, no greater honour then to be seen as an artist’s artist. But that’s one of the many things that aren’t for me to determine. All I can do is make my work, that’s it.

JD: I think that makes it even more interesting. It seems to be a very unintentional phenomenon when speaking with the artists associated with this tendency. They all seem to be following their own interests and urges, as do you. Are there certain artists, colleagues, with whom you can identity your work with? Has there been a reciprocal influence?

RVK: Of course, I am stealing stuff like crazy. But it’s hard to narrow it down to just a few names. And usually I try not to look at the instagram feed of people whose work I admire too much out of fear to be influenced too much. I adore the work of Lars Elling (b. 1966), Justin Mortimer (b. 1970) and Nicola Samorì (b. 1977) to name just a few.

But even more, inspiration I draw from song lyrics and from books. I love literature and I am addicted to audio books (and coffee to complete the trilogy of my addictions). A good book can trigger a million images in my head, that I can just run with. That’s why a lot of my titles are quotes from Song Lyiks or prose. And then of course movies: they have been a huge influence on me. In my head I am directing a film as I paint. There are so many questions that need to be answered in the course of a painting; from composition, to lighting, to time of day, to clothes, colours, backgrounds and how the image will be cropped. All of which influence the final outcome. It is like directing a small movie.

JD: I’ll be looking forward for the ‘movies’ – paintings – you’re set to direct in the years to come. Thank you for your time and even more for your genuine and intriguing view on art, painting and life. It has been a true pleasure, Ruprecht von Kaufmann.

虚无的艺术

by Daniel J. Schreiber

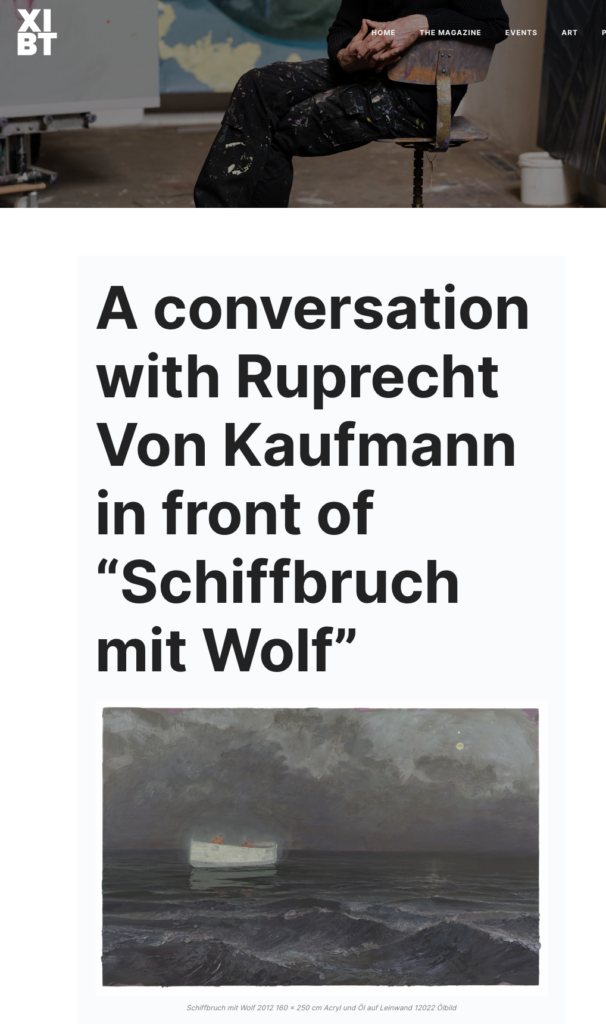

当Ernst Ludwig Kirchner的Große Berglandschaft与Ruprecht von Kaufmann的Der Fjord于2021年首次一同在Buchheim博物馆展出时,那简直是一场泰斗会面的场合。这两个山景作品各有二乘六米;除了作品的尺寸、极端的横幅模式、以及主题之外,这两件巨幅作品似乎没有什么共同之处。在Kirchner的画作之中,观者会有种在仲夏时期,身处于高山山谷间草地、树木、与巨石之中的感觉。另一方面,Ruprecht von Kaufmann的作品则是采取一个较为冷漠且有距离感的角度;观者像是在峡湾旁远眺白雪覆盖的高山山脉。

Von Kaufmann有许多能够近距离研究Kirchner巨幅作品的机会;他在图青(Tutzing)的施坦贝尔格湖(Lake Starnberg)长大,距离Buchheim博物馆所在的Bernried仅七公里之远。Kirchner在那里的主要作品是博物馆创办人Lothar-Günther Buchheim的部份表现主义收藏品;然而,当博物馆于2001年成立之时,Kaufmann早已离开并走向世界了。高中毕业后不久,他便前往洛杉矶的Pasadena College of Art就读艺术;此后,他住在洛杉矶、纽约、并且于2003年搬至柏林。但是当他想见父母或者思念他年轻成长过程中的当地景色时,他就会回到图青;而他也会去欣赏Kirchner的Große Berglandschaft。

1931年,Kirchner将几乎没有混色的构图结合他大胆的笔刷涂抹在作品表面的粗麻布上。暖色调橙棕树干与巨石在森林与草地的翠绿之中显得格外显目。树木与巨石的深蓝轮廓线条强调了对比的交互作用。浅蓝色的天空,像楔子般地插入山脊之中,将观者的注意力吸引至画作中心。这部壮丽的作品是Kirchner在1931年于Gasthof “Zum Sand”,一间位于Davos Frauenkirch的小旅馆,演出的混合唱戏剧表演所创作的;作品明显没有提到具体的地点。作为Paul Appenzeller戏剧“Die Tochter vom Arvenhof oder Wie auch wir vergeben (英文意译:Arvenhof来的女儿,或者当我们原谅之时)”的表演背景,这幅画作充分显露出一种整体的民俗风味魅力。正如Lothar-Günther Buchheim所说的,它是“阿尔卑斯山景观的原型”。

尽管作品是Kirchner在1905年于Dresden所创立的艺术家团体“die Brücke”解散后18年才创作的,这幅大型画作仍然是该团体很好的一个例子。根据Buchheim的说法,Kirchner与他的朋友们认为图像再现实际情况的功能与表达的自由形式两者的追求同等重要。而传达这两种相反的趋势至今仍然是一项持续进行的艺术任务。换句话说,只有从我们的经验视野开始,艺术才能够被理解;并且只有超越它才能变得强大。这在当时与今日都一样真实。

一开始,von Kaufmann的fjord景观作品似乎与这个定义不太相干。画作中细致笔触的逼真精度产生了太大的作用;我们毫无疑问地正在面对的是实际山脉的描绘。因此,我们对这幅画提出的第一个问题是这座白雪覆盖的山在哪里,而不是它是否存在。即便是上面惊人的虹彩也不会破坏它逼真的外观。从William Turner与随后的水彩艺术中,我们感知到艺术家利用自然界中特殊的照明条件,例如日落,将色彩缤纷、富有情调的构图带到画布之中。我们假设自己正在观察一个冬季下午的全景;色谱从右侧边缘的橙色午后阳光到左侧傍晚时刻较冷系的紫蓝色调。

与第一印象相反,von Kaufmann的fjord画作远远超出了我们对所感知的现实。实际上,相较于Kirchner的作品呈现着他所在的时代,fjord更像是地球上所有山景的“体现”,因为von Kaufmann的想像画面是根据他对Landwassertal山谷斜坡的印象。另一方面,身为世界公民的von Kaufmann也曾经是山地猎人、滑雪者、以及登山客;他曾登上各大洲的许多山峰。他所描绘的山脉在哪?它漂浮于空中,无处不在却也不在何处。这幅画是画家于New England、California、Alaska、Norway、他所在当地的Karwendel山脉、以及其他地方的绘画与登山经验所累积出来的基础。

作品的配色方式与实际的光线情况无关;即使色调暗示了浪漫的日落气氛,画作表面落于周边的亮白又大大的中和了这点。相较于Kirchner的画作,构图的概念显然在这里更是至关重要。表现主义的用色风格在此刻重新被诠译著。在整个六米宽的作品上,von Kaufmann从橙色到蓝色之间进行了几乎无法察觉的过渡转化—而Kirchner所强调的两色则是在他的山景画作中创造了一个果断且互补的对比。这两种颜色分别代表着夏天与冬天、白天与黑夜、以及寒冷与温暖;它们是典型的对比。Von Kaufmann仔细雕琢的渐层清楚地表明,世界上的一切都属于同类,即使是最大的对比。

然而,对von Kaufmann来说,最重要的艺术元素并非色彩亦非形式,而是画作其中的虚无!事实上,我们起初很少关注这些空白的原因是在于我们视觉感知的特殊性。在试图了解周边环境时,我们的眼睛会不断地来回移动;这样做的同时,只有小部份区块会显现在水晶体上。而另一个限制是,敏锐的视力只能够在视网膜上的一小部份上呈现;我们的大脑在不自觉的情况下将模糊的图像直接排除掉了,而到达我们视觉皮质的脉冲仅占视觉印象的一小部份而已,甚至比我们搜索的眼睛所扫描的周边图像量少得更多。尽管如此,我们仍然能够获得整体画面的视觉感知,这是基于我们大脑强大的能力,能够根据过往经验与生物参数来补足缺失的讯息。我们的视觉皮质中只有大约10%的神经纤维起源于眼睛,而大脑会将剩余的视觉资讯补足。因此,我们习惯于用很少的资讯得出我们对事物的看法。

Ruprecht von Kaufmann巧妙地向我们展现这个系统有多么容易故障。只有经过几次仔细查证后,我们才会发现,我们所看到的只不过是画作表面那超过60%的弥漫且柔和的白。我们的感知将这些虚无转化成雾濛濛的冬日天空、白雪覆盖的岩石与草地、以及滑过谷底的冰舌。然而,并非每种虚无都是一样。天空露出的是光秃且未加工的底板;而透过一些粗略笔法的帮助,将前景中那白雪覆盖的岩石从我们的想像中诱发出来。除此之外,单纯的底板也以此方式闪耀着,其柔和、弥漫、且略带色调的白是von Kaufmann极其独特的材料选择:我们在这里看到的并非帆布、纸板、或木材,而是油毡

如同我们在美术课中学习到的,这种材料很容易切割与雕刻。而艺术家也利用了这种独特性质,画作上面冰舌所占据的空间,最初便是Kaufmann以宽刷涂抹的厚涂颜料。这样的颜料应用仍有部份保留在图画右下角,也就是峡湾出现之处。水平的笔触让人联想到夕阳映照的平静水面。整幅画的用色风格都是以厚厚的涂抹形式表现,有些甚至延伸到画作的边缘之外。接着,艺术家再用油毡刀依照冰舌形状从画作表面雕刻出来,使其从源头滑过山谷至水中。而残余的漆则仅保留于刀痕之间的山脊上。这样的呈现方式使单色表面活跃了起来,并让它看起来像是冰团表面那多孔洞且破碎边缘的样子。

不过,我们在von Kaufmann的fjord中体验到最大的奇迹是观看冰川时所感受到的立体效果。我们怎么会认为眼前所见的真实冰团,实际上是被切成空心的白色油毡?在这里,艺术家也同样利用我们感知装置的弱点来欺骗我们。严格来说,我们的眼睛无法感知空间性。视网膜上的影像总是二维的,而具有空间感的影像则是仅由我们大脑对视觉印象的诠释。例如,与空间有关的讯息是从阴影和比例获得而来的。而艺术家同时利用了这两者。一方面,镂空的切面随着深入的距离而变窄;另一方面,洼地间的山脊产生了阴影。我们的眼睛无法分辨它是空心的还是凸起的。当我们的大脑需要判断眼前的物件,而它的判断则需基于证据;由于没有人见过下凹形式的冰川,所以大脑便认为这里也因此不会出现这种形式。所以,大脑便会将二维的影像连同阴影转化成向上凸起的雕刻。

但是如果我们更仔细地检查图像,尤其是从侧边观察表面时,我们就能发现自己陷入了视错觉之中。接着因此理解到,我们的想像力已将虚无转化为雕刻。这样的画作鼓励我们以超越自我经验水平的方式进一步思考。我们是否也能以想法填充其他的虚无?有没有可能用一种以朝着洞悉与行动为导向的方式来窥视未来的虚无?难道我们不应该只评估过往和现在的资讯来替未来添加预期的变化吗?特别是冰川这个主题似乎更需要这样的想像力。一张1895年拍摄的Alaskan冰川历史照片启发了Kaufmann的冰川画作。从那时起,大部份的冰川都已经因为地球暖化的关系而融掉了;只有当冰川滑入山谷时所造成的景观变形仍然存在。或许文明化所带来的损失应该被视为一种对想像力的挑战;一个能够在他们所存在的地方展望着一个崭新且更丰富未来的人。

作者:Daniel J. Schreiber (b. 1965)

Daniel J. Schreiber 为德国著名艺术史学家,现任德国施塔恩贝格湖畔贝恩里德幻想博物馆(又名布赫海姆博物馆)的馆长,为收藏德国表现主义艺术作品的指标性博物馆之一。Schreiber 在慕尼黑的路德维希马克西米利安大学学习哲学、民族学、德语和比较民俗学,随后于汉堡大学先后取得哲学、艺术史及民族学硕士学位。曾任职于汉堡工艺美术馆、不来梅贝特西街(Böttcherstraße)艺术收藏、巴登-巴登弗里德布尔达博物馆、罗兰塞克阿尔普博物馆,并于图宾根美术馆担任管理策展人。

THE ART OF THE VOID

by Daniel J. Schreiber

It is a meeting of titans when Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Große Berglandschaft and Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s Der Fjord appear together for the first time in an exhibition at the Buchheim Museum in 2021. Both mountainous landscapes measure two-by-six meters each. Apart from their size, their extreme horizontal format, and their theme, the two monumental paintings seemingly have little in common. In Kirchner’s painting, the viewer has the impression of standing in the middle of a summertime, alpine valley of meadows, trees, and boulders. Von Kaufmann’s counterpart takes a coolly distant position. We observe from a distance a snow-covered alpine mountain range by a fjord.

Von Kaufmann had numerous opportunities to study Kirchner’s monumental painting up close. He grew up on Lake Starnberg in Tutzing, only seven kilometers away from Bernried, where the Buchheim Museum is located. Kirchner’s major work there forms part of the Expressionist collection of museum founder Lothar-Günther Buchheim. By the time the museum was founded in 2001, Kaufmann had long since left and made his way into the world. Soon after finishing high school he moved to Los Angeles to study art at the Pasadena College of Art. Thereafter, he lived in Los Angeles, New York, and moved to Berlin in 2003. But whenever the desire to see his parents and the local landscape of his youth drew him back to Tutzing, he would also go see Kirchner’s Große Berglandschaft.

In 1931 Kirchner applied the composition of barely mixed colors with bold dashes of his brush onto the coarse burlap of his painting surface. Warm-hued, orange- brown tree trunks and boulders stand out against the crisp green of the forest and meadows. The dark-blue linear contours of the trees and boulders underscore the interplay of contrasts. A light blue sky, inserted wedge-like between the ridges, draws the viewer’s attention to the center of the painting. This magnificent work, which Kirchner created in 1931 for a mixed-choir theatrical performance at the Gasthof ”Zum Sand“, an inn located in Davos Frauenkirch, apparently does not reference a specific location. As a backdrop for the performance of the play “Die Tochter vom Arvenhof oder Wie auch wir vergeben” (“The Daughter from the Arvenhof, or As We Forgive”) by Paul Appenzeller, the painting exudes an overall folksy appeal. It is, as Lothar-Günther Buchheim put it, an “archetype of the Alpine landscape.”

Although it was made eighteen years after die Brücke had dissolved, the large- scale painting is a fine example of the art created by the artist group Kirchner co- founded in Dresden in 1905. According to Buchheim, Kirchner and his friends placed just as much importance on the function of the image to reproduce reality as on the striving for free forms of expression. Conveying these two opposing tendencies has remained an ongoing task of art to this day. In other words: art is only comprehensible if it starts with our horizon of experience, and only powerful if it transcends this. That was as true then as it is today.

At first, von Kaufmann’s fjord landscape seemingly has little to do with this definition. The realistic precision of detailed brushwork plays too great a role. There is little doubt that we are dealing here with the depiction of an actual mountain range. The first question we ask of the painting is where this snow- capped mountain is located, not whether it even exists. Even its astonishing iridescence does not undermine its photorealistic appearance. From William Turner and the art of watercolor that followed, we are aware that artists make use of special lighting conditions in nature, such as the sunset, to bring colorful, atmospheric compositions to canvas. We assume here that we are observing a panorama on a winter afternoon. The color spectrum ranges from the orange of the afternoon sun on the right edge of the picture to the cooler purple and blue tones of the twilight hour on its left edge.

Contrary to first impressions, von Kaufmann’s fjord painting goes far beyond our perceptual reality. In actuality, it is much more an “embodiment” of all mountainous landscapes on earth than Kirchner’s painting was in his time, since Kirchner’s imaginary image was based exclusively on his impressions of the valley slopes of the Landwassertal. Von Kaufmann, on the other hand, a citizen of the world and former mountain hunter, skier and climber, has summited many a peak on various continents. Where is the depicted mountain range to be found? It rises up into the sky everywhere and nowhere. The painting is a substrate of the artist’s painterly and mountaineering experiences in New England, California, Alaska, Norway, around his local Karwendel range, and elsewhere.

The color scheme has nothing to do with an actual lighting situation. A romantic sunset atmosphere is hinted at, but the surrounding white of the painting surface largely neutralizes this. In comparison to Kirchner’s painting, it is obvious that a compositional concept was critical here. The expressionist color palette is reinterpreted. Over the entire breadth of six meters, von Kaufmann executes a barely detectable transition from orange to blue—the two colors Kirchner highlighted in creating a decisively placed, complementary contrast in his mountainous landscape. The two colors stand for summer and winter, for day and night, for cold and warm. They are the quintessence of contrast. Von Kaufmann’s measured gradation makes clear that everything in the world belongs together, even the greatest contrasts.

With von Kaufmann, however, the most important artistic elements are not the colors, not the forms, but the voids! The fact that we initially pay the slightest attention to them is due to a peculiarity of our visual perception. In seeking to take in our surroundings, our eyes move constantly back and forth. While doing so, only small areas appear before the lens. Another limitation is that sharp vision is only possible on a small part of the retina. Blurred images are excluded by our brain without our noticing. The impulses arriving in our visual cortex comprise only a fraction of the visual impressions, and are even a far smaller part of an image of our surroundings scanned by our searching eyes. Nevertheless, we get a visual sense of the overall picture. This is based on the enormous capacities of our brain to supplement missing information based on previous experience and biological parameters. Only about 10 percent of the nerve fibers in our visual cortex originate in the eye. The brain adds the remainder of the visual information. So we are used to arriving at our view of things with very little data.

Ruprecht von Kaufmann ingeniously shows us how susceptible this system is to failure. Only after several careful inspections do we notice that we are seeing nothing more than the diffuse, muted white of the painting ground on over 60 percent of the painting surface. Our perception has turned these voids into a hazy winter sky, snow- covered rocks and meadows as well as a glacier tongue sliding over the valley floor. But not every void is the same. The sky reveals the bare, unworked painting ground. The snow-capped rocks in the foreground are enticed out of our imagination with the help of a few sketchy brushstrokes. Otherwise, the pure painting ground shines through here too. Its soft, diffuse, slightly tonal white is the result of von Kaufmann’s very special choice of materials: what we are looking at here is neither canvas, nor cardboard or wood, but linoleum.

As we all know from art class, this material is easy to cut and carve. The artist also makes use of this unique characteristic. The section occupied by the glacier tongue was originally covered in impasto paint that Kaufmann had applied with a broad brush. Part of this paint application remains on the lower right edge of the picture, where the fjord appears. The horizontal brushwork evokes the idea of a calm surface of water illuminated by the evening sun. The painting’s entire palette of hues is seen here in thick smears, some of which extend beyond the painting’s edge. However, the artist carved out the painted surface with linoleum knives following the form of the glacier tongue, which flows from its area of origin through a valley into the water. Remnants of paint are only preserved on some of the ridges remaining between the tool marks. They enliven the monochrome surface and give it the appearance of a porous, broken edge of an ice mass.

The greatest marvel we experience with von Kaufmann’s fjord painting, however, is the three-dimensional effect that occurs when looking at the glacier. How can it be that we think we see the ice masses physically in front of us, when they have in fact been cut into the white linoleum as hollow forms? Here, too, the artist plays a trick on us by exploiting a weakness in our perceptual apparatus. Strictly speaking, our eyes cannot perceive spatiality. The retinal image is always two- dimensional. A spatial image is only created by our brain’s interpretation of the visual impression. Information about spatial relationships is gained from shadows and proportions, for example. The artist makes use of both. On the one hand, the cross-sections of the carved-out hollows become narrower as they recede. On the other, the ridges between depressions cast shadows. Our eyes cannot make out whether it is a hollow or a positive form. So the brain has to decide what is in front of it, and it does so based on evidence. Nobody has ever seen a glacier as a negative form. That’s why this can’t be the case here either, it thinks. And it transforms the two- dimensional image with shadows into a sculptural, positive form.

But if we inspect the image more closely, especially when looking at the surface from the side, we can see that we have fallen for an optical illusion. We realize that our imagination has turned a void into a sculptural body. Here the painting encourages us to go beyond our horizon of experiences and think further. Can’t we fill in other voids with ideas as well? Shouldn’t it be possible to peer into the void of the future in a way that is oriented toward insight and action? Shouldn’t we only have to evaluate past and present information and add in anticipated changes for the future? The subject of glaciers in particular seems to demand such imagination. An historic 1895 photo of an Alaskan glacier inspired Kaufmann’s painting of the glacier. Since that time most of the glacier has melted due to global warming. Only deformations in the landscape created as it slid down into the valley still remain. Perhaps the losses brought about by civilization should be seen as a challenge to the imagination. One that envisions a new, richer future in their place.