作者:迪迪姆・亞則哲 Didem Yazıcı

策展人、作家,新藝術博物館策展人、開羅歌德學院策展人、第11屆上海雙年展基礎策劃人。

敢於成為 Beastville 土地上的另一個人

Daring To Become Someone Else in the Land of Beastville

By Didem Yazıcı

“你將如何找到你完全不知道其性質的東西?”(柏拉圖)我們想要的東西是變革性的,我們不知道或者只認為我們知道變革的另一面是什麼。愛、智慧、優雅、靈感——你如何尋找這些在某種程度上是關於將自我邊界擴展到未知領域、成為另一個人的東西? ”麗貝卡·索爾尼特,迷失指南(2005)

每當你手持一本書在閱讀、參觀展覽觀看繪畫,或僅僅是走在街上,不論是在你的舒適區內還是外面,你是否曾經有過成為另一個人的想法?一種矛盾的本能,一股突如其來的衝動,或是微妙的渴望嘗試成為不同的人。日常生活中自然的流動不時會喚起成為別人的需求。不論是官僚難題、功能失調的工作環境,還是微妙的家庭事務,都需要仔細管理情感智商和一點角色扮演。在你意識到之前,你可能不得不做一些你不信任的事情。你內心的想法和你的表情可能會產生矛盾,彼此講述完全不同的故事。但是這裡我所指的衝動不僅僅是角色扮演來處理棘手的情況,或者只是想像自己生活在另一個時代、另一個地方或一個新的體制中,而是真正內化一個與你現有身份完全不同的身份。這種逃避也許常常是出於不合邏輯的本能,想要拯救自己,不想成為你所在的地方和自己的那個人。幾乎像是慢慢穿上一個新的角色,像是穿上一件新的外套。下一步,你就會發現這件陌生的外套開始更好地適應自己的形態。它感覺異常地舒適。

你發現自己置身於一個類似精心設計的畫作中。陌生的氣候似乎更加溫和。森林變成了充滿異國情調的烏托邦景象。三角形的多面體可以呈現你想像中的任何顏色。繁茂的松樹變得細長而幽暗。枝幹扭曲而捲曲,水平生長。黑色的森林空氣清新而遙遠。只有一些猴子和女人的聲音才打破了這片沉默的叢林。這種變化的感覺將你帶到了一個新的領域。這種感覺如此解放,以至於你那隱形的夾克慢慢地完全消失了。在你自己選擇的新身份中生活的經驗就像赤身裸體一樣,自由自在,勇敢自然。彷彿你在新的角色中以一種不同尋常的方式變得更加自我意識。你過去只會談論自己絕對確定的事情。現在,在這些變化的茂林之中,你敢於冒險,並意識到自己甚至沒有意識到的能力。以柔和而有力的力量,你可以改變那些你認為需要改變的事情,讓可思考的東西自行形成並具體化。

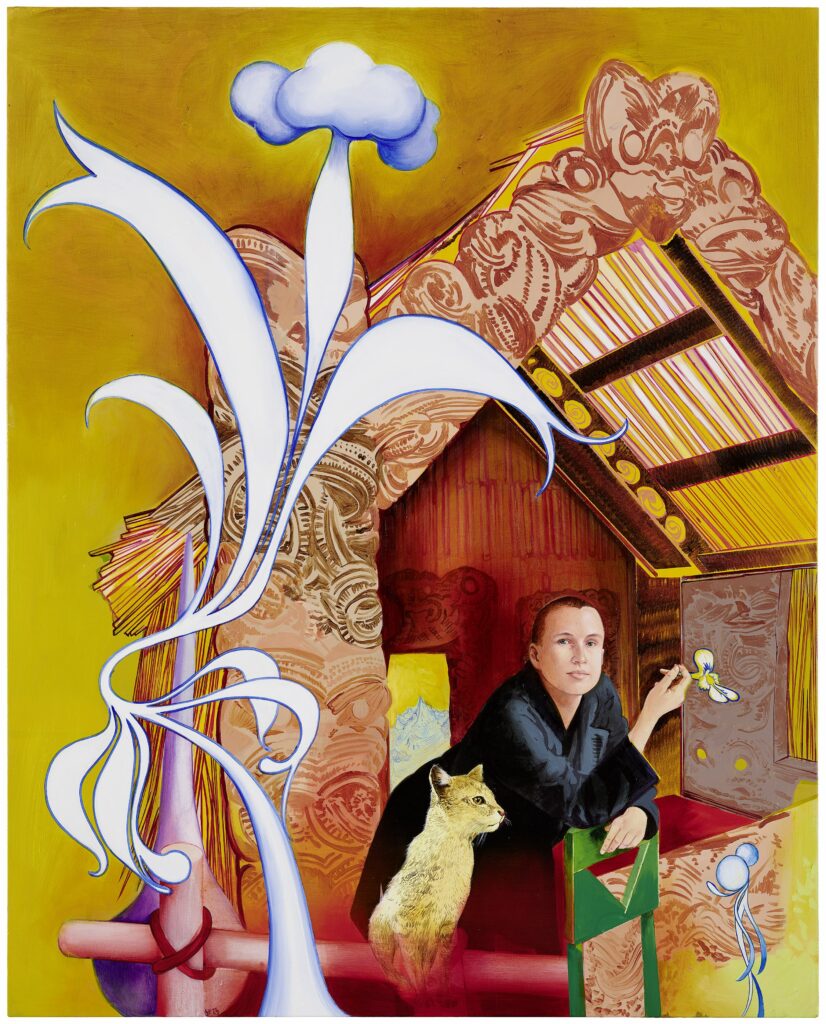

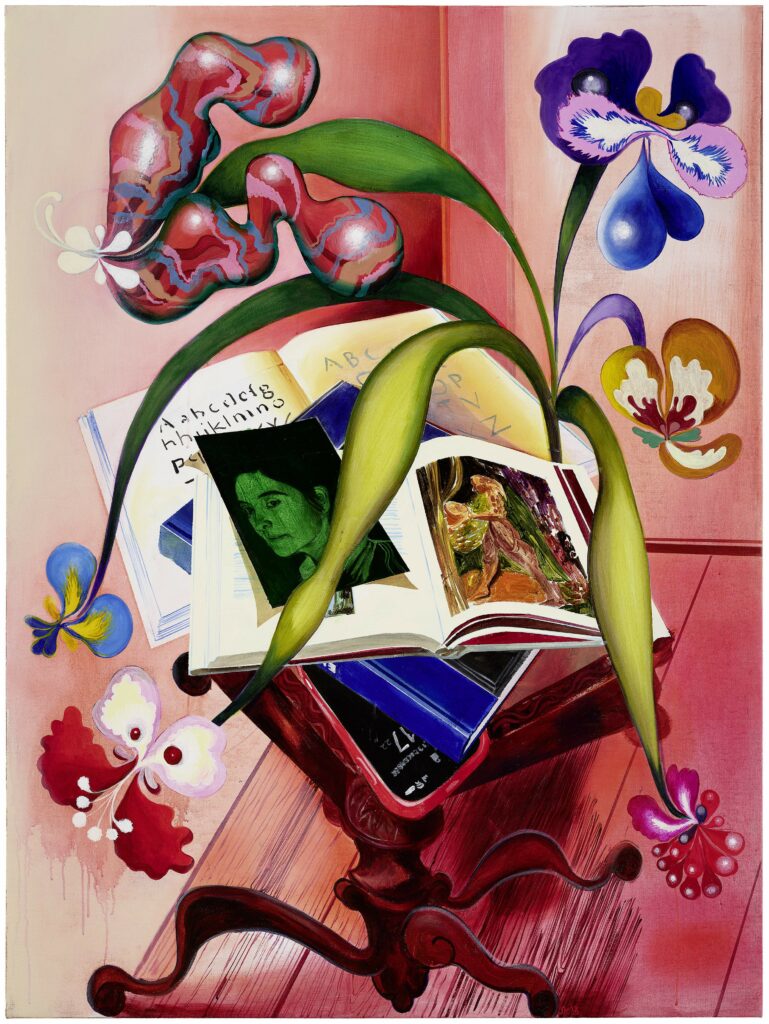

欣賞一幅畫作也可以像試圖成為別人那樣讓人感到有力量。欣賞一幅畫可以激發你內心的另一個人格。如果你站在一幅畫前,讓它觸動你的心靈,這可能是一次改變人生的經歷。如果你願意,一幅有靈魂的畫可以改變你看待世界的方式。當我第一次看到蘇珊.庫恩發人深省的畫作Beastville(2019)時,它對我產生了巨大的影響。 Beastville 啟示並促進了自然、人類和不同物種之間互相關聯的發現,以及尋找新的思考方式——走出傳統和異性戀規範信仰體系的路徑。在看這幅畫時,我首先想到的是由瑪倫·阿德(Maren Ade)編劇和執導的喜劇劇情片《托尼·厄德曼》(Toni Erdmann,2016年),該片集中討論了父女疏遠的主題以及這種情感所帶來的困難。畫作的中心人物,大猴子的毛茸茸的身體,讓人想起電影中父親角色在一場充滿感情的擁抱中穿著古怪、巨大的毛茸茸的服裝的場景。通過創造化身和虛假身份,父親溫弗里德(Winfried)在整個電影中試圖成為另一個人,以便與女兒親近。他的工作狂女兒伊內斯(Ines)全身心地投入到商業諮詢公司的工作中,幾乎沒有時間給自己和家人。因此,溫弗里德發明了一個名為托尼·厄德曼的替代身份,並開始持續地假裝是伊內斯的CEO的生活教練,使他能夠參加與伊內斯相同的活動並經常乾擾她的日常生活。通過成為托尼·厄德曼並成為另一個人,他有效地能夠比在父親角色下更頻繁地與女兒互動。當父親為了接近女兒而通過創造化身和虛假身份時,這種方式雖然尷尬、黑暗和不尋常,但他有機會在身體上靠近女兒,密切觀察她的生活並開始感覺自己是她生活的一部分。特別是那件覆蓋全身,包括面部的蓬亂黑色服裝,給了他完全的匿名性,但同時也讓他成為真正的自己,做他真正想做的事情,受他有些憂鬱和憂傷的內心感覺所驅動(fig. 1)。在一次採訪中,電影的編劇和導演瑪倫·阿德用德國文化背景來描述溫弗里德(Winfried)和伊內斯(Ines)之間的關係,這也可以應用於畫作Beastville的隱含動態。從某種程度上說,它涉及到女性和猴子形象之間的緊張和友誼,既是他們的對立又是他們的一體。

“我也對父女之間的政治衝突感到興趣。我的意思是,他屬於德國非常典型的戰後一代,這一代人非常關注政治,並以溫暖的人類價值觀教育他們的孩子,並讓他們走向外面世界去探索。但是這一代人也相信一個沒有邊界的世界和一個沒有邊界的經濟體系,而現在,他的孩子們必鬚麵對這個結果。現在,他面臨的情況是一切都與他背道而馳。她不再在家了,他對她的世界觀顯得狹隘和幼稚。我只是希望電影能觸及到這種情況。”

父親穿的服裝被稱為“庫克里”(kukeri),這是一種傳統的、令人恐懼的保加利亞服裝,由執行驅逐邪靈儀式的人們穿著。這種服裝非常高,頭部長得醜陋,由長長的黑色毛髮組成,沒有眼睛。

“這些服裝覆蓋了身體的大部分,包括動物形木製面具(有時是雙面的),腰帶上還掛有大鈴鐺。在新年和大齋節前,庫克里會穿著這些服裝,在村莊中行走和跳舞,用他們的服裝和鈴鐺的聲音趕走邪惡的靈魂。人們也相信他們能為村莊帶來好的收成、健康和幸福。”

不同文化都有其相等的庫克里。不僅在巴爾幹、希臘、羅馬尼亞和波圖斯地區,還有其他歐洲國家。例如,安納托利亞土耳其神話中講述了一個名為Gulyabani的巨型毛茸茸的怪物。在德國南部,有幾種狂歡節傳統,包括恐怖的服裝。在瑞士阿爾卑斯山區的Lötschental和Appenzell地區,有特別恐怖的狂歡節服裝,與庫克里的想法和風格非常相似。這是一個基於異教、基督教前或伊斯蘭前的信仰的共享文化。在保加利亞的山區,身穿庫克里服裝的人們成群結隊地移動、跳舞,並進入村莊里的人家,他們還會進行集體的儀式舞蹈。由於庫克里沒有眼睛,非常黑暗和巨大,他們與其他村民的互動不可避免地引起恐懼。這個想法是體驗一種恐懼感,幾乎到了震驚的地步,宣洩緊接而來。

就像穿著庫克里服裝的庫恩,或者說實際上變成了一個既可怕又溫和的猴子形象。就像托尼·艾德曼(Toni Erdmann)穿著尷尬的庫克里服裝,被他的女兒意外地熱情擁抱,從而與她經歷了一個特殊的時刻,庫恩也在通過轉變自己,與她的繪畫實踐和她所描繪的世界建立了一種親密的關係。通過在猴子胸膛上畫她的頭,她實際上已經變成了別的什麼。她穿著一件巨大的猴子服裝嗎?她背著猴子嗎?還是她試圖逃離猴子的內部,就像試圖逃離一種情境?猴子在生她嗎?猴子用優雅的方式在心中承載她嗎?當這些問題在我的腦海中浮現時,我正看著這幅畫,這使我感到愉悅的困惑。我思忖著。

我確定了一件事情:猴子和畫家之間既沒有衝突也沒有競爭。他們之間有友誼,他們是一體的,互相支持。猴子可能把畫筆遞給她,而不是從她手中奪走它。他們也許正在一起創作,互相談論共同的計劃,是否應該在森林裡散步,還是繼續作畫。然後是猴子用左手做出的手勢,食指指向黑暗的森林,未知的誘惑,未來的吸引。或者它正在伸手去觸摸柔和地爬行在它們背上的昆蟲。猴子的食指與松樹枝相同:食指與樹非常接近,幾乎接觸在一起,就像畫家和猴子一樣。乍一看似乎矛盾的事物最終證明是相互滋養的元素。雖然一開始給人一種對自然的威脅的印象,但穿過樹木的幾何結構似乎與景觀相容。在沒有陽光或月光的情況下,它們似乎是場景中唯一產生溫暖色彩的東西。女人、猴子、樹木、植物和建築之間存在著關懷、同情和集體的感覺。兩個女人交織在一起奔跑,彼此並肩但卻在彼此之上,攜帶著另一個猴子。也許,庫恩背負的猴子變得越來越重,在沿途中終於幾乎完全覆蓋了畫家。最讓我印象深刻的是關於他們角色的模棱兩可性——誰在為誰服務?兩個女人從火災、獵人、污染以及其他種種人為的危害和災難中拯救這隻猴子。她們共同尋找在這個受損的星球上生存的方法。或者她們正在帶著背上的猴子向前進步和未來的成就奔跑?這些未解決的、開放式的問題潛藏在畫中,讓觀者感到一種奇怪的感覺。這種神秘感覺異常愉悅。這種心境貫穿了整幅畫的性格。儘管它既陰森又神秘,但絕不是悲觀的。

受到她對自然的熱愛和對藝術博物館和自然歷史博物館的興趣影響,庫恩對文化遺產和多元文化動態深感著迷,包括殖民地背景下的動物認知和展示政治。在西歐博物館的民族學和自然歷史藏品中,收藏了許多從全球南方殖民地時期收集的植物和動物標本。 2018年,德國博物館協會發布了一份PDF格式的在線指南,標題為《處理殖民地背景下收藏品的指南》,從歐洲中心主義的角度,詳細科學地解釋了殖民主義在博物館藏品背景下所帶來的遺產,以及如何有意識和負責任地處理這些藏品的方法。儘管這份旨在善意的指南引起了人們對這類現有藏品的問題性質的關注,並試圖激發新的處理方式,但它在試圖成為多元化方面失敗了。編輯團隊缺乏來自德國本土以及全球南方、對展覽實踐中的後殖民主義問題感興趣的學者和策展人的必要專業知識。就在上週,德國文化和媒體國務大臣莫妮卡·格呂特斯發表了關於這個問題的公開聲明:“曾經是通過暴力和強制徵用的,無法在今天的良心下被視為合法的收購。”

目前在德國,正在進行一場激烈的辯論,關於是否應該將這些來自前德國殖民地和其他地方的文化物品歸還其原產地。考慮到這個問題在博物館中的相對近期認可,值得注意的是蘇珊.庫恩 在這方面的預見性,因為她幾年前就已經關注到這個話題。她已經用歷史上具有爭議的收藏中的題材進行繪畫一段時間了,因此將這個歷史融入她的畫作中。她沒有直接處理這個主題或描繪周圍的問題,而是使用它的有爭議的本質作為產生緊張或提出問題的工具。

繪畫《Beastville》中沉思的猴子作為填充動物在維也納自然歷史博物館展出。雖然我不知道這件特定的文物是什麼時候成為博物館藏品的一部分的,但我們知道,這類物品通常具有殖民地時期的歷史。 Beastville畫作中的巨型猴子形像是根據庫恩2015年在2015年在哥廷根動物博物館看到的一隻標本動物。藝術家選擇這只迷人的猿猴成為畫作的共同主題,這種黑須短尾猴,這是一種有鬍子的粗尾猿,是一種長須猴中的五種僅存猴種之一,分佈在巴西東北部。這種瀕危物種不僅美麗,而且聰明。它輕柔地握著畫筆,與人類一同作畫,這給我們帶來了啟示。黑須短尾猴的屬名是僧面猴Chiropotes(satanas),意思是“飲水者”,因為人們觀察到牠們使用手將水舀入嘴裡。牠們知道如何有目的性的使用手。黑須短尾猴還會用尾巴抓取東西。不幸的是,像許多其他動物一樣,如大象、老虎、犀牛和海龜,牠們也引起了獵人的注意被獵捕作為野味,而牠們長而厚的尾巴則被用作清掃工具。畫中描繪的這種聰明、迷人的黑須短尾猴,在過去也曾被獵殺,最終作為來自異國他鄉的動物標本在博物館公開展出。我仔細觀察黑須短尾猴的眼睛,察覺到一種恐懼與好奇心。接著,我轉向觀看蘇珊·庫恩的頭部和她的平靜眼神,透露出自信但同時帶有懷疑。每一雙眼睛都帶有一種懷疑的神情。觀看時,很難不想起達爾文的進化論。人類和類人猿有著密切的關係,我們共享同一個祖先。經過數百萬年的演化,這兩個物種已經分化成現代的智人和各種類人猿。然而,有神論者和保守派不同意進化科學,這在歷史上一直是不一致的。庫恩將自己和黑須短尾猴描繪成一個身體,評論了這兩個物種之間的密切關係。因此Beastville間接地提到了圍繞進化論的辯論。

Beastville所涉及的另一個主題涉及女性在工作場所和藝術領域內的角色和地位,儘管不是因為庫恩是女性藝術家,而是因為這幅畫聚焦於女性:她自己和另外兩個女性,可能是同伴、姐妹、女兒、同事、鄰居、陌生人、其他女性藝術家或文化領域中的女性。她們都試圖協同行動,肩負著重擔,並可能在某個時候必須成為另一個人以求生存。當考慮到如何成為一位女性藝術家時,Chus Martínez最近一篇有力的文章令人想起:

“近幾十年來,我們看到了人們對女性在職場和社會中面臨挑戰的認識增強,然而女性的處境並不能被描述為光明。… 在畫廊中,女性藝術家的作品售價至少比男性藝術家低20%,在拍賣會上,這種差距甚至達到50%。女性在市場中佔少數,並且她們獲得參加展覽的邀請要少得多 -更難以參加展覽、成為影響範圍的一部分。因此,我們似乎有責任制定措施來迫使局勢改變:如果我們無法監管市場,那麼我們肯定可以監管公共空間。對於董事會和讚助商也是如此。你無法控制董事會的想法,但改革董事會以符合民主、平等社會的價值觀是完全可能的。像瑞典這樣的國家率先規定,董事會和理事會中必須有50%的女性代表。我們不能指望在不改變行使這些權利的基準的情況下實現我們的權利。我們應該爭取新的政策和措施,而不僅僅是權利。藝術界非常保守;儘管它對左翼活動持有同情態度,但幾乎可以稱其為反動”

我们知道并经历了作为一名女艺术家和文化工作者的挑战,无论何时何地,我们都必须解决系统性的不平等问题。因此,对于任何愿意冒险进入画作、与猴子结盟并敢于成为自己而不失去内心声音的人来说,观看Beastville都是极具启发意义的。

Didem Yazıcı

Didem Yazıcı是一位策展人和作家,出生於土耳其,現居德國。她曾作為新藝術博物館策展團隊成員(2015-2016)策劃展覽、視頻節目,並參與編輯展覽目錄。於2016年擔任開羅歌德學院策展人駐場,並參加第11屆上海雙年展的基礎策展計劃。此前,她在斯圖加特藝術家之家擔任研究員和客座策展人,並作為項目助理參與了2012年至2013年的第13屆卡塞爾文獻展。最近,她在巴登藝術協會工作(2017-2018),共同策劃展覽,並負責構思和實現該機構200週年紀念活動。

Daring To Become Someone Else in the Land of Beastville

By Didem Yazıcı

“How will you go about finding that thing the nature of which is totally unknown to you?‹ (Plato) The things we want are transformative, and we don’t know or only think we know what is on the other side of that transformation. Love, wisdom, grace, inspiration – how do you go about finding these things that are in some ways about extending the boundaries of the self into unknown territory, about becoming someone else?”- Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide To Getting Lost (2005)

Whenever you are holding a book in your hand and reading, visiting an exhibition and looking at a painting or simply walking down the street, in or out of your comfort zone, does it ever cross your mind to become someone else? An ambivalent instinct, a sudden rush or the subtle urge to try to be a different person. Once in a while the natural flow of everyday life conjures up the need to become someone else. Be it a bureaucratic difficulty, a dysfunctional working environment or a delicate family matter, careful management of emotional intelligence and a bit of role-playing are in order. Before you know it, you may have to do something that you do not believe in. Your inner heart and your face may be at odds with one another, each telling completely different stories. But this impulse I am referring to here is more than that. Not just role-playing to manage a tricky situation or simply imagining living in a different time, another place or a new dispensation, but actually internalizing a completely different identity to the one you have. An escape perhaps that is often illogically driven by instincts to save yourself from who you are and where you do not want to be. Almost like slowly dressing yourself up in a new character, like donning a new jacket. The next thing you know, this strange, alien jacket starts to cleave to its mold a little better. It feels oddly comfortable.

You find yourself in an otherworldly composition just like a well thought-out painting. Unfamiliar climates seem more amenable. Forests become eclectic, utopian landscapes. Triangular polyhedrons appear in any color you care to dream up. Proliferating pine trees become elongated and tenebrous. Branches are gnarled and curly, growing horizontally. Black forest air freshens and grows more distant. The jungle is silent but for the sound made by a few monkeys and women. This feeling of change transports you to a new realm. It is so liberating that your invisible jacket gradually begins to fade away completely. The experience of living in your new self-chosen identity is akin to being naked. It is liberating. It is courageous. It is natural. As though you are becoming more self aware in an unusual way in your new persona. You only used to speak about things you are absolutely sure of. Now in this thicket of changes, you embrace risk-taking and become aware of abilities you didn’t even know you had. With a soft, gentle power you can transform things that you think need to be transformed and allow the thinkable itself to take shape, to materialize.

Looking at a painting can be as empowering as trying to become someone else. Looking at a painting can bring out another person in you. If you stand in front of a painting and let it speak to your heart, it can be a life-changing experience. A painting with a spirit can change the way you perceive the world if you let it. When I saw Susanne Kühn’s thought-provoking painting Beastville (2019) for the first time, it had a huge impact on me. Beastville initiates and facilitates the discovery of an interconnectedness between nature, humans and different species, as well as finding new ways of thinking – pathways out of conventional and heteronormative belief systems. The first thing that sprang to mind while looking at the painting was the beautiful and heartbreakingly poignant scene from the comedic drama Toni Erdmann (2016) written and directed by Maren Ade, focusing on the theme of father-daughter estrangement and the difficult emotions this can engender. The central figure of the painting, the large hairy body of the monkey, recalls the outrageous, gigantic woolly costume that the father character wears toward the end of the movie in a scene in which father and daughter spontaneously enjoy a lingering and heartfelt embrace. Through creating alter egos and fake identities, Winfried, the father, is trying to be someone else throughout the movie in order to be close to his daughter. Dedicating herself fully to her working life in a business consultancy, his workaholic daughter Ines barely has time for herself and her family. As a result, Winfried invents an alternative identity called Toni Erdmann and initiates the sustained pretense of being the life coach of Ines’s CEO, enabling him to attend the same events as Ines and regularly intrude upon her daily life. By becoming Toni Erdmann and being someone else, he is effectively able to interact with his daughter more frequently than in his role as her father. Although it is an awkward, dark and unusual way to pursue this aim, he gets the chance to be close to her physically, observe her life closely and begin to feel part of it. Particularly the shaggy black costume that covers his entire body, including his face, affords him complete anonymity, but at the same time enables him to be truly himself, and do what he really wants to do, driven by his somewhat saturnine and melancholic inner feelings (fig. 1). In an interview, the writer-director of the movie, Maren Ade, describes the relationship between Winfried and Ines in terms of a specifically German cultural context, which could also be applied to the hidden dynamics of the painting, Beastville. In a way, it refers to the tension and friendship between the women and monkey figures. Being someone or something else, being against them and one with them in a paradoxical sense.

“I was also interested to have that political conflict between the father and the daughter. I mean, he belongs to a very typical generation in Germany, the post-war generation that was very political and raised their children with a lot of warm human values and then sent them out into the world to be curious. But that generation also believed in this world without borders and also in an economy without borders but it’s their children who have to deal with it. Now, he’s confronted with that result in a way that everything turned against him. She’s not home anymore and his view of the world for her is constricted and naive. I just wanted the film to touch that situation.”

The costume that the father wears is called a kukeri, a traditional and terrifying Bulgarian costume worn by people who perform ritual traditions intended to ward off evil spirits. It is very tall with a grotesquely elongated, eyeless head made entirely of long, black shaggy hair.

“The costumes cover most of the body and include decorated wooden masks of animals (sometimes double- faced) and large bells attached to the belt. Around New Year and before Lent, the kukeri walk and dance through villages to scare away evil spirits with their costumes and the sound of their bells. They are also believed to provide a good harvest, health, and happiness to the village during the year.”

Different cultures have their equivalent kukeri. Not only in the Balkans, Greece, Romania and the Pontus region, but also in other European countries. For example, Anatolian Turkish myths tell of a monstrous, hirsute giant called Gulyabani. In Southern Germany, there are several carnival traditions that include frightening costumes. In Lötschental in the Swiss Alps and in Appenzell, there are particularly frightening carnival costumes that closely resemble the idea and style of the kukeri. It is a shared culture based on paganistic, pre-Christian or pre-Islamic beliefs. In the mountains of Bulgaria, people wearing kukeri costumes move around in groups, dancing and entering people’s houses in the villages where they also perform ritual group dances. Since the kukeri are eyeless, very dark and enormous, their interaction with the other villagers inevitably induces fear. The idea is to experience a sense of dread, almost to the point of shock, followed by catharsis.

As though wearing a kukeri, Kühn has donned a costume or has actually morphed into a monkey figure that is frightening yet at the same time benign. Just like Toni Erdmann, who is given an unexpected, warm and dramatic hug from his daughter in his awkward kukeri costume and thus experiences a special moment with her, Kühn is also transforming herself to achieve an intimate relationship with her practice and the world she is painting. By painting her head on the chest of a monkey, she has literally become something else. Is she wearing a giant monkey costume? Is she carrying the monkey on her back? Or is she trying to escape from being inside the monkey, like trying to leave a situation? Is the monkey giving birth to her? Is the monkey carrying her in its heart with grace? I was looking at the painting while all these questions surfaced in my mind resulting in a state of pleasant confusion. I took a break.

I was sure of one thing: there is neither conflict nor competition between the monkey and the painter. There is friendship between them. They are one and they support each other. The monkey may be passing the paintbrush to her hand instead of taking it away from her. They may be painting together collectively as they talk to one another about shared plans, whether they should take a walk in the forest, or just keep painting. Then there is the gesture the monkey is making with its left hand, its index finger pointing toward the dark forest, the seductive unknown, the lure of the future. Or perhaps it is reaching out to the insect that is gently travelling up its/their back. The monkey’s index finger is identical to the branch of the pine tree: the finger is so close to the tree – they are nearly touching, almost fusing in a similar way to the artist and the monkey. The things that seem to be contradictory at first glance turn out to be mutually nurturing elements. Although they initially give the impression of being a threat to nature, the geometrical structures running through the trees seem to be compatible with the scenery. In the absence of sunlight or moonlight, they appear to be the only things that generate warm color in the scene. A sense of care, compassion and collectivity exists between the women, monkeys, trees, plants, and structures. The interwoven bodies of two women who are running side by side yet on top of each other are carrying another monkey. Maybe the monkey Kühn is carrying on her back became so heavy along the way that it has finally almost totally enveloped the painter. What struck me the most is the ambivalence regarding their roles – who is serving whom? The two women are rescuing the monkey from fire, hunters, pollution, indeed, from all manner of anthropogenic hazards and disaster. They are collectively searching for ways of living on a damaged planet. Or they are running toward progress and future achievements aided by the monkey on their backs? These unresolved, open questions embedded in the painting leave the viewer with a strange feeling. A kind of mystery that feels unusually pleasant. This state of mind informs the character of the painting overall. Although it is both tenebrous and mysterious, it by no means pessimistic.

Driven by her passion for nature and a long-standing interest in both museums of art and natural history museums, Kühn is fascinated by cultural legacies and dynamics in a plural sense, including the colonial context, animal cognition, and the politics of display. Several botanical and zoological items collected in colonial times from the Global South are displayed in ethnological and natural history collections in Western European museums. In 2018, the German Museums Association published an online guide in PDF-format titled Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts, painstakingly and scientifically explaining – from a Eurocentric point of view – the ABCs of colonialism’s legacy in the context of museum collections, as well as offering ways to work consciously and responsibly with these collections. Whereas this well-intended guide raises awareness regarding the problematic nature of existing collections of this kind and tries to inspire new ways of working with them, it fails in its attempt to be pluralistic. The editorial team lacks the necessary expertise from Germany- based academics and curators from the Global South with an interest in postcolonial issues in relation to exhibition praxis. Only last week, the German Minister of State for Culture and Media, Monika Grütters made a public statement on this issue: »What was once appropriated using violence and coercion cannot, in all good conscience, be regarded as a lawful acquisition in this day and age.«3

In Germany at the moment, there is a heated debate in progress regarding the question of whether or not these cultural objects from former German colonies and elsewhere should be restored to their countries of origin. Considering the relatively recent recognition of this problem in the context of the museum, it is worth noting Susanne Kühn’s prescience in this regard, as she had already picked up on the topic some years ago. She has been painting historically-charged motifs from collections of this kind for some time now, and has thus been incorporating this history into her paintings; she doesn’t deal with the theme directly or illustrate the problematic issues surrounding it, but uses its controversial nature as a tool for generating tension or to raise questions about the problem per se.

The contemplative monkey in the painting Beastville is exhibited as a stuffed animal in the Museum of Natural History in Vienna. Although I do not know exactly when this specific artifact became part of the museum collection, we do know that when these kinds of objects are old, they often date from colonial times. The giant monkey figure in the painting Beastville is based on a stuffed animal that Kühn saw in the Zoological Museum in Göttingen in 2015. This charming simian that the artist has chosen to be her co-subject in the painting is indeed quite special, namely the black bearded saki, which is a species of bearded saki, one of five remaining monkeys of their kind and indigenous to parts of north- eastern Brazil. This critically endangered species is not only beautiful, but also intelligent. Its ability to hold the brush gently in its hands and the collective act of painting together tell us something. The genus name for the black bearded saki is Chiropotes (satanas), meaning 【hand-drinker】as they have been observed using their hands as ladles for scooping water into their mouths. They know how to use their hands purposefully. Black bearded sakis also use their tails to grasp things. Unfortunately, like so many other animals, such as elephants, tigers, rhinoceros, and sea turtles, they too have attracted the attention of hunters. They are hunted for bushmeat in particular, whereas their long thick tails are used as dusters. This intelligent and charming-looking bearded saki depicted in the painting, was also hunted in former times, in its case ending up on public display in a museum as a taxidermied exhibit from exotic, distant lands. I paid close attention to its eyes, and noticed a sense of fear and curiosity. I then looked at Susanne Kühn’s head and her calm eyes that convey self-assuredness yet skepticism at the same time. Each set of eyes has a skeptical look about it. When viewing them, it is hard not to think of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution. Humans and apes are closely related. We both share a common ancestor. Over the course of millions of years, these two species have diverged, resulting in what we now observe as the modern Homo sapiens and various species of apes. On the other hand, theists and conservatives disagree with evolutionary science, which has always been consistent throughout history. By painting herself and the black bearded saki as one body, Kühn is commenting on the closeness between the two species. Thus, Beastville is subtly referencing the debate surrounding evolution.

Another theme that Beastville raises relates to the role and position of women in the workplace and within the art context, though not because Kühn is a female artist, but because the painting is focusing on women: herself and two other women, possible companions, sisters, daughters, colleagues, neighbors, strangers, other women artists, or women in the cultural field. All of them are trying to act in concert, they carry the burden on their shoulders, and probably have to be someone else for part of their time in order to survive. When considering what it means to be a woman artist today, Chus Martínez’s recent, powerful article springs to mind:

“In recent decades we have seen an increase in the awareness of the challenges women face in the workplace and in society at large, yet the situation for women cannot be described as bright. … In galleries, art by women sells for at least 20 percent less than art by men, and in auctions this disparity reaches 50 percent. Women are a minority in the market, and they receive far fewer invitations to participate in exhibitions – to be part of the spheres of influence. So, it seems that it is our duty to create measures to force the situation to change: if we cannot regulate the market, we can certainly regulate public spaces. The same goes for boards and sponsors. You cannot control what a board thinks, but reforming the boards to match the values of a democratic, equal society is entirely possible. Countries like Sweden have taken the lead in making it mandatory to have 50 percent representation of women on boards and councils. We cannot expect to realize our rights without changing the ›nests‹ in which these rights are exercised. We should fight for new policies and measures, not only rights. The art world is very conservative; one could almost call it reactionary, despite its sympathy for left-leaning activism.”

Knowing and experiencing the challenges of being a woman artist and cultural worker, we must address systemic inequalities whenever and wherever we encounter them. Therefore, looking at Beastville is immensely empowering for anyone who is willing to take the risk and step into the painting, enter into alliances with monkeys and dare to be someone else without losing one’s inner voice.

Didem Yazıcı

Didem Yazıcı is a curator and writer, born in Turkey and based in Germany. As a member of the curatorial team of the Museum für Neue Kunst, Freiburg (2015 – 16), she curated exhibitions, video programs of Schau_Raum and co-edited exhibition catalogues. She was curator-in-residence at the Goethe Institute Cairo in 2016 and participated in the Infra-Curatorial of the 11th Shanghai Biennale. Previously, she was a researcher and guest curator at the Künstlerhaus Stuttgart and worked at documenta (13) as a project assistant (2012 – 13). Recently, she worked at the Badischer Kunstverein (2017 – 18) where she co-curated exhibitions and worked on conceptualizing and realizing the 200th anniversary programme.

展出作品

Susanne Kühn

(Germany , b. 1969)

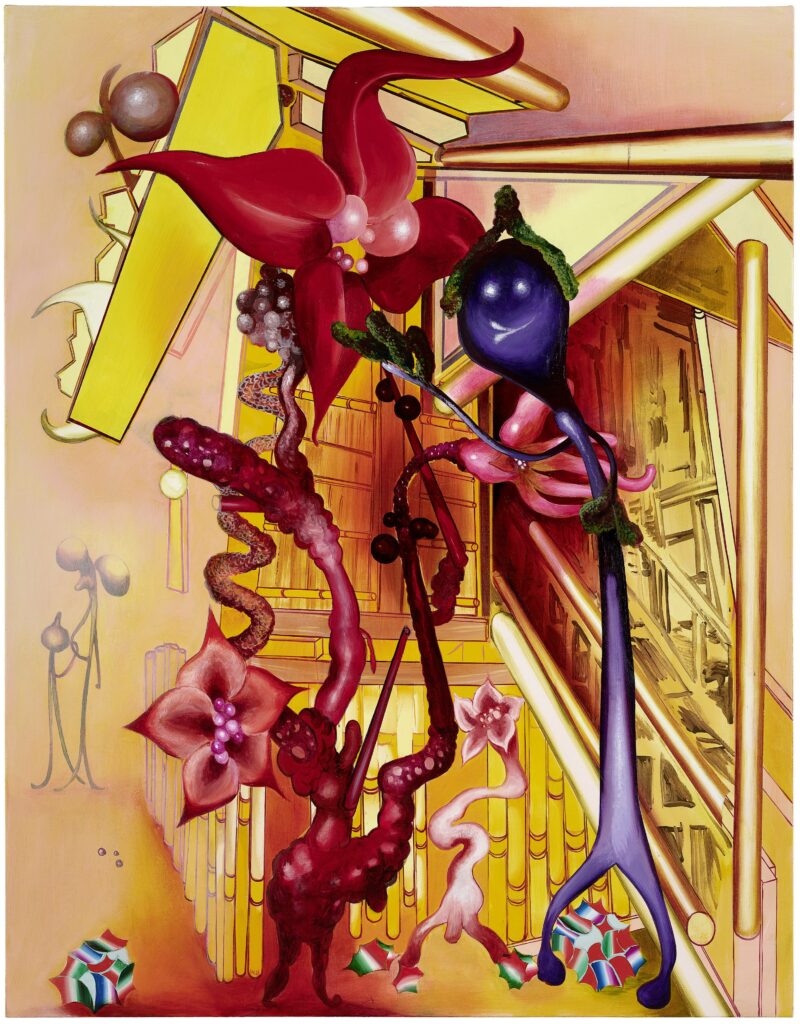

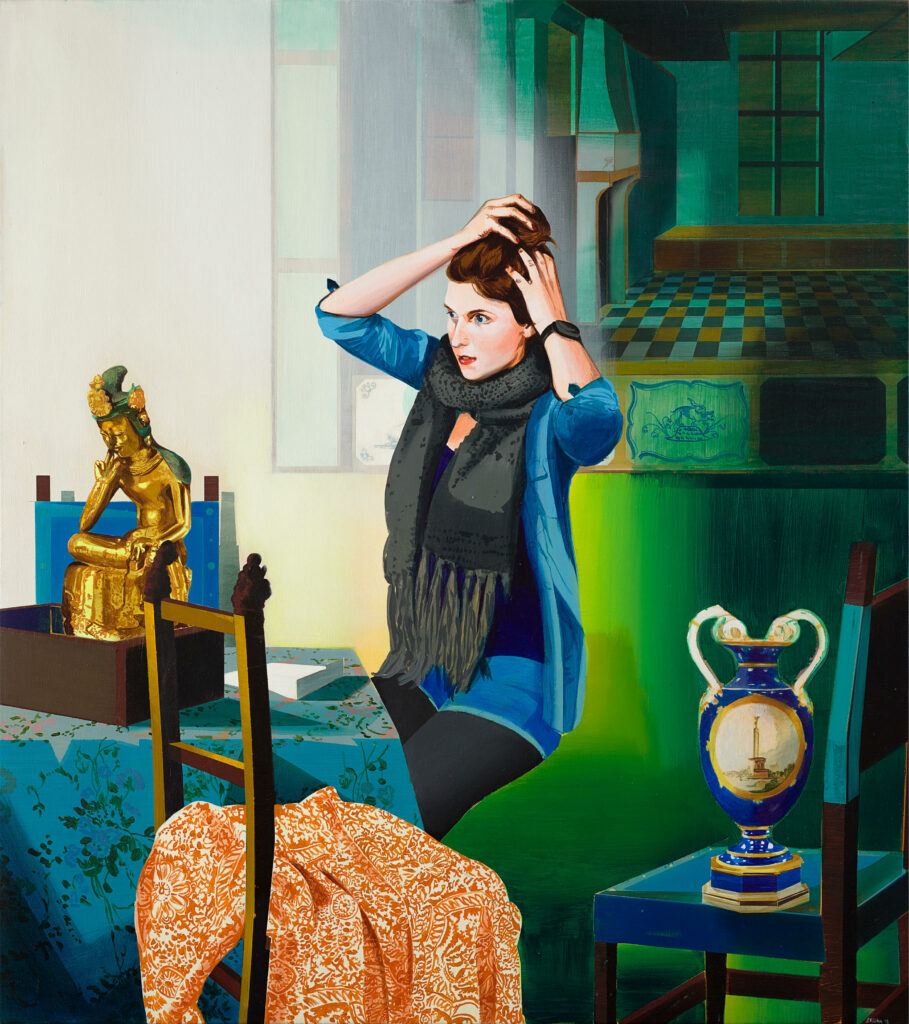

苏珊・库恩 Susanne Kühn (德国, b.1969),目前创作及居住于德国弗莱堡及纽伦堡。拥有莱比锡视觉艺术学院绘画与版画艺术硕士学位,并曾获哈佛大学拉德克利夫高等研究院(Harvard University Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies)奖学金。库恩Kühn深入研究欧洲艺术史,深受传统浪漫主义启发,她将绘画传统欧洲山水画的元素、文艺复兴视角、日本木刻版画甚至流行文化与现代抽象的各种绘画语言并置,创造了一种深思熟虑、扭曲的视角和抽象感。曾多次参与国际展览,包括德国策勒艺术博物馆、弗莱堡当代艺术博物馆、美国丹佛当代艺术博物馆、纽约根特Art Omi国际艺术组织等,作品由UBS艺术收藏、美国堪萨斯城肯珀当代艺术博物馆、哈佛大学施瓦茨艺术收藏馆、德国弗里德布尔达私人博物馆、弗莱堡当代艺术博物馆、德意志联邦银行、英国Zabludowicz 艺术收藏及最大莱比锡学派收藏Sammlung der Sparkasse Leipzig 等机构永久收藏。

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2022 Susanne Kühn, Profliferation – Vasa, Auginella & other Sprouts, Galerie für Gegenwartskunst, E-Werk Freiburg, Germany

2021 Susanne Kühn. Malerei OnSite, Kunstmuseum Celle mit Sammlung Robert Simon, Germany

2021 FLASH – Susanne Kühn, Beck & Eggeling Düsseldorf, Germany

2020 BANK – Inessa Hansch + Susanne Kühn, Augustinermuseum Freiburg, Germany

2019 BOSCH & KÜHN, Gemäldegalerie der Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien, Austria

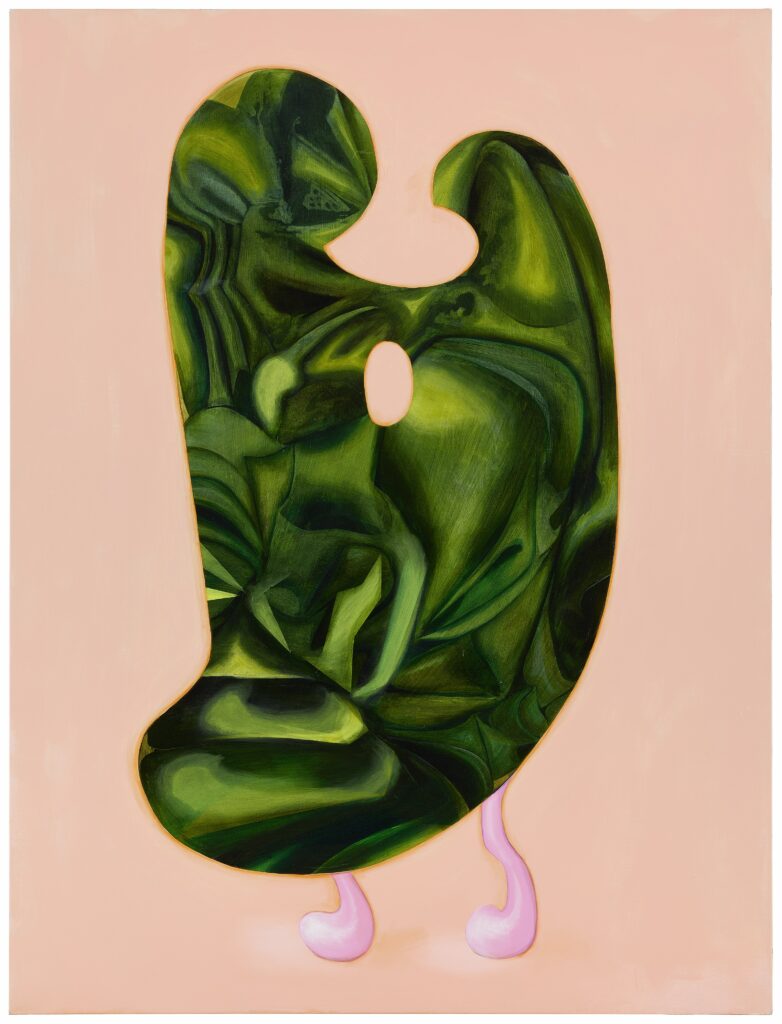

2019 “PALETTE”, Beck & Eggeling Vienna, Austria

2017 Susanne Kühn, viennacontemporary art fair, Beck & Eggeling, Vienna, Austria

2017 Susanne Kühn, SPAZIERGÄNGE & andere STORIES, MNK im Haus der Graphischen Sammlung, Augustinermuseum Freiburg, Germany

2016 Susanne Kühn, ArtOMI International Arts Center, Ghent, New York, USA

2015 BANK, Galerie Kleindienst Leipzig, Germany

2014 Susanne Kühn – World of Wild Animals, Beck&Eggeling Düsseldorf, Germany

2012 15 Drawings, Sala Uno, Contemporary Arts Center Rome, Italy

2011 Susanne Kühn – GARDEN EDEN, Haunch of Venison, London, UK

2010 Susanne Kühn, Kunstverein Lippe, Germany

2010 Susanne Kühn – Study of Landscape, Robert Goff Gallery, New York, USA

2009 Susanne Kühn, Forum Kunst, Rottweil, Germany

2008 Susanne Kühn, Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, USA

2008 Susanne Kühn, Goff+Rosenthal Berlin, Germany

2007 Susanne Kühn, Kunstverein Freiburg, Germany

2007 New Paintings, Goff+Rosenthal, New York, USA

2007 Drawings, Fred (London) Ltd, Leipzig, Germany

2006 Paintings, Galerie Echolot, Berlin, Germany

2005 Susanne Kühn, Fred (London) Ltd, London, UK

2005 Susanne Kühn, Goff+Rosenthal, New York, USA

2004 Susanne Kühn, Galerie Echolot, Berlin, Germany

2004 Malerei + Zeichnung, Galerie Kleindienst, Leipzig, Germany

2003 Works on Paper, Bill Maynes Gallery, New York, USA

2002 Journey, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, USA

2001 Recent Works, Bill Maynes Gallery, New York, USA

2000 Drawings, Bill Maynes Gallery, New York, USA

2000 Recent Paintings, Samek Art Gallery, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, USA

2000 Drawings, German Consulate House, New York, USA

1999 Paintings, Bill Maynes Gallery, New York, USA

1997 Landscapes, Beck & Eggeling, Leipzig, Germany

Collections

Busch-Reisinger Museum Collection / Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA, USA

University of Colorado Art Museum, Boulder, CO, USA

Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, MO, USA

Knoxville Museum of Art, Knoxville, TN, USA

Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

FRAC Alsace, France

Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden, Germany

Kunstmuseum Celle mit Sammlung Robert Simon, Celle, Germany

Sammlung der Deutschen Bundesbank, Germany

Sammlung Alison and Peter W. Klein, Germany

Museum für Neue Kunst, Freiburg, Germany

Sammlung Sachsen Bank, Germany

Sammlung der Sparkasse Leipzig, Germany

UBS Art Collection, Switzerland

The Graphic Collection of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, Austria

Picture Gallery of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, Austria

Zabludowicz Art Trust

‘伏笔‘ Foreshadow – 鲁普雷希特·冯·考夫曼 Ruprecht von Kaufmann & 苏珊·库恩Susanne Kühn 双人展

展期

2023.5.20-7.30

Bluerider ART, 上海·外滩

周二-周日 10am-7pm

上海黄浦区四川中路 133 号

免费参观

当期展览