看展览 Exhibition

预告片 Trailer

艺术家访谈影片

导览影片

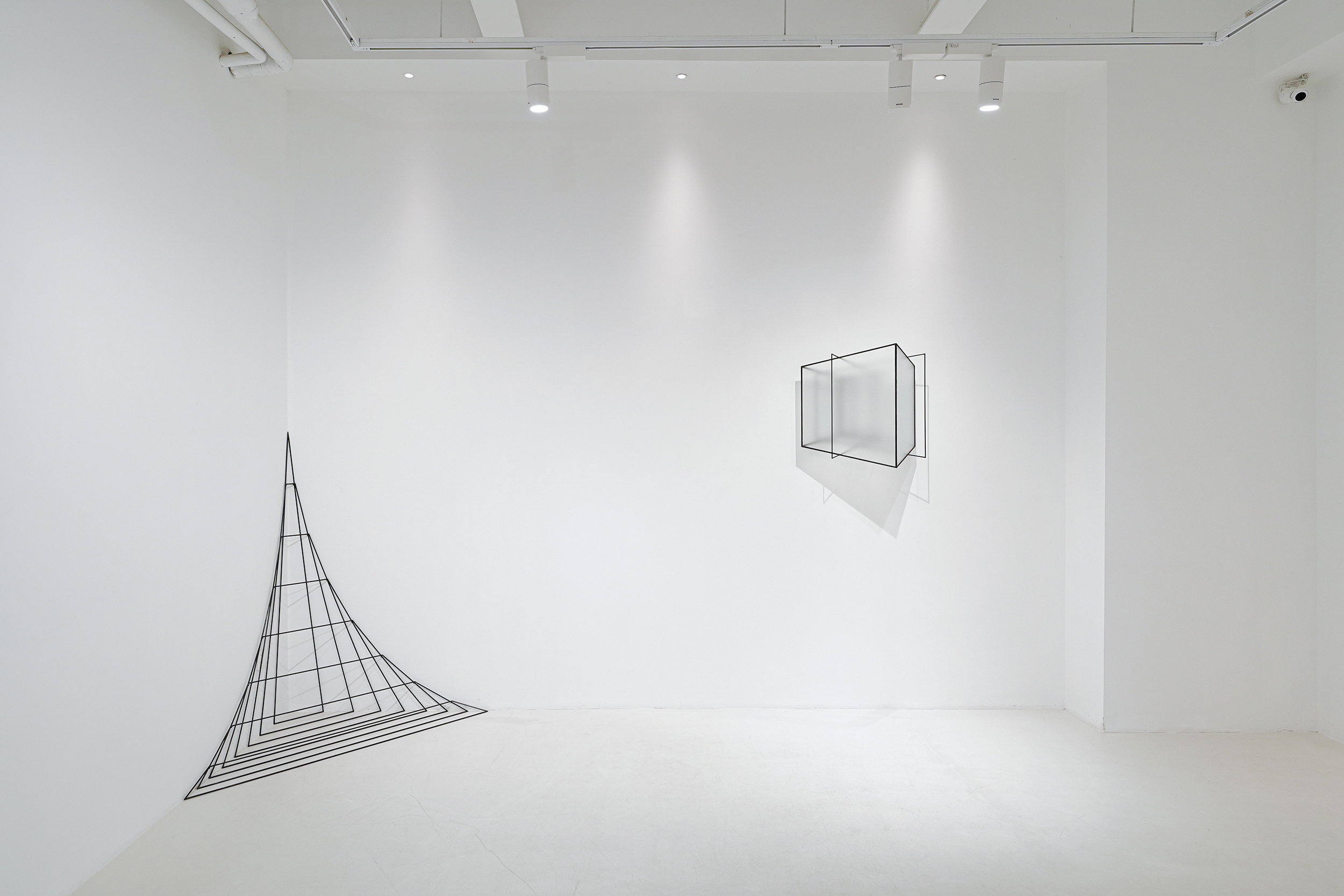

展场照片

看展Tips提示:

☝️寻找那条沿着展埸1.65米高,看不见的隐形水平线、和消失点

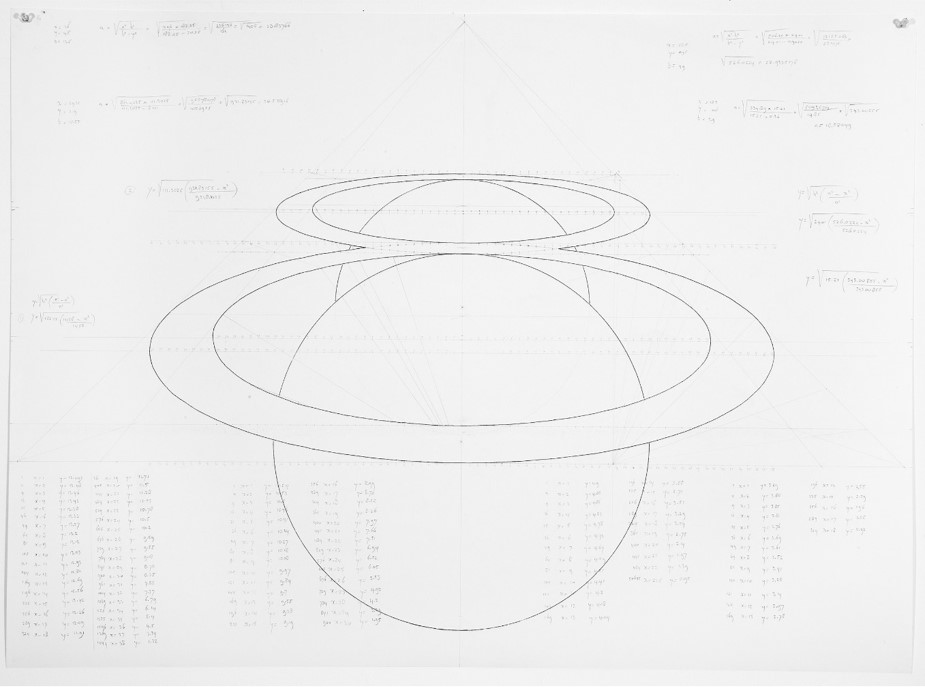

✌️别忘了欣赏那些密密麻麻、数学运算的过程手稿

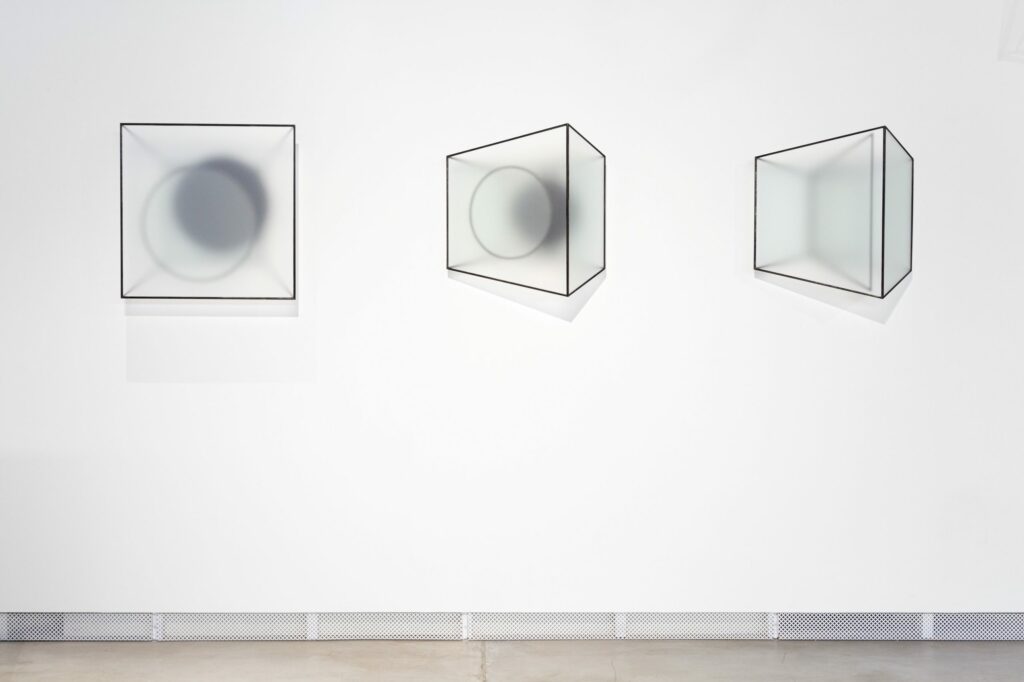

👌对着窗型作品缓缓地左右走动,发掘雾里的风景忽隐忽现

p.s. 视觉高度不够1.65米高,可以柜台借小矮凳

开幕日现场影片

开幕日照片

‘1.65’ — 雷诺·奥德霍恩Reinoud Oudshoorn中国首个展

Bluerider ART 上海・外滩

2022.10.29-12.25

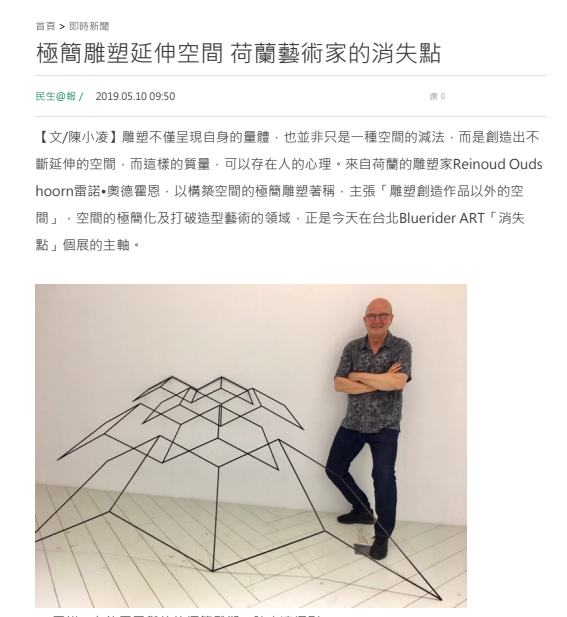

雷诺・奥德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn(荷兰,b.1953) 荷兰阿特利尔63学院艺术硕士(MFA, The Ateliers 63 Haarlem),阿尔特兹艺术学士(BFA, AKI School of Arts, Enschede),现居住创作于荷兰阿姆斯特丹,曾执教于荷兰皇家艺术学院。雷诺・奥德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn以构筑空间的极简雕塑著称,认为解决问题是一切创作根源。统一设在1.65M高的灭点(Vanishing Point),从此开启每件作品的生命里程,透过单色极简材质的细腻叙述,点线面多点交错灭点的独特语言风格,实现其一贯理念:“我搭起一座始于实体作品、经由透视空间、通往精神世界的桥梁”。展览经历遍及欧美,曾于阿姆斯特丹市立博物馆(Stedelijk Museum),佛多尔美术馆 (Museum Fodor),苏黎世设计博物馆(Museum für Gestaltung)、第8届爱沙尼亚三年展Tallinn Applied Art Triennal等展出。作品集 ‘A Selection of Works’ 获评选为‘The Best Dutch Book Designs 2019’。作品获阿姆斯特丹市立美术馆(Stedelijk Musuem Amsterdam)、 荷兰AkzoNobel Art Foundation、荷兰银行(ABN AMRO)、德国私人美术馆(Sammlung Schroth)等永久收藏。

雷诺・奥德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn成长于荷兰乡村,最近的邻居相距1.5km以上,童年在偌大的田野与多雾的森林中遨游,热爱绘画的他,培养出对雾中变幻风景细微观察的兴趣。进入学院后开启不同艺术创作阶段:

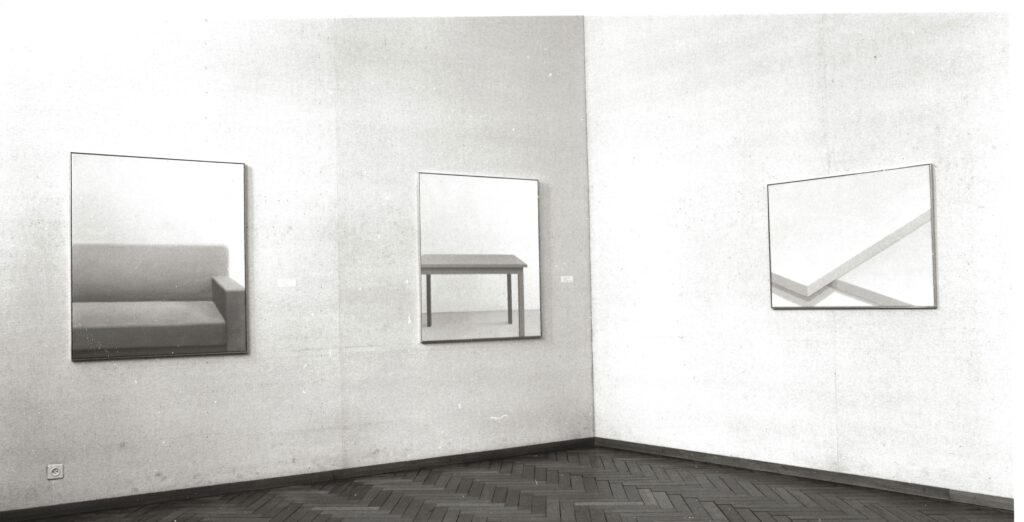

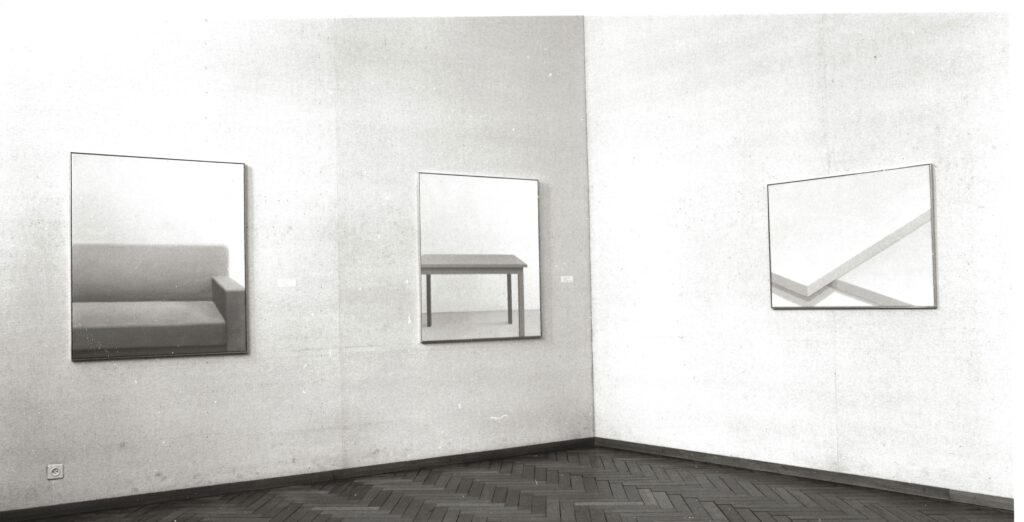

1. 绘画风格时期(distilled minimal fragments of interiors):学院时受到 ‘de Stijl’ 荷兰风格派主义运动,杰出的极简风格绘画人称“蒸馏极简空间片段”(distilled minimal fragments of interiors),受邀阿姆斯特丹美术馆(Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam )作品展出于蒙德里安Mondrian 、马勒维奇Malevich之间。

作品于阿姆斯特丹美术馆(Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam )展出

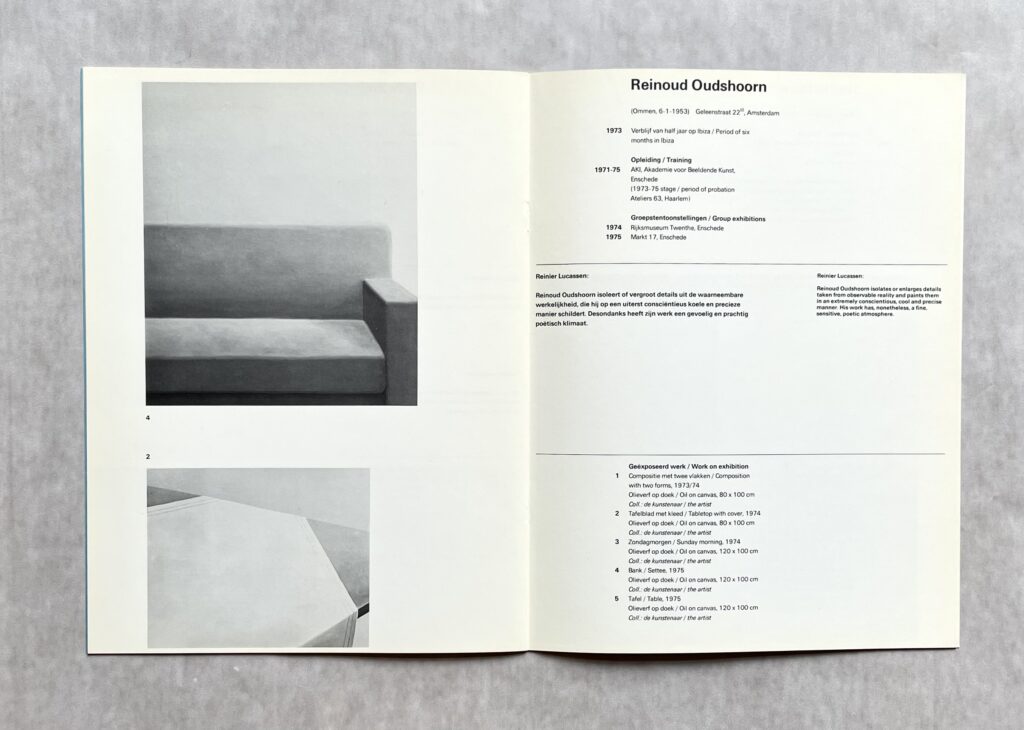

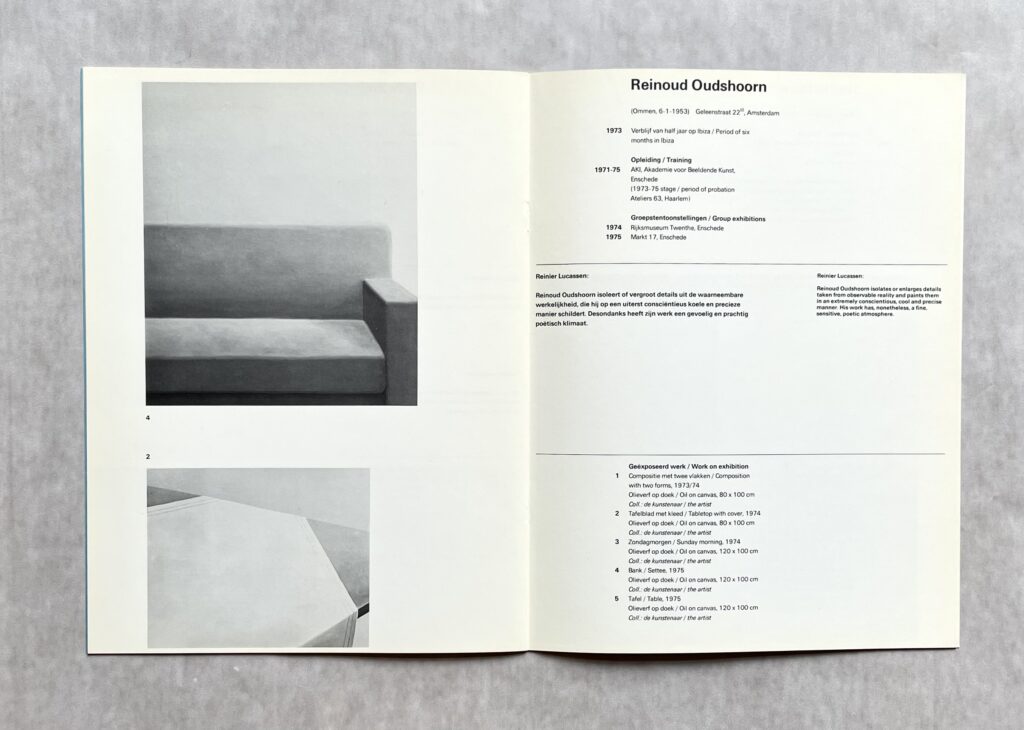

Oudshoorn’s page in the catalogue, the paintings are from 1973 – 1975

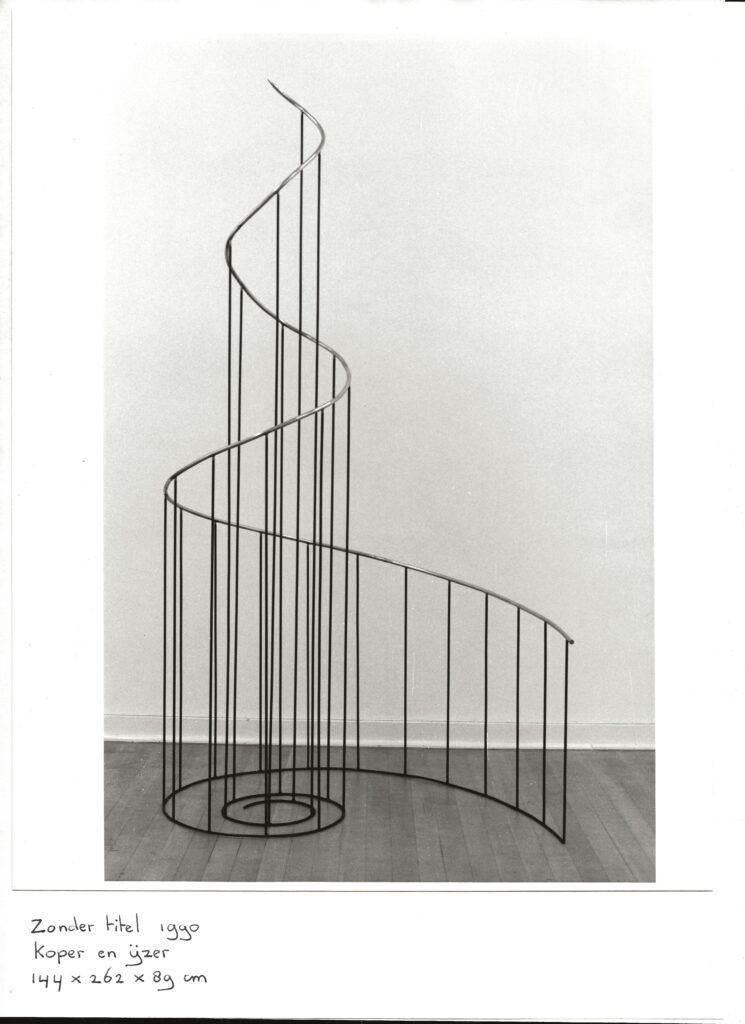

2.透视法雕塑转换时期:自80年代起绘画日益抽象简化,不满足于二维绘画的表现型式,逐渐展开对三维空间立体创作的实验。向往Paolo Uccello(1397-1475) 着迷于透视法中蕴藏着无限的魅力,以及Ellsworth Kelly、Barnet Newman 对于空间精准度、清晰度的影响,开始研究实验透视法雕塑,大量使用木头、铅、铁、铜、青铜、纸..等材质,以手工打造创作抽象极简雕塑。同时执教荷兰皇家艺术学院长达33年。

an early work from 1990, A-90, lead on wood 180 x 84 x 84 cm

an early work from 1990, copper and steel 144 x 262 x 89 cm.

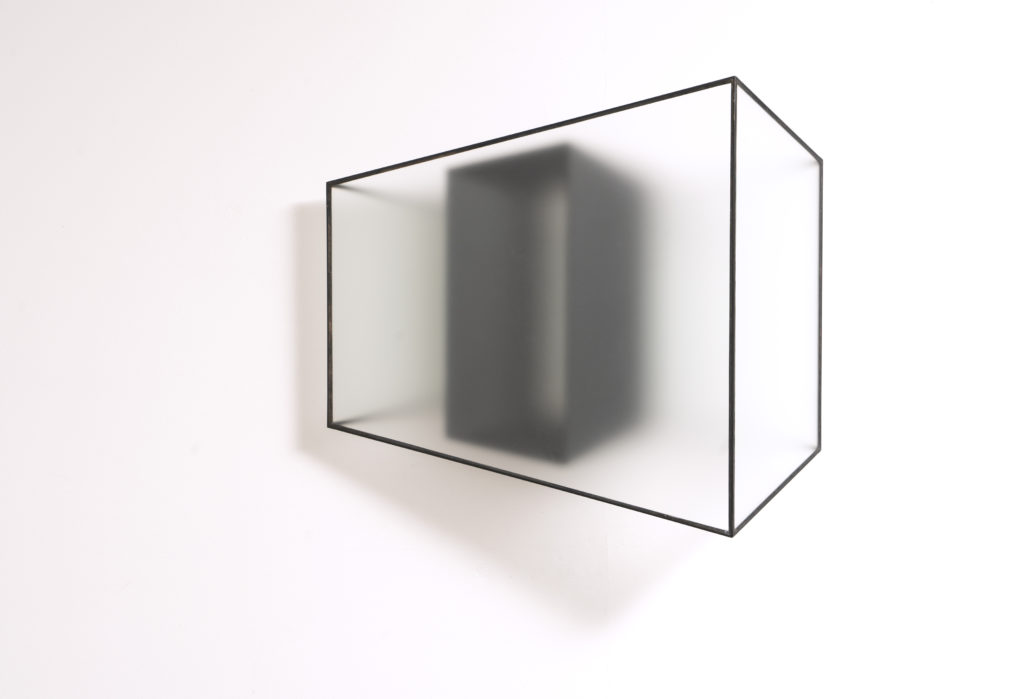

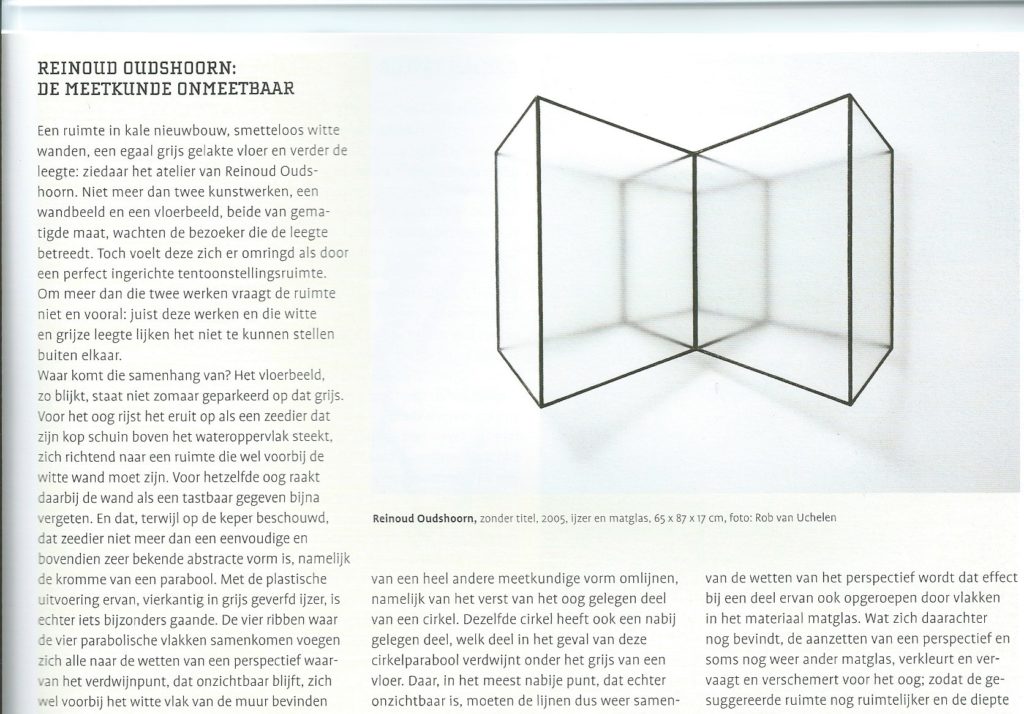

3.灭点雕塑时期:自90年代起至今,深入研究 “视觉的模拟两可性” (ambiguity of seeing),专注透视法与空间的探索,将灭点(Vanishing Point)的视觉高度统一设在1.65M,复杂的创作过程中,以手绘草稿、数学运算、手做模型,掌握透视、精密度、不同材质精准镶接,游刃于作品、想象、诗意空间三阶段进化的创作风格。此时期材质简化为黑铁、钢材、毛玻璃、木质等,以黑色透明的单色,重现幼时多雾森林的多维度框景。受犹太历史博物馆(Jewish Historisch Museum)、委托创作,与阿姆斯特丹基金会合作,为900户每户新住宅创作独有数字门牌雕塑。

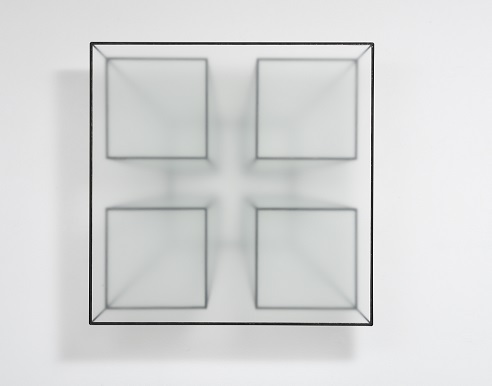

Reinoud Oudshoorn| G-21|64x64x22cm| Steel and frosted glass

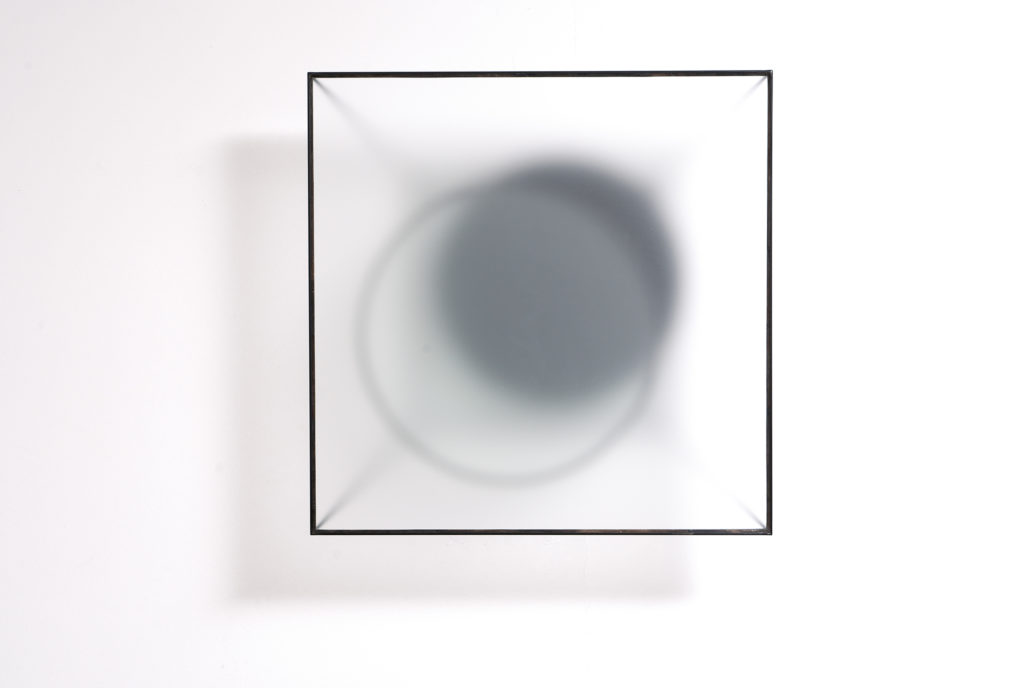

Q-20| 64x70x24cm|Steel and frosted glass

自古罗马时期艺术家就对透视有一定的认识,两条并行线在某个点聚集后消失,就是灭点。公元1011年阿拉伯科学家海什木Ibn al-Haytham的《光学全书》Perspectiva翻译拉丁文就是 “光的科学” 透视(Perspective),文艺复兴意大利画家马萨乔Masaccio(1401~1428)是第一位在绘画中使用线性透视,也是第一位在艺术中使用灭点技巧,自此艺术家营造平面绘画时,为使其具象化的透视手法,任何⻆度观看都只有一个灭点,将观者的视线牵引到艺术家想要带到的位置上,从而达到视觉上的收束。20世纪荷兰风格派运动(De Stijl)主张抽象和简化,外形上缩减到几何形状,颜色只用红、黄、蓝三原色与黑、白二非色彩的原色。艺术家们共同关心的问题是简化至本质的艺术元素,平面、直线、矩形成为艺术中的支柱,并通过数学的计算来达到视觉平衡 。奥德霍恩Oudshoorn的作品则开创多维风景,他进一步将此概念延伸在白墙、地板,创作被定义为一种载体,观者在接近墙面的那一刻,便可以体验一种图像,而这样的图像让空间感变得与众不同,观者视觉被牵引至想象灭点,进而打开大脑感官思维,进入想象世界遨翔。

这次于Bluerider ART上海·外滩”1.65”-雷诺・奥德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn 中国大陆首个展,将展出其代表作、最新作品及手稿。展名“1.65”代表1.65M不仅是视觉灭点、消失点,也是打开大脑诗意空间的进入点。整个展埸由一条1.65M高的隐形水平线,串连起每一件展出作品,这些统一1.65M灭点高度的雕塑,每一件又各自拥有墙内延伸空间、墙外拓展空间、脑海中的诗意空间。作品K-10以多件极细黑铁线条组合,有如鸟羽翅膀凌空飞舞,层层迭迭延伸入⽩墙,宛如一幅空间中的立体绘画。作品C-21 由12片薄黑铁片组成,极简的外型呈现线与⾯的多重延伸、多个灭点,诱发观众在移动中,仔细发掘多层次空间的奥妙。展出的艺术家设计手稿,密密麻麻数学计算公式,有如速描作品,呈现艺术家创作思维历程。

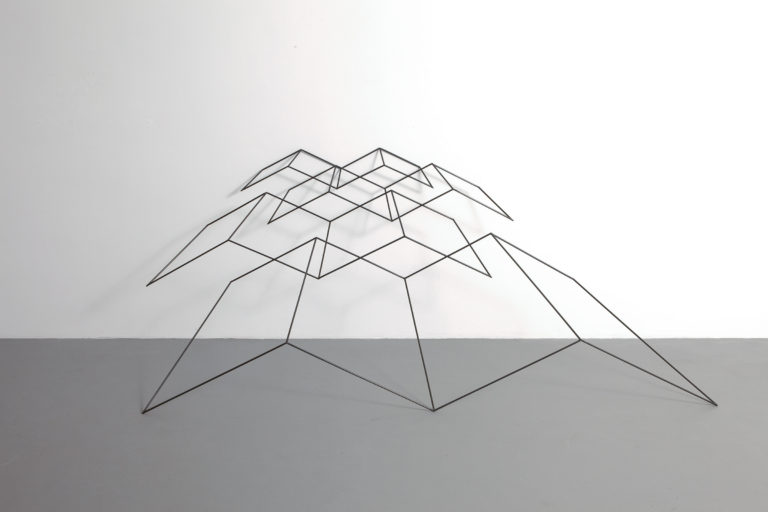

Reinoud Oudshoorn|K-10 | 2010 | 112 x 277 x 109cm | Iron

Reinoud Oudshoorn|C-21|2021|115x150x24cm|Iron

雷诺・奥德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn 作品削弱了现代雕塑的特质- 量体、材质、现实,他的计算成了再现与幻觉,在雕塑及非雕塑之间走出一条独特的路,数十年精钻精神埋首一贯理念:“我搭起一座始于实体作品、经由透视空间、通往精神世界的桥梁”。雕塑不仅呈现自身的量体,也并非只是空间减法,而是创造延伸的诗意空间,看似黑铁的冷静精准,实则带东方哲学禅意,细腻虚实穿透,优雅的、梦幻的灭点, 带给观者许多生命美好定格的宁静时刻。

‘1.65’

— 雷诺·奥德霍恩Reinoud Oudshoorn中国首个展

◼️媒体预览 Press Preview:

10.29 Sat. 2pm – 4pm

◼️VIP Opening开幕式(藏家预览):

10.29 Sat. 2pm – 5pm

◼️Open to public大众开放:

10.29 Sat. 5pm – 7pm

◼️展期:

2022.10.29-12.25

◼️地点:

Bluerider ART 上海·外滩

周二~周日 10am-7pm

上海黄浦区四川中路 133 号

作品 Works

艺术家 Artist

Reinoud Oudshoorn 雷诺·奥德霍恩

(Netherland, b. 1953)

雷诺・奥德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn(荷兰,b.1953) 荷兰阿特利尔63学院艺术硕士(MFA, The Ateliers 63 Haarlem),阿尔特兹艺术学士(BFA, AKI School of Arts, Enschede),现居住创作于荷兰阿姆斯特丹,曾执教于荷兰皇家艺术学院。雷诺・奥德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn以构筑空间的极简雕塑著称,认为解决问题是一切创作根源。统一设在1.65M高的灭点(Vanishing Point),从此开启每件作品的生命里程,透过单色极简材质的细腻叙述,点线面多点交错灭点的独特语言风格,实现其一贯理念:“我搭起一座始于实体作品、经由透视空间、通往精神世界的桥梁”。展览经历遍及欧美,曾于阿姆斯特丹市立博物馆(Stedelijk Museum),佛多尔美术馆 (Museum Fodor),苏黎世设计博物馆(Museum für Gestaltung)、第8届爱沙尼亚三年展Tallinn Applied Art Triennal等展出。作品集 ‘A Selection of Works’ 获评选为‘The Best Dutch Book Designs 2019’。作品获阿姆斯特丹市立美术馆(Stedelijk Musuem Amsterdam)、 荷兰AkzoNobel Art Foundation、荷兰银行(ABN AMRO)、德国私人美术馆(Sammlung Schroth)等永久收藏。

2021年于爱沙尼亚Kai Art Center第8届Tallinn Applied Art Triennal三年展”Translucency”参展

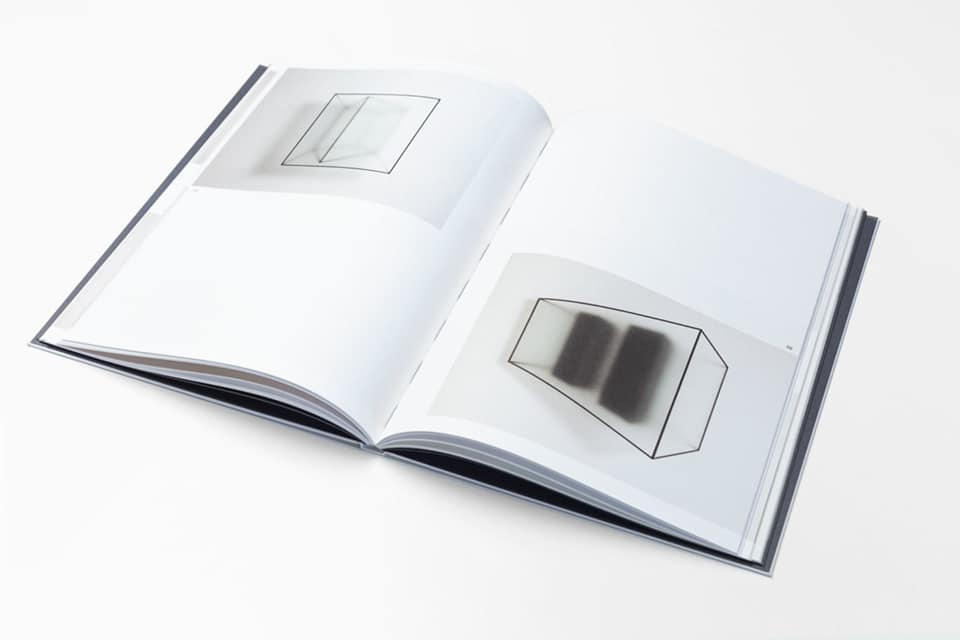

作品集“作品选集”自278位设计书籍竞逐中,获得专业化为“2019年荷兰最佳图书设计”。33位获奖书于荷兰最重要的当代美术馆Stedelijk博物馆阿姆斯特丹市立博物馆拍卖。

雷诺・奥德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn成长于荷兰乡村,最近的邻居相距1.5km以上,童年在偌大的田野与多雾的森林中遨游,热爱绘画的他,培养出对雾中变幻风景细微观察的兴趣。进入学院后开启不同艺术创作阶段:

1. 绘画风格时期(distilled minimal fragments of interiors):学院时受到 ‘de Stijl’ 荷兰风格派主义运动,杰出的极简风格绘画人称“蒸馏极简空间片段”(distilled minimal fragments of interiors),受邀阿姆斯特丹美术馆(Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam )作品展出于蒙德里安Mondrian 、马勒维奇Malevich之间。

作品于阿姆斯特丹美术馆(Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam )展出

Oudshoorn’s page in the catalogue, the paintings are from 1973 – 1975

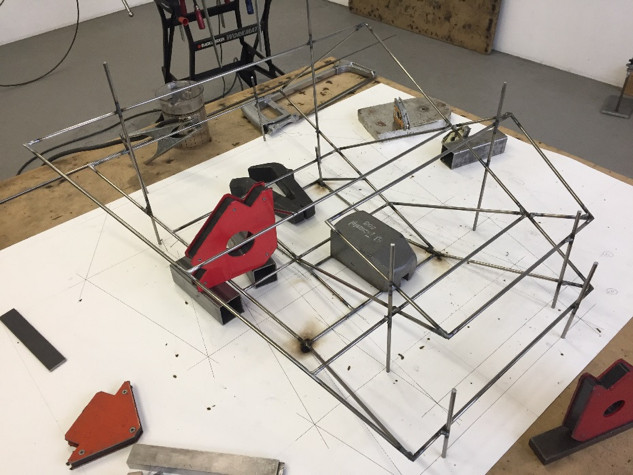

2.透视法雕塑转换时期:自80年代起绘画日益抽象简化,不满足于二维绘画的表现型式,逐渐展开对三维空间立体创作的实验。向往Paolo Uccello(1397-1475) 着迷于透视法中蕴藏着无限的魅力,以及Ellsworth Kelly、Barnet Newman 对于空间精准度、清晰度的影响,开始研究实验透视法雕塑,大量使用木头、铅、铁、铜、青铜、纸..等材质,以手工打造创作抽象极简雕塑。同时执教荷兰皇家艺术学院长达33年。

an early work from 1990, A-90, lead on wood 180 x 84 x 84 cm

an early work from 1990, copper and steel 144 x 262 x 89 cm.

3.灭点雕塑时期:自90年代起至今,深入研究 “视觉的模拟两可性” (ambiguity of seeing),专注透视法与空间的探索,将灭点(Vanishing Point)的视觉高度统一设在1.65M,复杂的创作过程中,以手绘草稿、数学运算、手做模型,掌握透视、精密度、不同材质精准镶接,游刃于作品、想象、诗意空间三阶段进化的创作风格。此时期材质简化为黑铁、钢材、毛玻璃、木质等,以黑色透明的单色,重现幼时多雾森林的多维度框景。受犹太历史博物馆(Jewish Historisch Museum)、委托创作,与阿姆斯特丹基金会合作,为900户每户新住宅创作独有数字门牌雕塑。

Reinoud Oudshoorn| G-21|64x64x22cm| Steel and frosted glass

Q-20| 64x70x24cm|Steel and frosted glass

自古罗马时期艺术家就对透视有一定的认识,两条并行线在某个点聚集后消失,就是灭点。公元1011年阿拉伯科学家海什木Ibn al-Haytham的《光学全书》Perspectiva翻译拉丁文就是 “光的科学” 透视(Perspective),文艺复兴意大利画家马萨乔Masaccio(1401~1428)是第一位在绘画中使用线性透视,也是第一位在艺术中使用灭点技巧,自此艺术家营造平面绘画时,为使其具象化的透视手法,任何⻆度观看都只有一个灭点,将观者的视线牵引到艺术家想要带到的位置上,从而达到视觉上的收束。 20世纪荷兰风格派运动(De Stijl)主张抽象和简化,外形上缩减到几何形状,颜色只用红、黄、蓝三原色与黑、白二非色彩的原色。艺术家们共同关心的问题是简化至本质的艺术元素,平面、直线、矩形成为艺术中的支柱,并通过数学的计算来达到视觉平衡 。奥德霍恩Oudshoorn的作品则开创多维风景,他进一步将此概念延伸在白墙、地板,创作被定义为一种载体,观者在接近墙面的那一刻,便可以体验一种图像,而这样的图像让空间感变得与众不同,观者视觉被牵引至想象灭点,进而打开大脑感官思维,进入想象世界遨翔。

雷诺・奥德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn 作品削弱了现代雕塑的特质- 量体、材质、现实,他的计算成了再现与幻觉,在雕塑及非雕塑之间走出一条独特的路,数十年精钻精神埋首一贯理念:“我搭起一座始于实体作品、经由透视空间、通往精神世界的桥梁”。雕塑不仅呈现自身的量体,也并非只是空间减法,而是创造延伸的诗意空间,看似黑铁的冷静精准,实则带东方哲学禅意,细腻虚实穿透,优雅的、梦幻的灭点, 带给观者许多生命美好定格的宁静时刻。

Reinoud Oudshoorn 創作手稿,以數學的方式計算線條與視角

收藏纪录 Collection

媒体报导 Press

Tekst Hans Sizoo

Tekst Hans Sizoo

Wide Walls

Wide Walls

Style Master

Style Master

Reinoud Oudshoorn

(Netherland, b. 1953)

Solo Exhibition

2020 Fragmented Truth (with Alice Quaresma), Patrick Heide Contemporary Art, London

2019 Vanishing Point,Bluerider ART, Taipei, Taiwan

2017 Dimensions of three, Allouche Gallery, New York, US

2017 Recent Sculptures, Patrick Heide Art Company, London, UK

2015 Ramakers Gallery, The Hague, The Netherlands

2013 Recent Sculptures, Patrick Heide Art Company, London, UK

2012 Dimensions, Gallery Skape, Seoul, South Korea

2011 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2010 Poetic reality in space, Gallery Skape, Seoul, South Korea

2009 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2008 Art Amsterdam, Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2008 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2005 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2003 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2000 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1998 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1996 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1995 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1994 Path Gallery, Aalst, Belgium

1993 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1992 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1991 Path Gallery, Aalst, Belgium

1990 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1988 Waalkens Gallery, Finsterwolde, The Netherlands

1987 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1985 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1983 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1981 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1979 Museum Fodor, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1978 Waalkens Gallery, Finsterwolde, The Netherlands

Group Exhibition

2022 The Blue Danube, Bluerider ART ,Shanghai , China

2021 Mental Space,Bluerider ART ,Taipei. , Taiwan

2020 For the Love of Art Part 1and 2, Gallery Ramakers, The Hague

2020 Gallery Ramakers at Art Rotterdam.

2019 Uit het atelier, Gallery Ramakers, The Hague, The Netherlands

2018 3D “Schrift am Bau”, Museum für Gestaltung, Zürich, Switzerland

2018 Volta NY, Allouche Gallery, New York, USA

2017 Machinerie, Proviciehuis, Haarlem, The Netherlands

2017 Art Rotterdam, Ramakers Gallery, The Netherlands

2017 Art Geneva, Patrick Heide, Geneva, Switzerland

2016 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide, Miami, USA

2016 Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day, Ramakers Gallery, The Hague, The

Netherlands

2016 Grand opening new space” Gallery Allouche Gallery, New York, USA

2016 Volta Basel, Patrick Heide, Basel, Switzerland

2016 Konstruction Construction, Museum Sammlung Schroth, Soest, Germany

2016 Art Geneva, Patrick Heide, Geneva, Switzerland

2016 Licht en transparantie, Thomas Elshuis en Reinoud Oudshoorn, Nieuw

Dakota, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2016 Ramakers Gallery, The Hague, The Netherlands

2015 Patrick Heide Gallery on the Miami Pulse, Miami, USA

2015 A call for drawing, Symposium, HKU, Utrecht, The Netherlands

2015 Volta Basel, Patrick Heide Gallery, Basel, Switzerland.

2014 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami, USA

2014 Nanjing International Art Festival, Nanjing, China.

2014 Short-hand-made, Grindel 117, Hamburg. Germany.

2014 20 years anniversary, Ramakers Gallery, The Hague, The Netherlands

2014 Volta Basel, Patrick Heide Gallery, Basel, Switzerland.

2013 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami, USA

2013 Hidden dimension, Gallery Skape, Seoul, South Korea.

2013 The last picture show, Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2013 Hidden dimension, Gallery Skape, Seoul, South Korea

2013 Capriccio, JCA de KOK centre for contemporary art, The Hauge, The

Netherlands

2013 Reinoud Oudshoorn and Jérôme Touron, Ramakers Gallery, The Hauge, The

Netherlands

2012 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami, USA

2012 Gallery Skape, Gallery Seoul Art Fair, Seoul, South Korea

2011 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami, USA

2011 Permanent Exibition, Skape Gallery, Seoul, South Korea

2010 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami USA

2010 Space A 2010, Gallery Space, Seoul, South Korea

2008 Ten Feet De Vishal, Haarlem, The Netherlands

2007 De keuze van Lucassen Ramakers Gallery, The Hague

2006 Façade Arti et Amicitiae, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2001 A Public Space 2001 Odyssey Arti et Amicitiae, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1997 Nooit zag ik Awater zo nabij Oude Kerkje, Kortenhoef, The Netherlands

1997 One Line Drawing, Ubu Gallery, New York, USA

1996 The Dutch Connection Marshall Art Gallery, Memphis TN, USA

1996 Weatherview Norwich Gallery, Norwich, UK

1994 The Collection Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1994 De keuze van Betty van Garrel Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The

Netherlands

1993 Atelier Mémoire, Paris, France

1993 20 Years Wetering Gallery Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1993 Kai,Sagaert et Oudshoorn Atelier Mémoire, Paris, France

1992 Le Génie de la Bastille Paris, France

1992 Gemeente Kunstaankopen 1991 Museum Fodor, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1990 Liberations Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1989 Kunstlijn Sculpture Route Zwolle-Emmen, The Netherlands

1989 AMRO Bank Collection, A Choice Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The

Netherlands

1988 Spiel der Uberraschungen der Europaïschen Kunst des 20 Jahrhundert,

Bochholt, Germany

1986 KunstRai, Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1984 De Kampanje, Den Helder, The Netherlands

1981 Felison op Beeckestijn, with Marlene Dumas, Velzen Zuid, The Netherlands

1979 Van Krimpen Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1976 11 Painters, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1975 Markt 17, Enschede, The Netherlands

1974 Rijksmuseum Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands

Collections

Akzo Nobel Art Foundation

Collection Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

ABN AMRO Art Collection

The Chadha Art Collection

Eleanore De Sole Collection

Joods historisch museum

University Medical Center Utrecht

Collection Sammlung Schroth, Germany