看展覽 Exhibition

預告片 Trailer

藝術家訪談影片

導覽影片

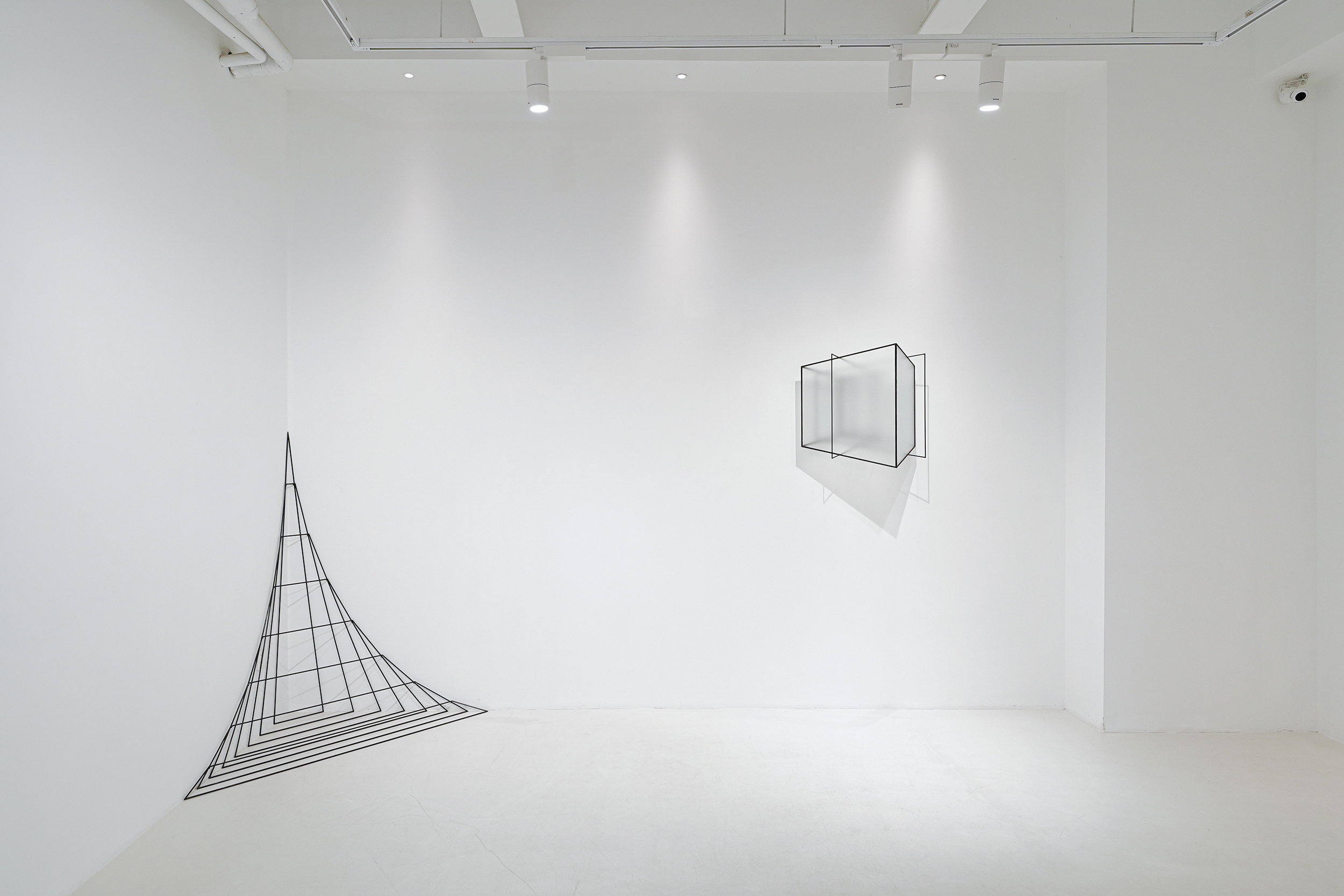

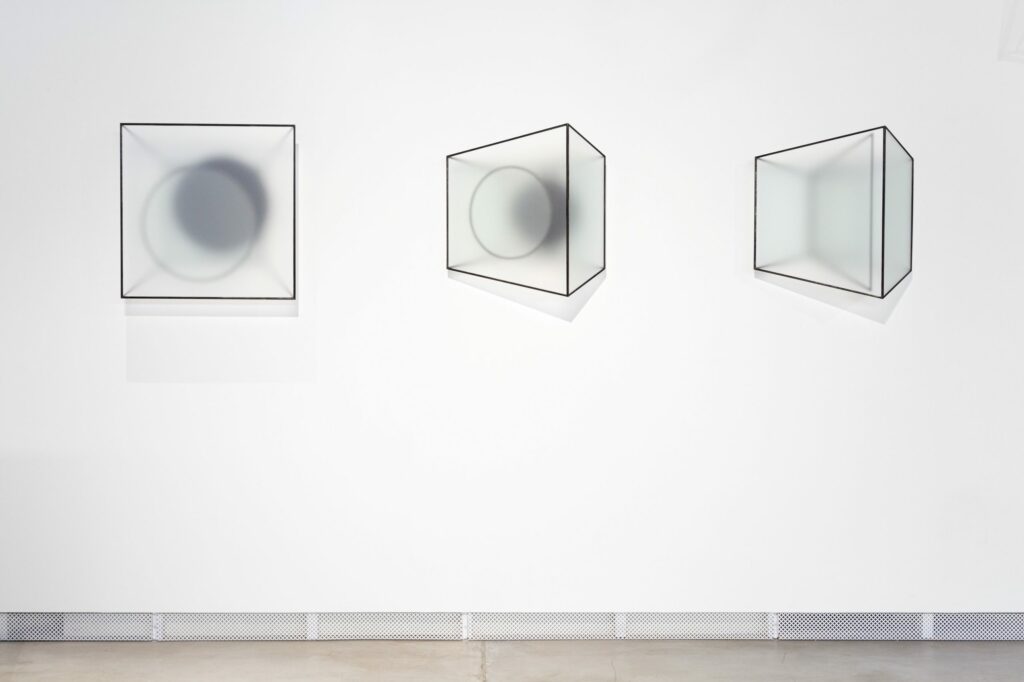

展場照片

看展Tips提示:

☝️尋找那條沿著展埸1.65米高,看不見的隱形水平線、和消失點

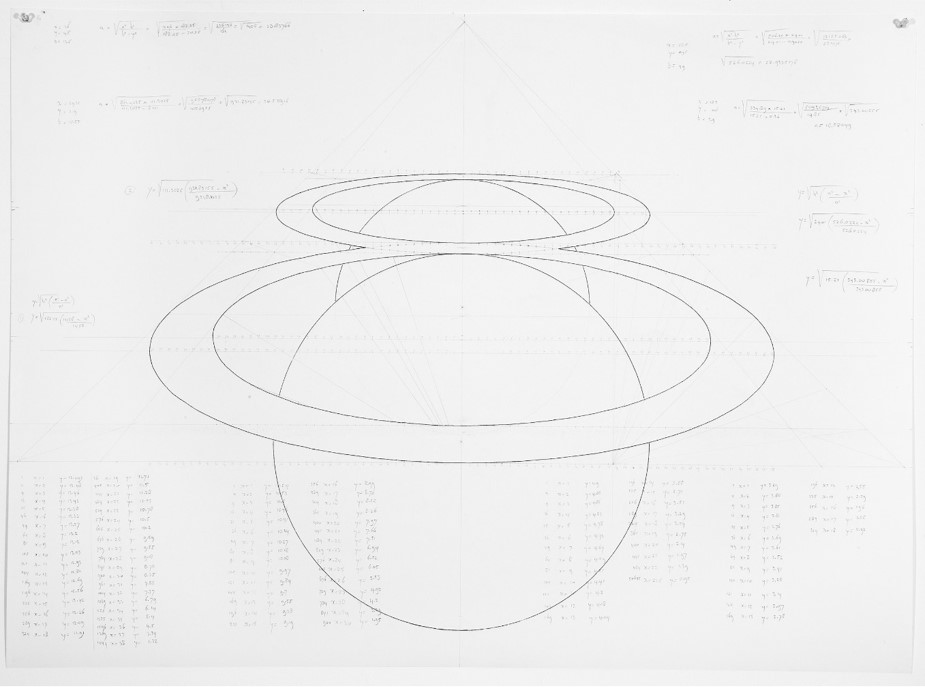

✌️別忘了欣賞那些密密麻麻、數學運算的過程手稿

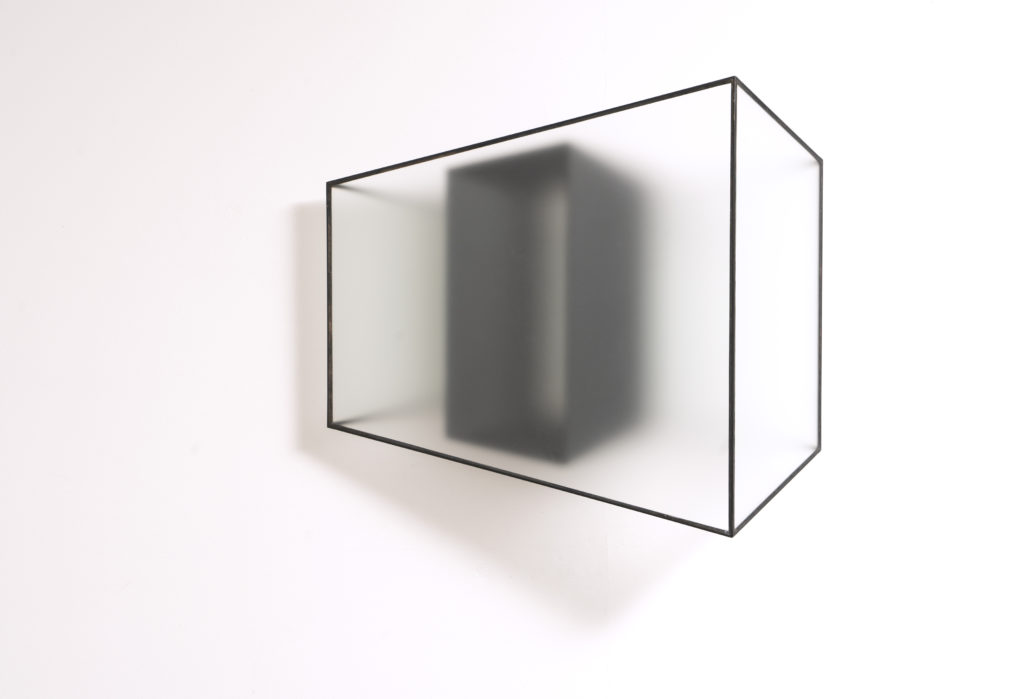

👌對著窗型作品緩緩地左右走動,發掘霧裡的風景忽隱忽現

p.s. 視覺高度不夠1.65米高,可以櫃臺借小矮櫈

開幕日現場影片

開幕日照片

‘1.65’ — 雷諾·奧德霍恩Reinoud Oudshoorn中國首個展

Bluerider ART 上海・外灘

2022.10.29-12.25

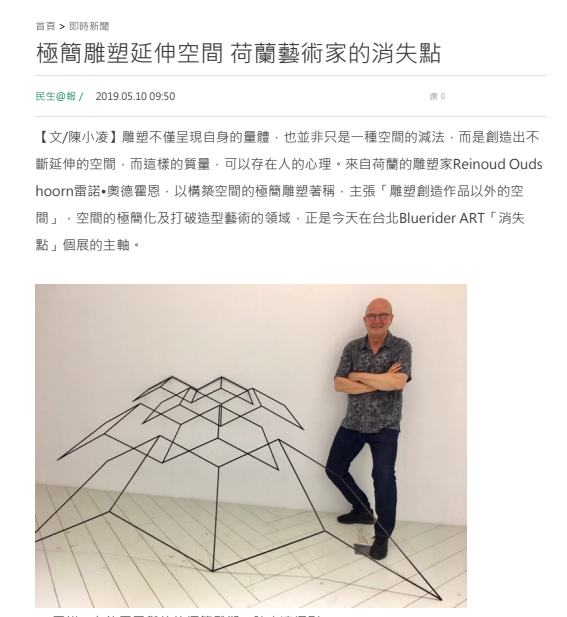

雷諾・奧德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn(荷蘭,b.1953) 荷蘭阿特利爾63學院藝術碩士(MFA, The Ateliers 63 Haarlem),阿爾特茲藝術學士(BFA, AKI School of Arts, Enschede),現居住創作於荷蘭阿姆斯特丹,曾執教於荷蘭皇家藝術學院。雷諾・奧德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn以構築空間的極簡雕塑著稱,認為解決問題是一切創作根源。統一設在1.65M高的滅點(Vanishing Point),從此開啟每件作品的生命裏程,透過單色極簡材質的細膩敘述,點線面多點交錯滅點的獨特語言風格,實現其一貫理念:“我搭起一座始於實體作品、經由透視空間、通往精神世界的橋梁”。展覽經歷遍及歐美,曾於阿姆斯特丹市立博物館(Stedelijk Museum),佛多爾美術館 (Museum Fodor),蘇黎世設計博物館(Museum für Gestaltung)、第8屆愛沙尼亞三年展Tallinn Applied Art Triennal等展出。作品集 ‘A Selection of Works’ 獲評選為‘The Best Dutch Book Designs 2019’。作品獲阿姆斯特丹市立美術館(Stedelijk Musuem Amsterdam)、 荷蘭AkzoNobel Art Foundation、荷蘭銀行(ABN AMRO)、德國私人美術館(Sammlung Schroth)等永久收藏。

雷諾・奧德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn成長於荷蘭鄉村,最近的鄰居相距1.5km以上,童年在偌大的田野與多霧的森林中遨遊,熱愛繪畫的他,培養出對霧中變幻風景細微觀察的興趣。進入學院後開啟不同藝術創作階段:

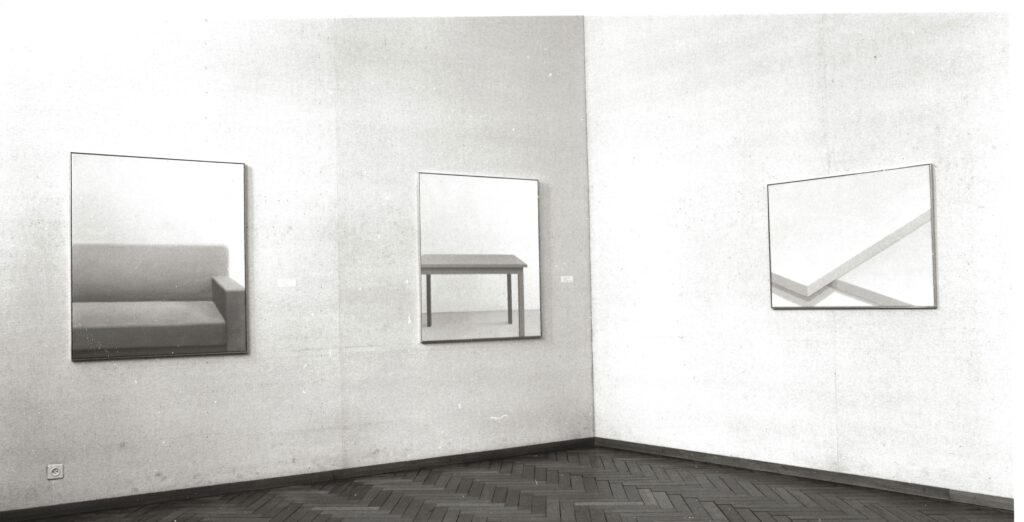

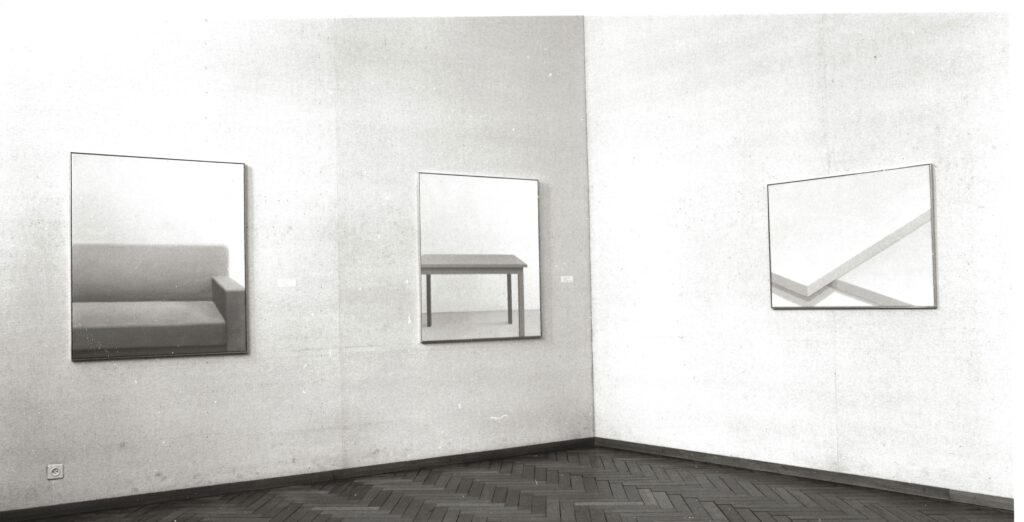

1.繪畫風格時期(distilled minimal fragments of interiors):學院時受到 ‘de Stijl’ 荷蘭風格派主義運動,傑出的極簡風格繪畫人稱“蒸餾極簡空間片段”(distilled minimal fragments of interiors),受邀阿姆斯特丹美術館(Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam )作品展出於蒙德裏安Mondrian 、馬勒維奇Malevich之間。

作品於阿姆斯特丹美術館(Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam )展出

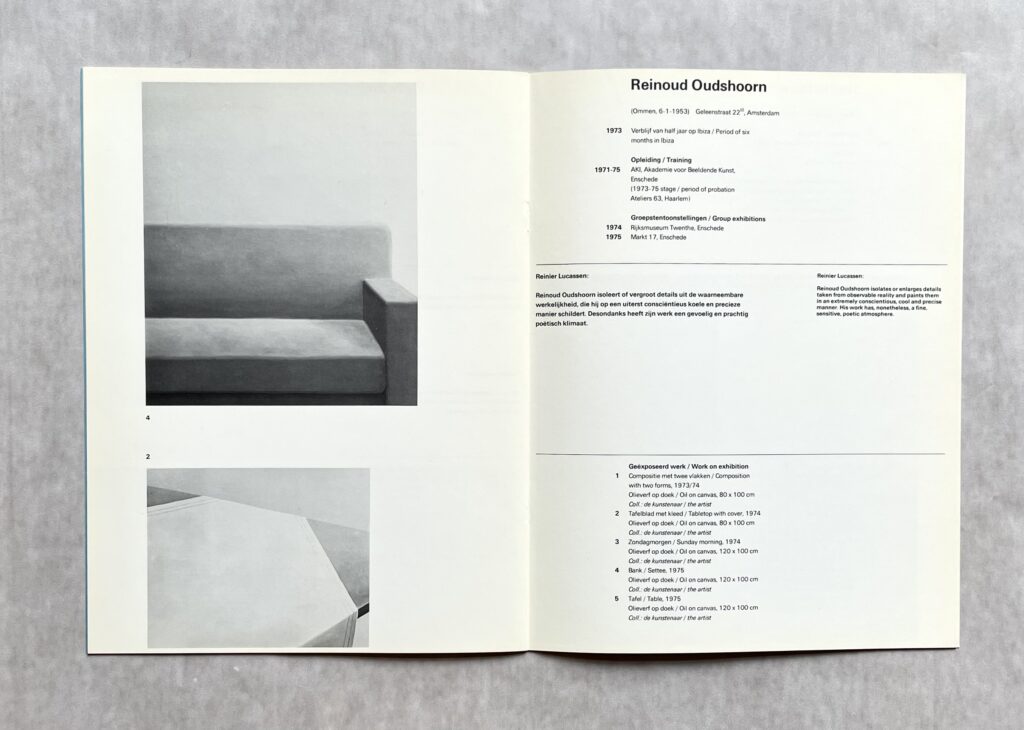

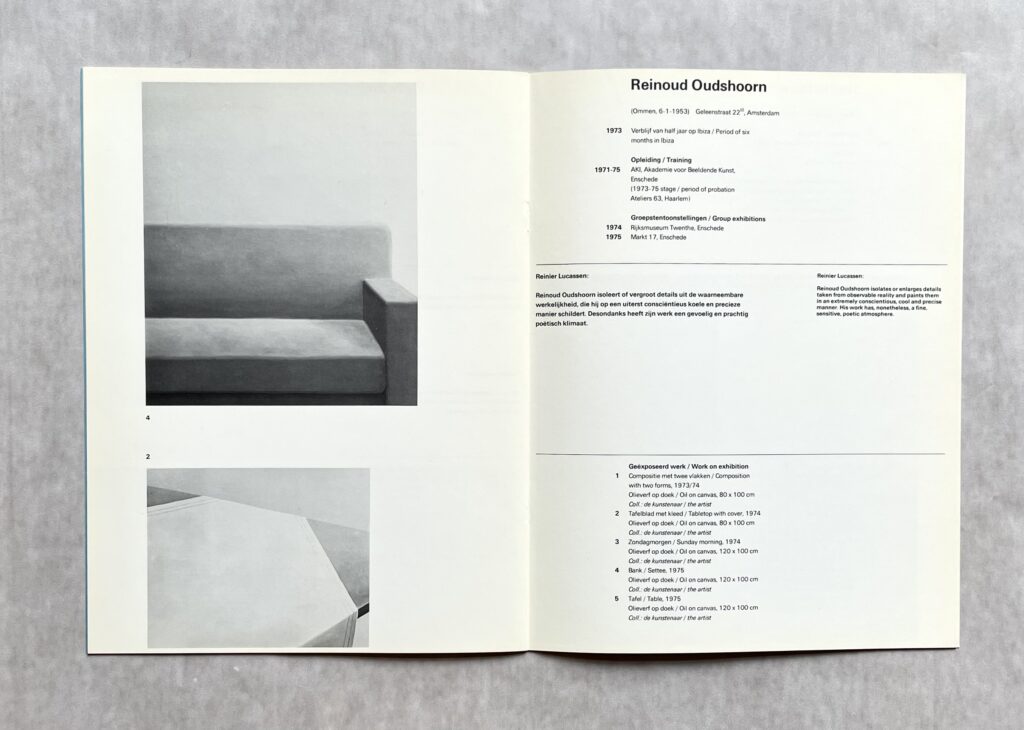

Oudshoorn’s page in the catalogue, the paintings are from 1973 – 1975

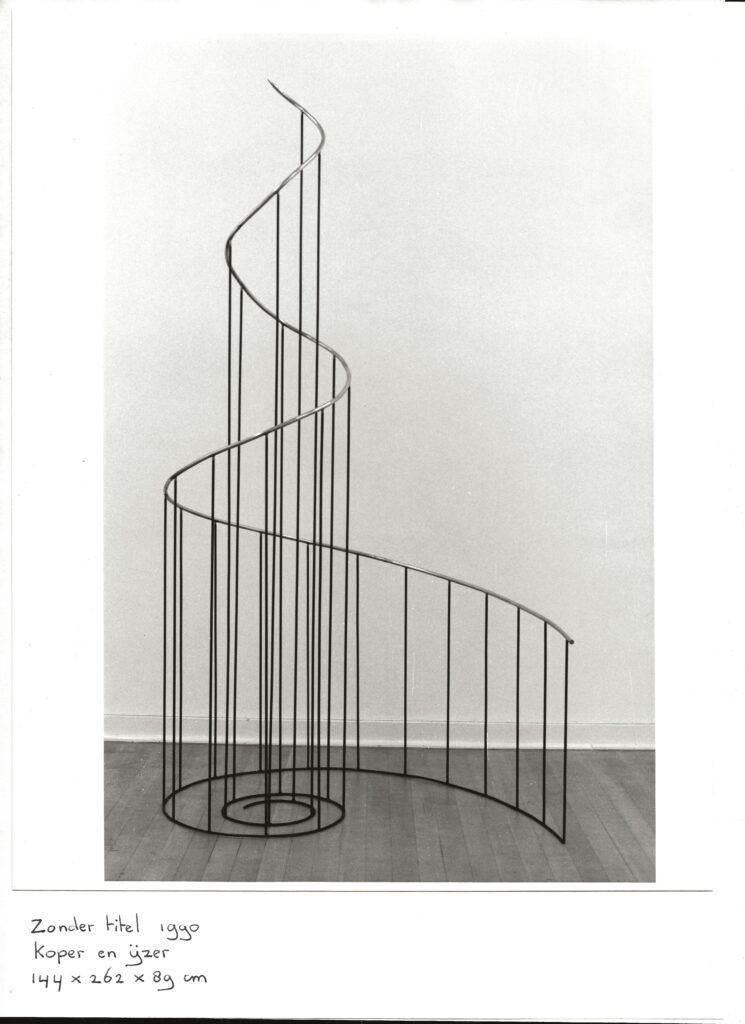

2.透視法雕塑轉換時期:自80年代起繪畫日益抽象簡化,不滿足於二維繪畫的表現型式,逐漸展開對三維空間立體創作的實驗。向往Paolo Uccello(1397-1475) 著迷於透視法中蘊藏著無限的魅力,以及Ellsworth Kelly、Barnet Newman 對於空間精準度、清晰度的影響,開始研究實驗透視法雕塑,大量使用木頭、鉛、鐵、銅、青銅、紙..等材質,以手工打造創作抽象極簡雕塑。同時執教荷蘭皇家藝術學院長達33年。

an early work from 1990, A-90, lead on wood 180 x 84 x 84 cm

an early work from 1990, copper and steel 144 x 262 x 89 cm.

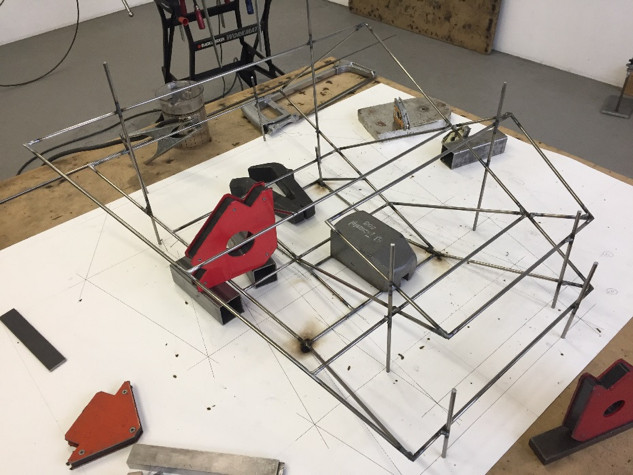

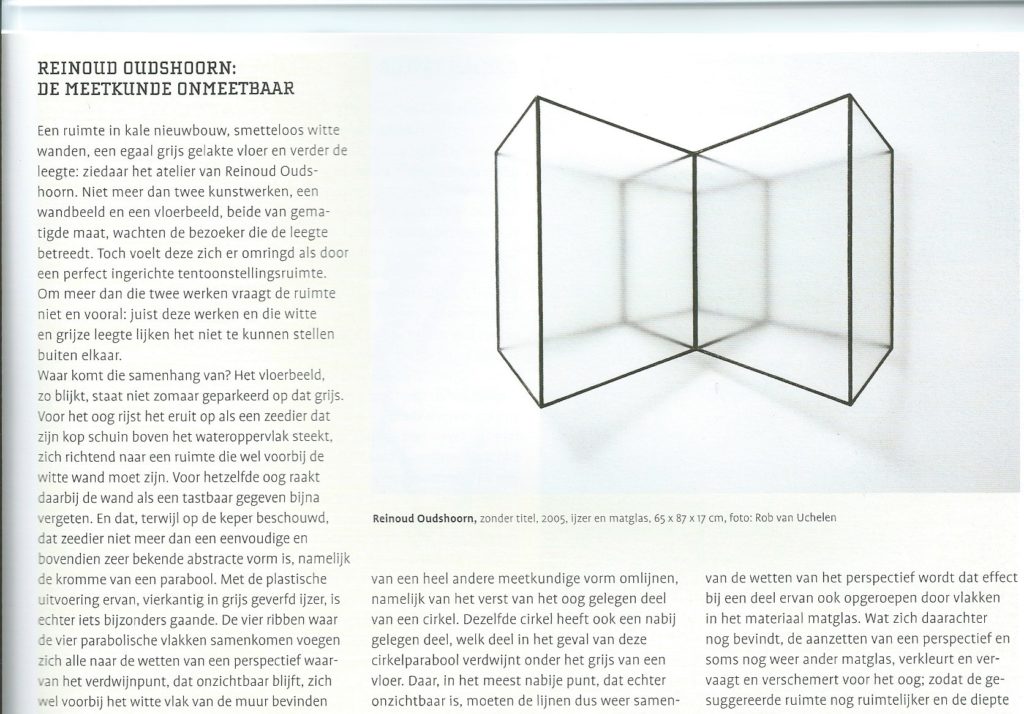

3.滅點雕塑時期:自90年代起至今,深入研究 “視覺的模擬兩可性” (ambiguity of seeing),專注透視法與空間的探索,將滅點(Vanishing Point)的視覺高度統一設在1.65M,復雜的創作過程中,以手繪草稿、數學運算、手做模型,掌握透視、精密度、不同材質精準鑲接,遊刃於作品、想象、詩意空間三階段進化的創作風格。此時期材質簡化為黑鐵、鋼材、毛玻璃、木質等,以黑色透明的單色,重現幼時多霧森林的多維度框景。受猶太歷史博物館(Jewish Historisch Museum)、委托創作,與阿姆斯特丹基金會合作,為900戶每戶新住宅創作獨有數字門牌雕塑。

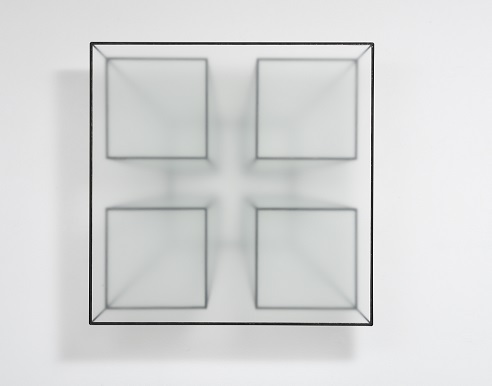

Reinoud Oudshoorn| G-21|64x64x22cm| Steel and frosted glass

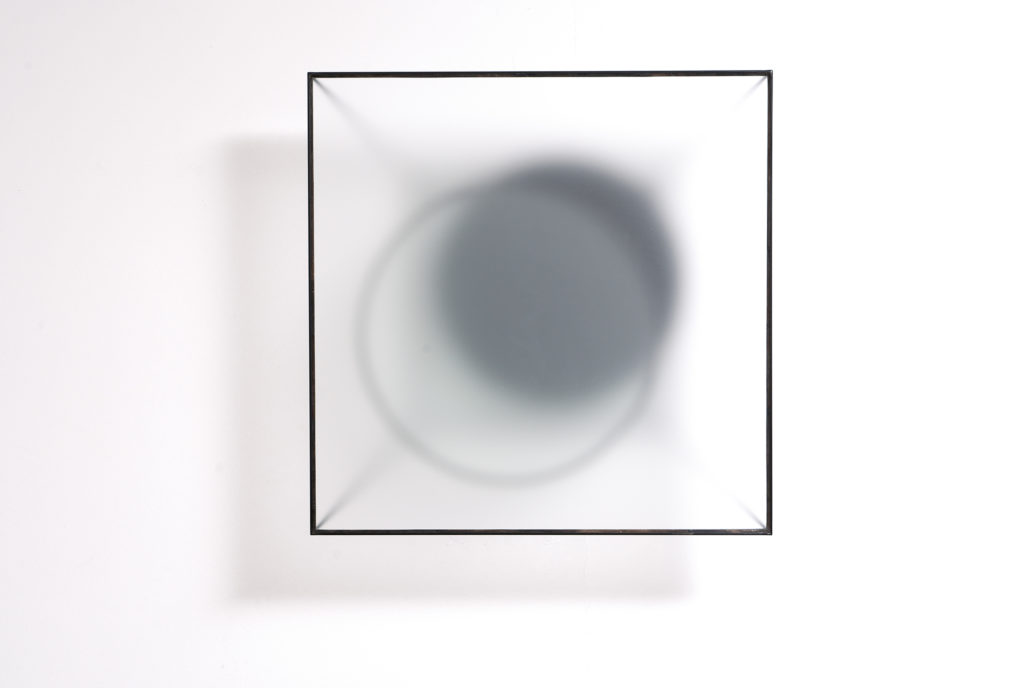

Q-20| 64x70x24cm|Steel and frosted glass

自古羅馬時期藝術家就對透視有一定的認識,兩條並行線在某個點聚集後消失,就是滅點。公元1011年阿拉伯科學家海什木Ibn al-Haytham的《光學全書》Perspectiva翻譯拉丁文就是 “光的科學” 透視(Perspective),文藝復興意大利畫家馬薩喬Masaccio(1401~1428)是第一位在繪畫中使用線性透視,也是第一位在藝術中使用滅點技巧,自此藝術家營造平面繪畫時,為使其具象化的透視手法,任何⻆度觀看都只有一個滅點,將觀者的視線牽引到藝術家想要帶到的位置上,從而達到視覺上的收束。20世紀荷蘭風格派運動(De Stijl)主張抽象和簡化,外形上縮減到幾何形狀,顏色只用紅、黃、藍三原色與黑、白二非色彩的原色。藝術家們共同關心的問題是簡化至本質的藝術元素,平面、直線、矩形成為藝術中的支柱,並通過數學的計算來達到視覺平衡 。奧德霍恩Oudshoorn的作品則開創多維風景,他進壹步將此概念延伸在白墻、地板,創作被定義為一種載體,觀者在接近墻面的那一刻,便可以體驗一種圖像,而這樣的圖像讓空間感變得與眾不同,觀者視覺被牽引至想象滅點,進而打開大腦感官思維,進入想象世界遨翔。

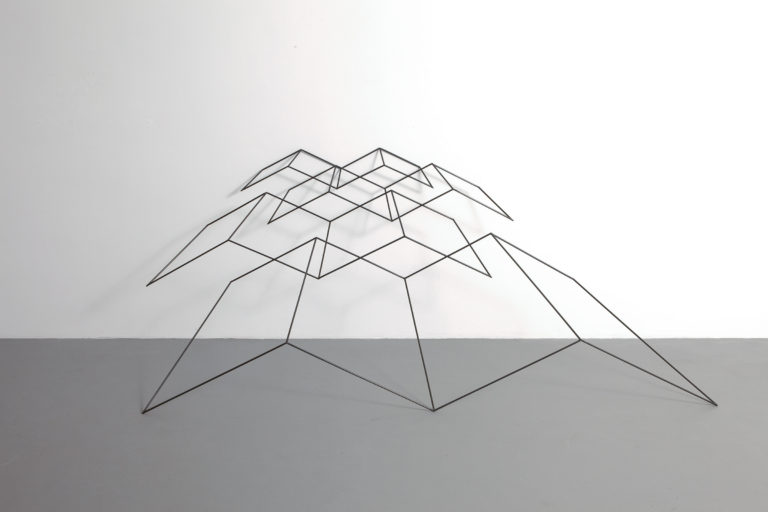

這次於Bluerider ART上海·外灘”1.65”-雷諾・奧德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn 中國大陸首個展,將展出其代表作、最新作品及手稿。展名“1.65”代表1.65M不僅是視覺滅點、消失點,也是打開大腦詩意空間的進入點。整個展埸由一條1.65M高的隱形水平線,串連起每一件展出作品,這些統一1.65M滅點高度的雕塑,每一件又各自擁有墻內延伸空間、墻外拓展空間、腦海中的詩意空間。作品K-10以多件極細黑鐵線條組合,有如鳥羽翅膀淩空飛舞,層層叠叠延伸入⽩墻,宛如一幅空間中的立體繪畫。作品C-21 由12片薄黑鐵片組成,極簡的外型呈現線與⾯的多重延伸、多個滅點,誘發觀眾在移動中,仔細發掘多層次空間的奧妙。展出的藝術家設計手稿,密密麻麻數學計算公式,有如速描作品,呈現藝術家創作思維歷程。

Reinoud Oudshoorn|K-10 | 2010 | 112 x 277 x 109cm | Iron

Reinoud Oudshoorn|C-21|2021|115x150x24cm|Iron

雷諾・奧德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn 作品削弱了現代雕塑的特質- 量體、材質、現實,他的計算成了再現與幻覺,在雕塑及非雕塑之間走出一條獨特的路,數十年精鉆精神埋首一貫理念:“我搭起一座始於實體作品、經由透視空間、通往精神世界的橋梁”。雕塑不僅呈現自身的量體,也並非只是空間減法,而是創造延伸的詩意空間,看似黑鐵的冷靜精準,實則帶東方哲學禪意,細膩虛實穿透,優雅的、夢幻的滅點, 帶給觀者許多生命美好定格的寧靜時刻。

‘1.65’

— 雷諾·奧德霍恩Reinoud Oudshoorn中國首個展

◼️媒體預覽 Press Preview:

10.29 Sat. 2pm – 4pm

◼️VIP Opening開幕式(藏家預覽):

10.29 Sat. 2pm – 5pm

◼️Open to public大眾開放:

10.29 Sat. 5pm – 7pm

◼️展期:

2022.10.29-12.25

◼️地點:

Bluerider ART 上海·外灘

周二~周日 10am-7pm

上海黃浦區四川中路 133 號

作品 Works

藝術家 Artist

Reinoud Oudshoorn 雷諾·奧德霍恩

(Netherland, b. 1953)

雷諾・奧德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn(荷蘭,b.1953) 荷蘭阿特利爾63學院藝術碩士(MFA, The Ateliers 63 Haarlem),阿爾特茲藝術學士(BFA, AKI School of Arts, Enschede),現居住創作於荷蘭阿姆斯特丹,曾執教於荷蘭皇家藝術學院。雷諾・奧德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn以構築空間的極簡雕塑著稱,認為解決問題是一切創作根源。統一設在1.65M高的滅點(Vanishing Point),從此開啟每件作品的生命裏程,透過單色極簡材質的細膩敘述,點線面多點交錯滅點的獨特語言風格,實現其一貫理念:“我搭起一座始於實體作品、經由透視空間、通往精神世界的橋梁”。展覽經歷遍及歐美,曾於阿姆斯特丹市立博物館(Stedelijk Museum),佛多爾美術館 (Museum Fodor),蘇黎世設計博物館(Museum für Gestaltung)、第8屆愛沙尼亞三年展Tallinn Applied Art Triennal等展出。作品集 ‘A Selection of Works’ 獲評選為‘The Best Dutch Book Designs 2019’。作品獲阿姆斯特丹市立美術館(Stedelijk Musuem Amsterdam)、 荷蘭AkzoNobel Art Foundation、荷蘭銀行(ABN AMRO)、德國私人美術館(Sammlung Schroth)等永久收藏。

2021年於愛沙尼亞Kai Art Center第8屆Tallinn Applied Art Triennal三年展”Translucency”參展

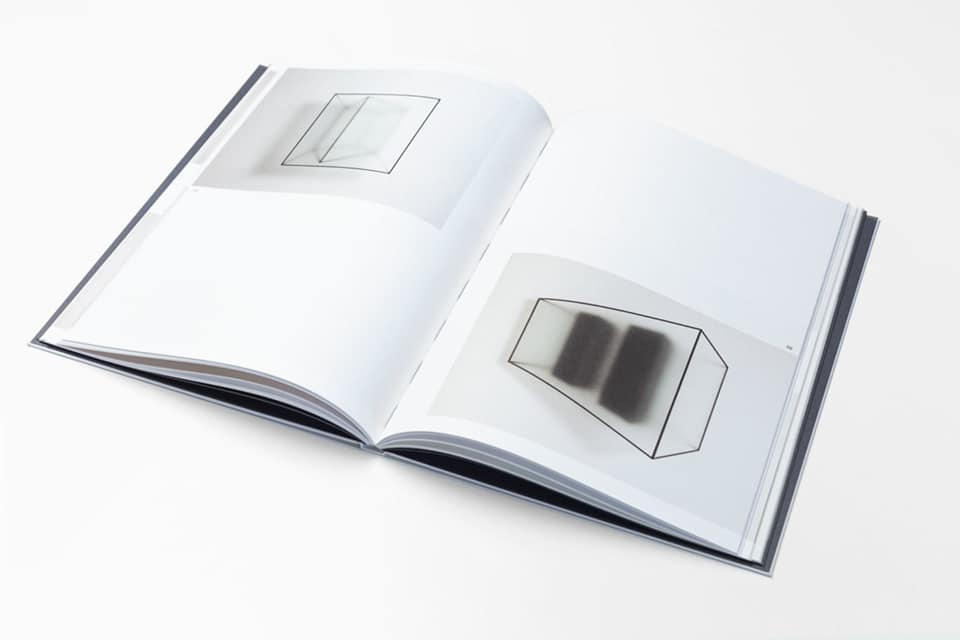

作品集 ‘A Selection of Works’ 自278位設計書籍競逐中,獲專業評選為‘The Best Dutch Book Designs 2019’。33位獲獎書於荷蘭最重要當代美術館 Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam阿姆斯特丹市立博物館展出。

雷諾・奧德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn成長於荷蘭鄉村,最近的鄰居相距1.5km以上,童年在偌大的田野與多霧的森林中遨遊,熱愛繪畫的他,培養出對霧中變幻風景細微觀察的興趣。進入學院後開啟不同藝術創作階段:

1.繪畫風格時期(distilled minimal fragments of interiors):學院時受到 ‘de Stijl’ 荷蘭風格派主義運動,傑出的極簡風格繪畫人稱“蒸餾極簡空間片段”(distilled minimal fragments of interiors),受邀阿姆斯特丹美術館(Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam )作品展出於蒙德裏安Mondrian 、馬勒維奇Malevich之間。

作品於阿姆斯特丹美術館(Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam )展出

Oudshoorn’s page in the catalogue, the paintings are from 1973 – 1975

2.透視法雕塑轉換時期:自80年代起繪畫日益抽象簡化,不滿足於二維繪畫的表現型式,逐漸展開對三維空間立體創作的實驗。向往Paolo Uccello(1397-1475) 著迷於透視法中蘊藏著無限的魅力,以及Ellsworth Kelly、Barnet Newman 對於空間精準度、清晰度的影響,開始研究實驗透視法雕塑,大量使用木頭、鉛、鐵、銅、青銅、紙..等材質,以手工打造創作抽象極簡雕塑。同時執教荷蘭皇家藝術學院長達33年。

an early work from 1990, A-90, lead on wood 180 x 84 x 84 cm

an early work from 1990, copper and steel 144 x 262 x 89 cm.

3.滅點雕塑時期:自90年代起至今,深入研究 “視覺的模擬兩可性” (ambiguity of seeing),專注透視法與空間的探索,將滅點(Vanishing Point)的視覺高度統一設在1.65M,復雜的創作過程中,以手繪草稿、數學運算、手做模型,掌握透視、精密度、不同材質精準鑲接,遊刃於作品、想象、詩意空間三階段進化的創作風格。此時期材質簡化為黑鐵、鋼材、毛玻璃、木質等,以黑色透明的單色,重現幼時多霧森林的多維度框景。受猶太歷史博物館(Jewish Historisch Museum)、委托創作,與阿姆斯特丹基金會合作,為900戶每戶新住宅創作獨有數字門牌雕塑。

Reinoud Oudshoorn| G-21|64x64x22cm| Steel and frosted glass

Q-20| 64x70x24cm|Steel and frosted glass

自古羅馬時期藝術家就對透視有一定的認識,兩條並行線在某個點聚集後消失,就是滅點。公元1011年阿拉伯科學家海什木Ibn al-Haytham的《光學全書》Perspectiva翻譯拉丁文就是 “光的科學” 透視(Perspective),文藝復興意大利畫家馬薩喬Masaccio(1401~1428)是第一位在繪畫中使用線性透視,也是第一位在藝術中使用滅點技巧,自此藝術家營造平面繪畫時,為使其具象化的透視手法,任何⻆度觀看都只有一個滅點,將觀者的視線牽引到藝術家想要帶到的位置上,從而達到視覺上的收束。20世紀荷蘭風格派運動(De Stijl)主張抽象和簡化,外形上縮減到幾何形狀,顏色只用紅、黃、藍三原色與黑、白二非色彩的原色。藝術家們共同關心的問題是簡化至本質的藝術元素,平面、直線、矩形成為藝術中的支柱,並通過數學的計算來達到視覺平衡 。奧德霍恩Oudshoorn的作品則開創多維風景,他進一步將此概念延伸在白墻、地板,創作被定義為一種載體,觀者在接近墻面的那一刻,便可以體驗一種圖像,而這樣的圖像讓空間感變得與眾不同,觀者視覺被牽引至想象滅點,進而打開大腦感官思維,進入想象世界遨翔。

雷諾・奧德霍恩 Reinoud Oudshoorn 作品削弱了現代雕塑的特質- 量體、材質、現實,他的計算成了再現與幻覺,在雕塑及非雕塑之間走出一條獨特的路,數十年精鉆精神埋首一貫理念:“我搭起一座始於實體作品、經由透視空間、通往精神世界的橋梁”。雕塑不僅呈現自身的量體,也並非只是空間減法,而是創造延伸的詩意空間,看似黑鐵的冷靜精準,實則帶東方哲學禪意,細膩虛實穿透,優雅的、夢幻的滅點, 帶給觀者許多生命美好定格的寧靜時刻。

Reinoud Oudshoorn 創作手稿,以數學的方式計算線條與視角

收藏紀錄 Collection

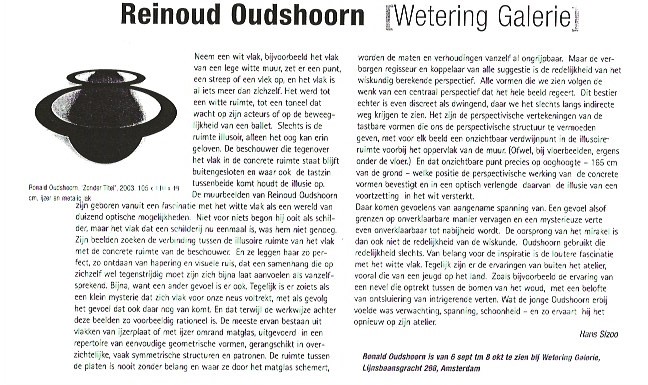

媒體報導 Press

Tekst Hans Sizoo

Tekst Hans Sizoo

Wide Walls

Wide Walls

Style Master

Style Master

Reinoud Oudshoorn

(Netherland, b. 1953)

Solo Exhibition

2020 Fragmented Truth (with Alice Quaresma), Patrick Heide Contemporary Art, London

2019 Vanishing Point,Bluerider ART, Taipei, Taiwan

2017 Dimensions of three, Allouche Gallery, New York, US

2017 Recent Sculptures, Patrick Heide Art Company, London, UK

2015 Ramakers Gallery, The Hague, The Netherlands

2013 Recent Sculptures, Patrick Heide Art Company, London, UK

2012 Dimensions, Gallery Skape, Seoul, South Korea

2011 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2010 Poetic reality in space, Gallery Skape, Seoul, South Korea

2009 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2008 Art Amsterdam, Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2008 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2005 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2003 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2000 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1998 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1996 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1995 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1994 Path Gallery, Aalst, Belgium

1993 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1992 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1991 Path Gallery, Aalst, Belgium

1990 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1988 Waalkens Gallery, Finsterwolde, The Netherlands

1987 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1985 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1983 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1981 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1979 Museum Fodor, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1978 Waalkens Gallery, Finsterwolde, The Netherlands

Group Exhibition

2022 The Blue Danube, Bluerider ART ,Shanghai , China

2021 Mental Space,Bluerider ART ,Taipei. , Taiwan

2020 For the Love of Art Part 1and 2, Gallery Ramakers, The Hague

2020 Gallery Ramakers at Art Rotterdam.

2019 Uit het atelier, Gallery Ramakers, The Hague, The Netherlands

2018 3D “Schrift am Bau”, Museum für Gestaltung, Zürich, Switzerland

2018 Volta NY, Allouche Gallery, New York, USA

2017 Machinerie, Proviciehuis, Haarlem, The Netherlands

2017 Art Rotterdam, Ramakers Gallery, The Netherlands

2017 Art Geneva, Patrick Heide, Geneva, Switzerland

2016 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide, Miami, USA

2016 Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day, Ramakers Gallery, The Hague, The

Netherlands

2016 Grand opening new space” Gallery Allouche Gallery, New York, USA

2016 Volta Basel, Patrick Heide, Basel, Switzerland

2016 Konstruction Construction, Museum Sammlung Schroth, Soest, Germany

2016 Art Geneva, Patrick Heide, Geneva, Switzerland

2016 Licht en transparantie, Thomas Elshuis en Reinoud Oudshoorn, Nieuw

Dakota, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2016 Ramakers Gallery, The Hague, The Netherlands

2015 Patrick Heide Gallery on the Miami Pulse, Miami, USA

2015 A call for drawing, Symposium, HKU, Utrecht, The Netherlands

2015 Volta Basel, Patrick Heide Gallery, Basel, Switzerland.

2014 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami, USA

2014 Nanjing International Art Festival, Nanjing, China.

2014 Short-hand-made, Grindel 117, Hamburg. Germany.

2014 20 years anniversary, Ramakers Gallery, The Hague, The Netherlands

2014 Volta Basel, Patrick Heide Gallery, Basel, Switzerland.

2013 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami, USA

2013 Hidden dimension, Gallery Skape, Seoul, South Korea.

2013 The last picture show, Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2013 Hidden dimension, Gallery Skape, Seoul, South Korea

2013 Capriccio, JCA de KOK centre for contemporary art, The Hauge, The

Netherlands

2013 Reinoud Oudshoorn and Jérôme Touron, Ramakers Gallery, The Hauge, The

Netherlands

2012 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami, USA

2012 Gallery Skape, Gallery Seoul Art Fair, Seoul, South Korea

2011 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami, USA

2011 Permanent Exibition, Skape Gallery, Seoul, South Korea

2010 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami USA

2010 Space A 2010, Gallery Space, Seoul, South Korea

2008 Ten Feet De Vishal, Haarlem, The Netherlands

2007 De keuze van Lucassen Ramakers Gallery, The Hague

2006 Façade Arti et Amicitiae, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2001 A Public Space 2001 Odyssey Arti et Amicitiae, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1997 Nooit zag ik Awater zo nabij Oude Kerkje, Kortenhoef, The Netherlands

1997 One Line Drawing, Ubu Gallery, New York, USA

1996 The Dutch Connection Marshall Art Gallery, Memphis TN, USA

1996 Weatherview Norwich Gallery, Norwich, UK

1994 The Collection Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1994 De keuze van Betty van Garrel Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The

Netherlands

1993 Atelier Mémoire, Paris, France

1993 20 Years Wetering Gallery Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1993 Kai,Sagaert et Oudshoorn Atelier Mémoire, Paris, France

1992 Le Génie de la Bastille Paris, France

1992 Gemeente Kunstaankopen 1991 Museum Fodor, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1990 Liberations Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1989 Kunstlijn Sculpture Route Zwolle-Emmen, The Netherlands

1989 AMRO Bank Collection, A Choice Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The

Netherlands

1988 Spiel der Uberraschungen der Europaïschen Kunst des 20 Jahrhundert,

Bochholt, Germany

1986 KunstRai, Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1984 De Kampanje, Den Helder, The Netherlands

1981 Felison op Beeckestijn, with Marlene Dumas, Velzen Zuid, The Netherlands

1979 Van Krimpen Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1976 11 Painters, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1975 Markt 17, Enschede, The Netherlands

1974 Rijksmuseum Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands

Collections

Akzo Nobel Art Foundation

Collection Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

ABN AMRO Art Collection

The Chadha Art Collection

Eleanore De Sole Collection

Joods historisch museum

University Medical Center Utrecht

Collection Sammlung Schroth, Germany