Exhibitions

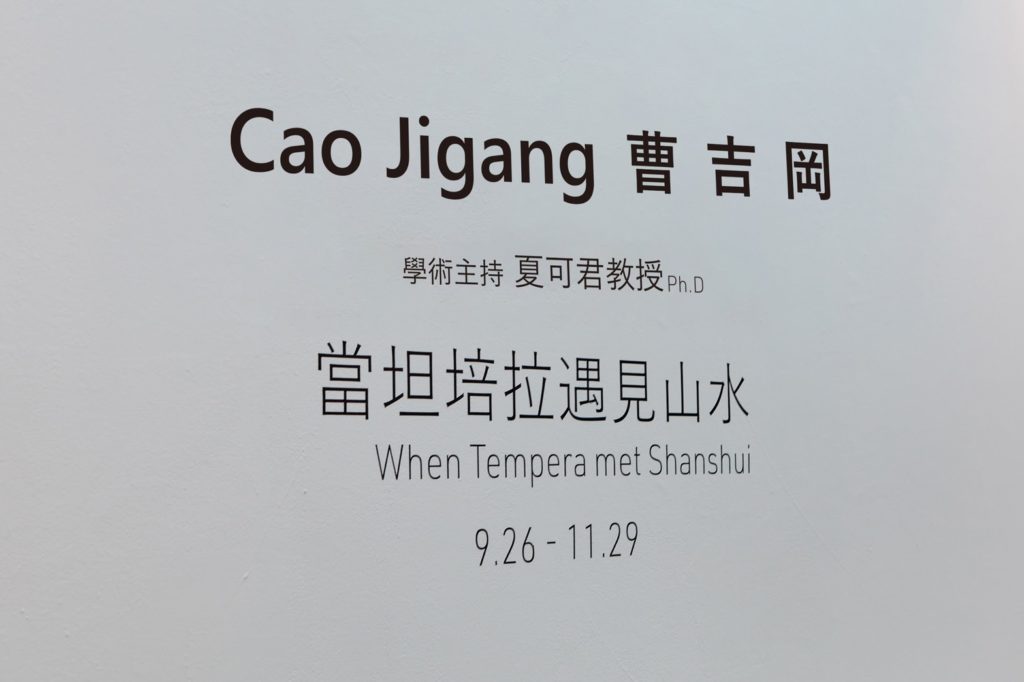

Bluerider ART 代理藝術家曹吉岡Cao Jigang「當坦培拉遇見山水」When Tempera met Shanshui 首個展,學術主持夏可君教授Ph.D ,9月24日於Bluerider ART[台北·敦仁]舉辦媒體記者會,9月26日正式開幕,並舉辦開幕三方學術會談「玉映世界:自然的當代詩意」主持人:夏可君教授Ph.D ,與談人:藝術家曹吉岡、Bluerider ART 執行長Elsa Wang。獲得與會嘉賓一致好評,並創下開幕直播觀賞高人次。

「當坦培拉遇見山水」

When Tempera met Shanshui

曹吉岡Cao Jigang首個展

展覽論述

Show Statement

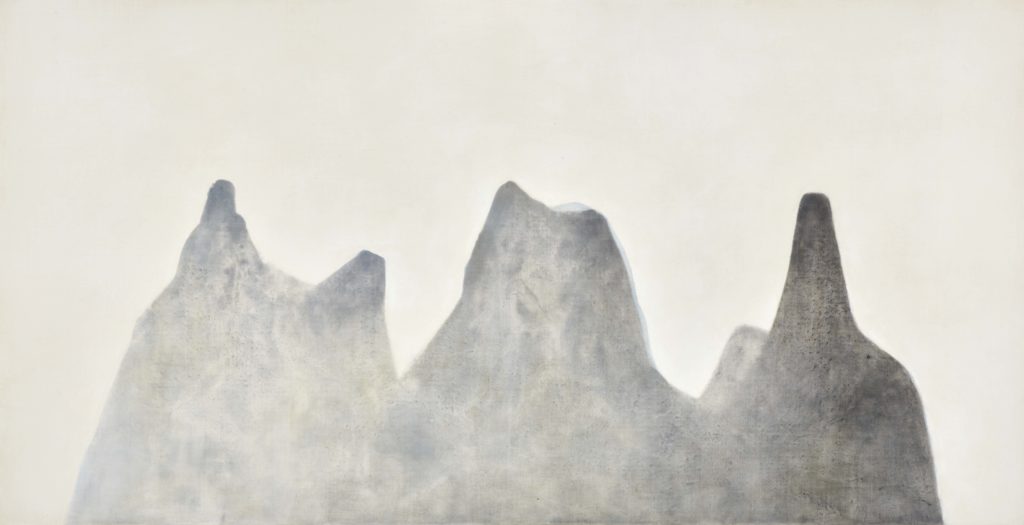

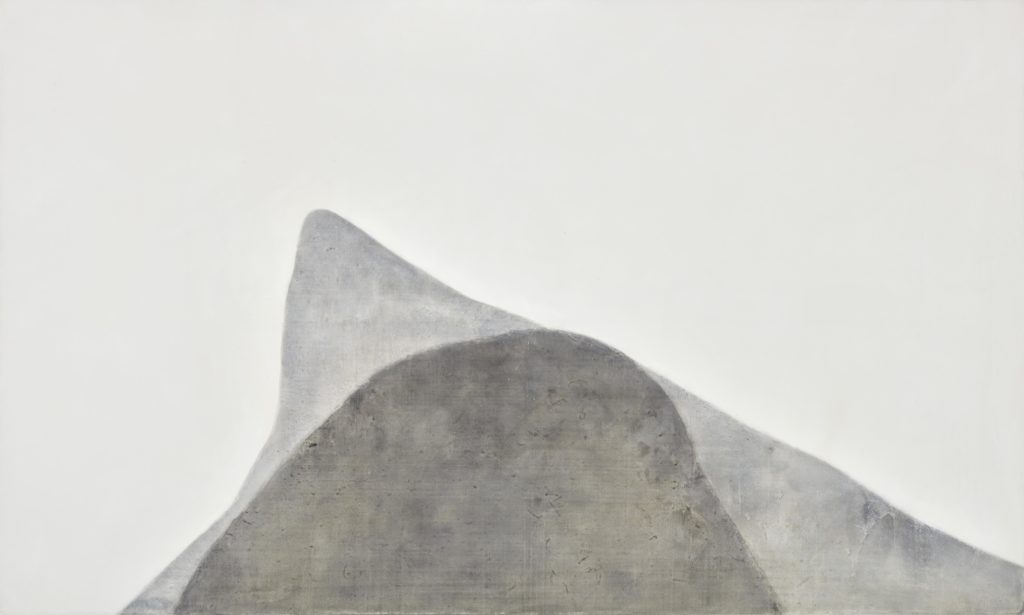

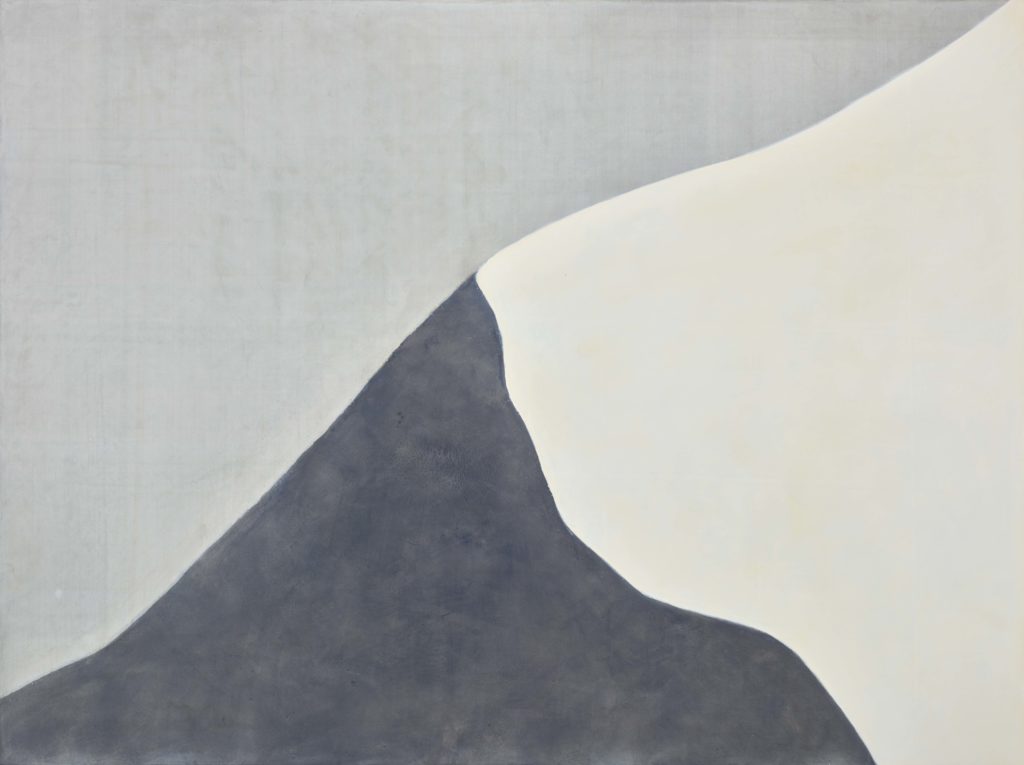

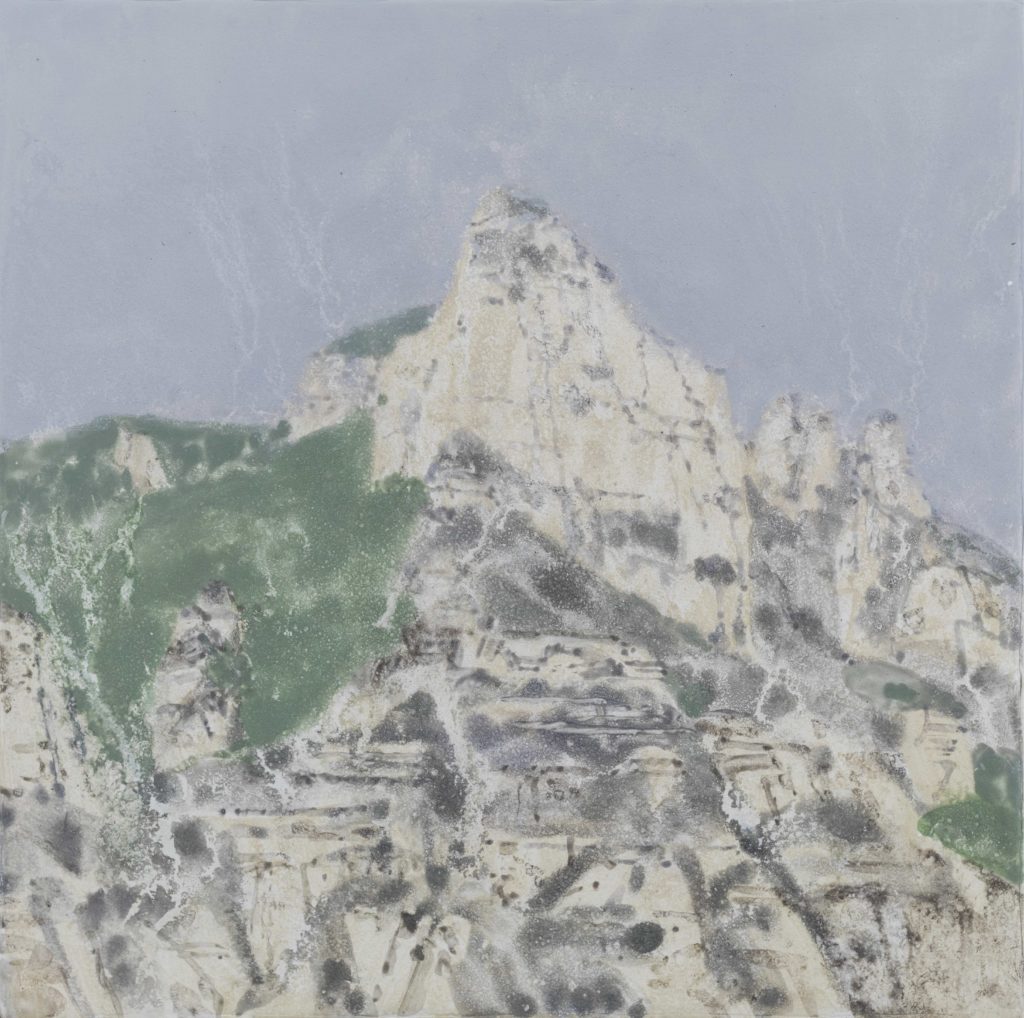

曹吉岡使用歐洲古老的坦培拉技法來創作,他把西方的古典技法通過東方玉質觸感與宋瓷的色感改造後,形成為多重深度的新山水。坦培拉(Tempera,義大利語)是一種源自於拜佔庭、歐洲古典時期及中世紀的繪畫技法。使用色粉與油、水混合的乳化劑,或與蛋黃混和調勻(通稱蛋彩畫)。此媒材的表面隨著時間而變得堅靭不變質,經過幾個世紀也無瑕疵。在反覆塗抹下,畫面呈現稀薄、半透明的效果,常使用在極高的描繪精細度上,擁有較低的顏色飽和度,呈現曖曖內含光的通透光澤感。在歐洲繪畫史上常用於壁畫、木板上的精細繪畫,14-15 世紀的義大利藝術家喬托(Giotto di Bondone)、波堤切利(Sandro Botticelli)的作品皆使用此媒材歷久彌新。

坦培拉的特殊性質在於它是一種乳液結合劑,含有油和水兩種成分,多使用蛋黃或全蛋為乳化劑,然後打入適量的亞麻仁油和樹脂油。穩定、牢固,最能保持顏料的鮮艷度,壽命比其它畫種(包括油畫)長。坦培拉因為顏料速乾的特性,藝術家作畫前畫布製作打底耗時費工,作畫時必須多層連續快速作畫,具有一定高難度,直到15世紀油畫盛行而逐漸式微。曹吉岡改造坦培拉的繪畫技法,並保留一層層的製作打磨過程,但又借鑒水墨罩染的方式,保持間薄余留的痕跡,卻又豐富了玉質的觸感。坦培拉的透明畫法與水墨罩染形成的一道道透明的痕跡,非常迷人,帶來審美的「感知的深度」。

回顧中國山水畫的興起受到道家的觀點與思想的激發,「與自然合一」的觀念流行在詩人及畫家之間。宋元的山水畫,本身就是一種孤獨與沈默的藝術,充滿精神上的莊嚴與肅穆之情,有別於「風景畫」,山水藝術是富有精神性的。面對自然的寫生中,融入傳統山水畫的圖像記憶,尤其是局部的片斷被融入到當前的直接觀看中,形成藝術圖像記憶「歷史的深度」。他認為寫生的好處就是直接面對自然,在特定時間內把畫完成。有種即興的、生動的東西在裡面,會很快地進入對對象的一種本質的研究,更可以把想要的東西很快地抓住。

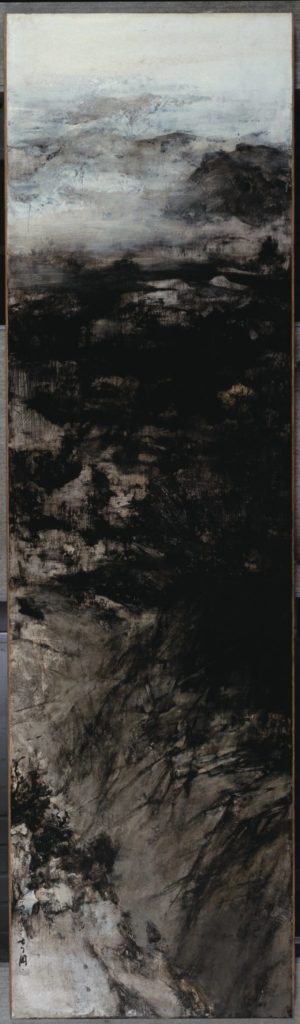

中國山水畫是以心理狀態為主宰,去描繪山水空間的美學,是脫離現實的約束,以心映畫。曹吉岡說:「幸好中國有山水畫這樣一個畫種,不然我等蓬萵之人如何安放自己那雖然卑微卻又不可出賣的靈魂?這也是山水畫兒在當代殘存的一點兒自我拯救的價值。躲進小樓,不管秋冬。」 早期作品《廣陵散》刻意與現實保持距離,而這種巨大的疏離感持續地延續至今的創作。傳統山水畫是一個「可居可游」的理想世界,他的畫中沒有任何路徑供觀者進入,它與人和社會保持著距離,它是現實生活的對立或稱反象,是一片沒有溫度的風景,冷漠、嚴峻,沒有慾望。曹吉岡遁逸至中國山水畫中便是一種解放的方式。如此一來,沒有批判地對抗世界,而選擇在山水風景中,找到避世之道。沒有古代文人嚮往桃花源的閒情逸致,而是一種隔絕疏離的無人之境。

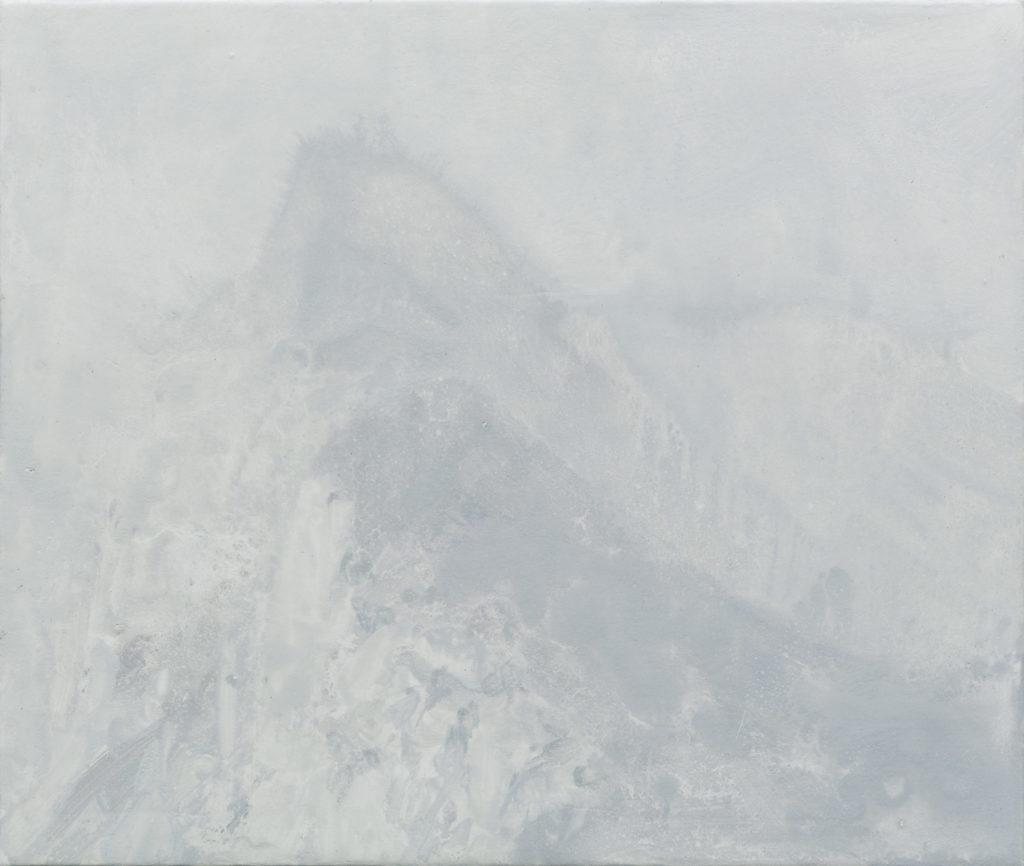

曹吉岡的創作理念,認為傳統水墨畫的虛空是留白,是不畫,是以「無為」來表現虛空的概念,但他反其道而行,使用坦培拉經過十幾遍甚至幾十遍的「有為」塗抹,一層層虛薄的材料在乾燥的時間過程中沈積下來,這樣形成的虛空有了結實的觸摸感、物質感和厚重感,形成一種「實體」的、從「有」中而來的「無」。面對強大的傳統山水,他只取極少的元素融進風景中,生成不同於兩者的疊加態。這種疊加態是西方畫法的堅固性與傳統水墨的流動性之間的一種平衡,形成了文化識別上的模糊性。這種模糊性比確定性,打開了更大的思維與想像空間。曹吉岡認為不必用東方或西方的畫法結構去看待他的作品,它只是兩種表達方法、兩種藝術混生而成的另一種畫面的呈現。坦培拉作為成全虛無水墨的方法,介於抽象與具象之間,這是他刻意打造的模糊文化識別趣味。簡化為宋代禪意山水的淡遠,幾乎去除了自然山水的意象,如同一抹時光的淡痕,淡遠悠然。這是「意境的深度」。畫面上黑白灰的處理,尤其是黑白的切分,形成至簡又極強的對比 。這是「色覺的張力」。曹吉岡的平面繪畫與古典文人美學的空間有著深度契合,但這是繪畫極簡思維轉化之後,所啓動的幽微又悠遠的「冥想空間」。

2020 年 Bluerider ART 「當坦培拉遇見山水」When Tempera met Shanshui -曹吉岡首個展,同時邀請知名中國藝術評論家夏可君教授Ph.D 擔任學術主持。藝術家曹吉岡將展出近年最新創作,表達他的內心世界:「元代詩人倪雲林在他的路上踽踽獨行,進入了極端個人化的」花不開水不流的寂寞世界」。我希望能沿著這條路繼續前行,抵達一個沒有花沒有水的更加荒寒空寂的無人之境。」

歐洲坦培拉

展場實景

媒體預覽 9.24

專訪

開幕學術會談9.26

【玉映世界:自然的當代詩意】

主持人:夏可君教授Ph.D 與談人:藝術家曹吉岡、Bluerider ART 執行長 Elsa Wang

Artists

曹吉岡 Cao, Jigang

(China, b.1955)

出生於北京,1984年畢業於中央美術學院油畫系,2000 年畢業於中央美術學院油畫系材料表現研修組。曾任教於中央美術學院造型學院基礎部。曹吉岡的作品融合東西方美學,用混生方式表現中國山水畫中的「虛空」。

知名中國藝術評論家夏可君教授Ph.D 談論曹吉岡作品:「曹吉岡的坦培拉作品乃是連接自然與生活,西方古典與中國古典,傳統與當代,現實與夢想之間的仲介,是在趙無極與朱德群的抒情風景抽象之後,華人藝術家所給出的另一個新階段,這就是古典山水畫的歷史記憶與西方古典的手法觸感,經過新的極簡主義與虛薄化轉換,更為具有東方典雅高貴的氣質與生命洗心的精神。」曾多次於中國美術館及海外展出,榮獲第九屆全國美展銀獎(1999)並由中國美術館、 上海美術館…等永久收藏。

曹吉岡的創作理念,認為傳統水墨畫的虛空是留白,是不畫,是以“無為”來表現虛空的概念,但他反其道而行,使用坦培拉經過十幾遍甚至幾十遍的“有為”塗抹,一層層虛薄的材料在乾燥的時間過程中沉積下來,這樣形成的虛空有了結實的觸摸感、物質感和厚重感,形成一種“實體”的、從“有”中而來的“無”。面對強大的傳統山水,他只取極少的元素融進風景中,生成不同於兩者的疊加態。這種疊加態是西方畫法的堅固性與傳統水墨的流動性之間的一種平衡,形成了文化識別上的模糊性。這種模糊性比確定性,打開了更大的思維與想像空間。曹吉岡認為不必用東方或西方的畫法結構去看待他的作品,它只是兩種表達方法、兩種藝術混生而成的另一種畫面的呈現。坦培拉作為成全虛無水墨的方法,介於抽象與具象之間,這是他刻意打造的模糊文化識別趣味

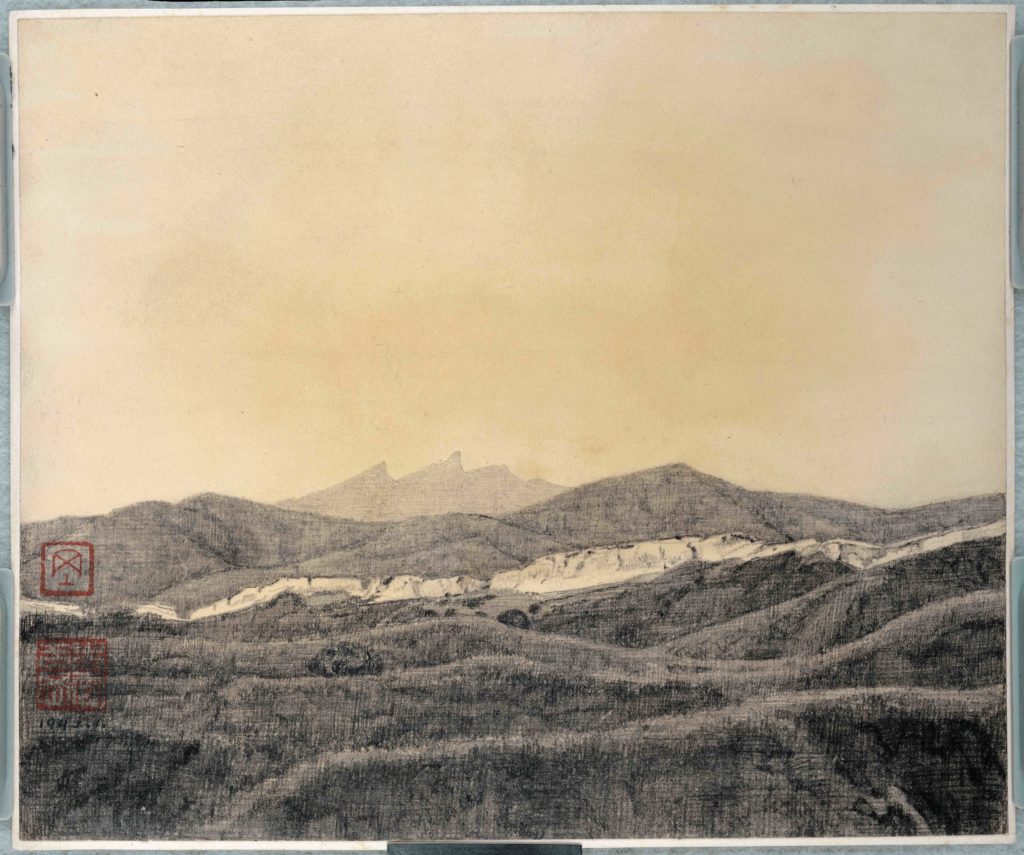

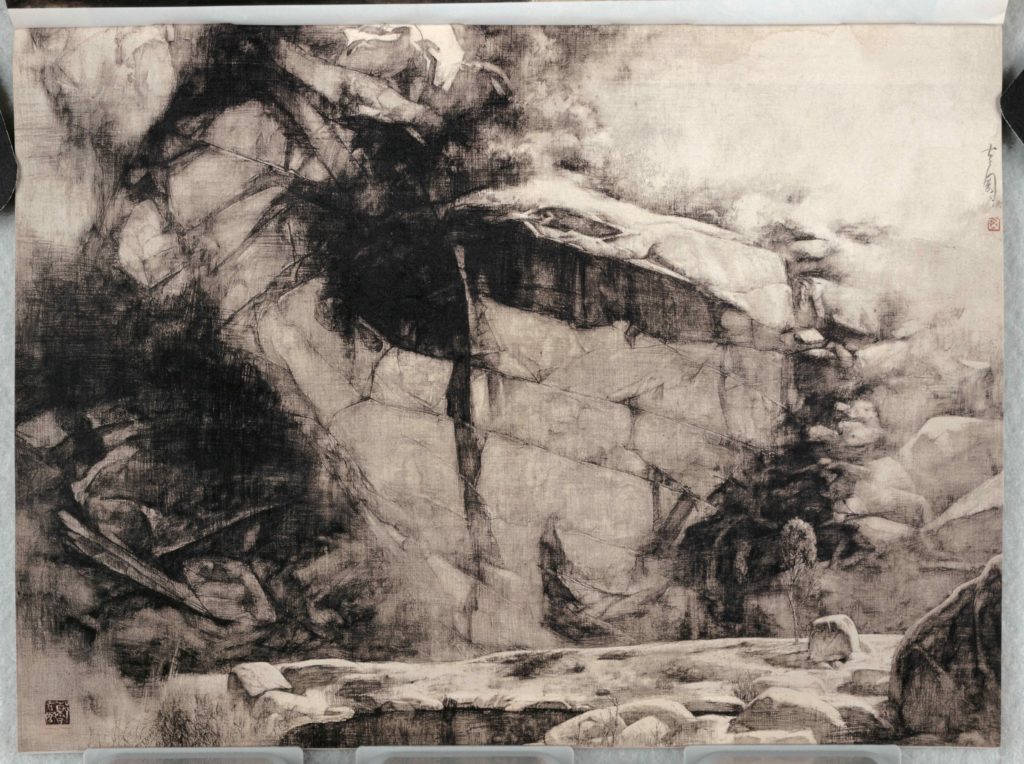

1984年自中央美院畢業至今,歷經幾個創作時期。最初以油畫寫生為主,這時期以一系列長城油畫,表達歷史廢墟的蒼涼。轉折時期以鉛筆素描表現水墨的氣韻質感。後一個時期再,以丙烯進行創作。接著進入坦培拉十年研究時期,以7米巨幅坦培拉作品「廣陵散」為此時期代表。近期2020于Bluerider 首個展創作走向更極簡抽象精神性的表達。

曹吉岡Cao Jigang 不同時期創作

第一階段 – 油畫 長城系列

轉折期 – 鉛筆素描油畫

炳烯時期

寫生作品

2000年 坦培拉時期

Education

1984 中央美術學院油畫系

2000 中央美術學院油畫系材料表現研修組

Selected Exhibitions

2018 十五章·曹吉岡作品展 築中美術館

2015 曹吉岡小作品展,築中美術館,中國北京

2014 空寒,自然的虛托邦,索卡藝術中心,中國北京

2014 抽象與自然,築中美術館,中國北京

2013 墨以象外—中美藝術家聯展,中國美術館,中國北京

2012 當代—中國油畫雙年展,中國美術館,中國北京

2012 跨躍極限,紐約天理藝術中心,美國紐約

2011 付出與獲得,科羅拉多大學美術館,美國洛杉磯

2009 悟象化境—傳統思維的當代重述,中國美術館,中國北京

2008 「象」之中國—曹吉岡階段回顧展,中國美術館,中國北京

2008 平遠—中央美術學院五人展,今日美術館,中國北京

2007 對應:應對—2007中美藝術家作品交流展,中國美術館,中國北京

2004 首屆中國北京國際雙年展,中國美術館,中國北京

2001 杜勒與中國山水的對話—曹吉岡紙上作品展,索卡藝術中心,中國北京

1999 第九屆全國美展(《蒼山如海》獲銀獎),中國北京

1998 中國山水畫油畫風景展,中國美術館,中國北京

1994 新鑄聯杯中國畫、油畫精品展(《深谷淺溪》獲銀獎),中國美術館,中國北京

1992 曹吉岡畫展,中國美術館,中國北京

Awards

2014 《獅子林》獲法國美協沙龍展金獎

1999 《蒼山如海》獲第九屆全國美展銀獎

Beijing Fine Art Exhibition For 50th Anniversary of Funding PRC – “蒼山如海”-outstanding award

1991 《深谷淺溪》獲新鑄聯杯中國畫、油畫精品展銀獎

Press