感謝

The Art Scape

London Art Roundup

報導

|The Art Scape|

MARCK’s Playground at Bluerider ART

By Fiona Doyle – April 4, 2024

Bluerider ART, a progressive gallery, was founded in 2013 by Taipei-based IT entrepreneur Elsa Wang. It launches it’s 2024 Programme by expanding its Artistic Footprint with its new Mayfair Gallery in London.

Bluerider ART has launched its inaugural exhibition of the year, MARCK’s Playground, a solo exhibition of work by multidisciplinary Swiss artist Marck In its newest gallery space in Mayfair, London. This will be the Marck’s first solo show in the UK in over a decade.

Bluerider ART has set its sights on the vibrant art scene of London, having successfully established two galleries in Taipei’s city centre and a prominent presence in The Bund, Shanghai, in 2021, Bluerider ART. Positioned as a cultural hub that resonates with art enthusiasts, collectors, and international visitors, this new Mayfair space is located at 47 Albemarle Street.

This expansion marks a significant milestone for Bluerider ART, which is known for its commitment to fostering artists’ self-expression across various art forms, with a distinct focus on the convergence of technology and art.

MARCK’s Playground presents a series of strikingly inventive and mesmerising video works, framed in the context of the artist’s signature handcrafted sculptures. It runs 14 March – 26 May 2024.

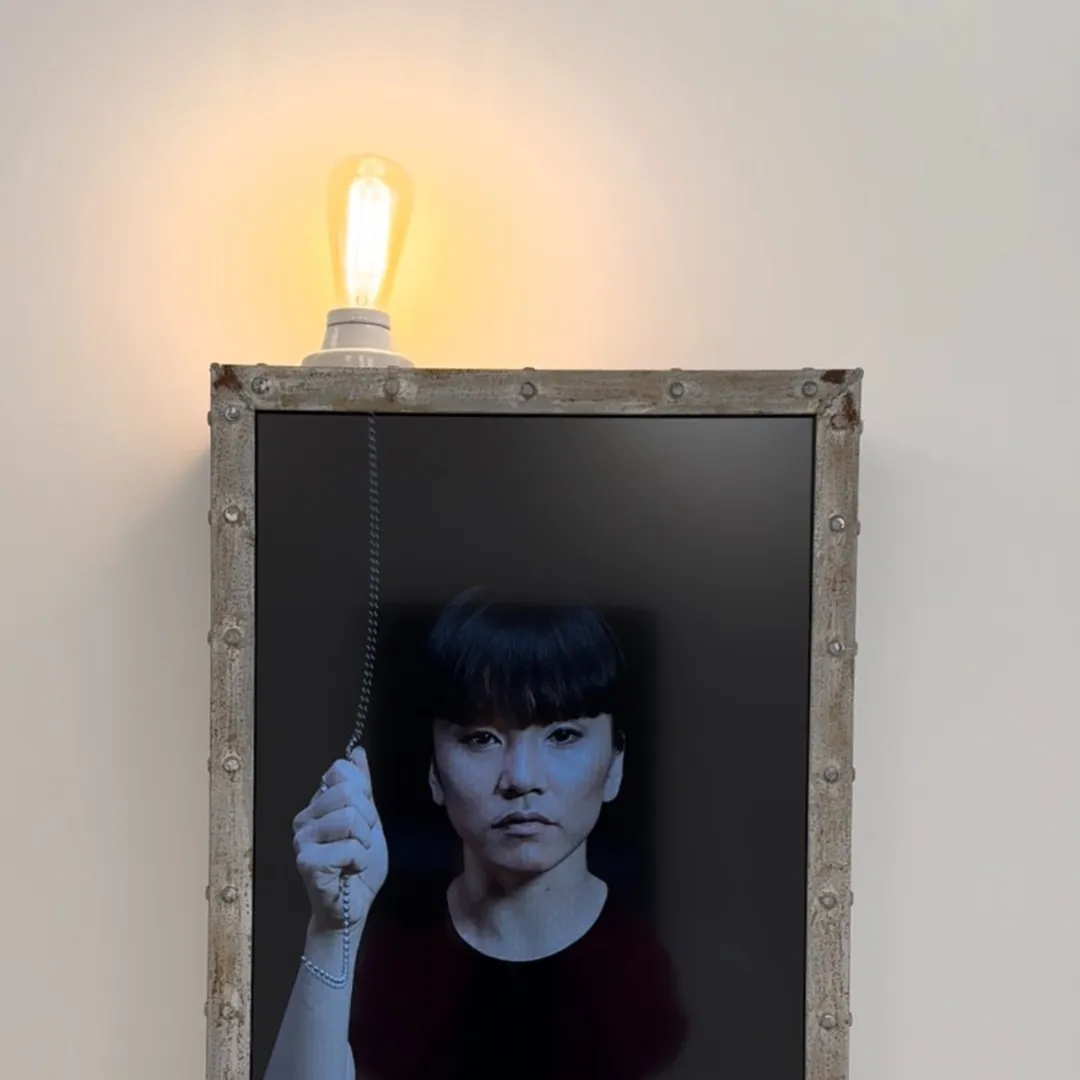

Renowned for his experimental works in video sculpture, March’s work has been exhibited globally. His work frequently portrays women, sometimes struggling or confined in narrow spaces. The works address societal issues through themes such as hope and hopelessness, frustration and faith, freedom and grace.

The artist’s use of sculpted metal frames to confine his videos function as metaphors for the boundaries women face in society, pointing to further questions around voyeurism and human interaction.

Artistic innovation and sensory delight converge in MARCK’s Playground. The works serve as a journey through which to experience a variety of psychological scenarios.

Marck’s large-scale classic work Gegenstrom depicts a woman swimming in slow motion, expressing a desire for survival and exploration.

Gegenstrom – 2024 (107x65x23cm) – Wood aluminium player screen

Clockwork combines video and kinetic installation, provoking feelings of anxiety in its showcase of avoidance dynamics between a woman and a pendulum; while Phone Connected presents an innovative manifestation of global social network connections and contemporary social modes.

Clockwork 2024 – 110x65x21cm- Iron gear motor player screen

These video sculptures represent a societal microcosm, reflecting the physiological and psychological states of modern individuals across various social strata, navigating familiarity and unfamiliarity, and grappling with identity in time and space.

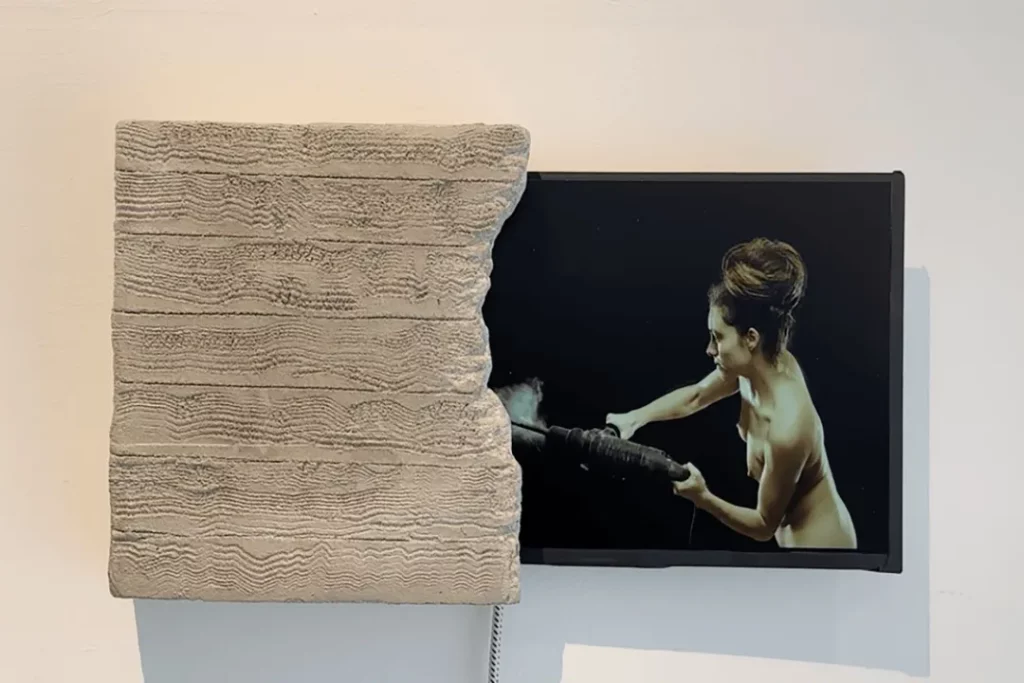

Furthermore, the collision between subject and frame unfolds under multiple layers of constraints, illustrating how modern individuals traverse the boundaries of survival and respond to the limitations of existence – casting these questions towards the audience to inspire both resonance and imagination.Marck’s unique approach to the combined disciplines of video and sculpture is in many ways informed by his unconventional artistic journey. While he initially enrolled in a prestigious, traditional art school, he soon left to engage, instead, in a series of diverse occupations, from auto dismantling and mechanical electrics to rock music and tech installation design. Marck also acknowledges deep influences from Fluxus member Nam June Paik, as well as Wolf Vostell, considered one of the pioneers of video art. For Marck, technology is both a means and a purpose, meant not to narrate a story but to evoke an emotion through a distinction between the virtual and the real.Dreams that burst – 2024 (74x131x9.5cm) Wood color screen player electronics

Speaking of the work, Swiss art historian and critic Dr. Andres Pardey tells us: “Interpretations may vary, with some viewing through a lens of objectification, while others analyse the visuals for signs of oppression and constraints.

The diverse perspectives, ranging from open acknowledgment to clandestine observation, contribute to a unique interactive interpretation process involving the artist, the artwork, and the audience. Marck’s direct engagement with the external challenges and pressures faced by women in his works releases a spectrum of emotions, making his art profoundly meaningful.”

In addition to Marck’s exciting video sculptures, Bluerider ART invites visitors to gain a unique and immersive insight into the artist’s practice, with a site-specific studio installed within the gallery space.

Audiences are encouraged to interact with and explore Marck’s creative working process in the playground, where the artist will also draw inspiration from his observations of local life, incorporating features and facets of the neighbourhood into his on-site creations.

MARCK’s Playground runs at Bluerider ART London: 47 Albemarle Street, London W1S 4JW from 14 March to 26 May 2024.

|London ART Roundup|

Swiss artist Marck is an artist whose work I’ve wanted to see in person for quite some time. His artwork is a hybrid of video timed to coincide with the movements of physical, kinetic sculptures. The results are highly engaging, often playful visuals that look great on social media and I was excited at the opportunity to finally experience them firsthand. Maybe my expectations had been set too high, but I left disappointed. I’ll explain why, but first let’s discuss what’s good.

In the 60s and 70s, video technology became small and affordable enough to enable artists to experiment. Early adopters like Wolff Vostell, Nam June Paik and Tony Ousler notably treated video not as the final artistic output, but simply as one of many elements to be incorporated into their work, like paint or clay. Vostell buried TV sets within his abstract canvasses, Ousler projected video of faces onto sculptural figures to bring them to life, and Nam June Paik famously created a Family of Robot made from antique radios and television sets.

Despite those early works showing such exciting potential most “video art” you will encounter is likely to be a single screen presentation that adheres to widely recognised TV formats: documentary, short-form narrative or voice-over accompanied by visuals. If you can get the same experience watching it on YouTube as you can in a darkened gallery then it’s not video art, it’s just video. I suspect Marck agrees. He’s the only contemporary artist I’m aware of that consistently explores how video can be incorporated as a physical component of a sculptural work, thereby transforming and redefining both.

His series that initially caught my attention features the silhouette of a figure stuck behind the screen, slowly feeling their way around the edges and trying to push their way out. In various iterations the screen might appear to be a large fish tank or the panel of a shipping crate. In one incredibly claustrophobic version the display slowly rotates, forcing the silhouette inside to awkwardly tumble around as if they were inside a rectangular hamster wheel.

Marck has incorporated water, light, sound and moving elements into his works and seeing them in person was absolutely better than watching a clip on social media but as I mentioned, two things let me down.

The first was something I couldn’t have anticipated: some of the production looked poorly made. Mind you, not everything. I was blown away by “Split no. 4 2021/2022” in which a women appears to spit water out of the video screen into an upturned horn. The effect was seamless, and it was impossible to tell where the water pumps and controls had been hidden. But then some works, like “Gegenstrom”, looked like household aluminium foil had been quickly applied to the display frame which distracted from, rather than enhanced, the intended effect.

The other issue was something I should have anticipated had I been properly paying attention to his back catalogue: the majority of the work was overtly, and unnecessarily, sexualised. “Human Watch” is a fascinating piece whereby digital clock numerals get re-drawn every sixty seconds by figures who move in and out and in of the LCD boundaries. There’s no need for them to be naked other than to titillate. ‘Patriarchat’ is even more egregious. A woman with a giant jackhammer is enclosed inside half of a cement panel, showing her cutting her way out (or in?). She’s completely naked except for a hard hat, and I suppressed a laugh as an old Seinfeld episode ran though my head, which has a discussion about what is ‘good naked’ (sitting on the sofa reading the newspaper) and what isn’t good naked (coughing or using a belt sander).

It was disappointing and distracting to see so many interesting concepts filled with female objectification. (Men rarely appear.) Physically squeezing people into a sardine can might not be the most subtle metaphor, but it’s still a powerful image that could have been made even more fascinating through the use of video. Filling it with naked women squeezed together and titling it “Sex Sells” reduces the concept to crass schoolboy humour.

I’ve got nothing against nudity in art, and artworks generally aren’t considered overly sexualised or pornographic when nudity is used in the service of the intended message. One easy way to check is to visually re-imagine the work with the nude removed or covered up. If the message becomes confused, then the nude was clearly integral and justified. If the message hasn’t fundamentally changed, then you have to wonder why it was included in the first place.

Far too many of Marck’s works left me wondering, which was frustrating because the concepts inspired and excited me in ways that modern sculpture and/or video art rarely does.

〰