(Germany, b. 1970)

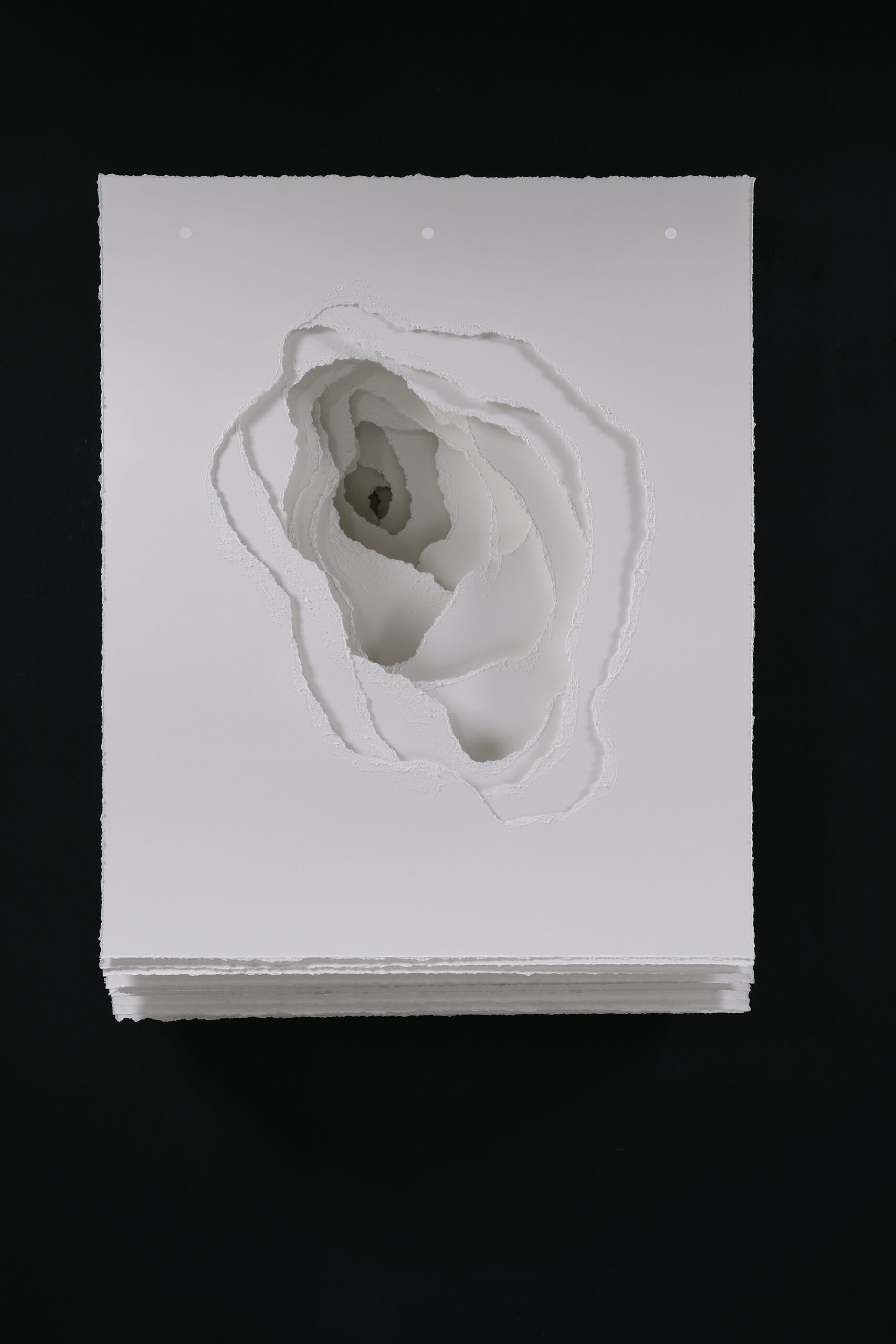

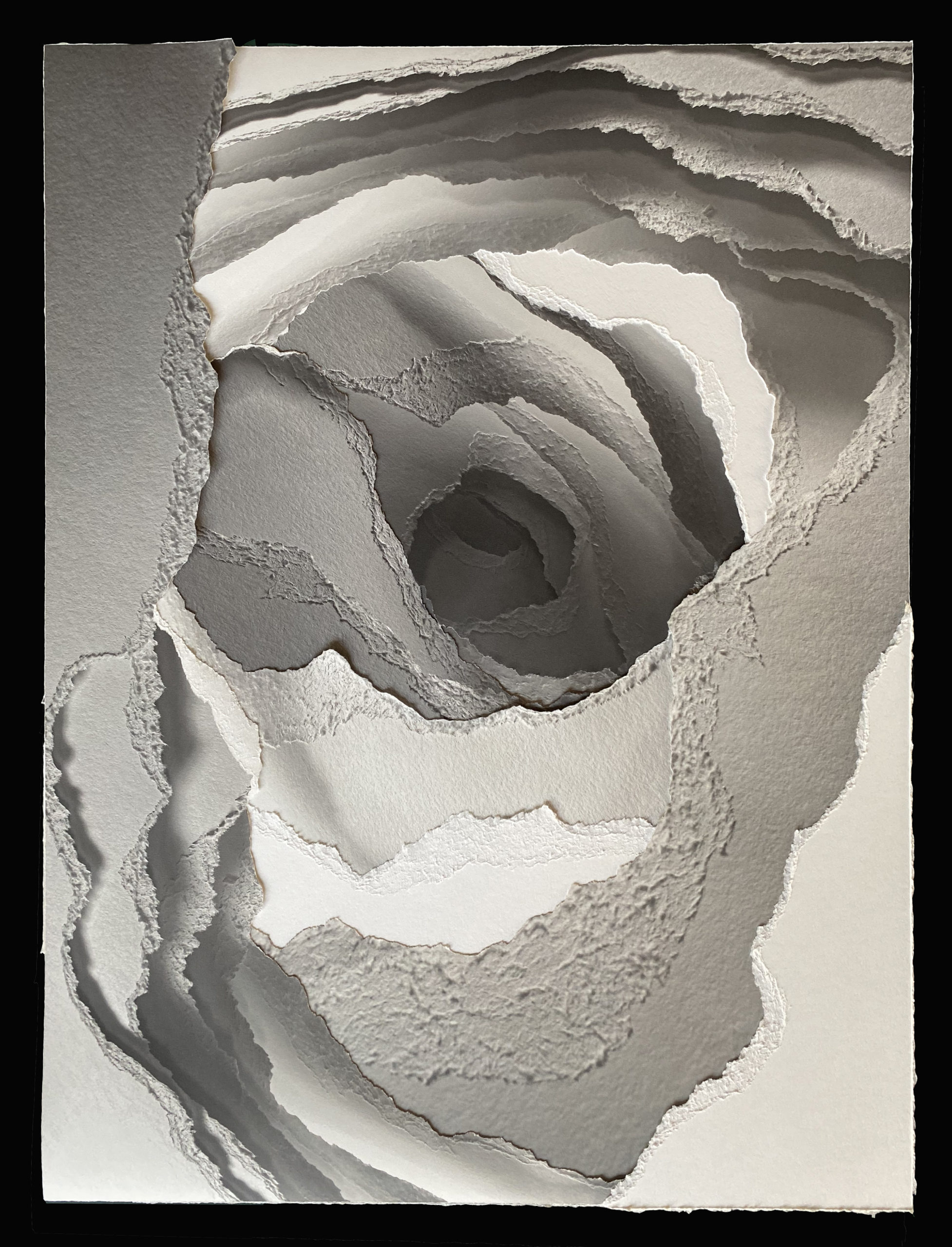

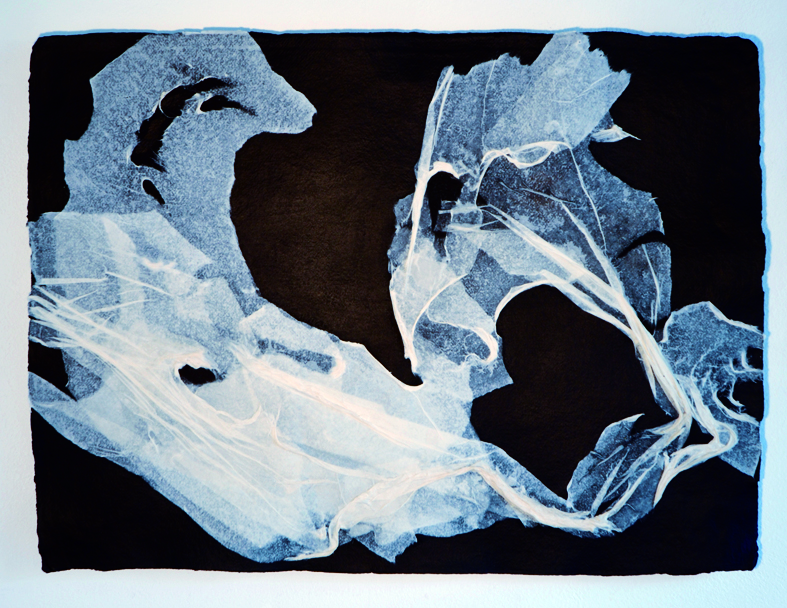

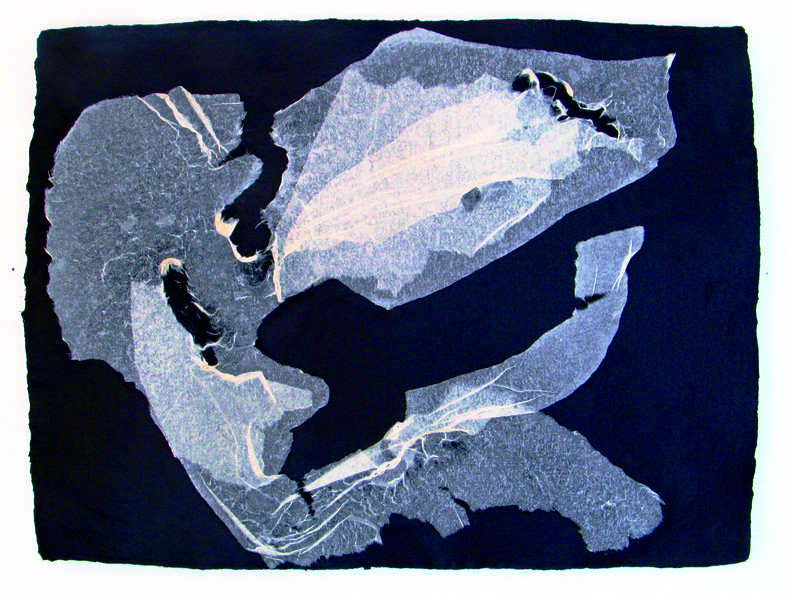

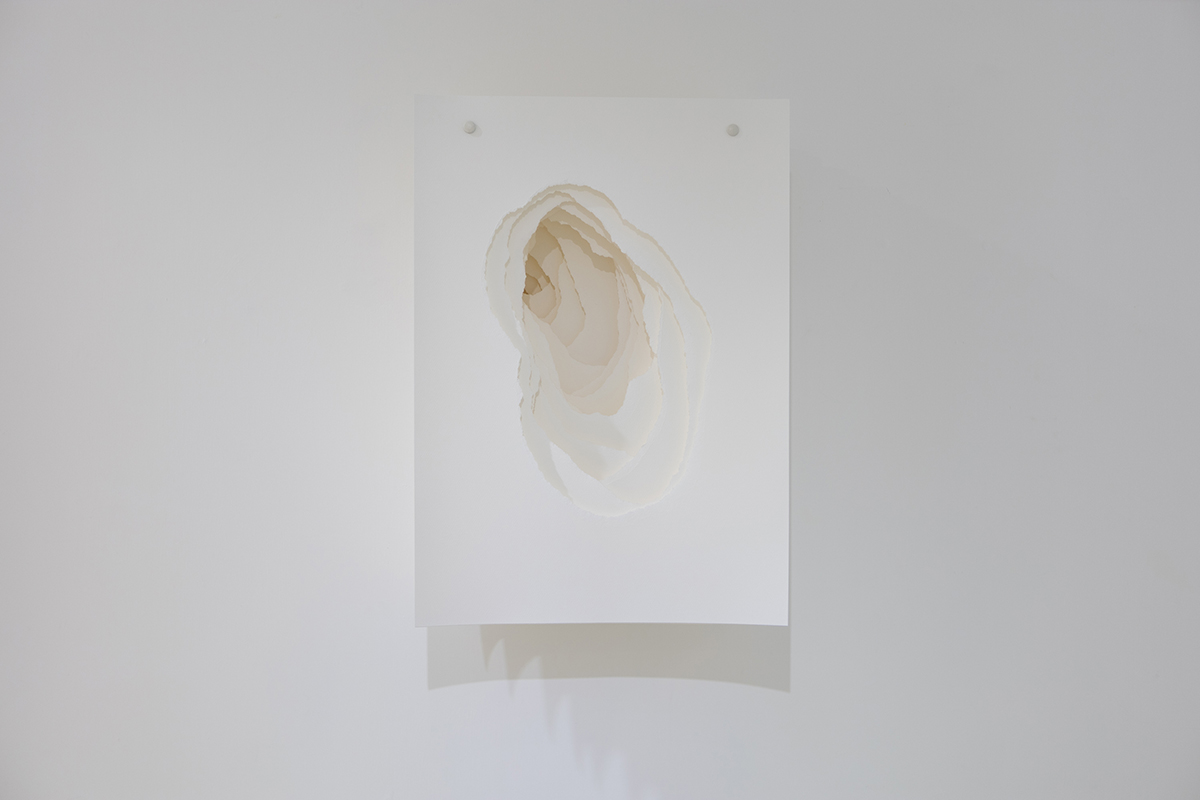

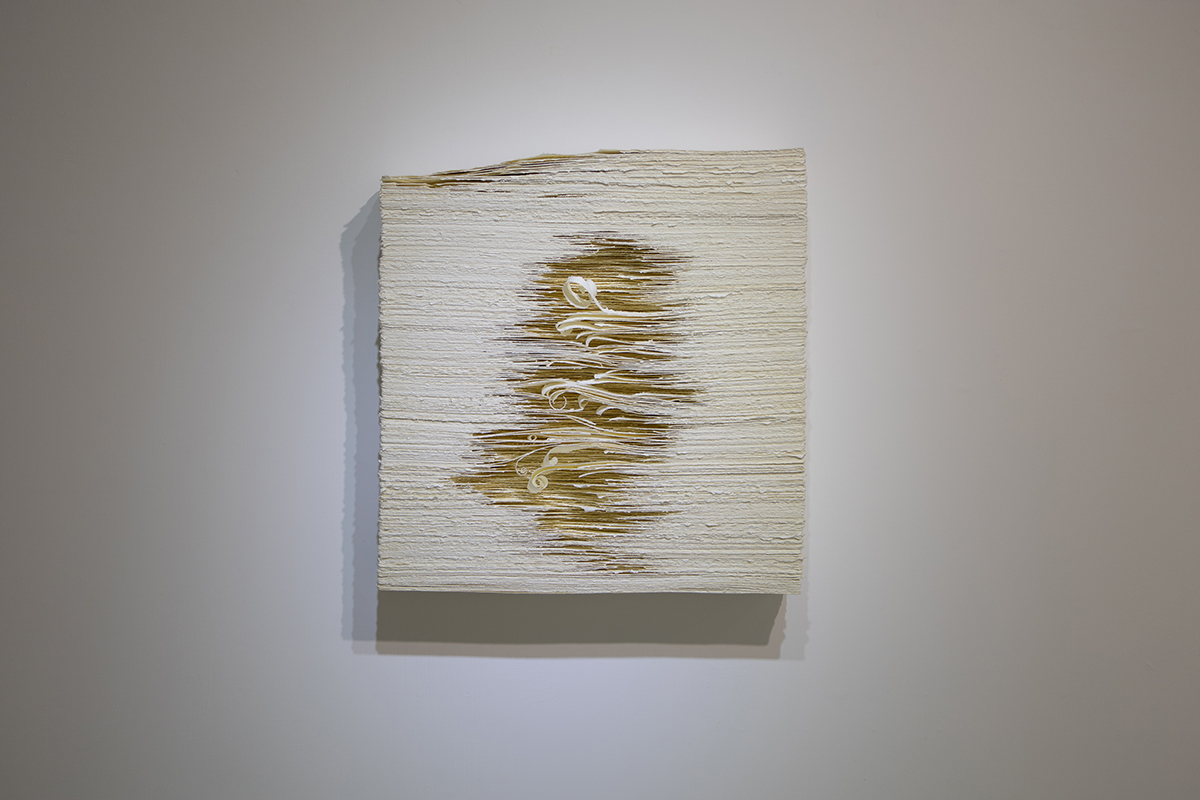

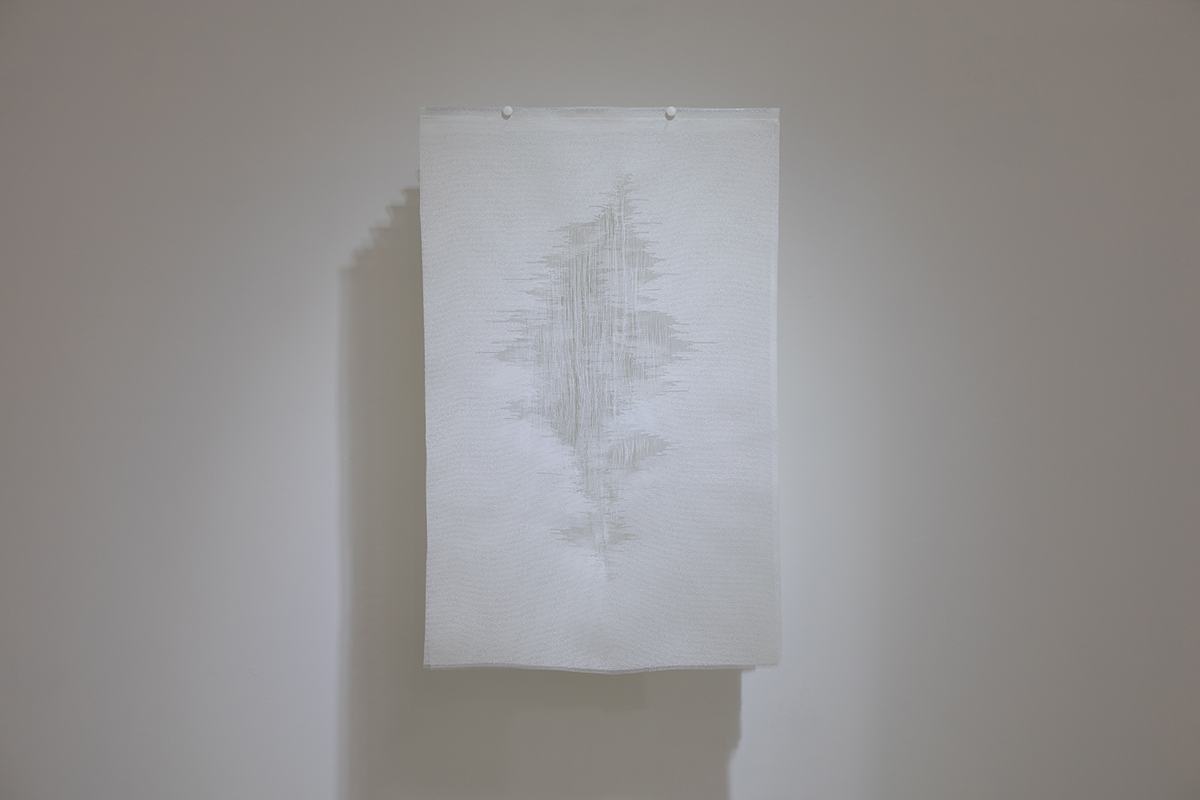

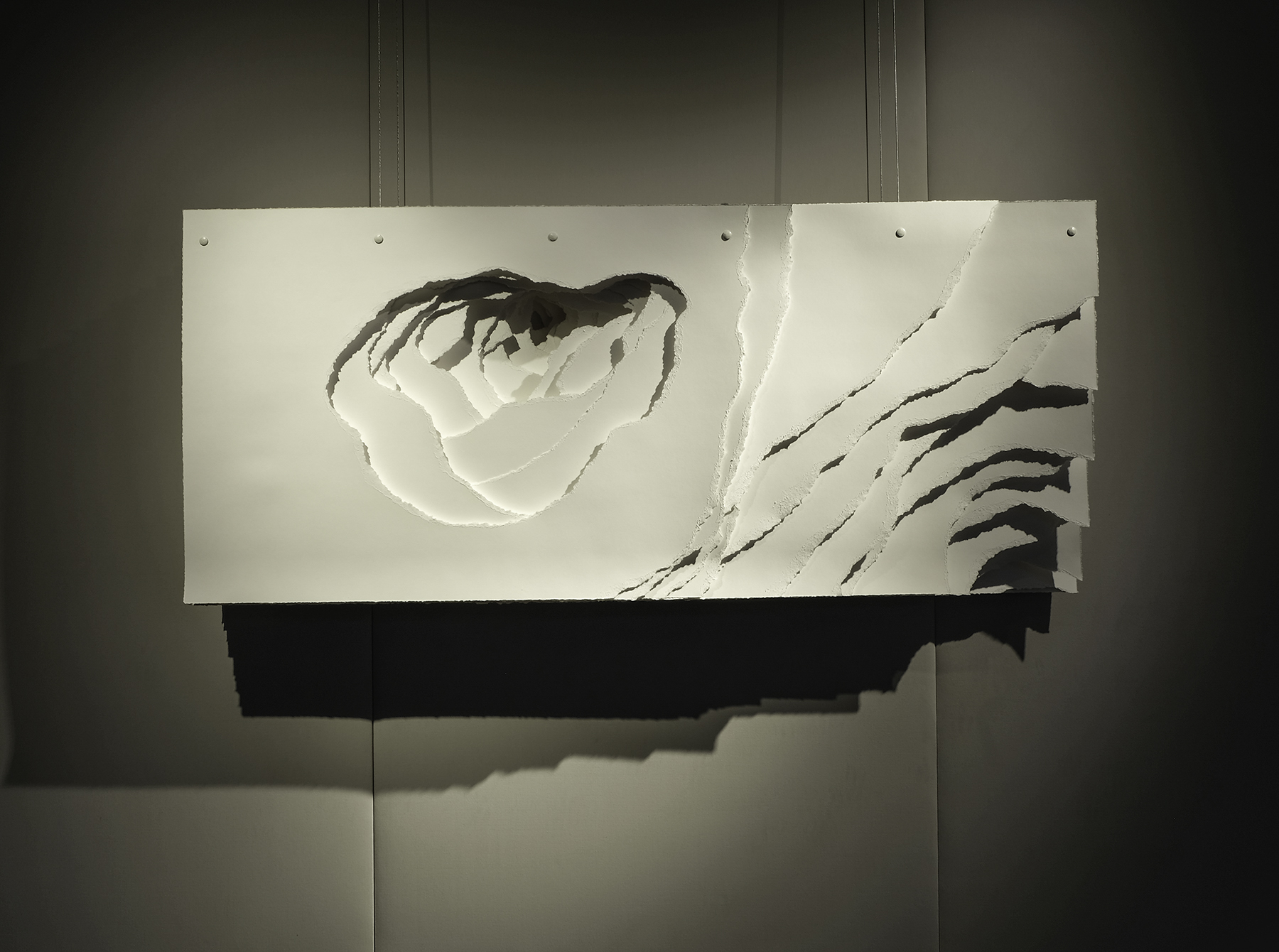

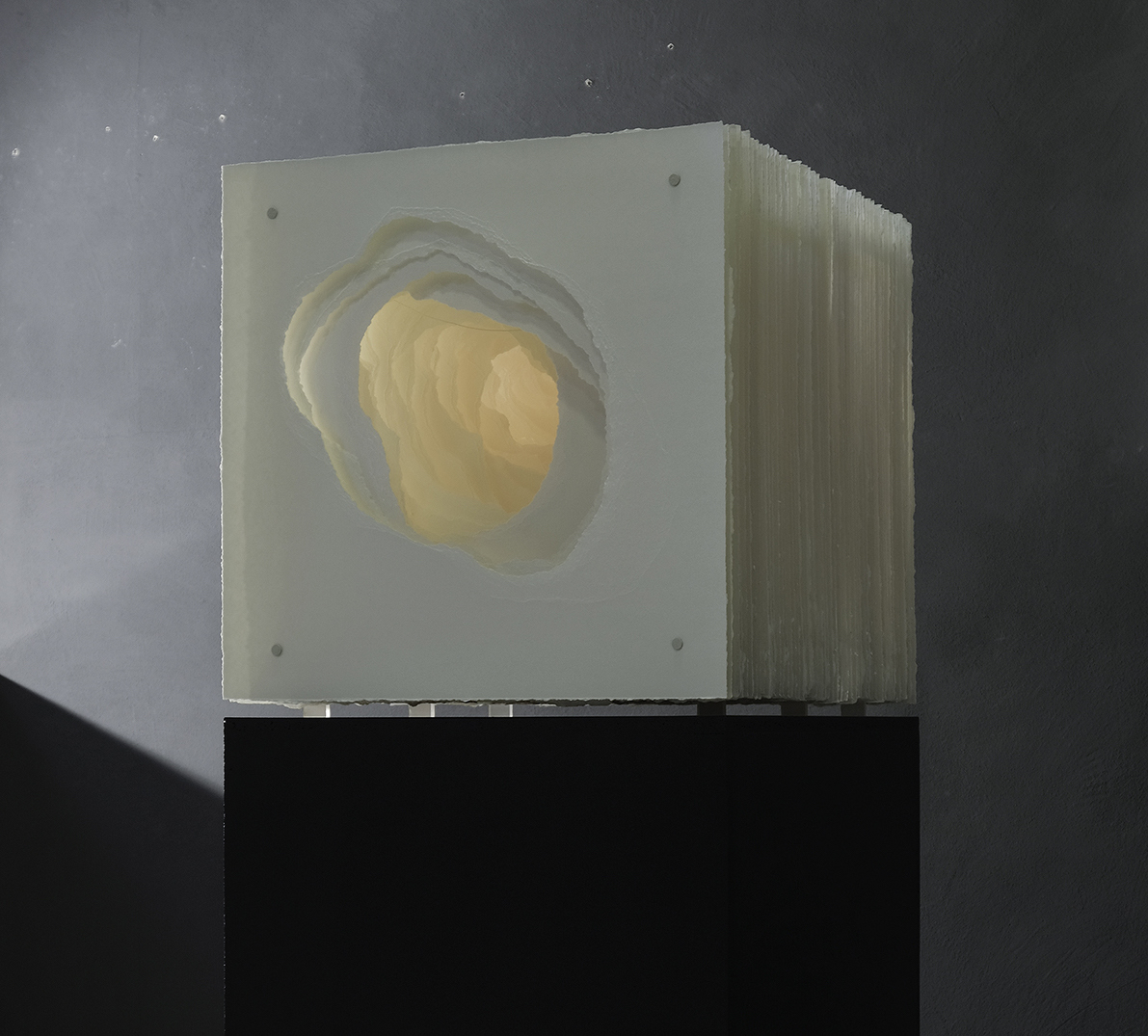

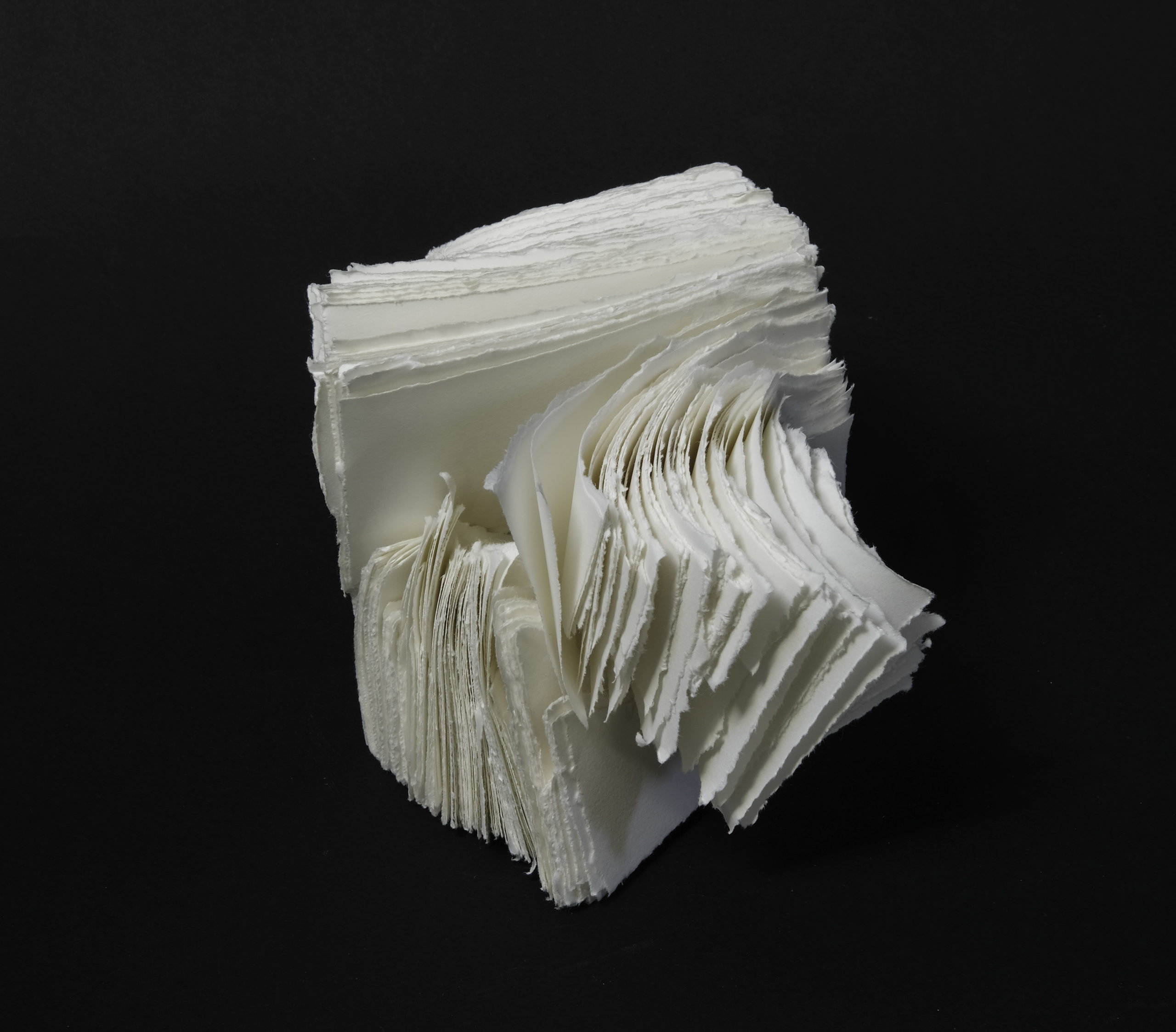

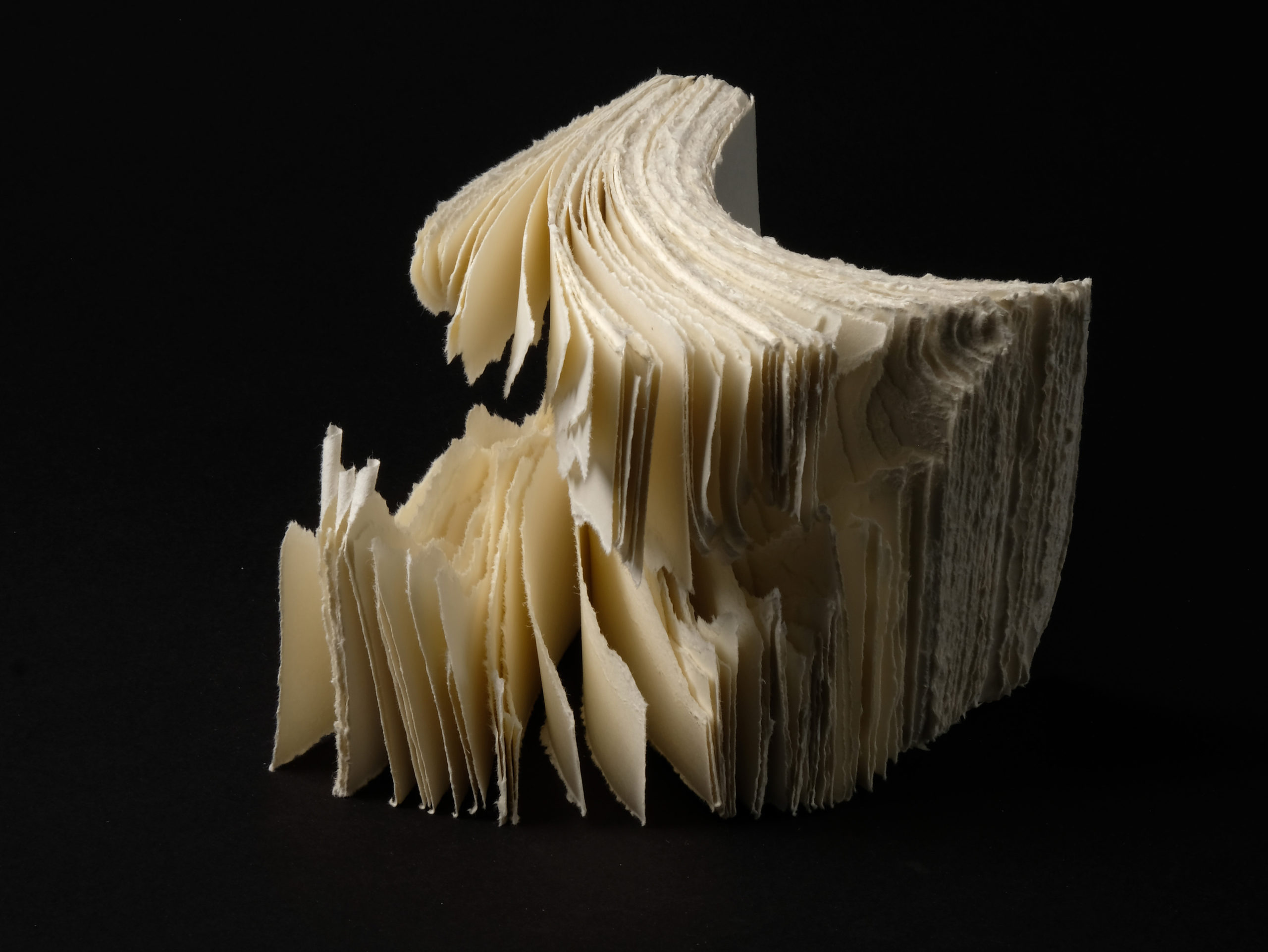

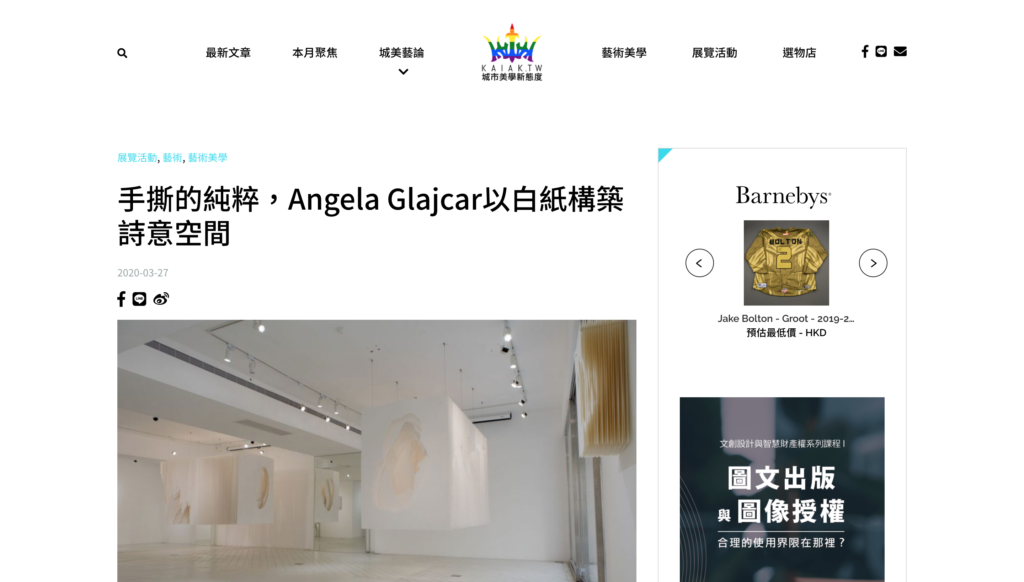

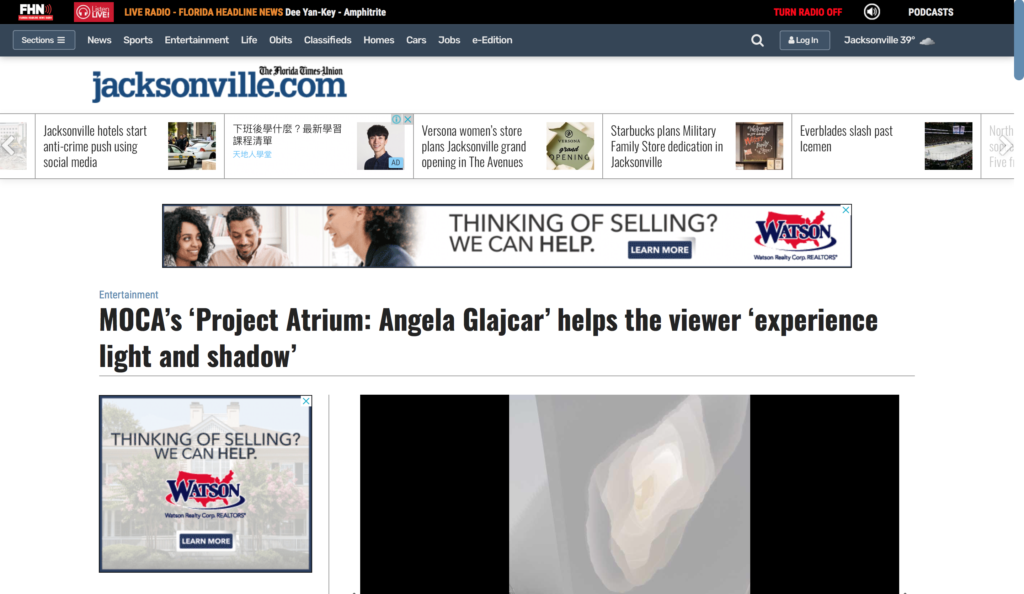

Born in Mainz, Germany, Angela Glajcar studied sculpture at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Nuremberg from 1991 to 1998. Glajcar's work embodies sculpture and installation, it examines the way in which space is experienced using a material that is fragile and light. In the act of ripping and perforating a material that is traditionally used as a two-dimensional support, Glajcar gives paper a strong sculptural presence. Terforation is the title of Angela Glajcar's famous cubic pieces. The staggered arrangement of the vertically hung series of sheets of white paper, with torn edges, produces cave-like recessions. These extend into the depth of the sculpture. The sharp ridges and deep caverns gives viewer a fascinating room of harmony and silence. Glajcar has exhibited extensively and been the recipient of numerous awards and fellowships including Studio Award of the Kunststiftung Erich Hauser, the Asterstein scholarship in 1999 and Vordemberge Gildewart Award in 2004. Glajcar's works have been showcased in various prominent public art exhibitions, including Cologne Cathedral, the Frankfurt Department of Culture, the Jacksonville Museum of Contemporary Art, and the Mainz Gutenberg Museum. Permanent collections of Glajcar's works can be found at the Jacksonville Museum of Contemporary Art in the United States, the Wiesbaden Museum in Germany, the Mainz Arts and Sciences Center in Germany, and the Hanten Schmidt collection in Austria.

The 11th From Lausanne to Beijing Fiber Art Biennale Excellence Award

National Museum Of Women In The Arts (NMWA) PAPER ROUTES

2022 Gustav-Lübcke-Museum, Hamm Germany Faszination Papier

2019 Lunar Sonata : Hanji Works and Contemporary Art, Jeonbuk Museum of Art South Korea

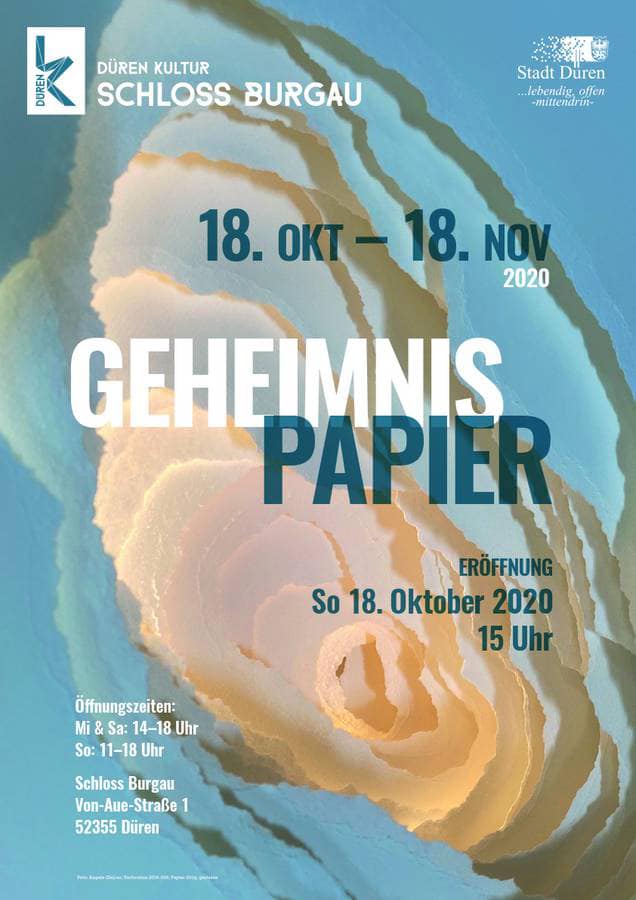

Museum Schloss Burgau GEHEIMNIS PAPIER Oct.18-Nov.18, 2020

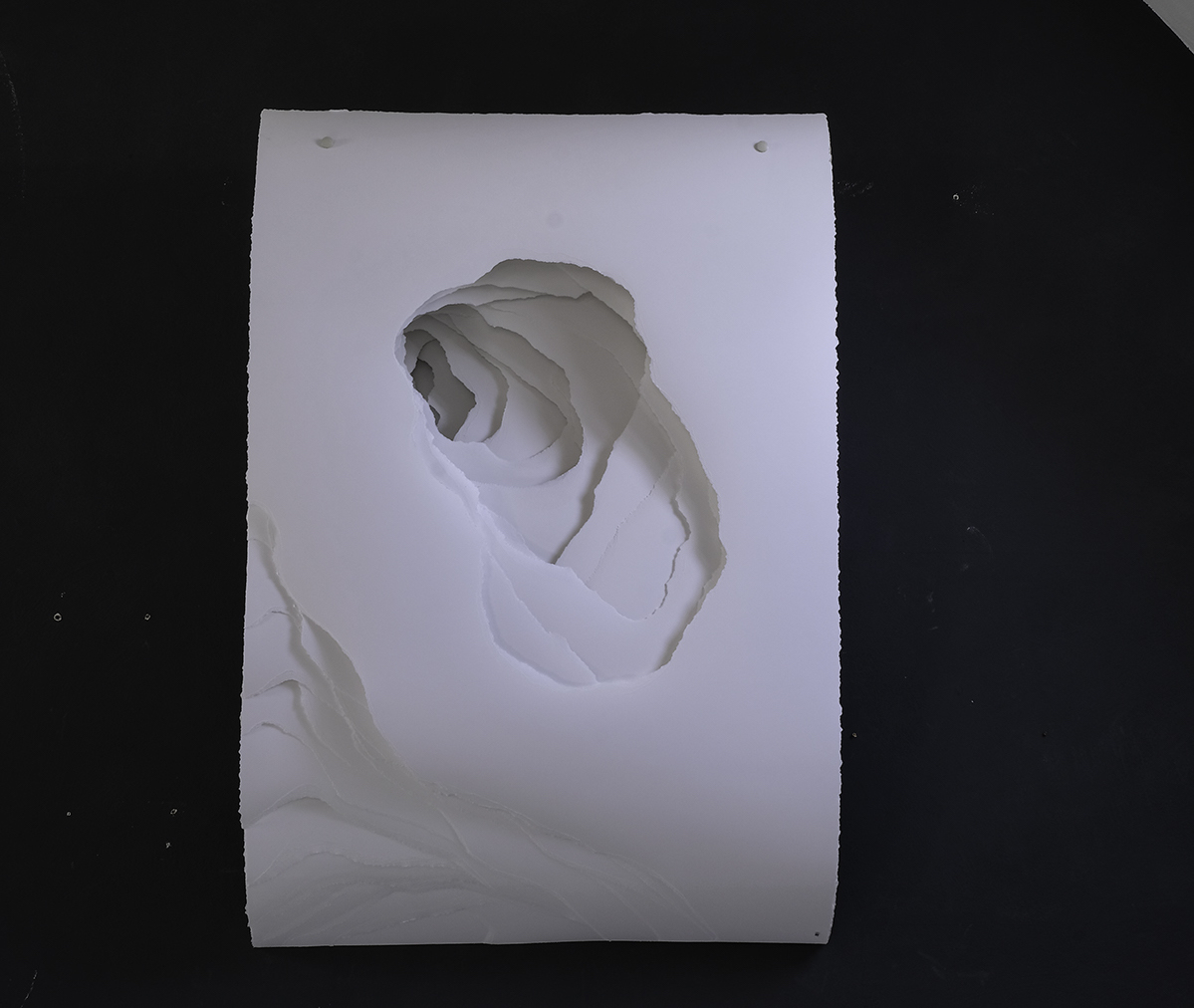

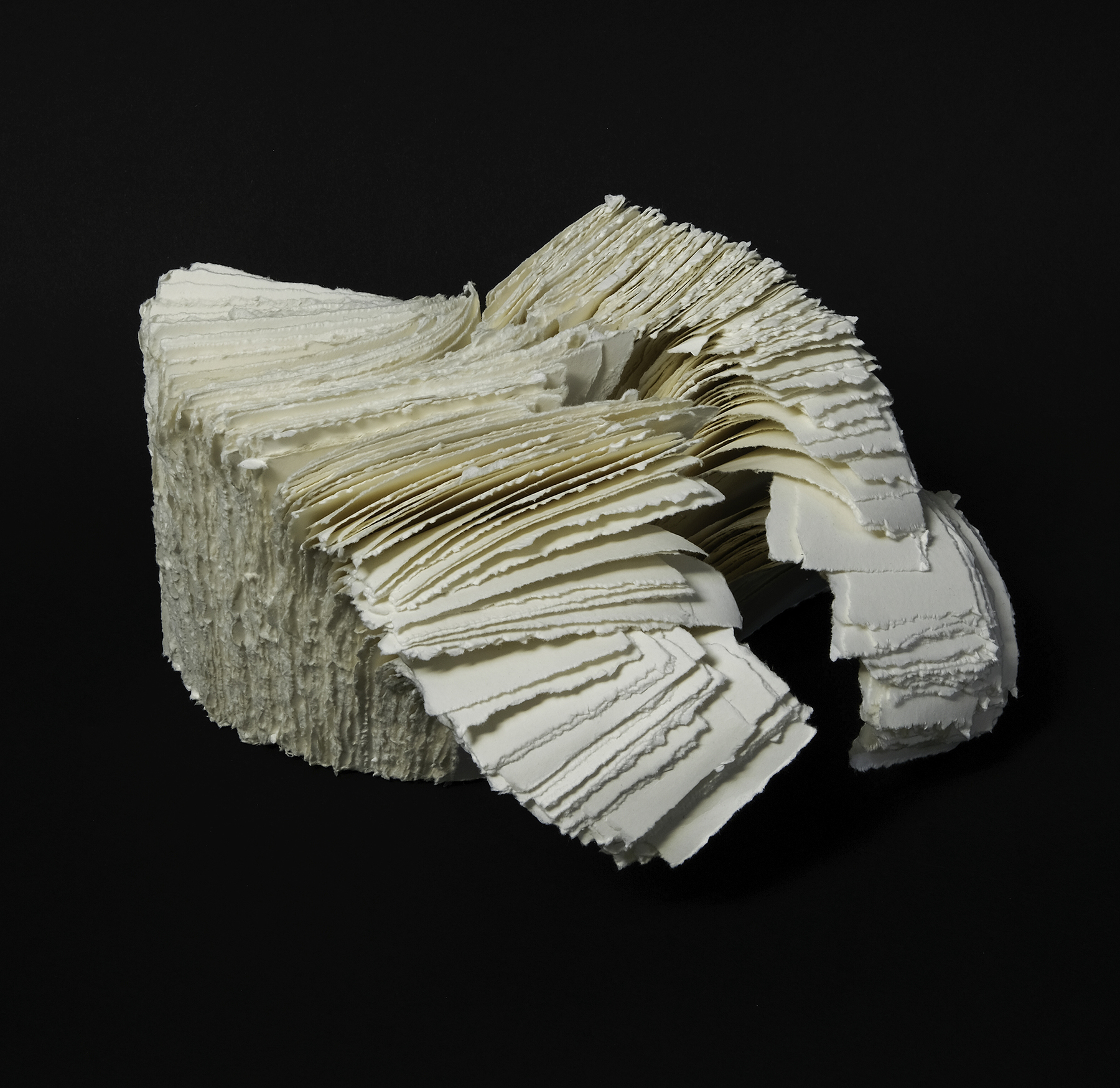

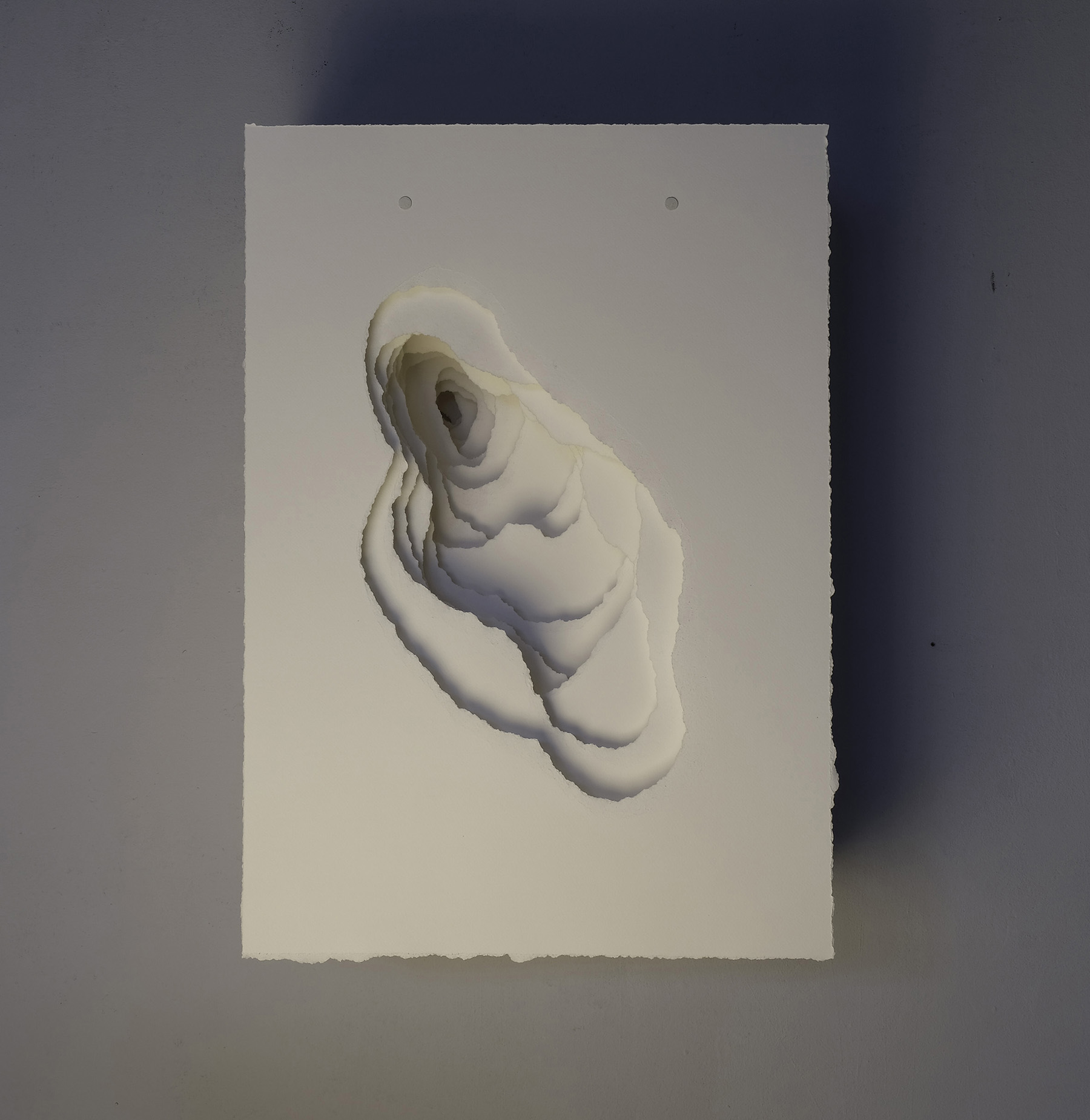

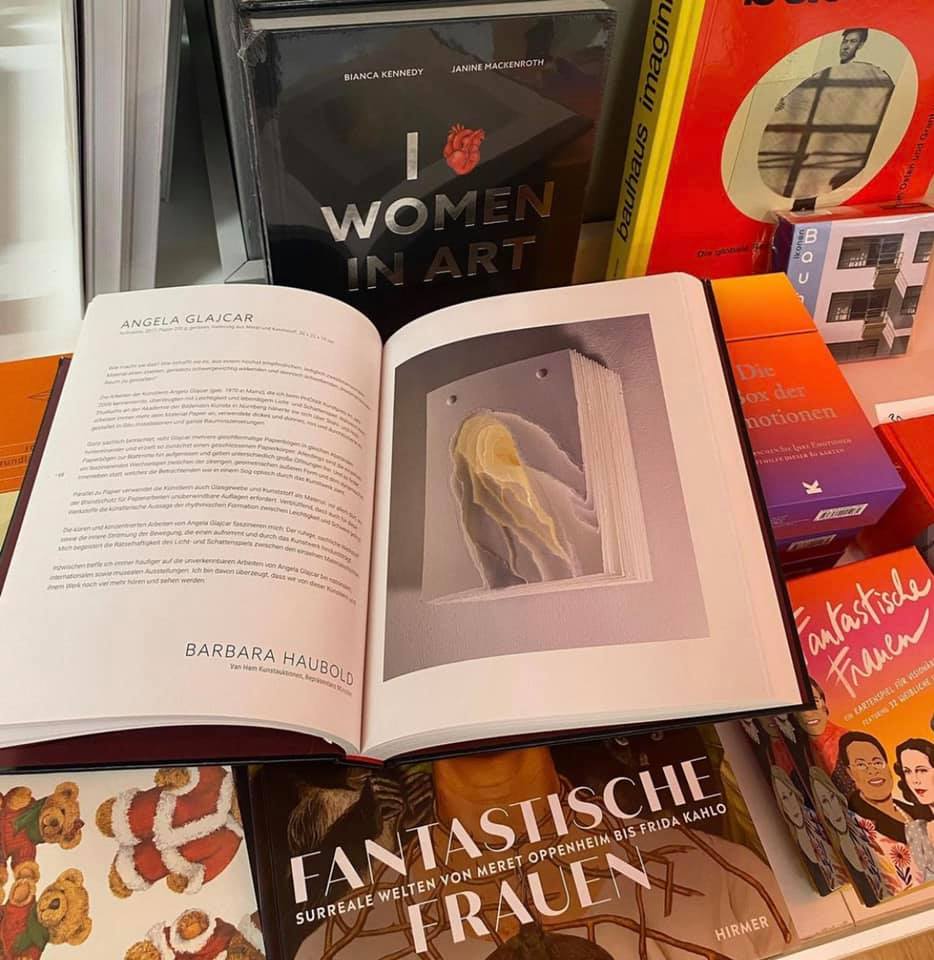

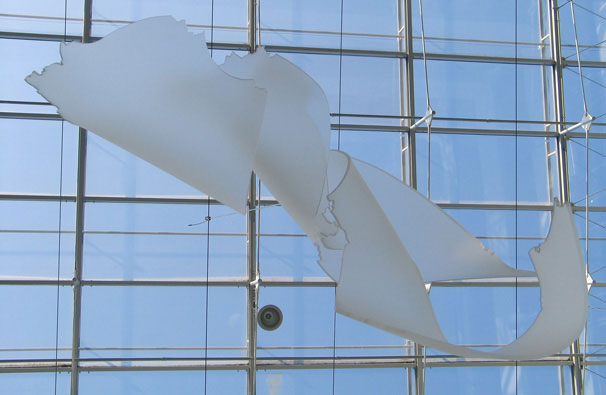

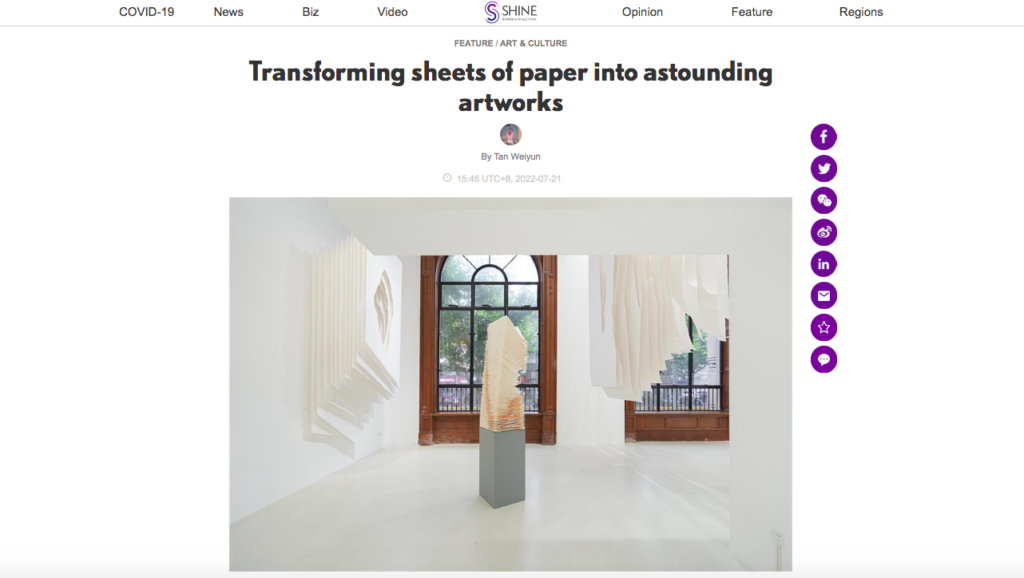

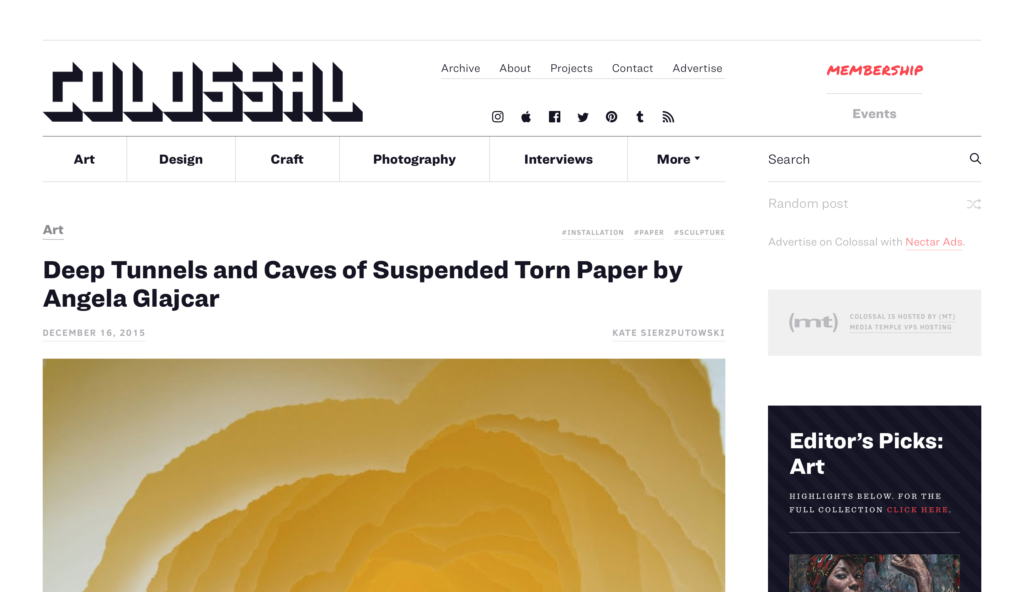

Glajcar's work embodies sculpture and installation; it examines the way in which space is experienced using a material that is fragile and light. In the act of ripping and perforating a material that is traditionally used as a two-dimensional support, Glajcar gives paper a strong sculptural presence. Her paper sculptures mostly hang, floating in the air. They seem light and delicate, however they show a strong sculptural presence. Terforation is the title of Angela Glajcar's cubic pieces. The staggered arrangement of the vertically hung series of sheets of white paper, with torn edges, produces cave-like recessions. These extend into the depth of the sculpture. The sharp ridges and deep caverns evoke associations with glacial or rock formations while light and shadow fall on the surface of the sheets, enlivening the interior of the oblong structure. The viewer is led into fascinating rooms of harmony and silence.

In the history of painting, paper is typically used as a medium, and artworks on paper are often viewed from a flat perspective, creating fictional perspectives. Paper can also be used as a material for sculpture. Picasso, for instance, cleverly used paper combined with line drawings to create three-dimensional sculptures, as seen in his work "Head of a Woman, Mougins" (1962). Angela Glajcar directly utilizes paper as a sculptural material, challenging traditional notions of its softness and imbuing it with changes in light and shadow, spatial rhythm, and weight.

In the realm of sculpture, Minimalism seeks to purify forms or colors. Artist Donald Clarence Judd (1928-1994) introduced the concept of "Specific Object" in 1965, reducing the influence of form or color to the utmost limit. The artwork is neither painting nor sculpture but a specific object, presenting the work in the present moment of "here and now." Glajcar's works, using a single material and monochromatic paper, emphasize the purity of paper. She further subverts this purity, introducing more variations in form and space, creating a dramatic effect for viewers.

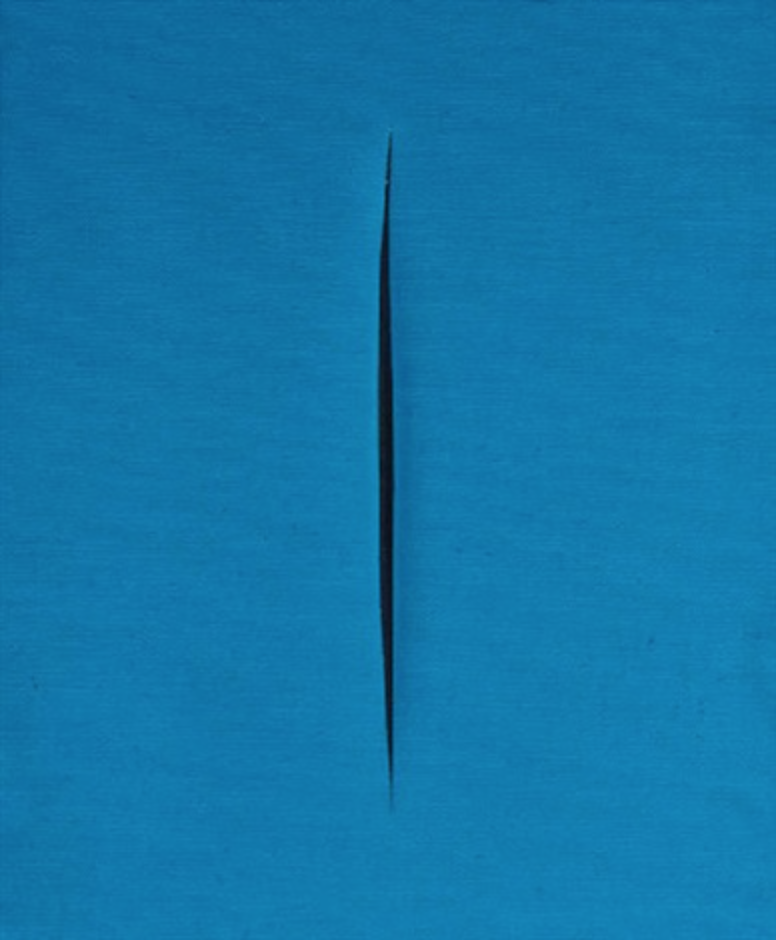

Comparing this to spatial artist Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), who made incisions on canvas in works like "Concetto Spaziale, Attesa" (1965), attempts to break the boundaries between flat painting and the space beyond the frame. This challenges viewers to reconsider the construction, imagination, and reimagining of "painting-sculpture-space." Glajcar's sculptures bring an extension and rhythm of "hollowness" to viewers. Through precise tearing of voids, light enters the cavities, allowing viewers to perceive multiple spaces constructed by light and shadow, opening up imaginations of the fourth dimension. The subversion of paper, the tearing of voids, and the construction imply a kind of destructiveness, leaving marks in real space.

German art historian and director of the Wolfsburg Art Museum, Andreas Beitin, believes that Angela Glajcar's works possess profound contemplation. She presents opposing aspects of human existence: dynamic and static, beauty and destruction, brightness and heaviness, rhythm, and stillness. Due to the inherent nature of paper, fragile yet resilient, it is intriguing to think that the books and sheets we typically peruse can be suspended high in the air, floating freely. The vortex-like voids created by tearing resemble geometric tunnels that extend endlessly, reminiscent of the serrated ridges on glaciers or rock layers and deep caves.

Angela Glajcar's works delve into our lived spaces, environments, and showcase the multifaceted nature of "paper" in terms of light, movement, time, and sound—so robust yet so liberating. Through the subversion and construction of paper, her artworks exceed all imaginable boundaries of reality.

2009-072 Terforation (space), 2009. Paper, structural steelwork.

2019-035 Terforation In-site installation, 2019. 300g torn paper, Bracket made of metal. 500 x 1200 x 250 cm,

Terforation 2015-056, Kunstmuseum Bochum, Germany, 100 x 140 x 500 cm, Paper 400g, torn, metal mounting and plastic

Arsis 2015-054, Gutenberg Museum, Germany, Size depends on site, paper 350g, torn, screwed, metal mounting

Terforation 2012-014, Museum Washingtonn, U.S.A., 140 x 100 x 500 cm, Paper 350g, torn, metal mounting and plastic

Montcanus 2011-072, Church Allerheiligen, Germany , 650 x 156 x 1500 cm, glass fabric, 170g, cut, metal

Solo Exhibitions

2022 Torn space ,Bluerider Art Shanghai (CHN)

2022 Scale Matters,Karin Weber Gallery Hong Kong (CHN)

2021 Angela Glajcar : “Papier fâché” ,Stream Art Gallery, Brussels (BE)

2021 Scale Matters 2021-006, Site specific installations, private collection, Wien (AUT)

2020 my silence is my self defense, K.Oss Gallery, Detroit (USA)

2020 Terforation, Bluerider Gallery, Taipeh (TWN)

2020 we are talking about the space between us, Galerie Martin Kudlek, Köln (DE)

2019 Terforation, Galerie Philippe David, Zürich (CH)

2019 blanco y nero, Galerie Marita Segovia, Madrid (ES)

2019 snowblind, Galerie Nanna Preußners, Hamburg (DE)

2019 torn space, Galerie Utermann, Dortmund (DE)

2018 carte blanche, Les 3 Cha centre d‘art, Châteaugiron (Fr)

2018 Plateau München, Heitsch Gallery, München (DE)

2018 Luce e Spazio, MEB Arte Studio, Borgomanero (IT)

2017 Terforation 2.0, Museum Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden (DE)

2017 Layers, Heitsch Gallery, München (DE)

2017 Synthesis, Bromer Kunst, Roggwil (CH)

2016 sensazioni di carta, Galerie Antonella Cattani Contemporary, Bolzano (IT)

2016 terra incognita, Kunstverein Coburg und St. Augustin, Coburg (DE)

2015 Papier ist für die Ewigkeit, Gutenberg-Museum, Mainz (DE)

2015 Weiß ist das neue Schwarz, Heitsch Gallery, München (DE)

2015 white glass, Diana Lowenstein Gallery, Miami (USA)

2015 Terforation, MOCA Jacksonville, Jacksonville (USA)

2015 white, Andipa Gallery, Londen (UK)

2015 Terforation, Galerie Nanna Preußners, Hamburg (DE)

2015 within the light, Southwark Cathedral, London (UK)

2014 white glass, Galerie Kudlek, Köln (DE)

2014 Angela Glajcar Escultura, Espacio Micus Arte Contemporáneo, Ibiza (ES)

2014 summer, Hollis Taggart, New York (USA)

2014 weiss, Kunsthalle zu Kiel, Kiel (DE)

2013 Galerie Nusser & Baumgart, München (DE)

2013 Terforation, Andipa Gallery, London (UK)

2013 Galerie Löhrl, Mönchengladbach (DE)

2013 Galerie Antonella Cattani contemporary art, Bolzano (IT)

2012 pure paper, Kunstverein Münsterland, Coesfeld (DE)

2012 paper and light, Diana Lowenstein Gallery, Miami (USA)

2011 Metall Papier Komplementär, Emsdettener Kunstverein, Emsdetten (DE)

2011 the light within, KunstKulturKirche Allerheiligen, Frankfurt a.M. (DE)

2011 Terforation (rising), KN Studio, Verona (IT)

2011 Curalium, College of the Holy Cross, Worcester (USA)

2010 Carta Spaziale, Grossetti Arte Contemporanea, Milano (IT)

2010 Ad Id Temporis, Sint-Anna-ten-Drieënkerk, Antwerpen (BE)

2009 innen–raum–außen, Galerie Löhrl, Mönchengladbach (DE)

2009 Carta Spaziale, Associazione Margherita Ripamonti, Como (IT)

2009 Ad Tempus, Johanniskirche, Hanau (DE)

2009 Ad Lucem, Kunst-Station Sankt Peter, Köln (DE)

2009 Ge-rissen, Österreichisches Papiermachermuseum, Steyrermühl (AT)

2009 Papierwelten, Kunstverein Hof, Hof (DE)

2009 Arsis, KunstRaum Hüll, Drochtersen-Hüll (DE)

2009 Angela Glajcar Skulpturen, C. Wichtendahl Galerie, Berlin (DE)

2009 Papierwelten, Kunstverein Ludwigshafen, Ludwigshafen (DE)

2009 Monolog | Dialog, Essenheimer Kunstverein, Ingelheim (DE)

2008 secret, Galerie Maurer, Frankfurt a.M. (DE)

2008 Sculptures Célestes, Abbaye d‘Alspach, Kaysersberg (FR)

2008 Angela Glajcar Papier – Dieter Kränzlein Stein, Galerie Roland Aphold, Allschwil-Basel (CH)

2008 Angela Glajcar & Nele Waldert – Skulpturen und Objekte, Galerie Peters-Barenbrock, Ahrenshoop (DE)

2008 Dialogue Poétique, Kunst Forum D‘Art, Vaudrémont (FR)

2008 inside – outside, Kunstverein Siegen, Siegen (DE)

2008 Papier | Schatten – Kunst im Lichthof, Stora Enso Maxau GmbH, Wörth (DE)

2008 Papier lesen, Landesbibliothek, Speyer (DE)

2007 Tänze im Raum – Papierskulpturen und Kunststoffinstallationen, Südwestrundfunk, Mainz (DE)

2007 Angela Glajcar | Lichtblick, Kunstverein Heidenheim, Heidenheim (DE) leichte – schwere. 2007 Angela Glajcar Papierskulpturen, Galerie Maurer, Frankfurt

a.M. (DE)

2007 Angela Glajcar, Galerie von Waldenburg, Waldenburg (DE)

2006 Angela Glajcar Skulpturale Papierobjekte und Installationen, Galerie B. Haasner, Wiesbaden (DE)

2006 Angela Glajcar Terforation, C. Wichtendahl Galerie, Berlin (DE)

2006 Contrarius – Lichtschatten, Schloss Charlottenburg Berlin, Berlin (DE), P 15

2006 Angela Glajcar Papierskulpturen, Up Art Galerie, Neustadt-Haardt (DE)

2006 Terforation, Nassauische Sparkasse, Wiesbaden (DE)

2006 Angela Glajcar Papierarbeiten, Kunstverein Trier Junge Kunst, Trier (DE)

2005 Angela Glajcar Contrarius, C. Wichtendahl Galerie, Berlin (DE)

2005 Angela Glajcar Contrarius, Theater Kleines Haus, Mainz (DE)

2005 Stadtkünstlerin Spaichingen 2005, Forschner-Gebäude, Spaichingen (DE)

2005 Angela Glajcar Papierinstallationen, Galerie Kunsthalle Koblenz, Koblenz (DE)

2004 Glajcar | Landau Malerei und Skulptur, Landtag RLP, Mainz (DE)

2004 Angela Glajcar Contrarius, Kunstverein Friedberg, Friedberg (DE)

2003 Angela Glajcar Skulpturen und Wandobjekte, Galerie B. Haasner, Wiesbaden (DE)

2002 Korrespondenz im Raum, Kunstverein Speyer, Speyer (DE)

2002 Angela Glajcar Zonta Kunstpreis 2002, Kulturschmiede, Nieder-Olm (DE)

2001 Angela Glajcar Skulpturen, Schloss Waldthausen, Mainz (DE)

2000 Angela Glajcar Skulpturen in Holz und Stahl, Galerie Haus Eichenmüller, Lemgo (DE)

2000 Noyane Holzskulpturen 1999/2000 Angela Glajcar, Haus Metternich, Koblenz (DE), P 2

2000 Angela Glajcar Skulpturen in Holz und Stahl, Galerie Eva Tent, Koblenz (DE)

2000 Skulpturenausstellung mit Werken von Angela Glajcar, Wernerkapelle, Bacharach (DE)

Group Exhibitions

2023 Homeland Universe, Bluerider ART, London (UK)

2022 Cut, Torn and Folded,Galerie Martin Kudlek Köln (DE)

2022 The Abstract Landscape,Galerie Kellermann Düsseldorf (DE)

2022 Arte sobre papel,Galeria Marita Segovia, Madrid (ES

2022 Art Düsseldorf 2022,Galerie Löhrl (DE) // Galerie Utermann (DE)

2022 Miniartextil, Arte & Arte,M4 Mairie de Montrouge (FR)

2022 International Paper Biennale, Changchun (CHN)

2021 Lunar Sonata,Hanji Works and Contemporary Art,Jeonbuk Museum of Art South Korea (KOR)

2021 Papier im Raum – Spatial Paper, Haus des Papiers, Berlin (DE)

2021 Vier Elemente,Galerie Löhrl, Mönchengladbach (DE)

2021 The Sensible Practice, Galeria Antonella Cattani Contemporary Art, Bozen (IT)

2021 ARTE SOBRE PAPEL,Galeria Marita Segovia, Madrid (ES)

2020 paper routes – women to watch 2020, NMWA National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington (USA)

2020 Künstlerinnen in der Bochumer Kunstsammlung, Kunstmuseum Bochum (DE)

2020 Geheimnis Papier, Museum Schloss Burgau, Düren (DE)

2019 one if by land, Powerlong Museum, Shanghai (CHN)

2019 Cheongju Craft Biennale 2019, Cheongju (KOR)

2019 Prospect, Sharjah Art Museum, Sharjah (U.A.E.)

2018 weiss, Galerie Sebastian Fath, Mannheim (DE)

2017 CODA Paper Art, CODA Museum, Apeldoorn (NL)

2017 in the absense of color, Hollis Taggart Galleries, New York (USA)

2017 Bild | Skulptur, Galerie Bechter Kastowsky, Wien (AUT)

2017 dark, liquid. , Kunstverein Tiergarten in der Galerie Nord, Berlin (DE)

2016 schwarz weiss, Galerie Löhrl, Mönchengladbach (DE)

2016 new masters vs modern masters, Heitsch Gallery, München (DE)

2016 shifting surfaces, Karin Weber Gallery, Hong Kong (CHN)

2015 a touch of glass, Karin Weber Gallery, Hong Kong (CHN)

2015 konkret mehr Raum!, Kunsthalle Osnabrück, Osnabrück (DE)

2014 white sensation, Galerie Nanna Preußners, Hamburg (DE)

2014 25th anniversary show, Diana Lowenstein Gallery, Miami (USA)

2014 se dico aria, caleidoscopio, Festival della Arti, Camerano (IT)

2014 impressoni astratte, Museion Bozen, Bolzano (IT)

2013 On the Edge, Cheryl Hazan Gallery, New York (USA)

2013 Zwischen Himmel und Erde, Galerie Martin Kudlek, Köln (DE)

2013 In Between, Museum Kasteel van Gaasbeek, Lennik (BE))

2012 Andipa Gallery, London (UK) Papiergewisper, Galerie Spielvogel, München (DE)

2012 Arbeiten aus Papier, Galerie Splettstößer, Kaarst (DE)

2012 just paper, Kunstverein Marburg, Marburg (DE)

2012 Papierarbeiten 3, Galerie Maurer, Frankfurt a.M. (DE)

2012 oltre l‘attimo, Grossetti Arte Contemporanea, Milano (IT)

2012 Künstlerfreunde, Kunstverein Speyer, Speyer (DE)

2011 terra incognita. Weltbilder – Welterfahrungen, ALTANA Galerie, Dresden (DE)

2011 Papier=Kunst 7, Neuer Kunstverein Aschaffenburg, Aschaffenburg (DE)

2011 my collection 1916 | 2011, Grossetti Arte Contemporanea, Milano (IT)

2011 Schönheit und Natur, Wasserstandsturm, Bingen (DE)

2011 Vivere e pensare in carta e cartone: tra arte e Design, Museo Diocesano Milano, Milano (IT)

2011 30 Jahre Galerie Löhrl in Mönchengladbach, Galerie Löhrl, Mönchengladbach (DE)

2010 Sammlung Dellwing Speyer, Städtische Galerie, Speyer (DE), P 31

2010 white meditation room, Grossetti Arte Contemporanea, Milano (IT)

2010 Papierarbeiten 2, Galerie Maurer, Frankfurt a.M. (DE)

2010 miniartextil, San Francesco, Como (IT)

2010 Regionale 2010, Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen (DE)

2010 sans papier – sons papier, Politecnico di Milano, Milano (IT)

2010 paperworks, C. Wichtendahl Galerie, Berlin (DE)

2009 Collagen. Sammeln, Kunstverein Augsburg, Augsburg (DE)

2009 Papierarbeiten, Galerie Maurer, Frankfurt a.M. (DE)

2009 all about light, C. Wichtendahl Galerie, Berlin (DE)

2009 Qui é altrove, Fondazione Malvina Menegaz, Castelbasso (IT)

2009 Papierobjekte, Haus der Modernen Kunst, Staufen-Grunern (DE)

2009 focus, Grossetti Arte Contemporanea, Milano (IT)

2008 Papierkunstjahr, Buchladen im Roten Haus, Titisee-Neustadt (DE)

2008 Open Air 19. Skulpturenausstellung der Darmstädter Sezession, Ziegelhütte, Darmstadt (DE) 2008 Exposición Colectiva, Galeria Marita Segovia, Madrid (ES)

2008 Holland Papier Biennale 2008, Museum Rijswijk und CODA Apeldoorn, Rijswijk und Apeldoorn (NL)

2008 Papier und Raum, Galerie Thomas, München (DE)

2007 Geometrisk Abstraktion XXVI, Konstruktiv Tendens, Stockholm (SE)

2007 Kunst im Schloss, Schloss Wertingen, Wertingen (DE)

2007 Schnitt | Riss, C. Wichtendahl Galerie, Berlin (DE) plus.

2007 Stipendiatinnen und Stipendiaten der Stiftung Vordemberge-Gildewart 1994–2007, Museum Wiesbaden und Nassauischer Kunstverein, Wiesbaden (DE)

2007 Faszination Papier, Kunstverein Nördlingen, Nördlingen (DE)

2007 schwebend hovering, Galerie Dorothea van der Koelen, Mainz (DE)

2006 Papierarbeiten – Paperworks, C. Wichtendahl Galerie, Berlin (DE)

2006 Raumtäuschungen, Kahnweilerhaus, Rockenhausen (DE)

2005 Papier, Künstlerverein Walkmühle, Wiesbaden (DE)

2005 20 Jahre Galerie B. Haasner, Wiesbaden (DE)

2005 60 Jahre Pfälzische Sezession, Städtische Galerie Speyer und Landesvertretung Rheinland-Pfalz, Speyer, Berlin (DE)

2005 Papier=Kunst 5, Neuer Kunstverein Aschaffenburg, Aschaffenburg (DE)

2005 Junge Rheinland-Pfälzer Künstlerinnen und Künstler – Emy-Roeder-Preis 2005, Kunstverein Ludwigshafen, Ludwigshafen (DE)

2004 Sinn_Flut, Essenheimer Kunstverein, Ingelheim (DE)

2004 Gutsherrinnen, Frauenmuseum Bonn, Bonn (DE)

2003 Junge Rheinland-Pfälzer Künstlerinnen und Künstler – Emy-Roeder-Preis 2003, Wilhelm-

Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen (DE)

2003 Grafik – Malerei – Plastik, Galerie B. Haasner, Wiesbaden (DE)

2003 Förderpreis der Stadt Mainz für Bildende Kunst 2003 – Ausstellung der

2003 Kandidatinnen und Kandidaten, Galerie der Stadt Mainz im Brückenturm, Mainz (DE)

2001 Drei starke Frauen, Kunstverein Bad Dürkheim, Bad Dürkheim (DE)

2001 Form wofür – what for, Pegnitzlofts, Nürnberg (DE)

2000 Gastspiel Darmstädter Sezession, Ziegelhütte, Darmstadt (DE)

2000 Mainzer Skulpturenpark, Volkspark, Mainz (DE)

Awards

1998 Workshop Prize of the Kunststiftung Erich Hauser

1999-2000 Asterstein scholarship of the state of Rhineland-Palatinate

2001-2002 project scholarship “Correspondence in Space”

2001-2002 Bavarian Ministry of Culture

2002 Zonta Art Award Mainz

2004 Vordemberge Gildewart Fellowship

2005 Emy Roeder Prize

2006 Phoenix Art Award

2010 Audience Award of the Regionale in the Wilhelm Hack Museum, Ludwigshafen

2014-2015 city printer Mainz

2021 Paper Art Award 2021, Haus des Papiers Berlin