(Netherland, b. 1953)

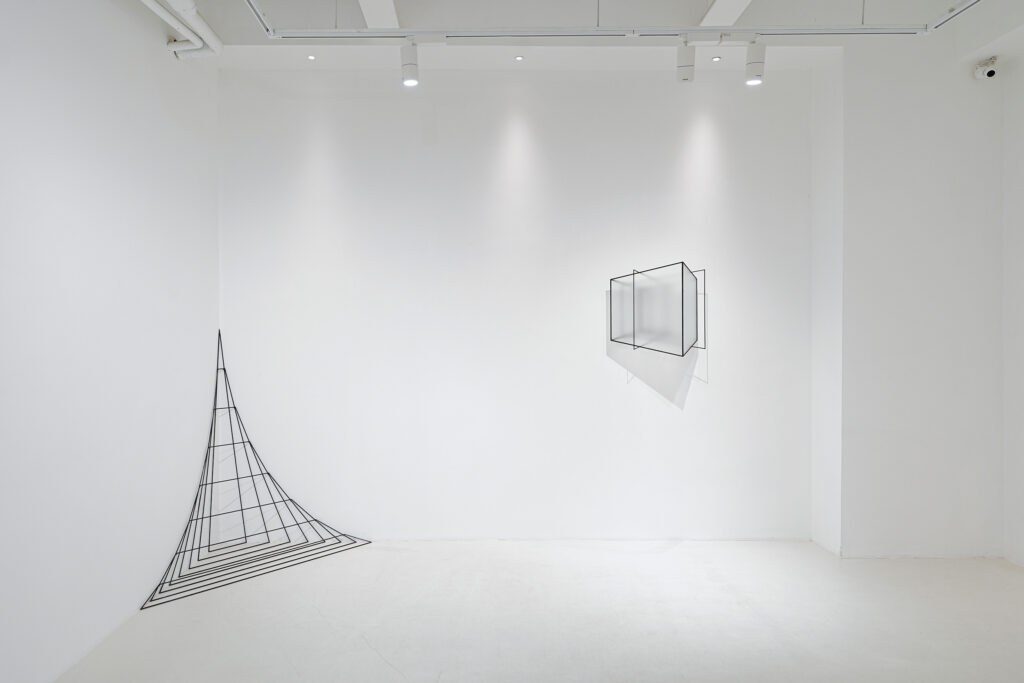

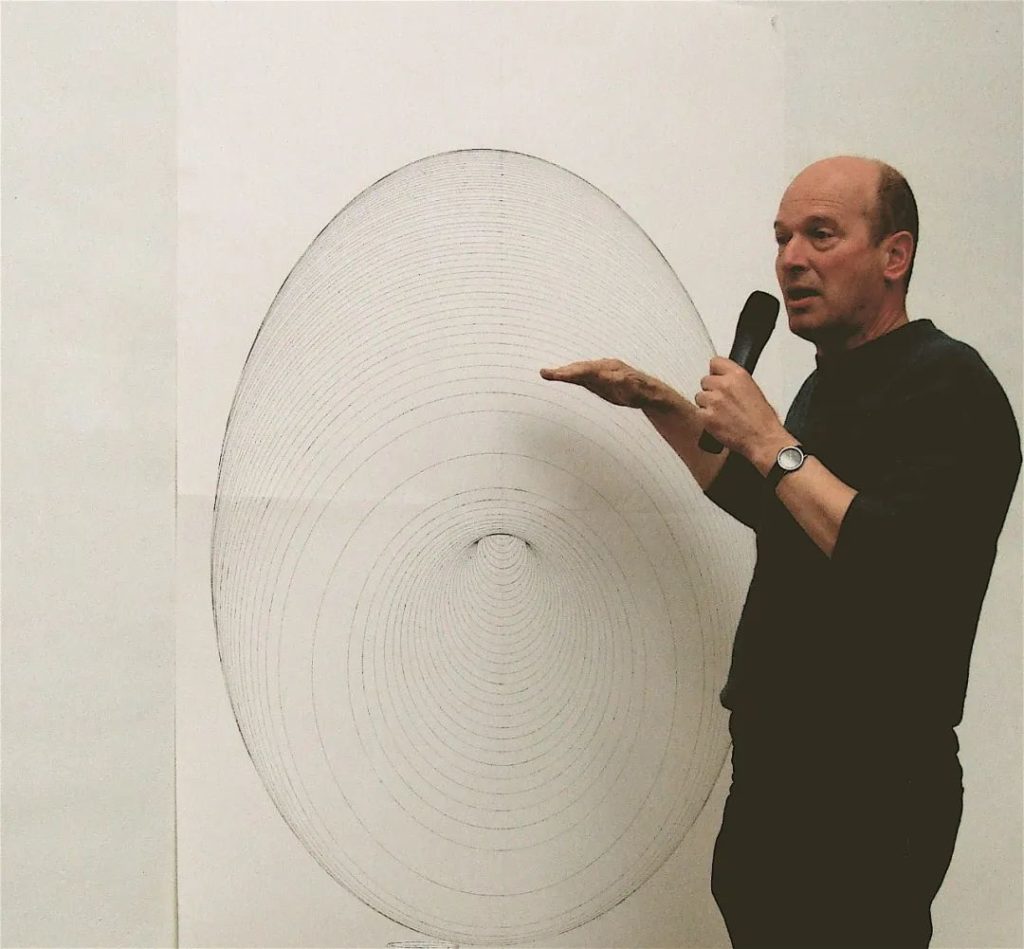

Reinoud Oudshoorn lives and works in Amsterdam. Oudshoorn is known for his minimal sculpture by creating a bridge between the spatial illusion of a flat surface and the concrete reality of a physical object through the language of drawing and sculpture. He has held numerous solo and group exhibitions and his works entered important international collections including Stedelijk Musuem Amsterdam, AkzoNobel Art Foundation, ABN AMRO and Sammlung Schroth.

Participating in the 8th Tallinn Applied Art Triennale "Translucency" at Kai Art Center in Estonia in 2021

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

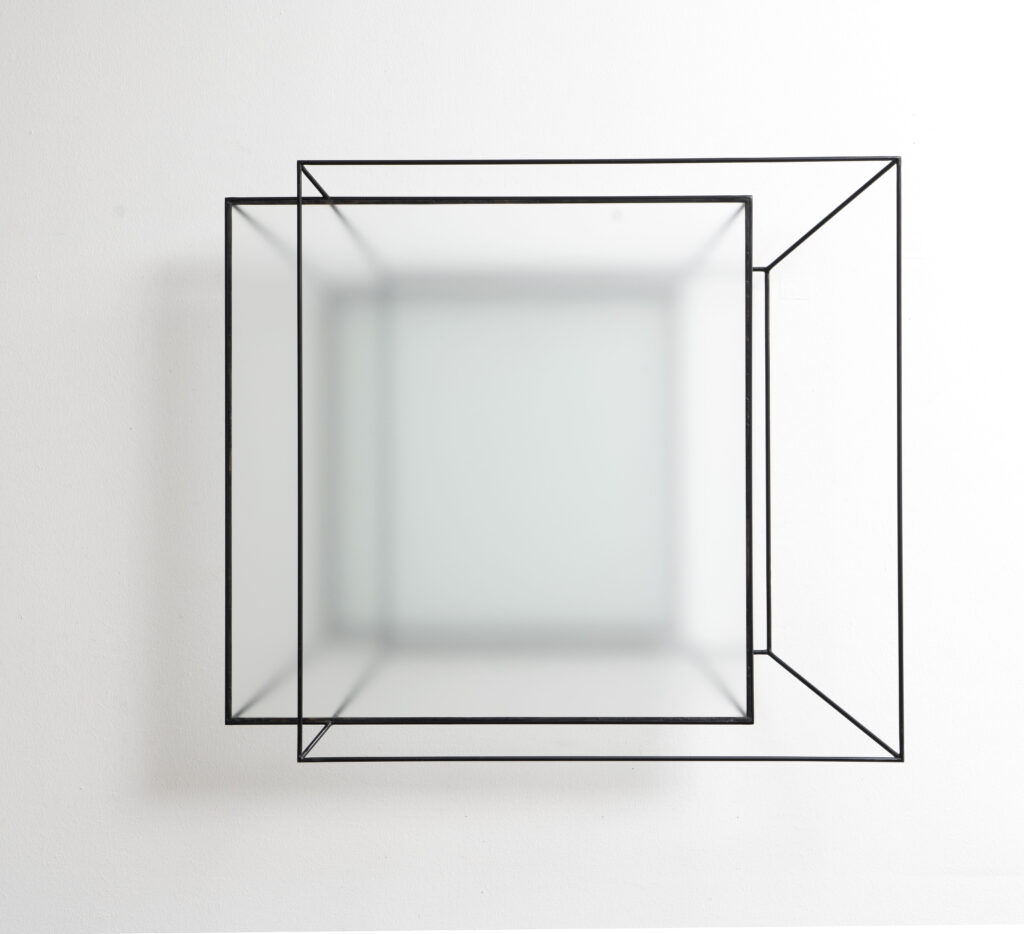

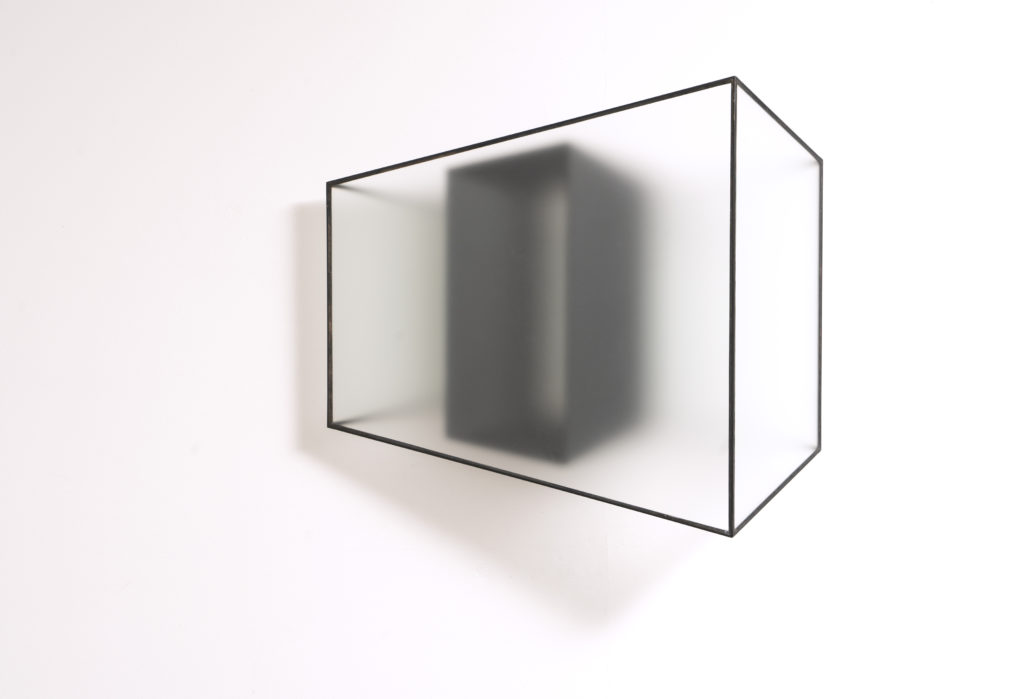

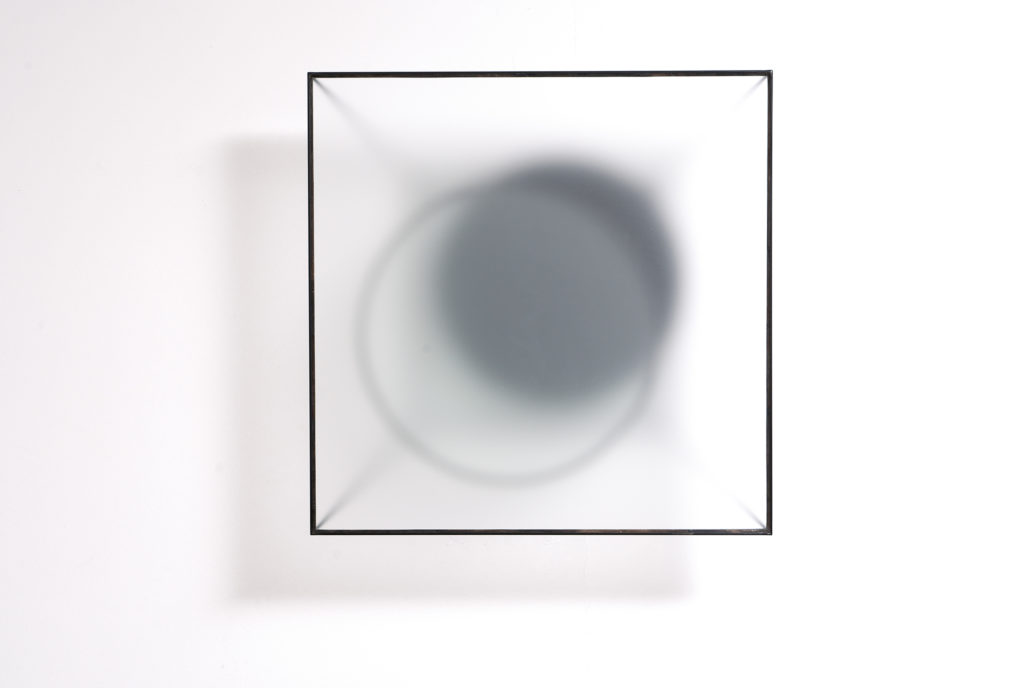

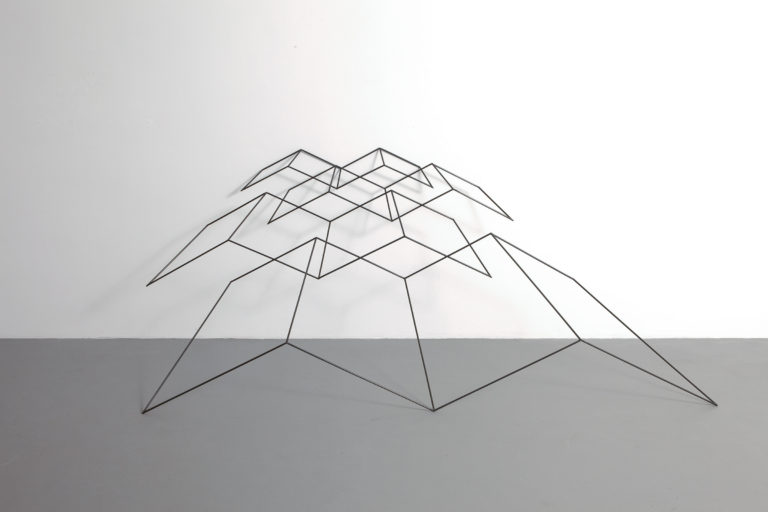

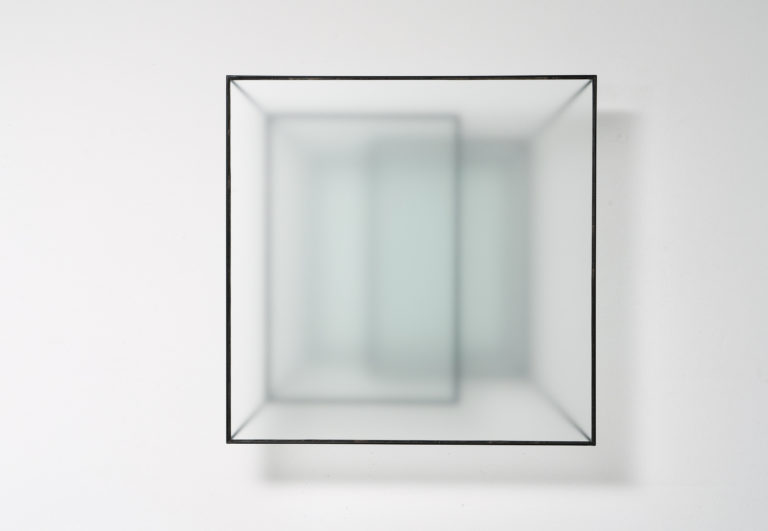

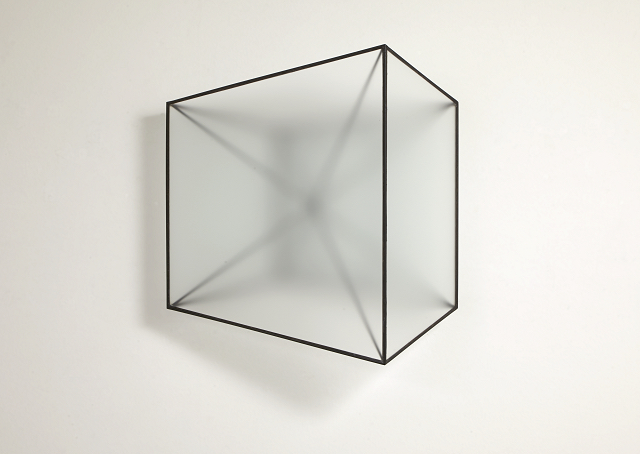

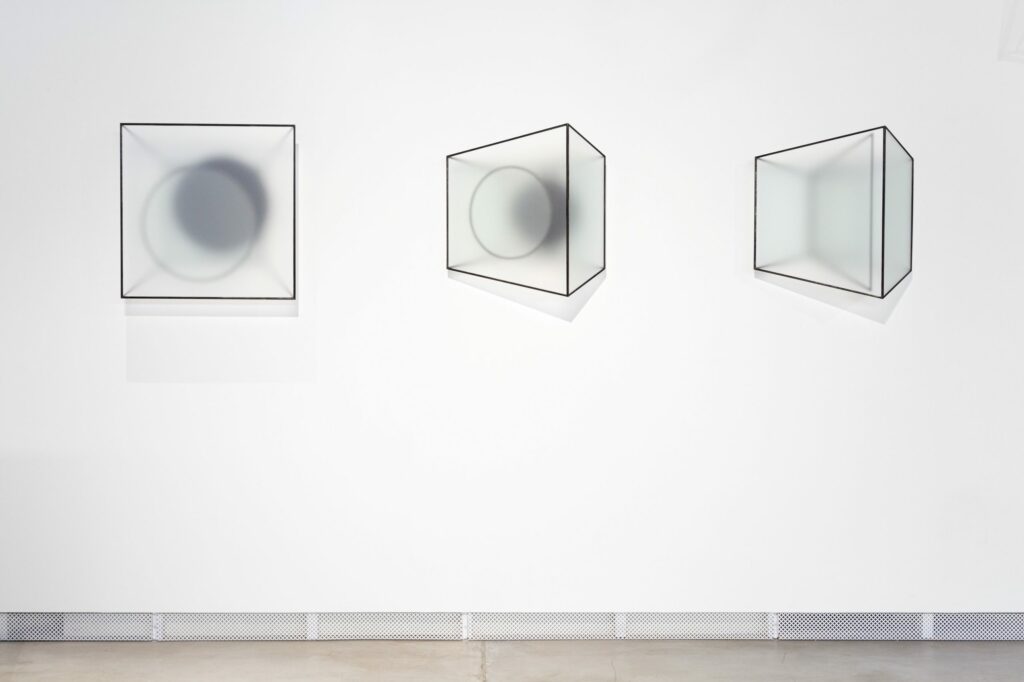

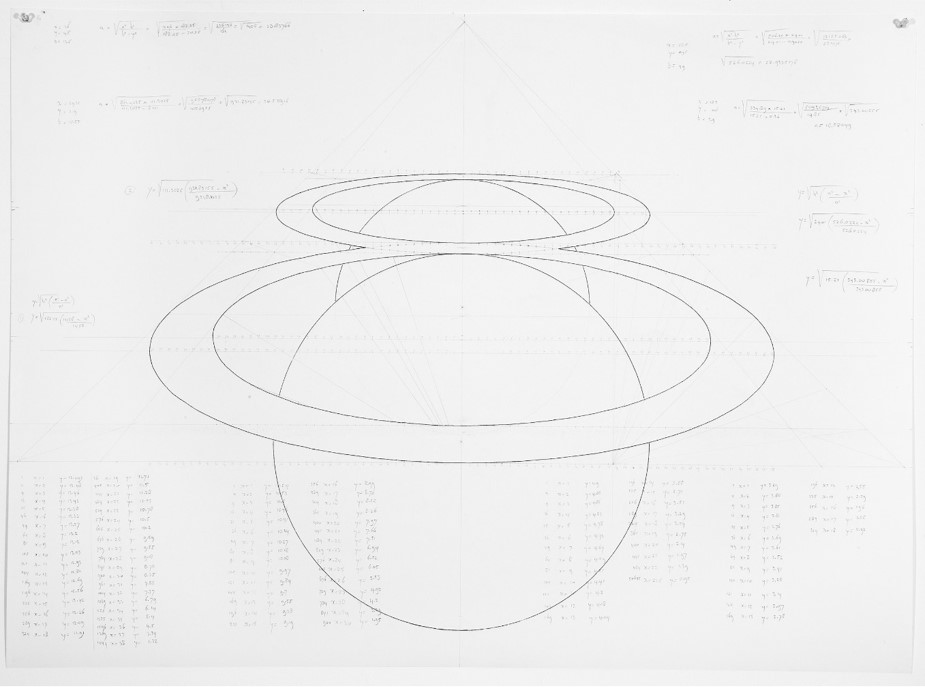

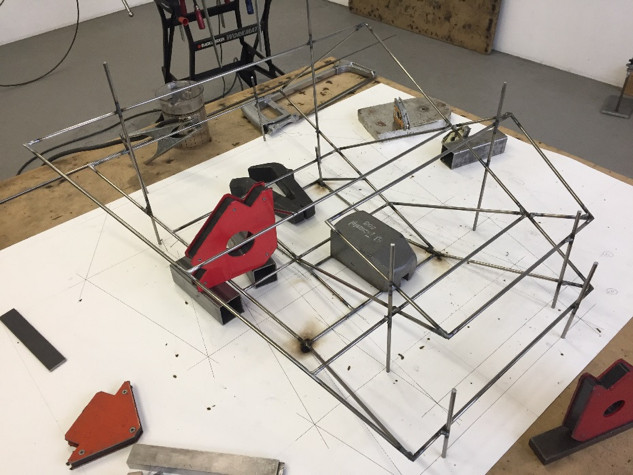

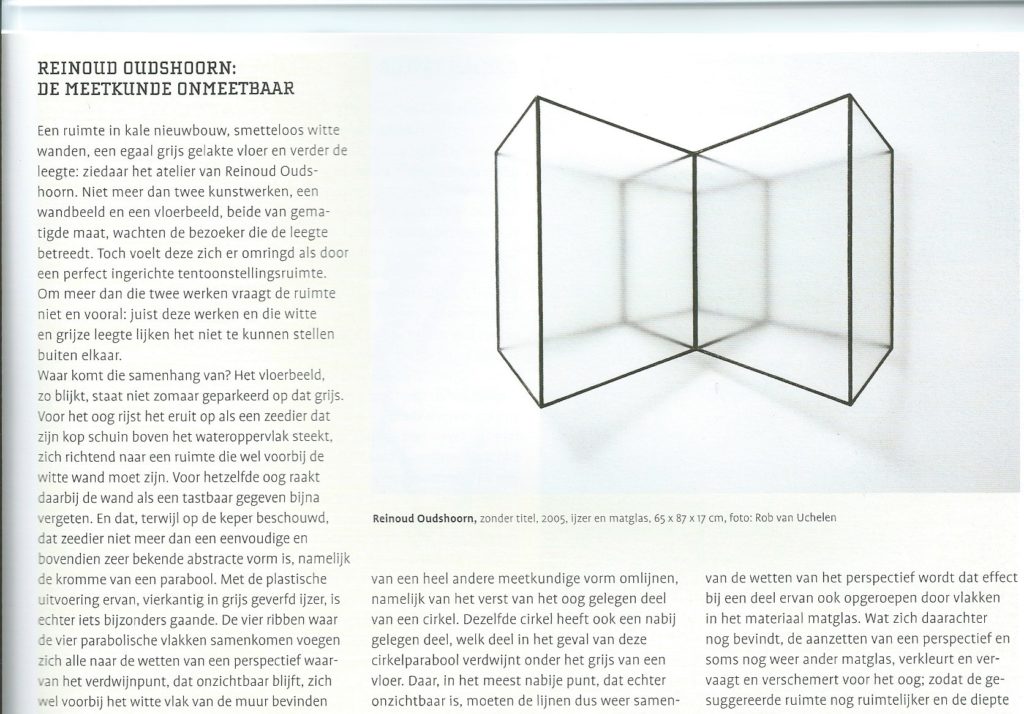

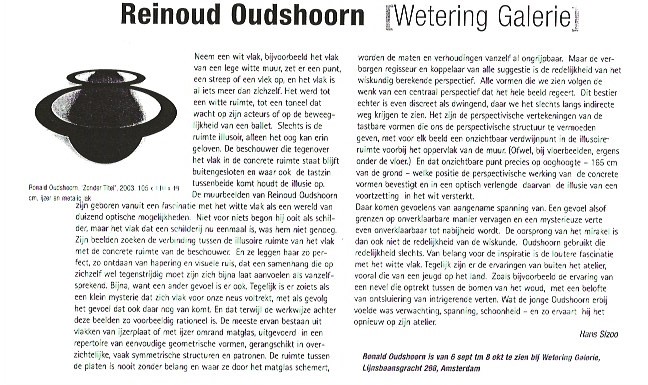

With exact mathematical calculation, Oudshoorn draws the perspective of the shape he would create, transforming the work from lines to planes, then from planes to a space according to the distance and the angles of viewing. Ousdhoorn’s sculptures are often made with iron and frosted glass, the latter a symbol of the contemplative, metaphysical and mysterious, atmospherically reminiscent of the muffled silence of mist, and tying in with the artist’s wish to transport a visual image into a space of one’s own imagination.

Oudshoorn’s inspiration for his sculptures originates from impressions of the world the artist experiences. This can be imagery drawn from nature or architectural shapes, and phenomena like the mist characteristic for his homeland. Abstracted into surfaces and structures, they are transformed into new objects that reveal contemplative and even mysterious qualities. This link between nature and infinity refers to influential artistic movements such as the simplified compositions of the De Stijl with its clear forms or to the atmospheric light of Dutch landscape painting. The play with perception and dissolution of forms relates Oudshoorn’s sculptures to works like the condensation cubes by Hans Haake from the early 60s or Anthony Gormley’s cloud chamber Blind Light.

作品於阿姆斯特丹美術館(Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam )展出

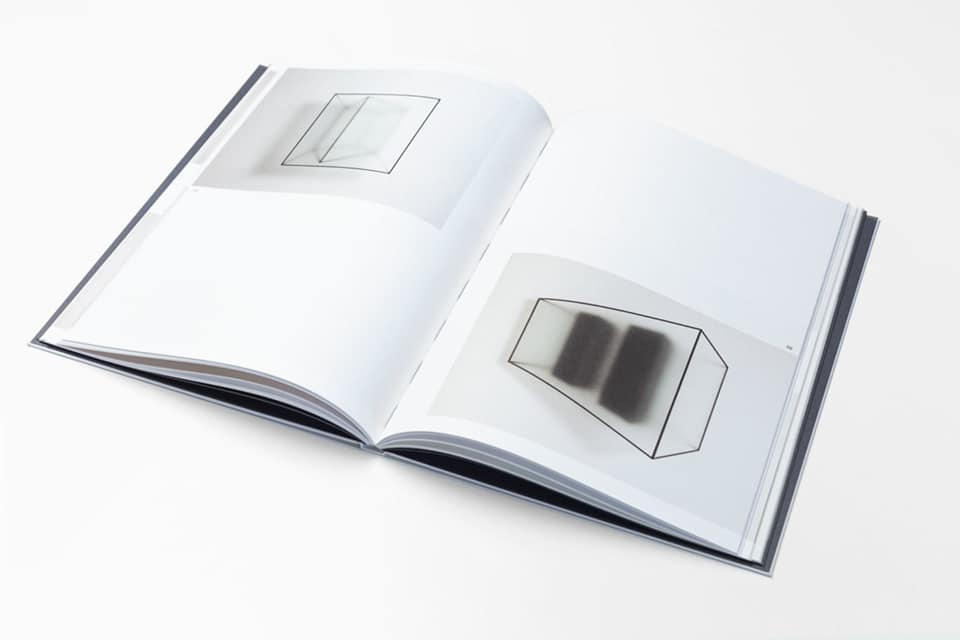

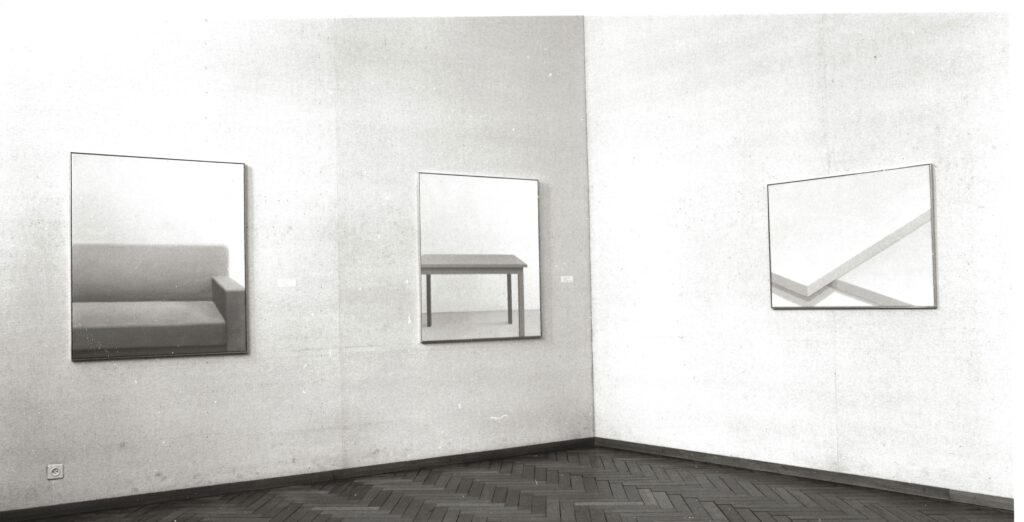

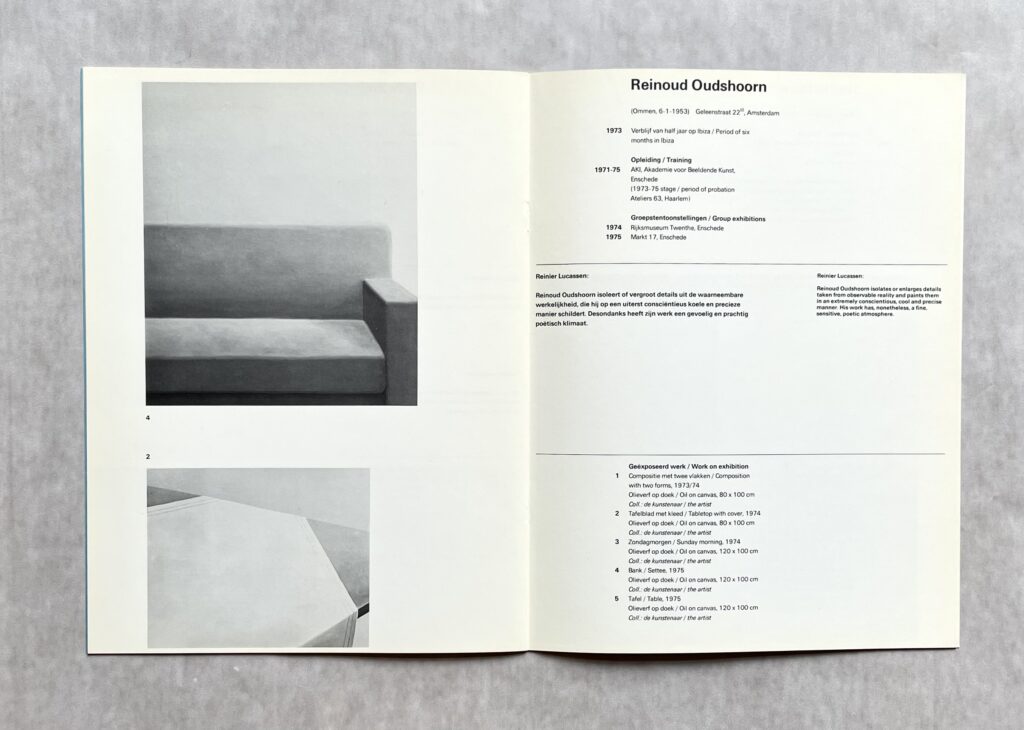

Oudshoorn’s page in the catalogue, the paintings are from 1973 – 1975

an early work from 1990, A-90, lead on wood 180 x 84 x 84 cm

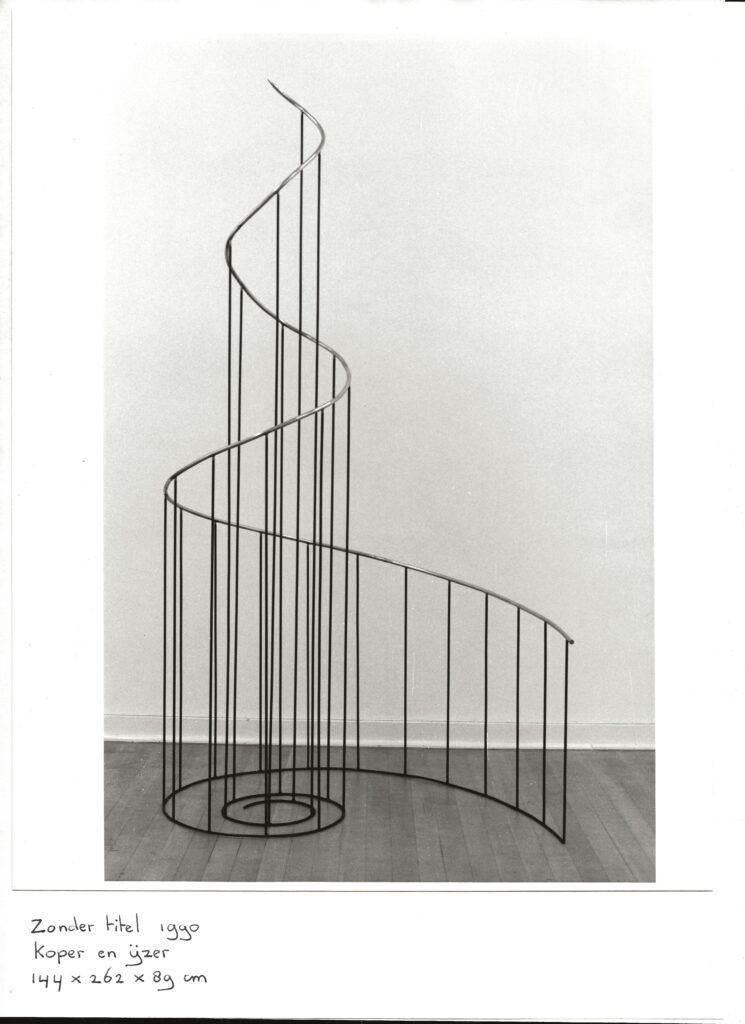

an early work from 1990, copper and steel 144 x 262 x 89 cm.

Reinoud Oudshoorn| G-21|64x64x22cm| Steel and frosted glass

Q-20| 64x70x24cm|Steel and frosted glass

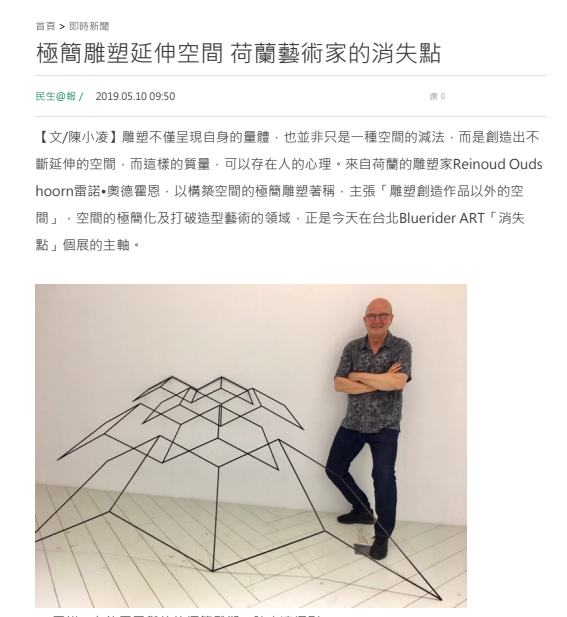

Oudshoorn's first solo show "Vanishing point" at Bluerider ART revolves around the concept of space and spatial illusion that he had been exploring since long. Space that becomes the concrete reality of a three-dimensional, but also spaces that lie in between the shapes and materials visible; areas that cannot be captured or confined and which remain hidden or obscured. "A sculpture must generate more space than it consumes", stated by Oudshoorn. With limited material and surface, the artist seeks to provide viewers the experience of the totality of space through a relatively small object. He explores the gap between finitude of physical subjects and infinity of immaterial subjects, suggesting an endlessness in the space that surrounds us, an infinity of mind and sphere.

Reinoud Oudshoorn's creative manuscript

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2020 Fragmented Truth (with Alice Quaresma), Patrick Heide Contemporary Art, London

2019 Vanishing Point,Bluerider ART, Taipei, Taiwan

2017 Dimensions of three, Allouche Gallery, New York, US

2017 Recent Sculptures, Patrick Heide Art Company, London, UK

2015 Ramakers Gallery, The Hague, The Netherlands

2013 Recent Sculptures, Patrick Heide Art Company, London, UK

2012 Dimensions, Gallery Skape, Seoul, South Korea

2011 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2010 Poetic reality in space, Gallery Skape, Seoul, South Korea

2009 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2008 Art Amsterdam, Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2008 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2005 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2003 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2000 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1998 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1996 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1995 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1994 Path Gallery, Aalst, Belgium

1993 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1992 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1991 Path Gallery, Aalst, Belgium

1990 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1988 Waalkens Gallery, Finsterwolde, The Netherlands

1987 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1985 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1983 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1981 Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1979 Museum Fodor, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1978 Waalkens Gallery, Finsterwolde, The Netherlands

Selected Group Exhibition

2022 The Blue Danube, Bluerider ART ,Shanghai , China

2021 Mental Space,Bluerider ART ,Taipei. , Taiwan

2020 For the Love of Art Part 1and 2, Gallery Ramakers, The Hague

2020 Gallery Ramakers at Art Rotterdam.

2019 Uit het atelier, Gallery Ramakers, The Hague, The Netherlands

2018 3D “Schrift am Bau”, Museum für Gestaltung, Zürich, Switzerland

2018 Volta NY, Allouche Gallery, New York, USA

2017 Machinerie, Proviciehuis, Haarlem, The Netherlands

2017 Art Rotterdam, Ramakers Gallery, The Netherlands

2017 Art Geneva, Patrick Heide, Geneva, Switzerland

2016 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide, Miami, USA

2016 Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day, Ramakers Gallery, The Hague, The

Netherlands

2016 Grand opening new space” Gallery Allouche Gallery, New York, USA

2016 Volta Basel, Patrick Heide, Basel, Switzerland

2016 Konstruction Construction, Museum Sammlung Schroth, Soest, Germany

2016 Art Geneva, Patrick Heide, Geneva, Switzerland

2016 Licht en transparantie, Thomas Elshuis en Reinoud Oudshoorn, Nieuw

Dakota, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2016 Ramakers Gallery, The Hague, The Netherlands

2015 Patrick Heide Gallery on the Miami Pulse, Miami, USA

2015 A call for drawing, Symposium, HKU, Utrecht, The Netherlands

2015 Volta Basel, Patrick Heide Gallery, Basel, Switzerland.

2014 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami, USA

2014 Nanjing International Art Festival, Nanjing, China.

2014 Short-hand-made, Grindel 117, Hamburg. Germany.

2014 20 years anniversary, Ramakers Gallery, The Hague, The Netherlands

2014 Volta Basel, Patrick Heide Gallery, Basel, Switzerland.

2013 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami, USA

2013 Hidden dimension, Gallery Skape, Seoul, South Korea.

2013 The last picture show, Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2013 Hidden dimension, Gallery Skape, Seoul, South Korea

2013 Capriccio, JCA de KOK centre for contemporary art, The Hauge, The

Netherlands

2013 Reinoud Oudshoorn and Jérôme Touron, Ramakers Gallery, The Hauge, The

Netherlands

2012 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami, USA

2012 Gallery Skape, Gallery Seoul Art Fair, Seoul, South Korea

2011 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami, USA

2011 Permanent Exibition, Skape Gallery, Seoul, South Korea

2010 PULSE Miami, Patrick Heide Gallery, Miami USA

2010 Space A 2010, Gallery Space, Seoul, South Korea

2008 Ten Feet De Vishal, Haarlem, The Netherlands

2007 De keuze van Lucassen Ramakers Gallery, The Hague

2006 Façade Arti et Amicitiae, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2001 A Public Space 2001 Odyssey Arti et Amicitiae, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1997 Nooit zag ik Awater zo nabij Oude Kerkje, Kortenhoef, The Netherlands

1997 One Line Drawing, Ubu Gallery, New York, USA

1996 The Dutch Connection Marshall Art Gallery, Memphis TN, USA

1996 Weatherview Norwich Gallery, Norwich, UK

1994 The Collection Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1994 De keuze van Betty van Garrel Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The

Netherlands

1993 Atelier Mémoire, Paris, France

1993 20 Years Wetering Gallery Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1993 Kai,Sagaert et Oudshoorn Atelier Mémoire, Paris, France

1992 Le Génie de la Bastille Paris, France

1992 Gemeente Kunstaankopen 1991 Museum Fodor, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1990 Liberations Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1989 Kunstlijn Sculpture Route Zwolle-Emmen, The Netherlands

1989 AMRO Bank Collection, A Choice Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The

Netherlands

1988 Spiel der Uberraschungen der Europaïschen Kunst des 20 Jahrhundert,

Bochholt, Germany

1986 KunstRai, Wetering Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1984 De Kampanje, Den Helder, The Netherlands

1981 Felison op Beeckestijn, with Marlene Dumas, Velzen Zuid, The Netherlands

1979 Van Krimpen Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1976 11 Painters, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

1975 Markt 17, Enschede, The Netherlands

1974 Rijksmuseum Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands

Collections

Akzo Nobel Art Foundation

Collection Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

ABN AMRO Art Collection

The Chadha Art Collection

Eleanore De Sole Collection

Joods historisch museum

University Medical Center Utrecht

Collection Sammlung Schroth, Germany

Selected Publications

2019 “Reinoud Oudshoorn” Book, monograph.

2018 Patrick Heide Contemparary Art “Ten Years”

2017 Collection “Sammlung Schroth (1981-2016)”, Stiftung Konzeptuelle Kunst.

2017 Safari Typo Amsterdam, by Bas Jacobs

2013 Den Haag Centraal, Culture, 12-04-2013 “Vernuftig spel met ruimte en kleur”

door Egbert van Faassen.

2012 Cat. Gallery Skape, Reinoud Oudshoorn,”Dimensions” by Wonseok Koh

[Curator Arko Art Center]

2012 ART in culture, Seoul, Korea “Reinoud Oudshoorn / Choi KI Seog”

by Gim Jonggil

2012 Sunday Magazine, Seoul Korea Gallery review, Reinoud Oudshoorn at

Gallery Skape.

2011 Space, Architecture and Art magazine, Nr 529. “Poetics of space” by

Yunkyong Kim

2010 Cat. Gallery Skape “Reinoud Oudshoorn, Poetic reality in space”

2009 Kunstbeeld “Reinoud Oudshoorn, Anna van Leeuwen [Wetering Galerie]”

2008 “Reinoud Oudshoorn” Book, monograph.

2008 Kunstbeeld “Wiskunde voor de verbeelding”, Hans Sizoo

2006 NRC Handelsblad “Tijdreis door het gebouw van Arti”, Machteld Leij

2003 Kunstbeeld “Reinoud Oudshoorn, Wetering Galerie”, Hans Sizoo

2003 Items “Harde cijfers”, MVE

2001 Cat. Amsterdams Fonds voor de Kunst “A Public Space 2001, Odyssey”,

Amsterdam

2000 Kunstbeeld “Reinoud Oudshoorn, Wetering Galerie”, Willem van Beek

2000 Het Nederlandse Kunstboek Richard Fernhout/ Colin Huizing, Waanders

Publishers b.v. Zwolle, NL

1998 NRC Handelsblad “Wetering Galerie” Janneke Wesseling

1997 Stichting Collage Kortenhoef “Nooit zag ik Awater zo van nabij”

1997 The New York Times, Art in Review “One-Line Drawing”, Roberta Smith

1996 Het Financieele Dagblad “Expositie zonder titel toont levende joodse cultuur”,

Marty Bax

1996 The Memphis Flyer, “Dutch Treat”, Nancy Muse, Memphis TN, USA

1996 Cat. Norwich Gallery “Weatherview”, Norwich, UK

1995 Het Parool “Moderne Kunst in joodse context”, Pietje Tegenbosch

1994 Cat. Info Mémoart “Spécial Trones des Artistes”, édité par Atelier Mémoire,

Paris

1992 Het Parool “Abstractie”, Jan Bart Klaster

1992 Cat. Quartier de la Bastille, ‘Le Genié de la Bastille’, Paris

1992 Cat. Gemeente Kunstaankopen 1991 “Amsterdam Koopt Kunst”, Museum

Fodor, Amsterdam

1990 Het Parool “Afgebakende ruimte voor herinneringen”, interview by Jan Bart

Klaster

1990 Cat. Joods Historisch Museum “Bevrijdingen”, Amsterdam

1989 Het Parool, kunstbijlage “De Prent van Reinoud Oudshoorn”

1989 Cat. Stichting Beeldenroute Overijssel “Kunstlijn”, beeldenroute

Zwolle-Emmen

1989 Cat. Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam “De AMRO Bank collectie, een keuze”

1988 Cat. Tentoonstellingsdienst Overijssel “Spel der Verrassingen, Europese Kunst

van de 20ste eeuw”

1985 Het Financieele Dagblad “Beeldtekens”, Walter Barten

1984 Cat. De Kampanje, Den Helder NL

1983 Het Parool “Lichtvoetige Kunstwerken”, Frans Duister

1981 Haarlems Dagblad “Oudshoorn en Dumas dwingen tot kijken”, Kunstredactie

1981 NRC Handelsblad, “Dumas/ Oudshoorn laten zich inspireren door vreemde

dieren”, Paul Groot

1981 Stichting Felison, “Felison op Beeckestijn”, Velzen-Zuid

1978 Nieuwsblad van het Noorden “Atmosferische verstilling in het werk van

Reinoud Oudshoorn”, Erik Beenker

1976 Het Financieele Dagblad “Tentoonstelling in het Stedelijk”, Mathilde Visser

1976 De Nieuwe Linie, “De inteelt van het Stedelijk Museum”, Jan Juffermans

1976 Cat. Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam “11 Painters”

Tekst Hans Sizoo

Tekst Hans Sizoo

Wide Walls

Wide Walls

Style Master

Style Master