(Germany, b. 1974)

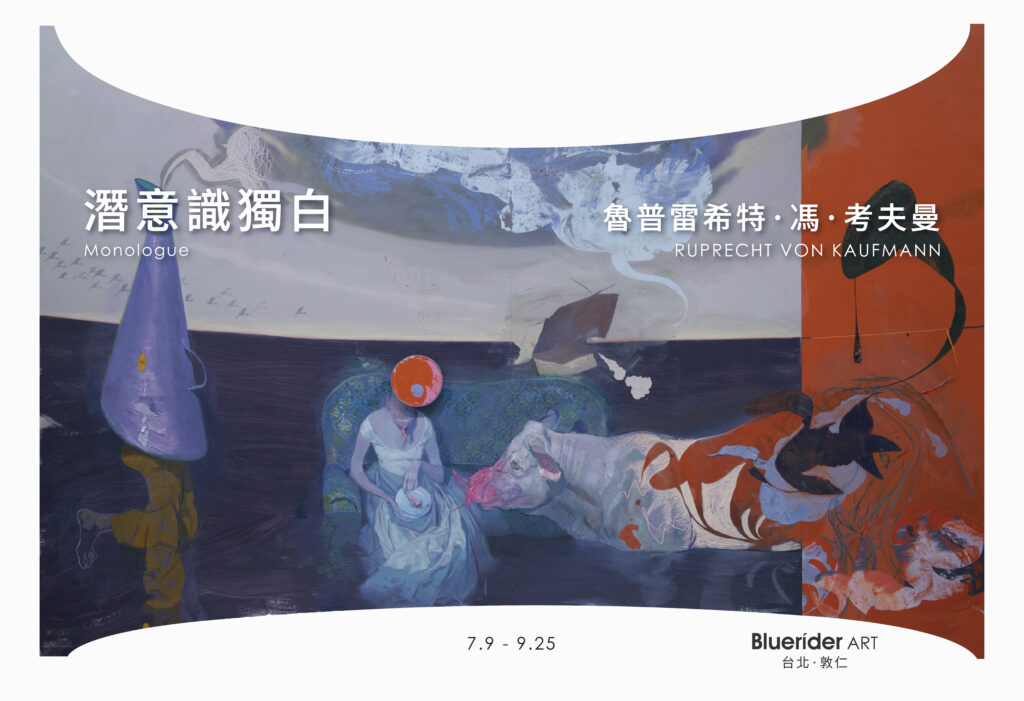

Ruprecht von Kaufmann Born in Munich, Germany, and a graduate of the BFA Los Angeles Art Center College of Design, Kaufmann has been associated with prestigious institutions like Berlin University of the Arts, Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, and Leipzig Academy of Fine Arts. Currently residing and working in Berlin, he is recognized as a prominent visual narrative artist. As an artist focusing on graphic storytelling, Kaufmann explores various facets of human experience through the visual language of contemporary painting. His work showcases critical narratives and parallel realms of reality. Exhibiting in major European cities such as London, Berlin, Stuttgart, Oslo, and New York, his pieces have found a permanent place in renowned collections, including those of the Hort Family in New York, Germany's Sammlung Philara Museum, and the National Bank of Germany in Frankfurt.

2019 Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, Germany

2019 `Inside the Outside´, UN Headquarters, New York

2018 `Die Evakuierung des Himmels´, Kunsthalle Erfurt, Erfurt

2019 “The three princes of serendip” Kunstsammlung Neubrandenburg

2017, Ecce Creatura Groupshow, Kallmann Museum, Ismaning

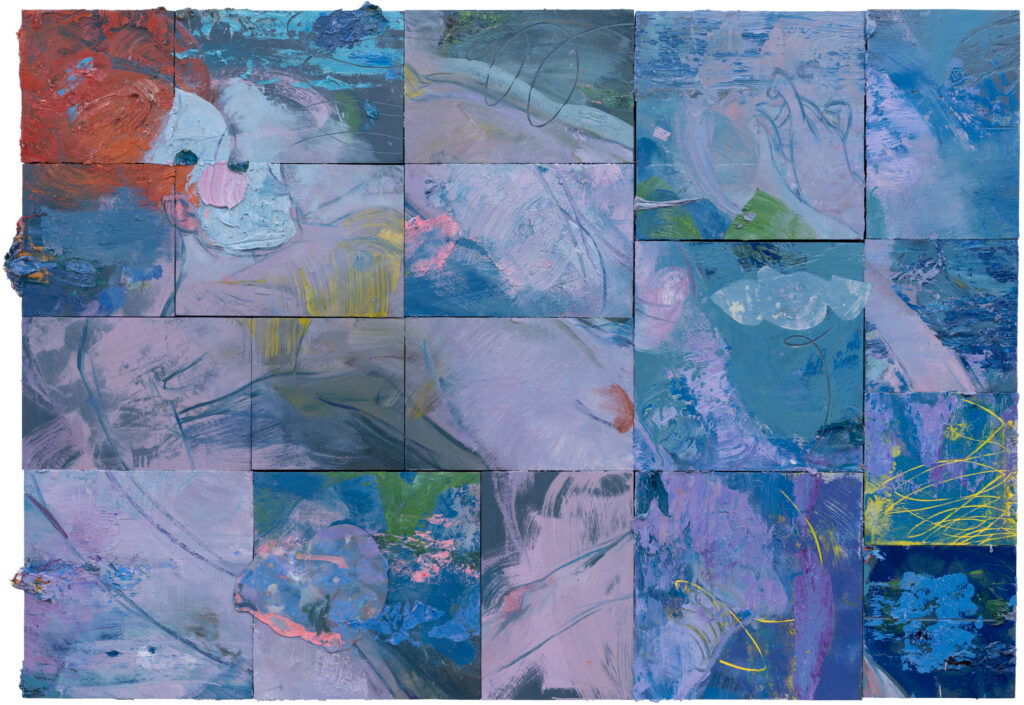

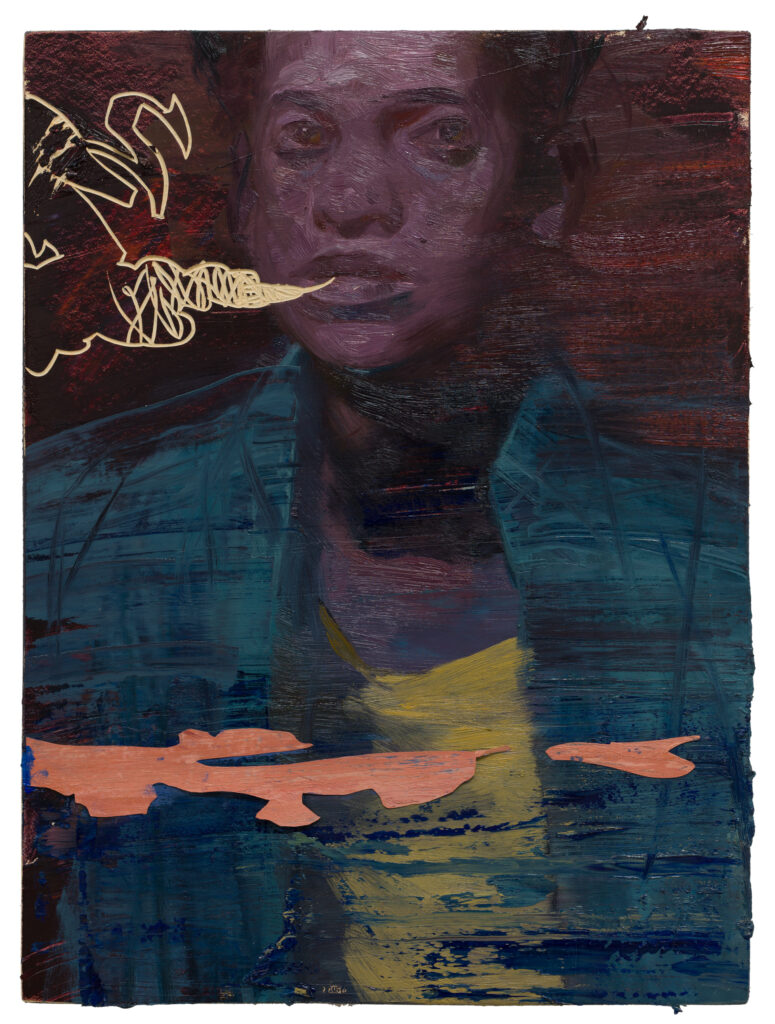

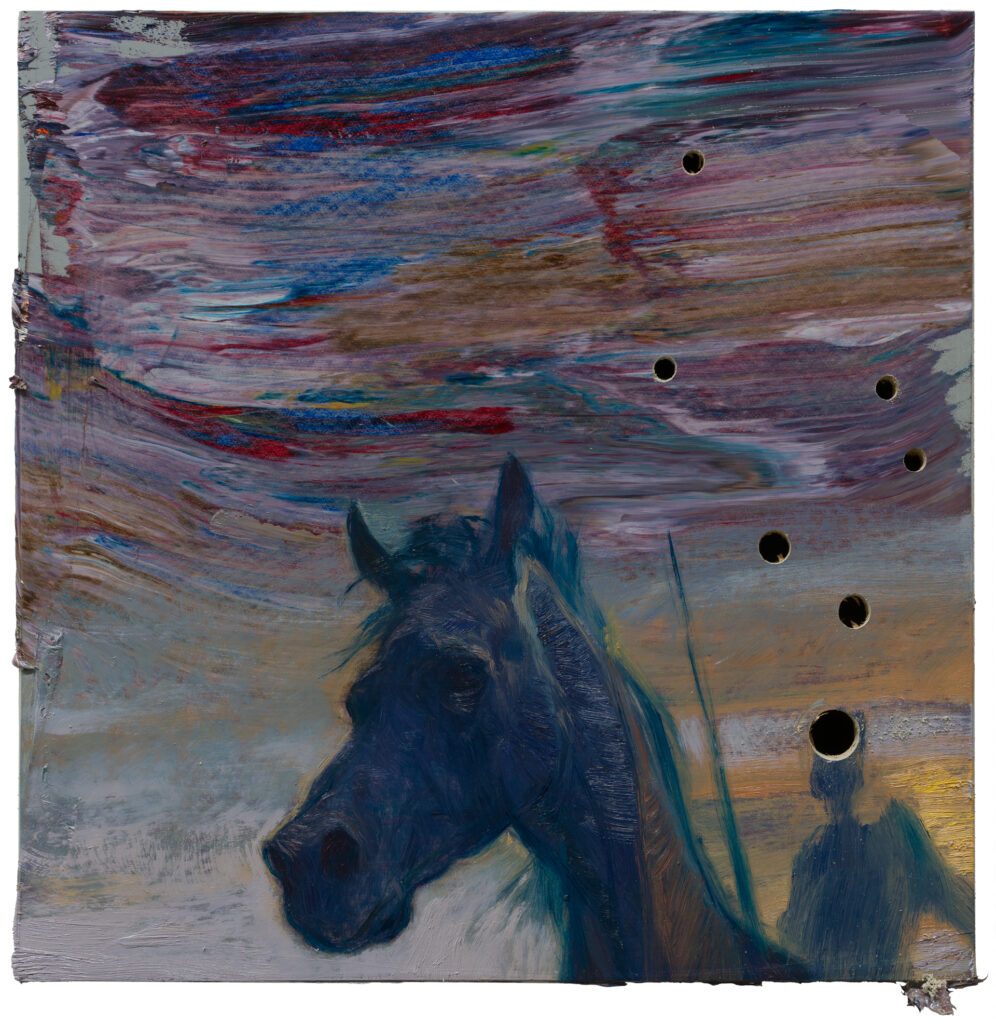

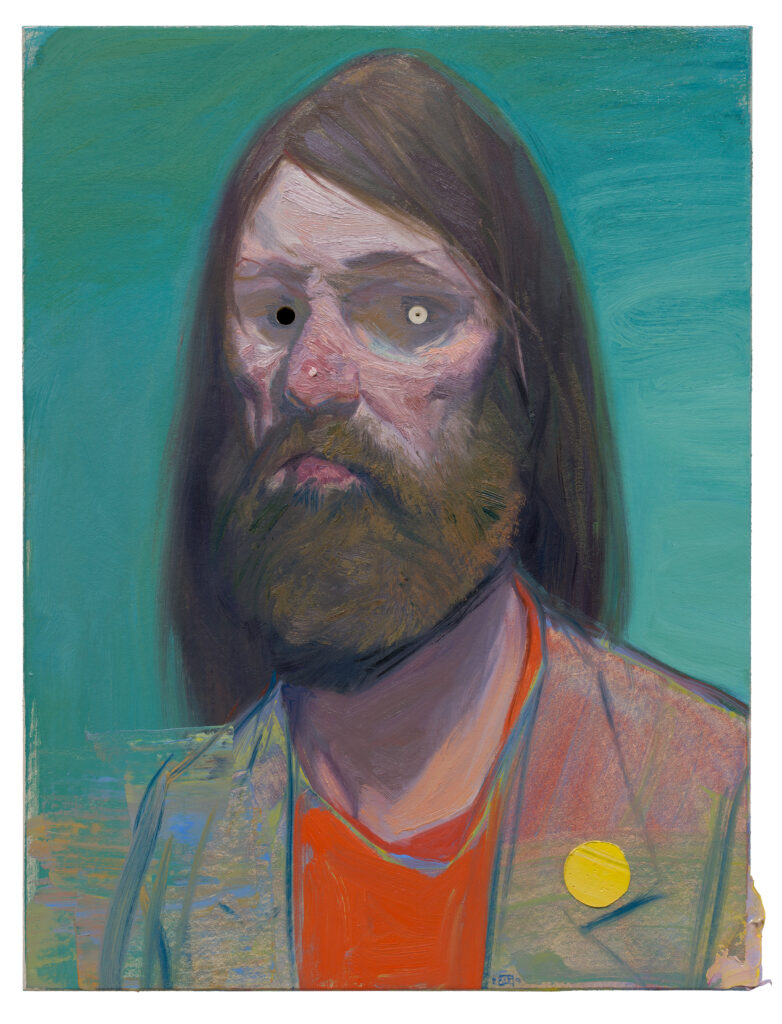

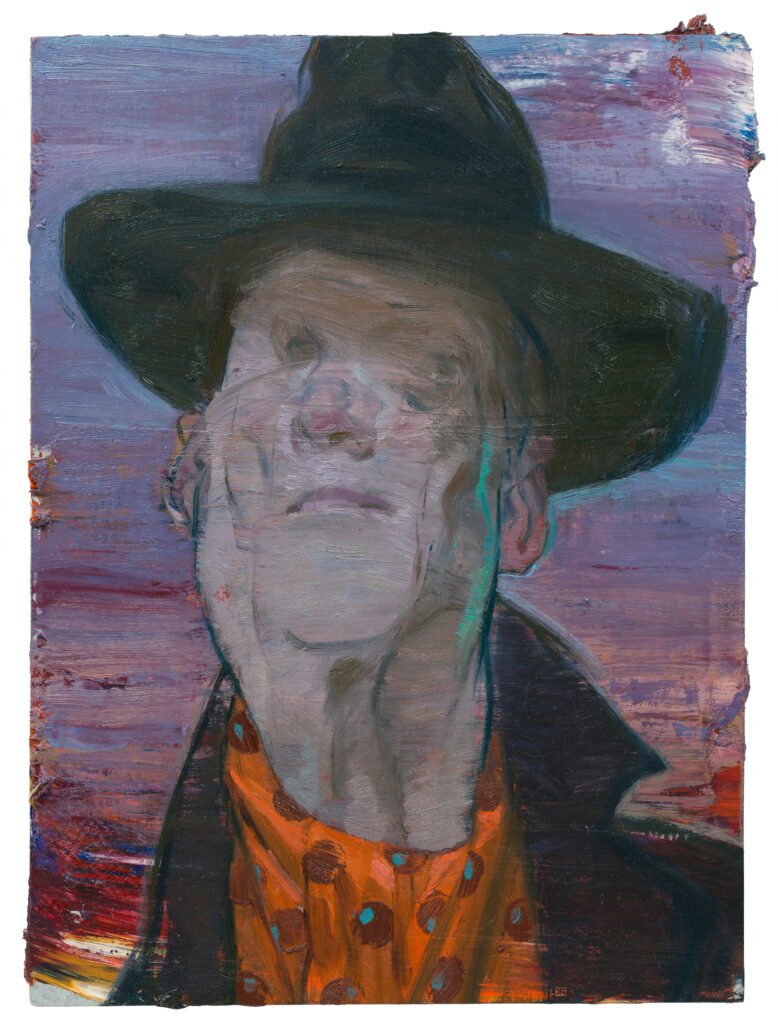

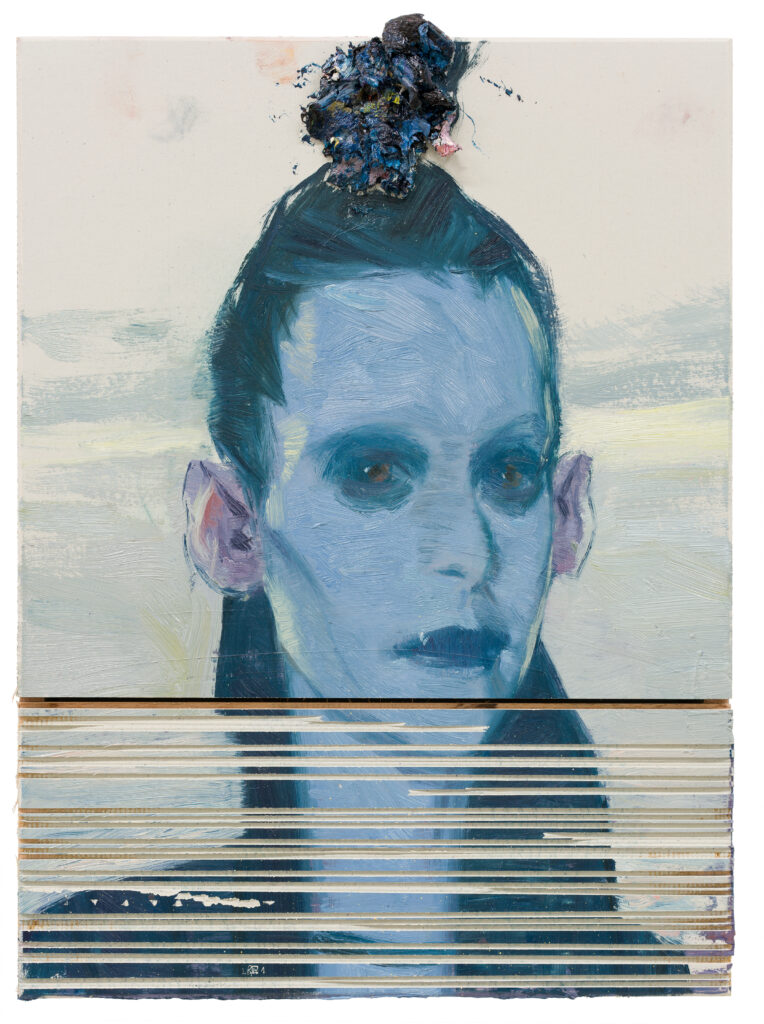

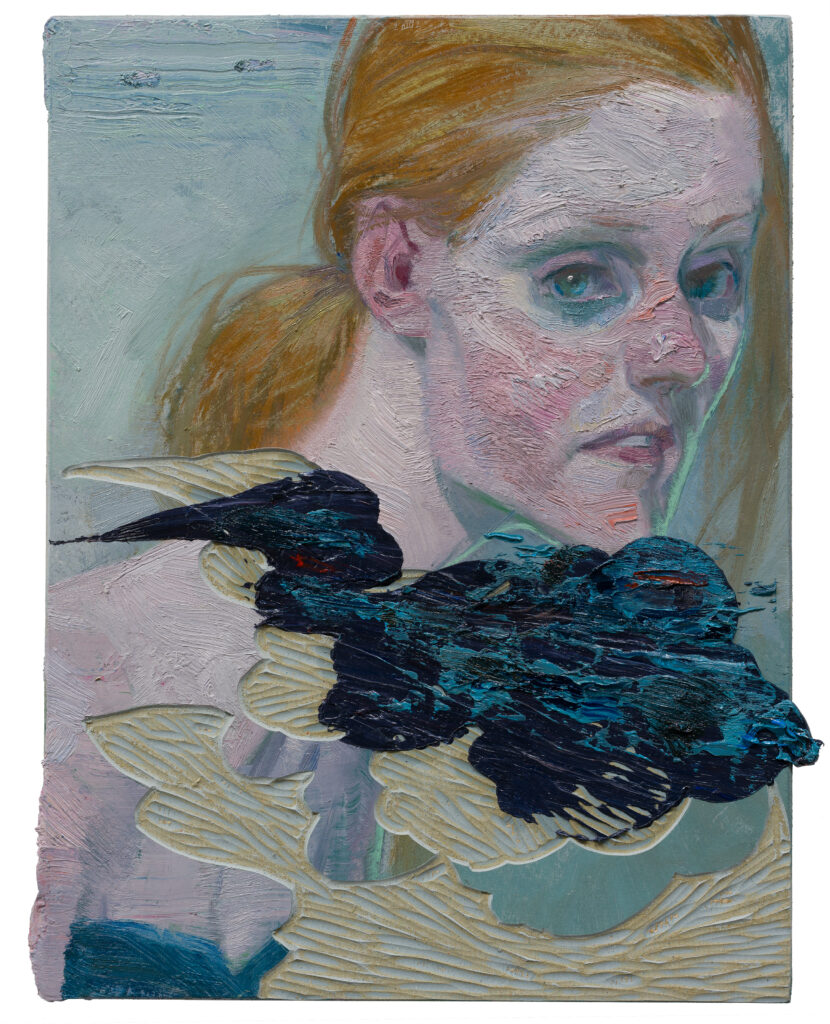

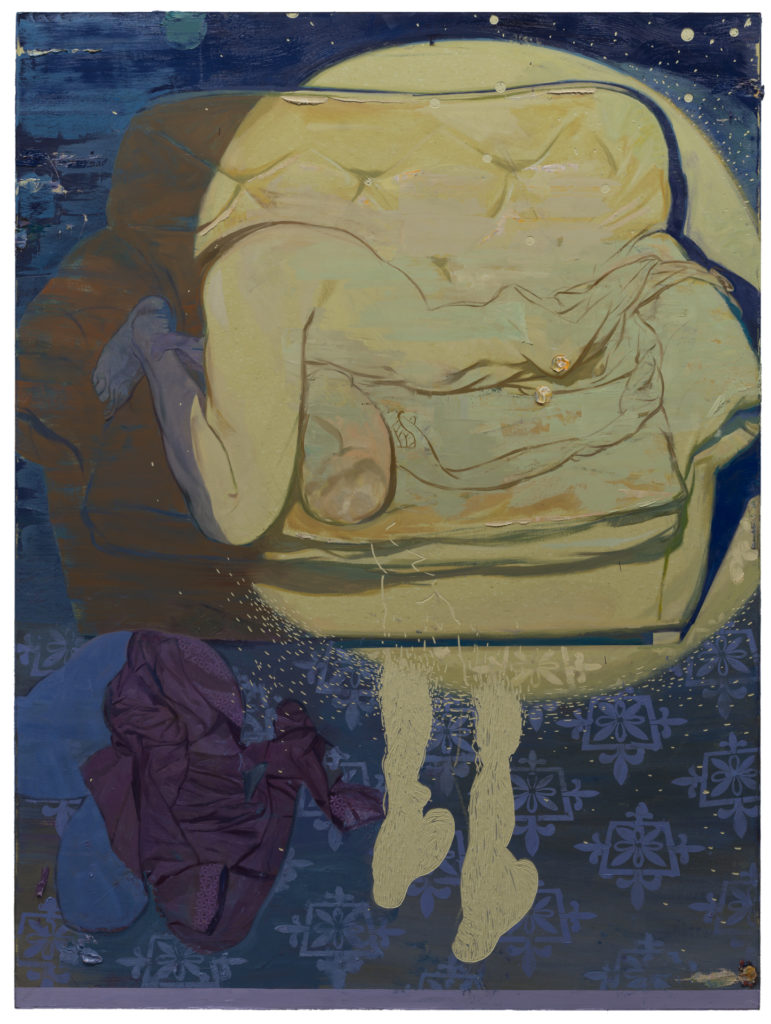

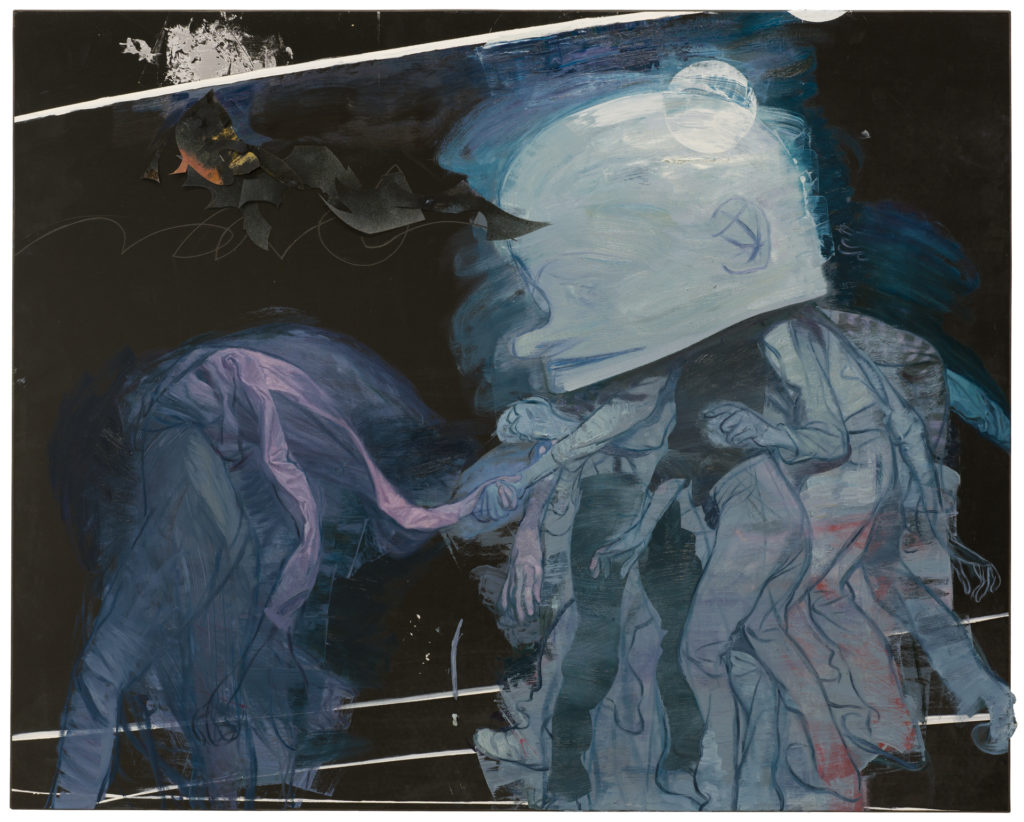

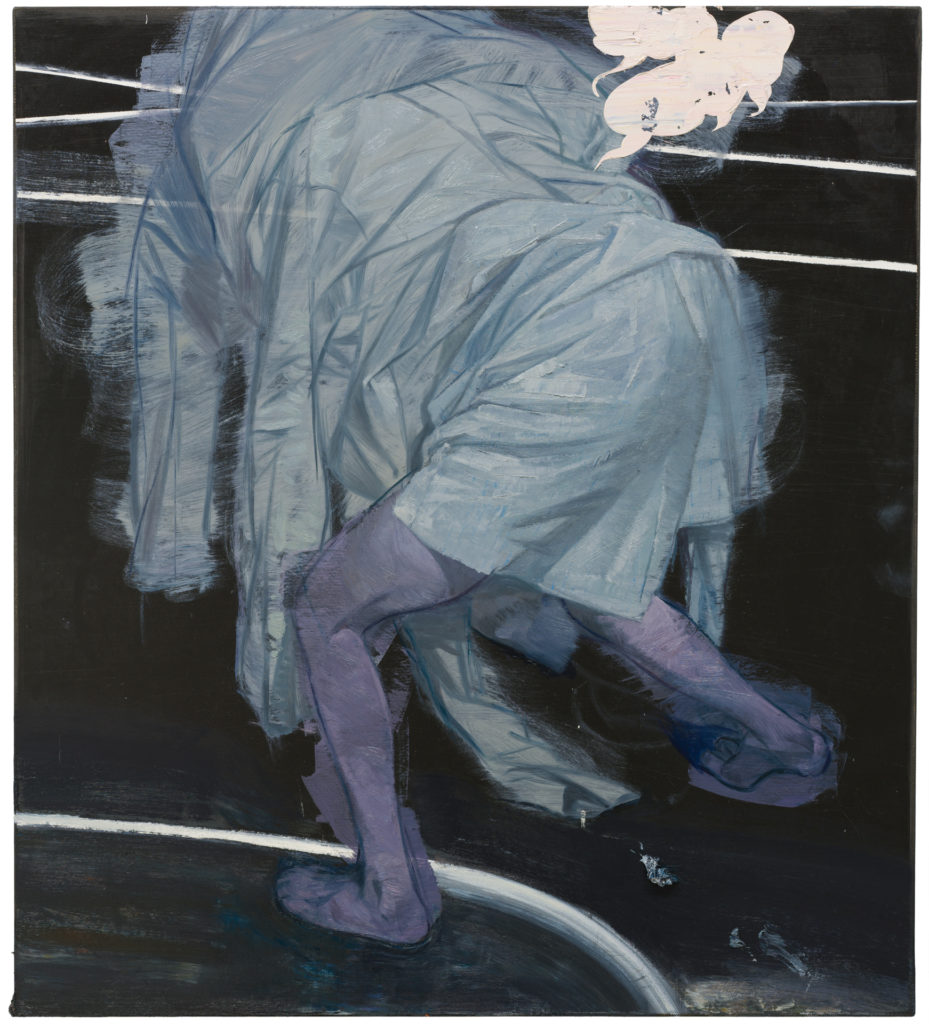

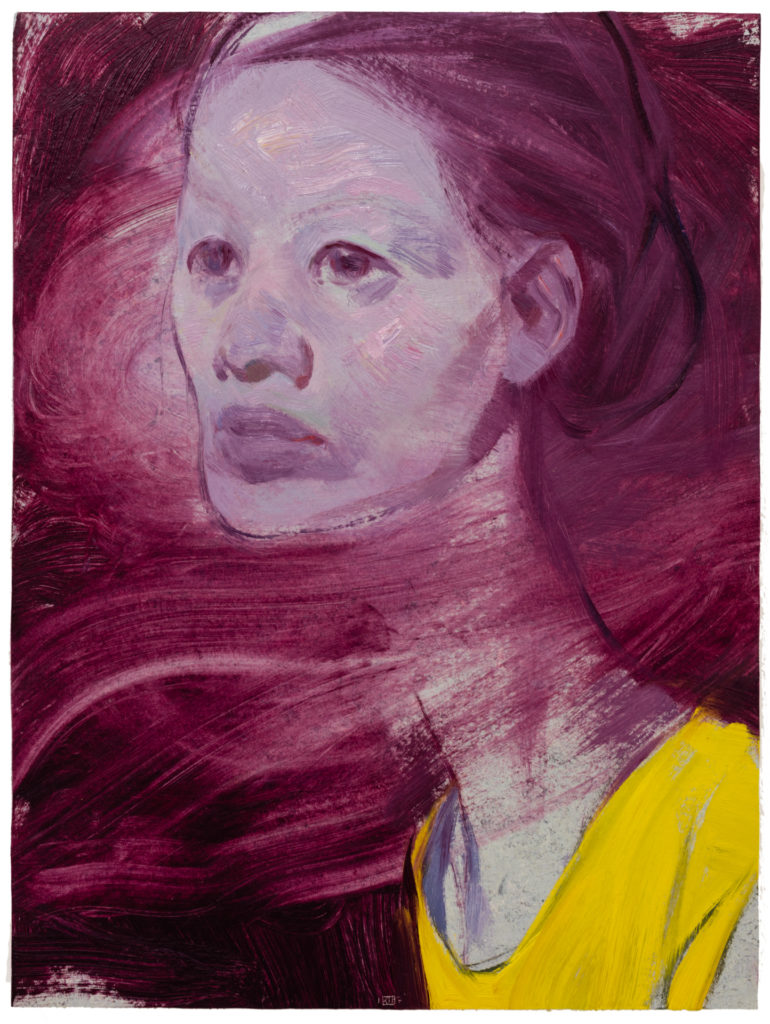

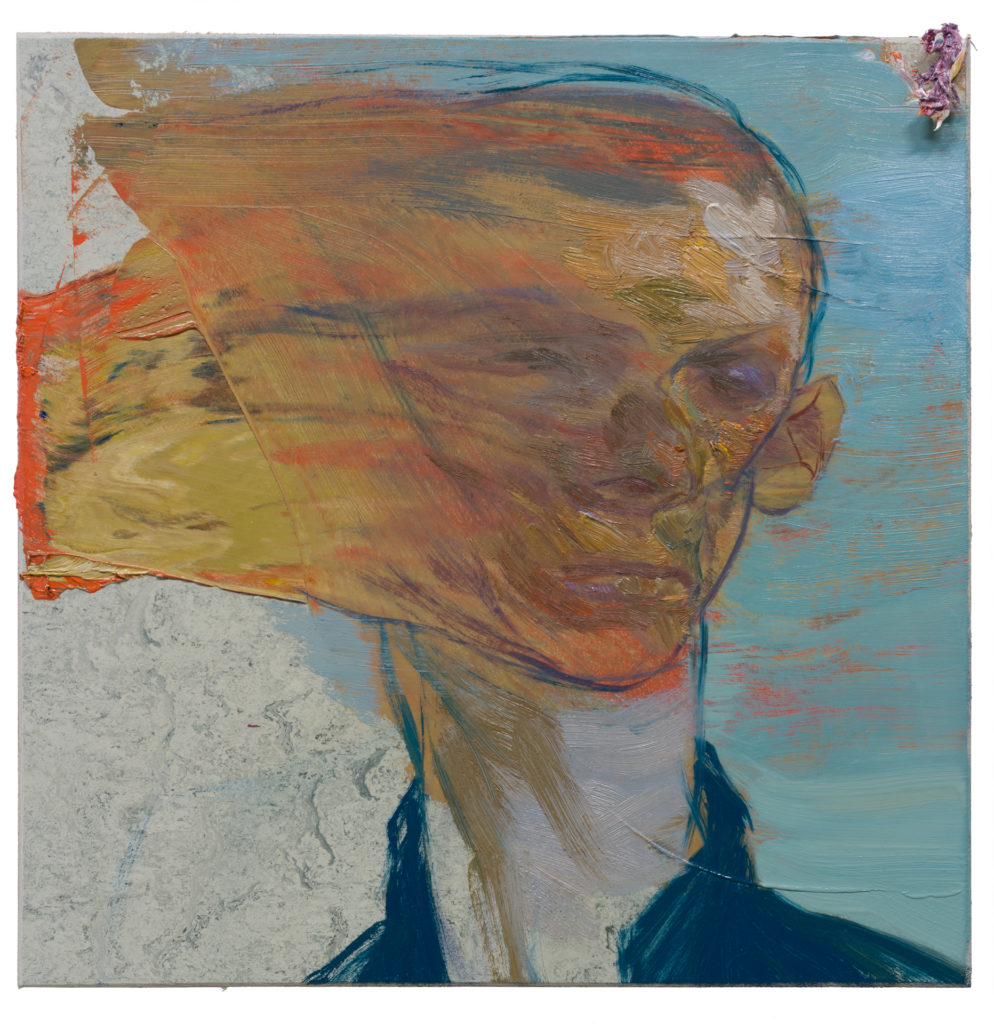

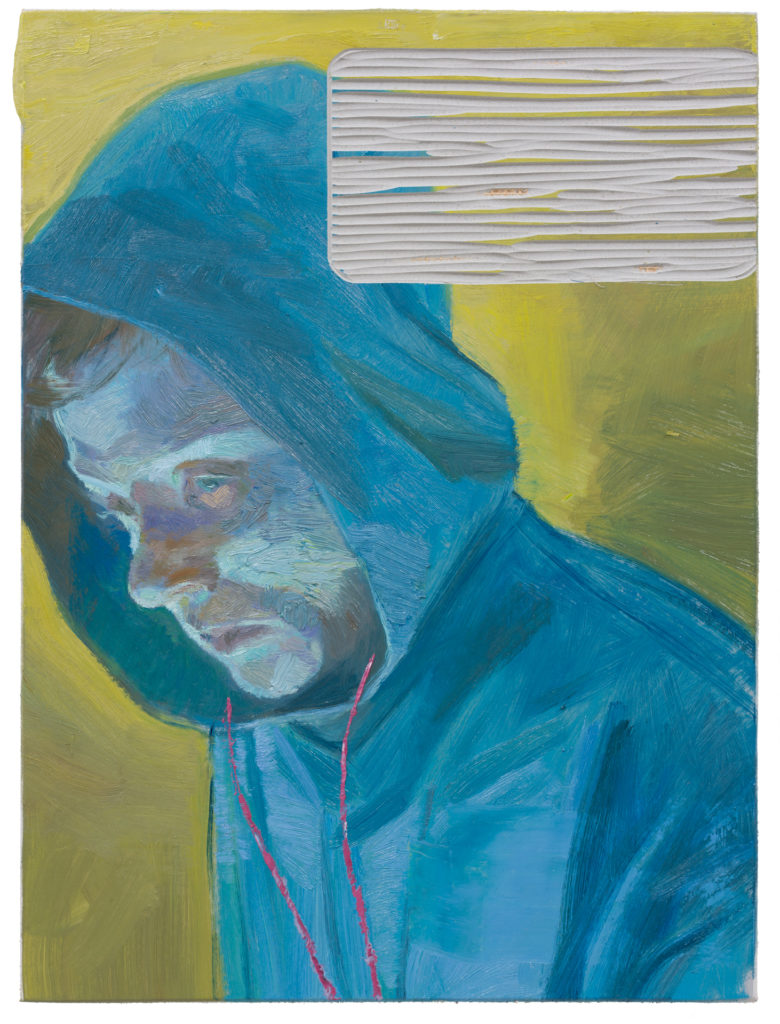

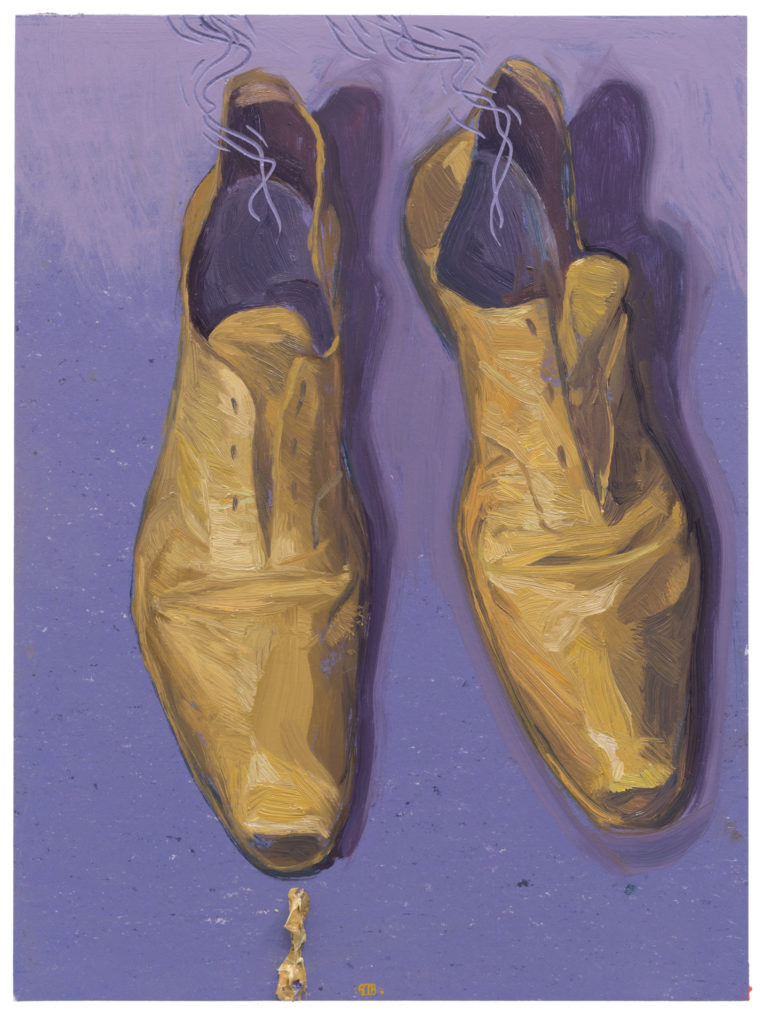

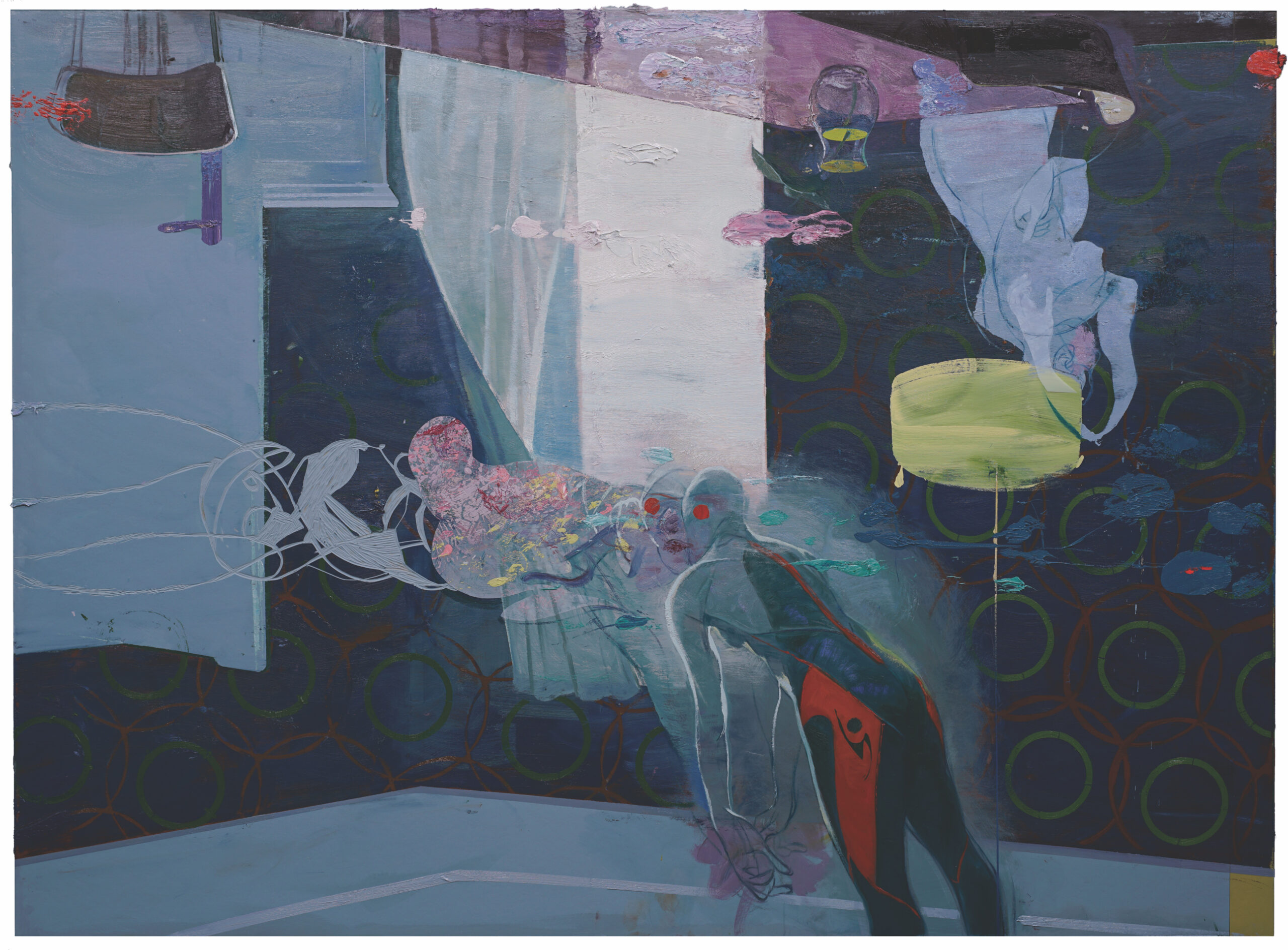

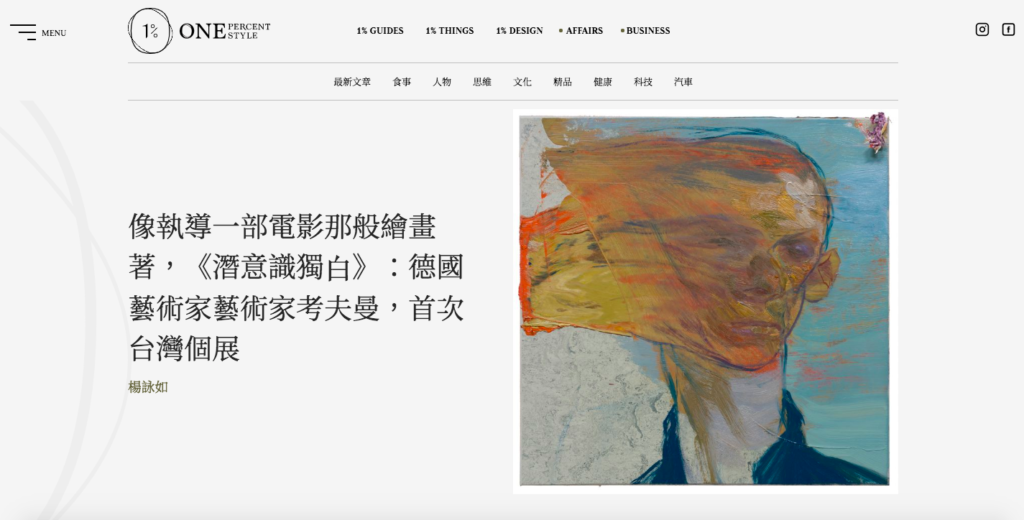

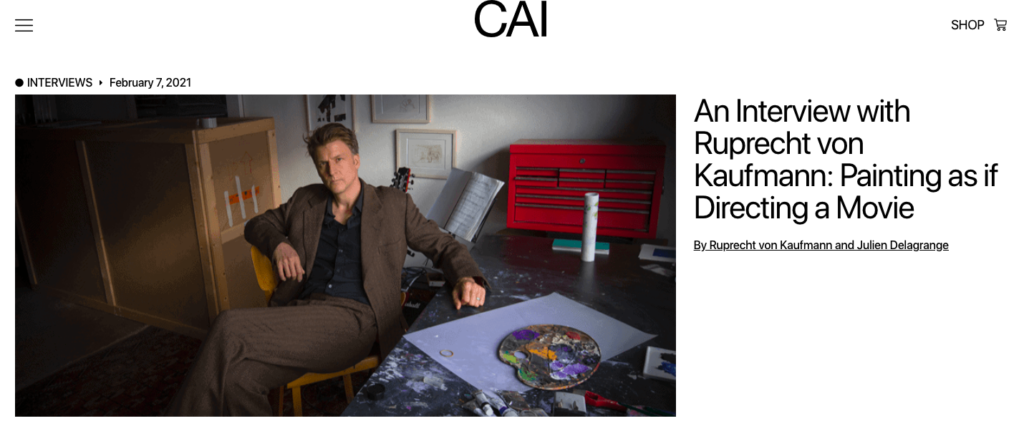

Ruprecht von Kaufmann uses oil paints to create works, including paintings, sculptures and works on paper. His creations are inspired by life experiences.More often, he uses reading literature, music, and movies to trigger various images and imaginations in his mind. Movies are particularly influential. In comparison to the temporal narrative and interweaving voices found in film, painting is a static medium. Kaufmann introduces a division between the before and after in his paintings, thereby unlocking more possibilities for expression. He anticipates that viewers, guided by the composition of the images, will experience strong emotional reactions. Painting, as the result of a series of continuous decisions, simultaneously bears the weight of unexpected imagery. His works often feature repeatedly thickly applied and blurred faces, alluding to unrestricted and open-ended character representations. Although adept at observing and capturing human figures, Kaufmann does not create traditional "portraits"; the faces depicted do not represent specific individuals but rather embody archetypal figures. Through the continuity of low saturation and subdued colors, Kaufmann excels at capturing profound personal moments and individual vulnerability, hinting at a universal human experience.

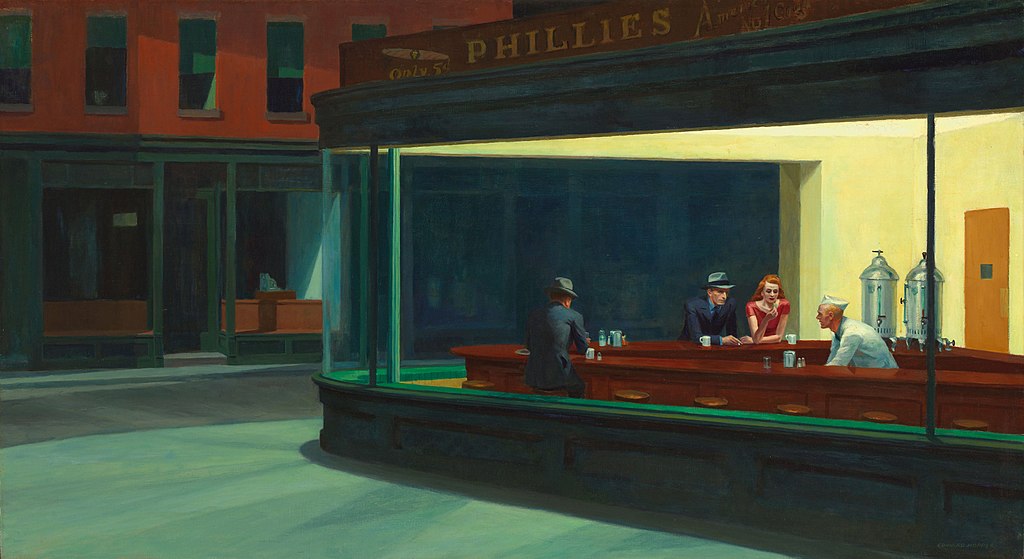

Figurative Art refers to works whose images are based on objects from the real world, incorporating various recognizable elements while infusing the artist's perspectives and thoughts. In contrast to classical portraiture, Francis Bacon's Figurative Art, influenced by Greek classical tragedy, expresses the cruelty, violence, and fear inherent in human nature. The contorted facial features in Bacon's works convey a sense of vanished and unbalanced states, depicting the haunting souls of the walking dead. In Kaufmann's restrained and delicate approach to Figurative Art, he employs an open and humorous style to portray the contradictions and losses of contemporary individuals. His creations seamlessly blend surrealism with absurdity, addressing themes of personal alienation and loneliness. Contrasting with Edward Hopper's 1940s paintings depicting tranquil scenes, individuals in windows, gas stations, and restaurants are depicted in contemplation, experiencing a sense of mutual alienation. Similarly, contemporary Norwegian artist Lars Elling's depiction of a fantastical world where reality and illusion intertwine presents incomplete experiences of the surrounding environment, with elusive shadows reappearing. In the realm of classic literature, Albert Camus's Absurdism creates a sense of solitude, spiritual alienation, and the absurd reality where humanity is powerless to do both good and evil. Alternatively, David Lynch, a contemporary film auteur, with his eerie and surreal style, crafts dreamlike imagery. Like other creators spanning eras, Kaufmann's storytelling prowess, coupled with a style rich in dark humor and intense melancholic hues, reflects our behavior, thoughts, and emotions in the turbulent and uncertain contemporary society.

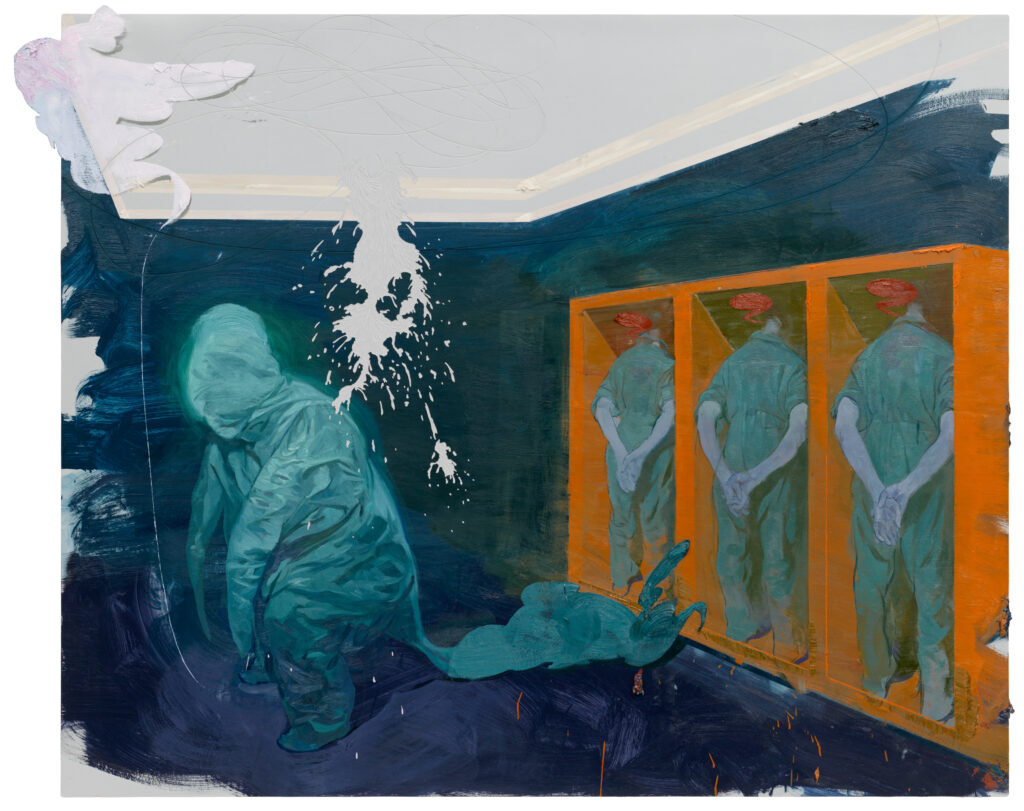

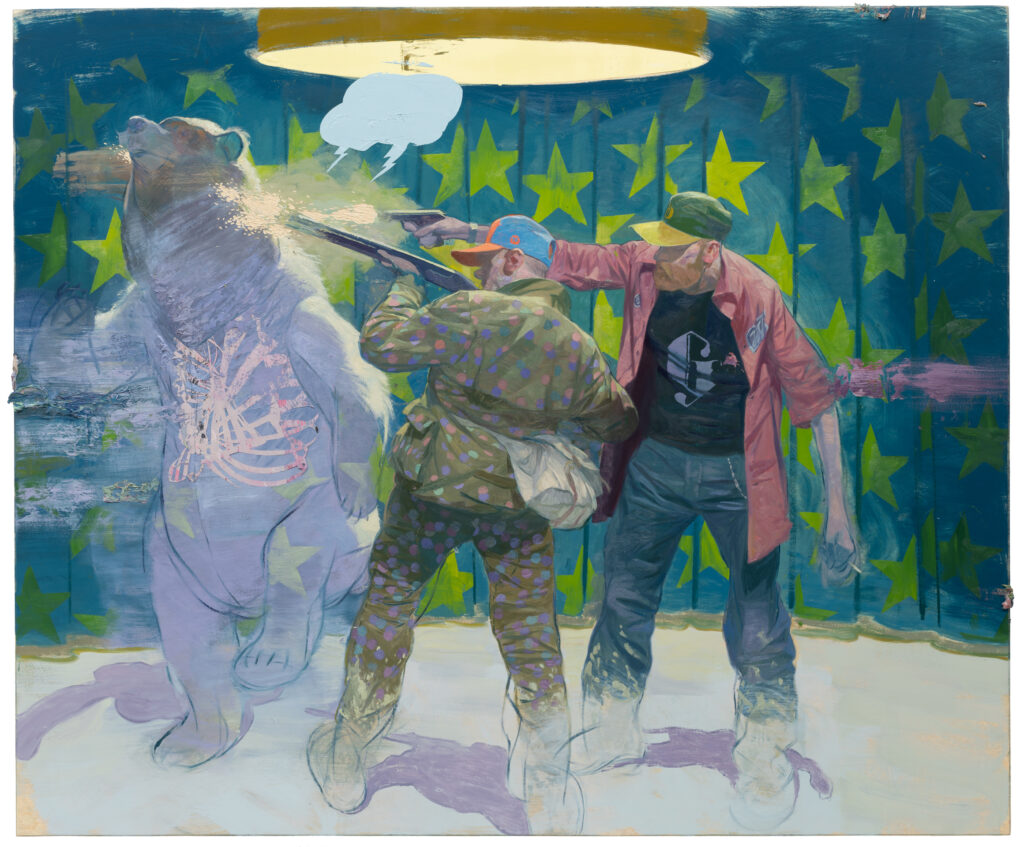

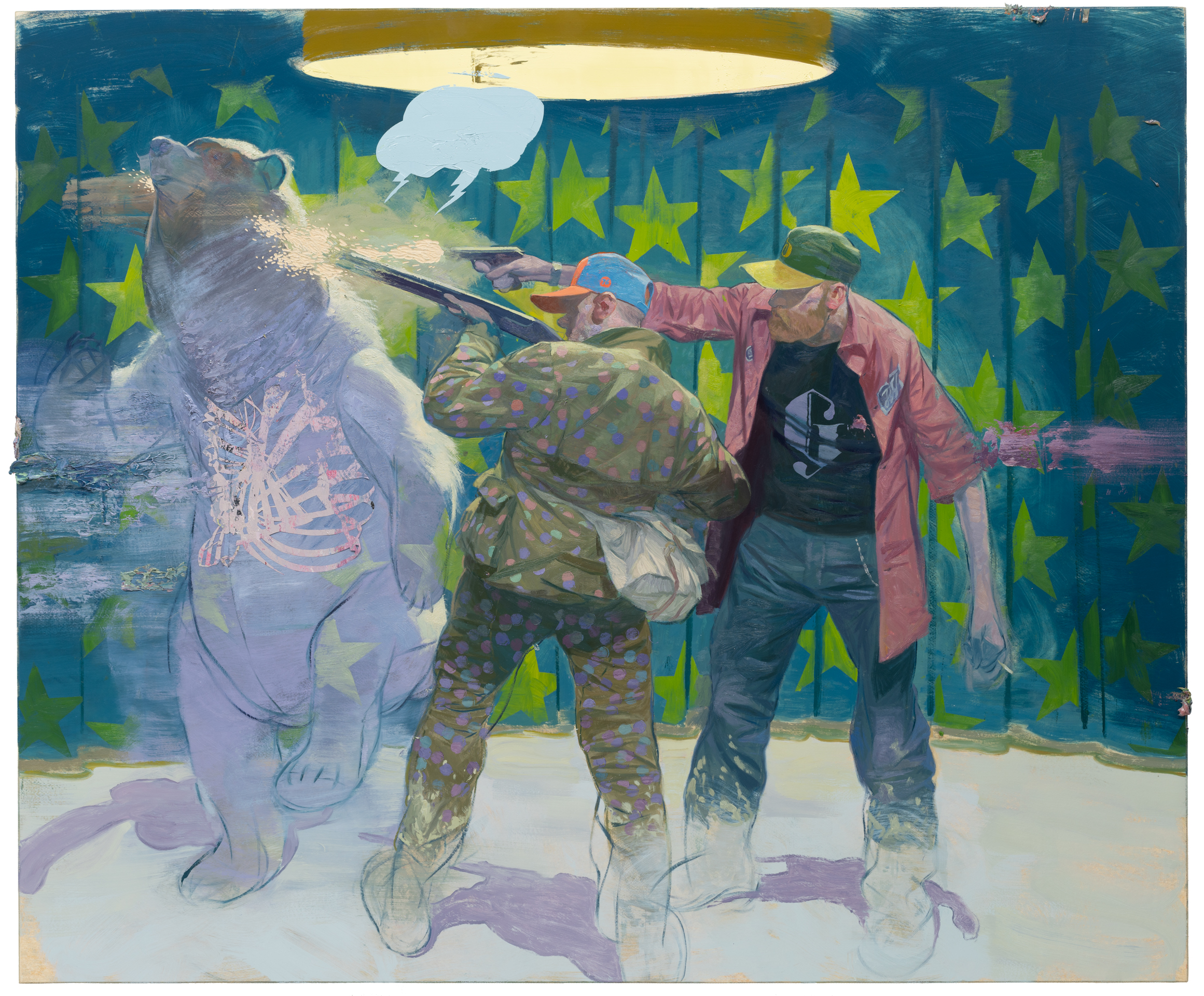

In 2022 and 2023, Kaufmann held solo exhibitions at Bluerider ART Taipei·DunReni and Bluerider ART Shanghai·The Bund, exhibit a series of representative works. Large-scale pieces such as "State of the art" (2015) and "Precious" (2015) draw inspiration from classical painting's refined compositions, unfolding a series of magical and realistic objects and figures that create a poetic atmosphere reminiscent of midnight. The work "Die Gefahrten" (2015) draws inspiration from Homer's epic poem "The Odyssey," symbolizing the artist's journey of seeking ideals, belonging, and self-expression through the ten-year wandering of the Greek hero Odysseus. The piece uses the figure of the "companion" stored in the cabinet as a metaphor for the role of the companion in the hero's story, creating a contrast and advancing the narrative. For example, in "The Odyssey," without companions rowing, Odysseus wouldn't have been able to resist the enchanting song of the Sirens. The artwork "Lying on the Sofa" (2016) narrates the artist's childhood experience of lying on the sofa, gazing at the ceiling, and imagining an inverted world. By creating familiar yet unsettling scenes, it introduces a new perspective, similar to the diver floating in an inverted room, making it challenging to discern the scene. Finally, "Die Wild West Show" (2019) explores the myth of the American Wild West, addressing humanity's excessive exploitation and reckless destruction of natural resources. Using the image of a strong and independent hunter, the artwork packages human greed, selfishness, and culpability, prompting introspection.

Solo Exhibitions

2023 Leben zwischen den Stühlen´, Buchheim Museum, Bernried

2022 In the Street´, Kristian Hjellegjerde Gallery, London

2022 Monologue, Bluerider ART, Taipei, Taiwan

2021 Just Before Dawn´, Galerie Thomas Fuchs, Stuttgart

2021 Dreamscapes´, Cermak Eisenkraft Gallery, Prag

2020 The Three Princes of Serendip´, Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, London

2020 Inside the Outside´, City Gallery Gutshaus Steglitz, Berlin

2019 Inside the Outside´, UN Headquarters, New York

2019 Inside the Outside´, Museen Böttcherstrasse, Bremen

2019 Die drei Prinzen von Serendip´, Kunstsammlung Neubrandenburg, Neubrandenburg

2019 Die Augen fest geschlossen´, Galerie Thomas Fuchs, Stuttgart

2018 Die Evakuierung des Himmels´, Kunsthalle Erfurt, Erfurt

2018 Liederbuch´, Galerie Thomas Fuchs, Stuttgart

2017 Event Horizon´, Kristin Hjellegjerde Galelry, London

2016 The God of Small and Big Things´, Galerie Crone, Berlin

2016 Phantombild-Blaupause´, Nordheimer Scheune, Nordheim, Germany

2015 Grösserbesserschnellermehr´, Forum Kunst, Rottweil

2014 Fabel´, Georg Kolbe Museum, Berlin

2014 Carna(va)l´, Museum Abtei Liesborn, Liesborn

2013 Die Nacht´, Junge Kunst e.V. Wolfsburg

2013 Die Nacht´, Galerie Rupert Pfab, Düsseldorf

2012 Der Ozean´, Galerie Christian Ehrentraut

2011 Altes Haus´, Galerie Rupert Pfab, Düsseldorf

2011 Zwischenzeit´, Neue Galerie Gladbeck, Gladbeck

2010 Äquator Teil I´, Galerie Christian Ehrentraut, Berlin

2010 Herr Lampe´, Bundesbank, Frankfurt

2009 Nebel´, Galerie Christian Ehrentraut

2009 Halbmast´, Philara Collection, Düsseldorf

2008 Ruprecht von Kaufmann´, Galerie Rupert Pfab, Düsseldorf

2007 Eine Übersicht´, Konrad-Adenauer-Foundation, Berlin

2006 Bathosphere´, Ann Nathan Gallery, Chicago

2006 Bathosphere´, Kunstverein Göttingen

2006 Als mich mein Steckenpferd fraß´, Galerie Christian Ehrentraut, Berlin

2005 Bildwechsel´, Galerie Christian Ehrentraut, Berlin

2005 Neue Zeichnungen´, Kunstschacht Zeche Zollverein, Essen

2003 `Of Faith and Other Demons´, Claire Oliver Fine Arts, New York

Group Exhibitions

2023 Foreshadow, Bluerider ART Shanghai, Shanghai, China

2022 `On the Wall´, Building Gallery, Mailand

2022 `Das Eigene im Fremden – Einblicke in die Sammlung Detlev Blenk´, Museum Bensheim

2021 `Gefühle r(aus)! Global Emotion´, Motorenhalle, Dresden

2020 `Neue Wilde und Andere aus der Sammlung Stefan Neukirch´, Coesfeld

2019 `Feelings´, Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, Germany

2019 `Metaphysica´, Haugar Art Museum, Tønsberg, Norway

2019 `Birkholms Echo´, Faaborg Museum of Art, Faaborg, Denmark

2018 `Contemporary Chaos´, Vestfossen Kunstlaboratorium, Vestfossen, Norway

2018 `Schwarze Romantik´, Künstlerhaus Thurn & Taxis, Bregenz, Topicuv Salon, Prague

2017 `Ecce Creatura´, Kallmann Museum, Ismaning

2017 `Paintingguide NYC´, Booth Gallery, New York, USA

2017 `Schwarze Romantik´, Bukarest, Berlin, Backnag, Bregenz, Prag

2016 `Wahlverwandschaften, German Art since the late 1960s´, National Museum of Latvia, Riga

2016 `Prozac´, Kunstverein Glückstadt, Glückstadt, Germany

2015 `The Vacancy´, Friedrichstr., Berlin

2015 `Kunst Wollen?´, openAEG, Nürnberg

2015 `Du sollst Dir (k)ein Bild machen´, Berliner Dom, Berlin

2015 `Time Lies´, KinoInternational, Berlin

2014 `The Sea´, Brandts Museum, Odense

2014 `Revolution´, Rohkunstbau, Roskow

2014 `Waffensichten´, Museum Galerie Dachau, Dachau

2014 `Malerei am Rand der Wirklichkeit´, Haus am Lützwoplatz, Berlin

2013 `Tierstücke´, Museum Abtei Liesborn

2013 ‘Alles Wasser’, Galerie Mikael Anderson, Copenhagen

2013 ‘Weltenschöpfer’, Museum für Bildende Kunst, Leipzig

2012 `Convoy Berlin´, Bzarsky Gallery, Budapest

2011 `I am a Berliner´, Tel Aviv Museum, Israel

2010 `Werkschau I der Erwine Steinblum Stipendiaten´, Kunst:raum Syltquelle, Rantum / Sylt

2009 `Menschenbilder 1620/2009´, Museum Hoexter-Corvey, Hoexter

2008 `Daydreams & Dark Sides´, Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin

2007 `Stipendiatenausstellung´, Konrad-Adenauer-Foundation, Berlin

2006 `Full House´, Kunsthalle Mannheim

2006 `Gletscherdämmerung`, Eres Stiftung, München

2003 `RePresenting Representation VI´, Arnot Art Museum, New York

2002 `The Perception of Appearance´, The Frye Art Museum, Seattle

2001 `Representing LA´, The Frye Art Museum, Seattle, Art Museum of South Texas and Orange County Museum of Art, LA

Publication

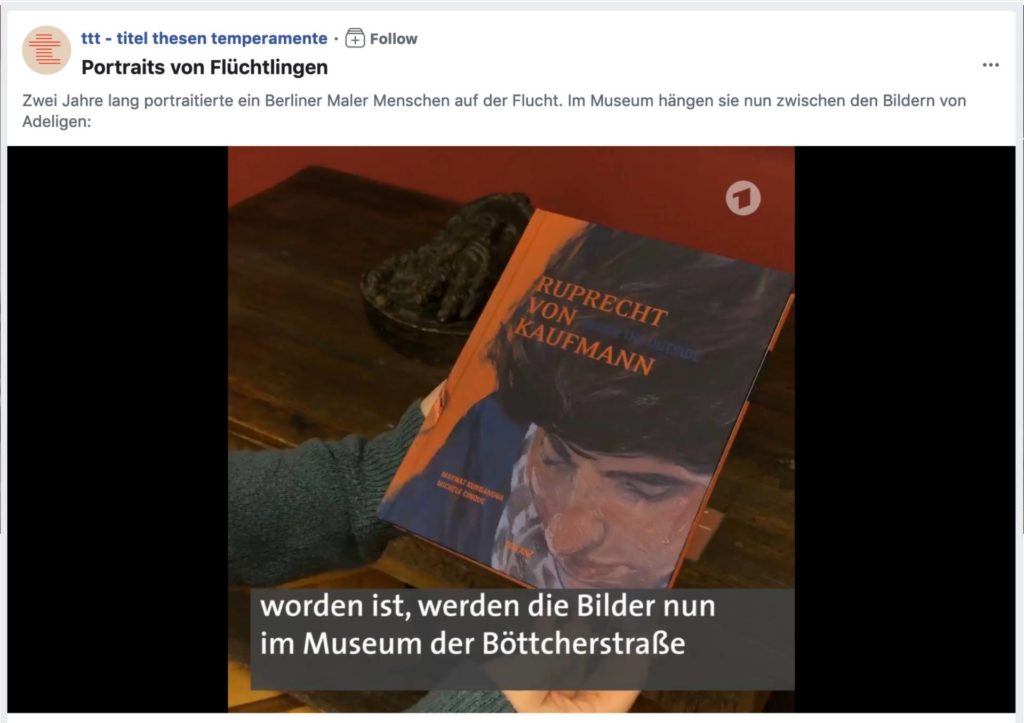

Dissonance – Platform Germany, DCV, Texte: Mark Gisbourne, Christoph Tannert, 2022, ISBN 978-3-96912-060-6

Leben zwischen den Stühlen, Distanz, Texte: Dr. Brigitte Hausmann, Daniel J. Schreiber, Sylvia Volz, 2020, ISBN 978-3-95476-354-2

Inside the Outside, Distanz, Maynat Kurbanova, Michele Cinque, 2019, ISBN 978-3-95476-270-5

Maynat Kurbanova, Michele Cinque, Inside the Outside, Distanz

Magdalena Kröner, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Kunstmarkt

Robert Hughes, Rolf Lauter, Julia Wallner, Ruprecht von Kaufmann 2005-2006, ISBN 978-3-00-020112-7

Leah Ollman, Los Angeles Sunday Times, ‘Painting a Mirror for Humanity’, 16. Juni 2002

Garrett Holg, Art News, ‘A futurist Manifesto’, Ruprecht von Kaufmann at Ann Nathan Gallery Chicago’, Januar Ausgabe 2002

Collection

Collection of the Federal Republic of Germany

Collection of the German Bundestag

Collection of the National Bank of the Federal Republic of Germany, Frankfurt

Coleccion Solo, Madrid

Collection Ole Faarup, Kopenhagen

Collezione Coppola, Vicenza

Hort Family Collection, New York

Uzyiel Collection, London

Sammlung Philara, Düsseldorf

Sammlung Hildebrand, Leipzig

Sammlung Holger Friedrich, Berlin

Sammlung Museum Abtei Liesborn, Liesborn

Sammlung Veronika Smetackova, Pragu