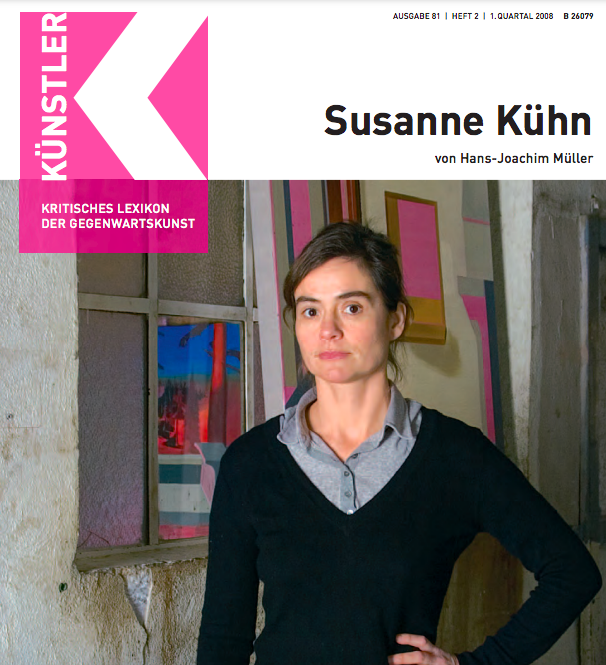

(Germany , b. 1969)

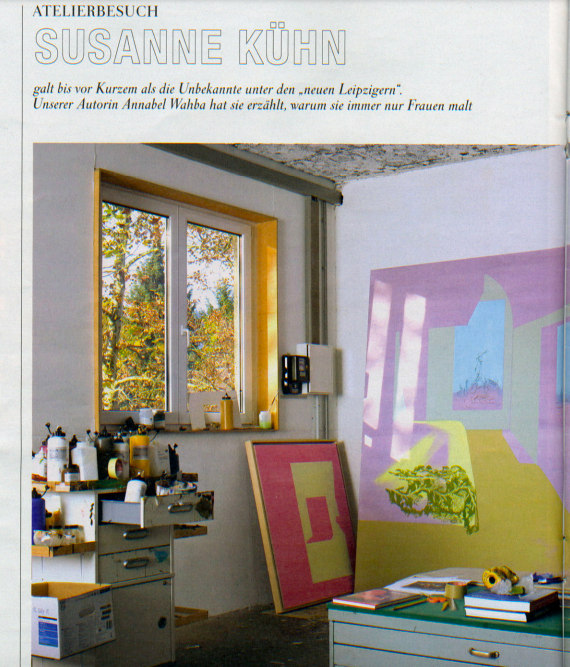

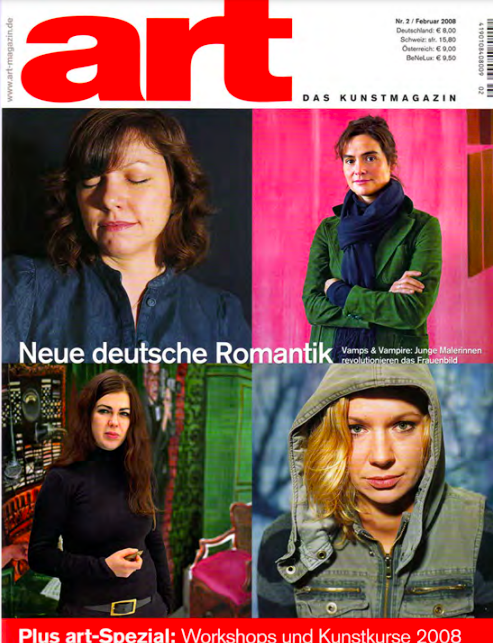

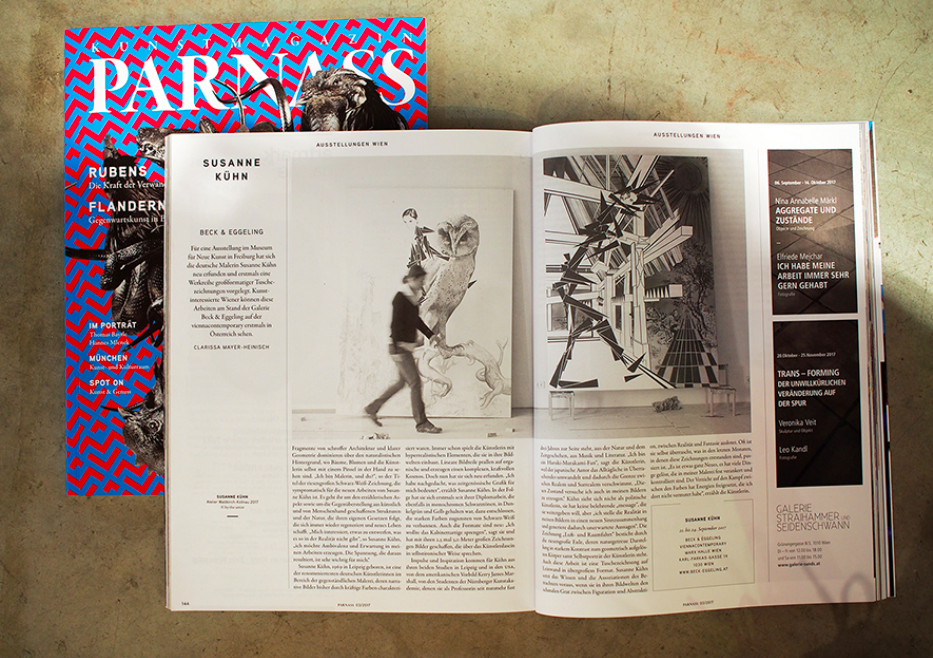

Susanne Kühn was born in Leipzig, Germany, currently lives and works in Freiburg and Nuremberg, Germany. She holds a Master's degree in Painting and Printmaking from the Leipzig Academy of Visual Arts, later pursuing studies at the New York Academy of Visual Arts, Hunter College, and was awarded a scholarship from the Harvard University Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies. Central to Kühn's practice is her highly animated and vivid execution of a precise level of craftsmanship through which she interweaves various painterly vernaculars and styles. Via this aesthetic approach, she engages with the history of painting from a female perspective, as well as exploring everyday life and futuristic narratives in her current work. Kühn's work has been showcased in solo exhibitions at various renowned venues, including the Gemäldegalerie der Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Vienna, the OMI International Arts Center in Ghent, New York, Haunch of Venison in London, UK, Sala Uno Contemporary Arts Centre in Rome, the Harvard Radcliffe Institute in Cambridge, USA, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Denver, USA, the Museum für Neue Kunst in Freiburg, etc. Her work is represented in collections worldwide including viz. the Busch-Reisinger Museum Collection / Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA, USA, the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, the Knoxville Museum of Art, the Harvard Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, FRAC Alsace, France, Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden Germany.. etc.

2022 “Profliferation – Vasa, Auginella & other sprouts”, Galerie für Gegenwartskunst, Ewerk Freiburg

2021 kunstmuseum celle, Germany

2021 Museum fur Neue Kunst Freiburg

2008 Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, USA

2019 House for a Painting, FRAC Alsace, France

Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City

Collected by Academy of Fine Arts Vienna

UBS Art Collection

Collected by Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA

Jan van Eyck, Arnolfini Portrait, 1434

Albrecht Dürer, Self-Portrait, 1500

Cindy Sherman,Untitled (#193),1989

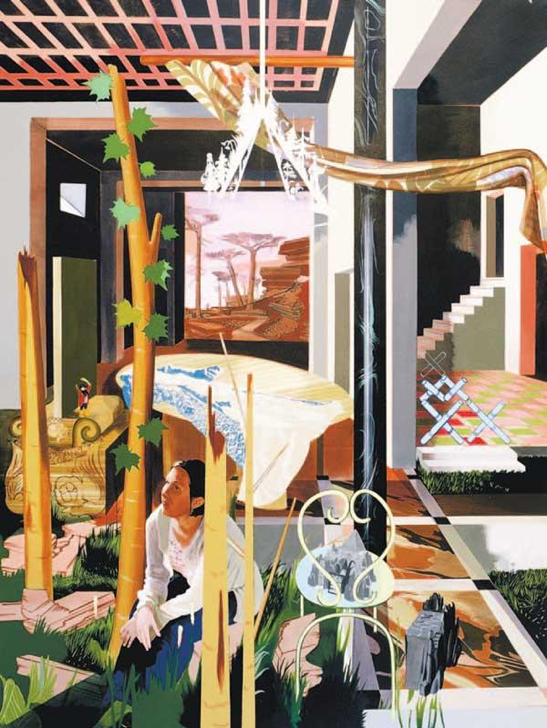

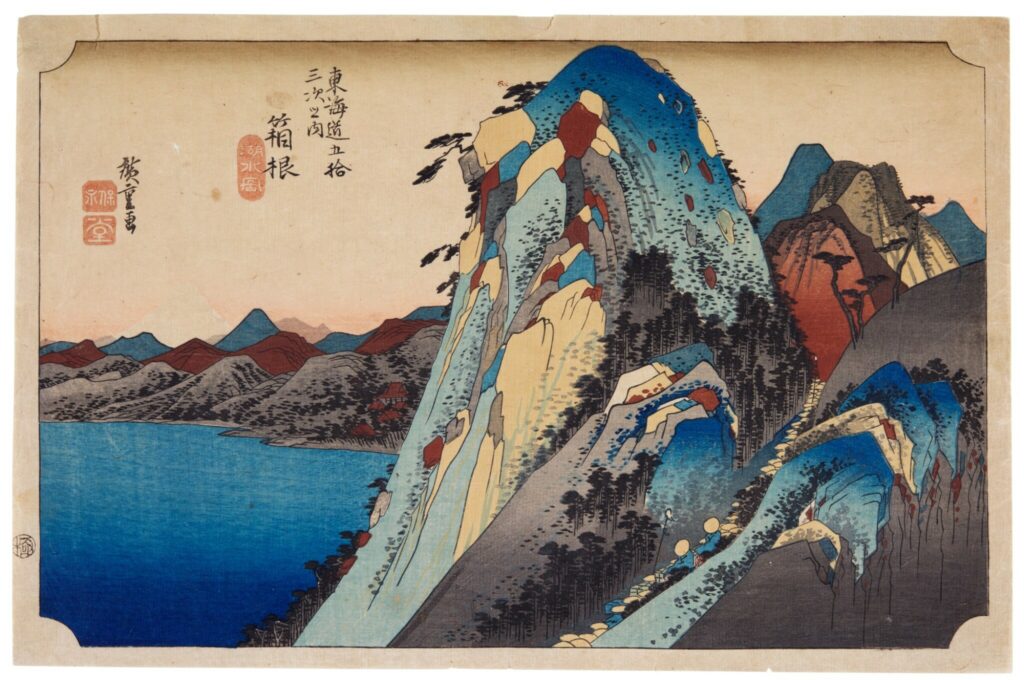

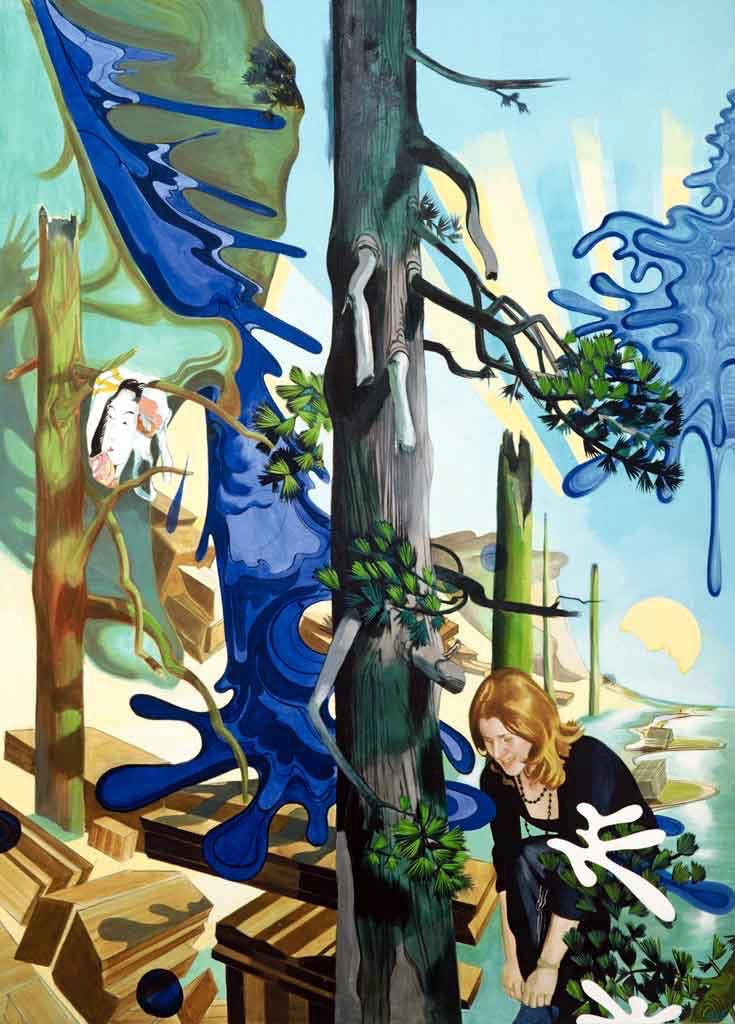

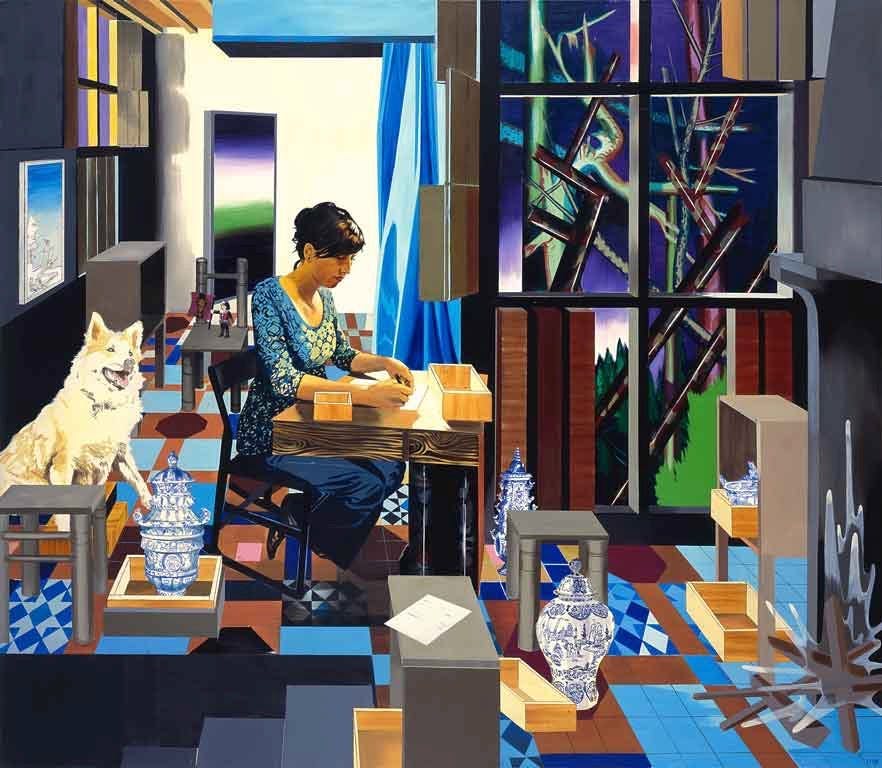

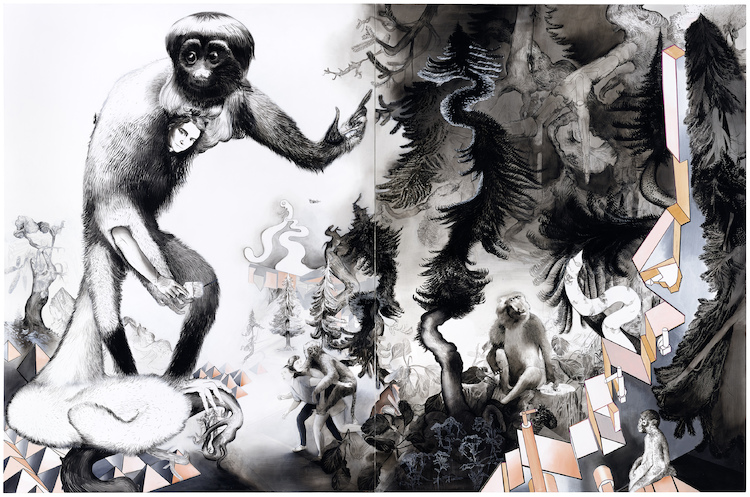

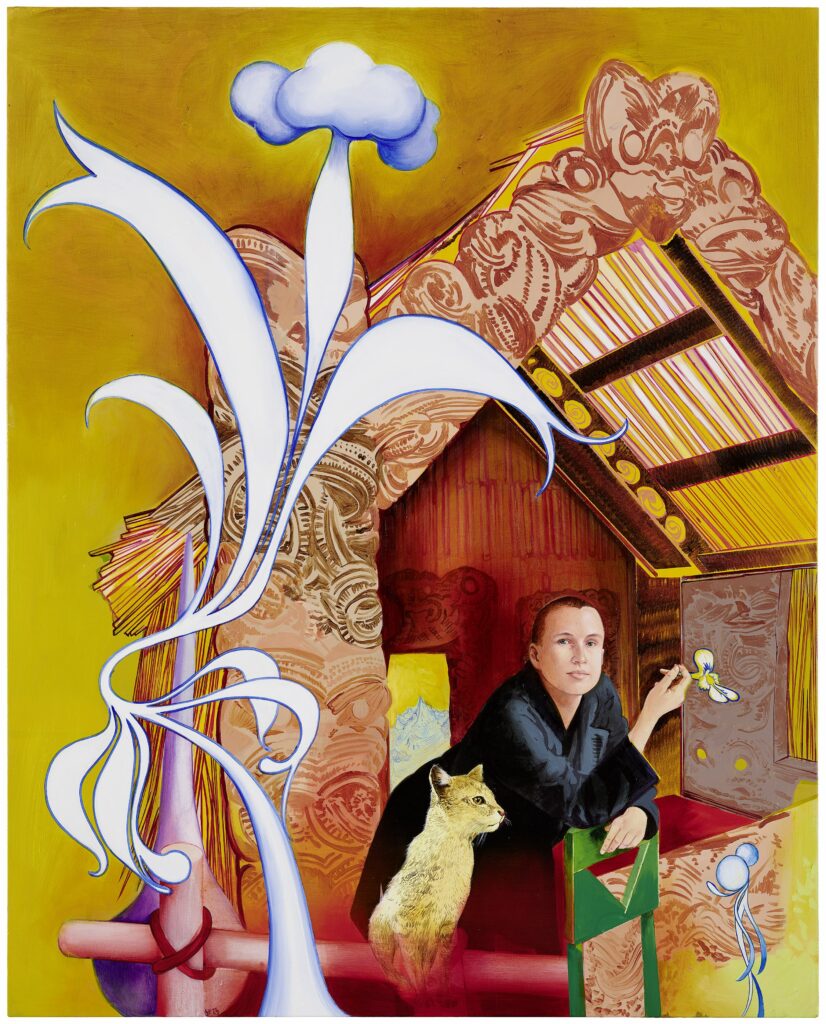

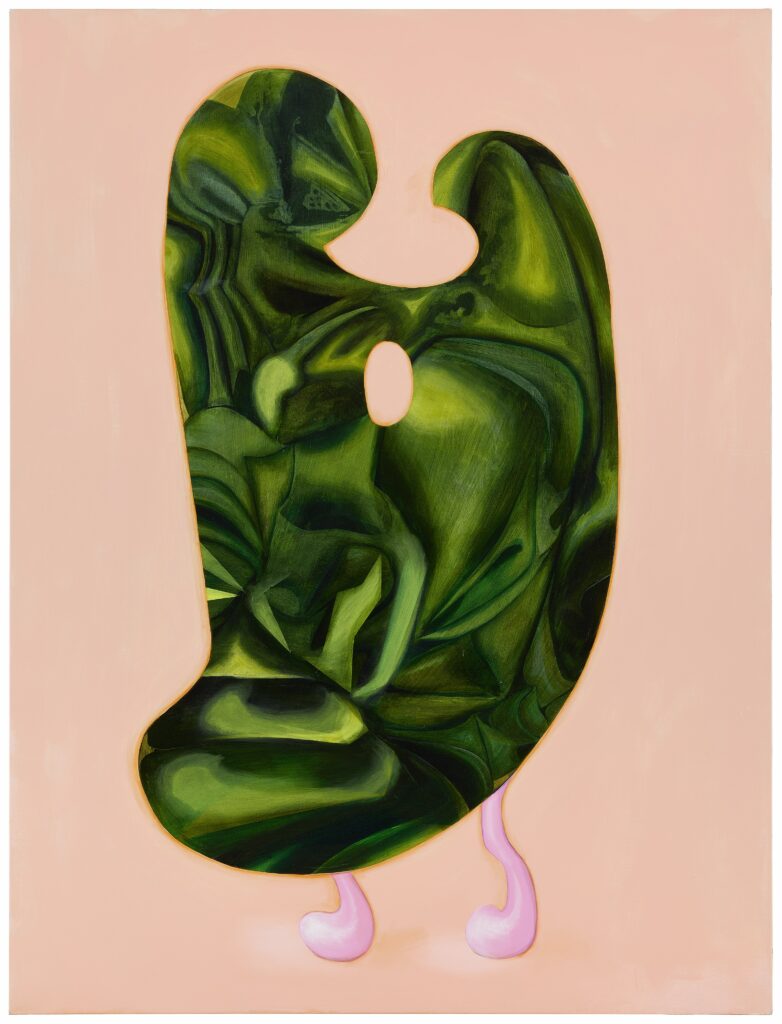

Susanne Kühn's realistic paintings transcend and juxtapose elements from different times and spaces. Her works are characterized by strong, clear contours and vibrant colors, combining naturalistic elements with highly artificial forms. She utilizes various media acrylic pigments, mixed media, printmaking, and ceramics. Her works often depict mountains, moonlight, decayed wood, animals, and other natural elements, developed her own color palette, cleverly combining historical elements in a whimsical yet realistic manner. Artificial spaces are central to Kühn's works, where she frequently references compositions from the Renaissance period, this results in an illusion of precision in reality through layers of space, atmosphere, and light. Ranging from classical to contemporary, Kühn's works provide viewers with a sense of elements crossing different times and spaces, presenting the illusion of reality from classical perspectives combined with the experiential atmosphere of virtual reality. Kühn invites viewers to explore her created virtual world. In her surreal apocalyptic scenes, the encounter between humans, machinery, and monkeys metaphorically represents the rise and fall of civilization, nature's resistance, and the precarious fate of humanity.

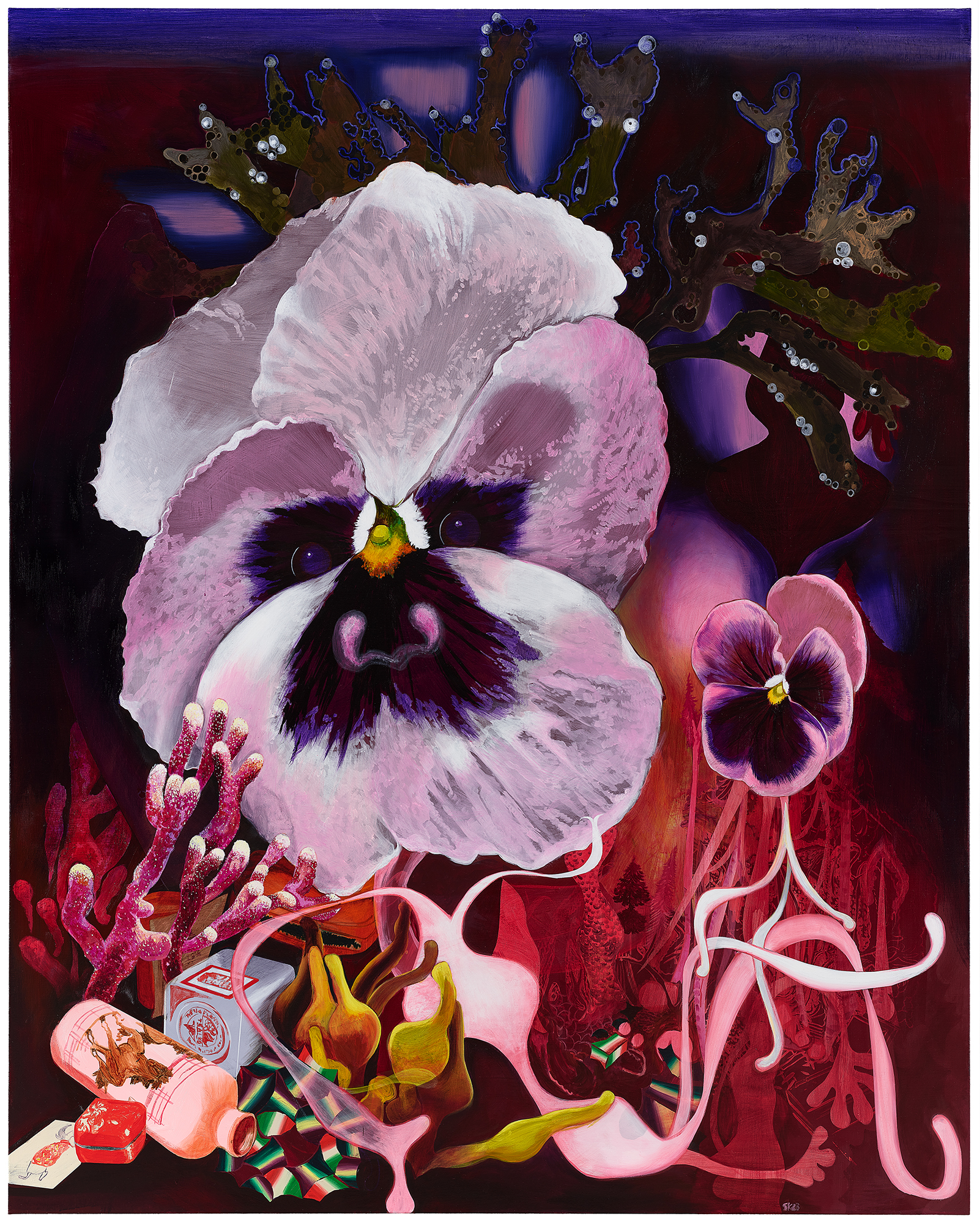

Susanne Kühn|VASA, Smoke and Plant|2023| 200x160cm| Acrylic on canvas

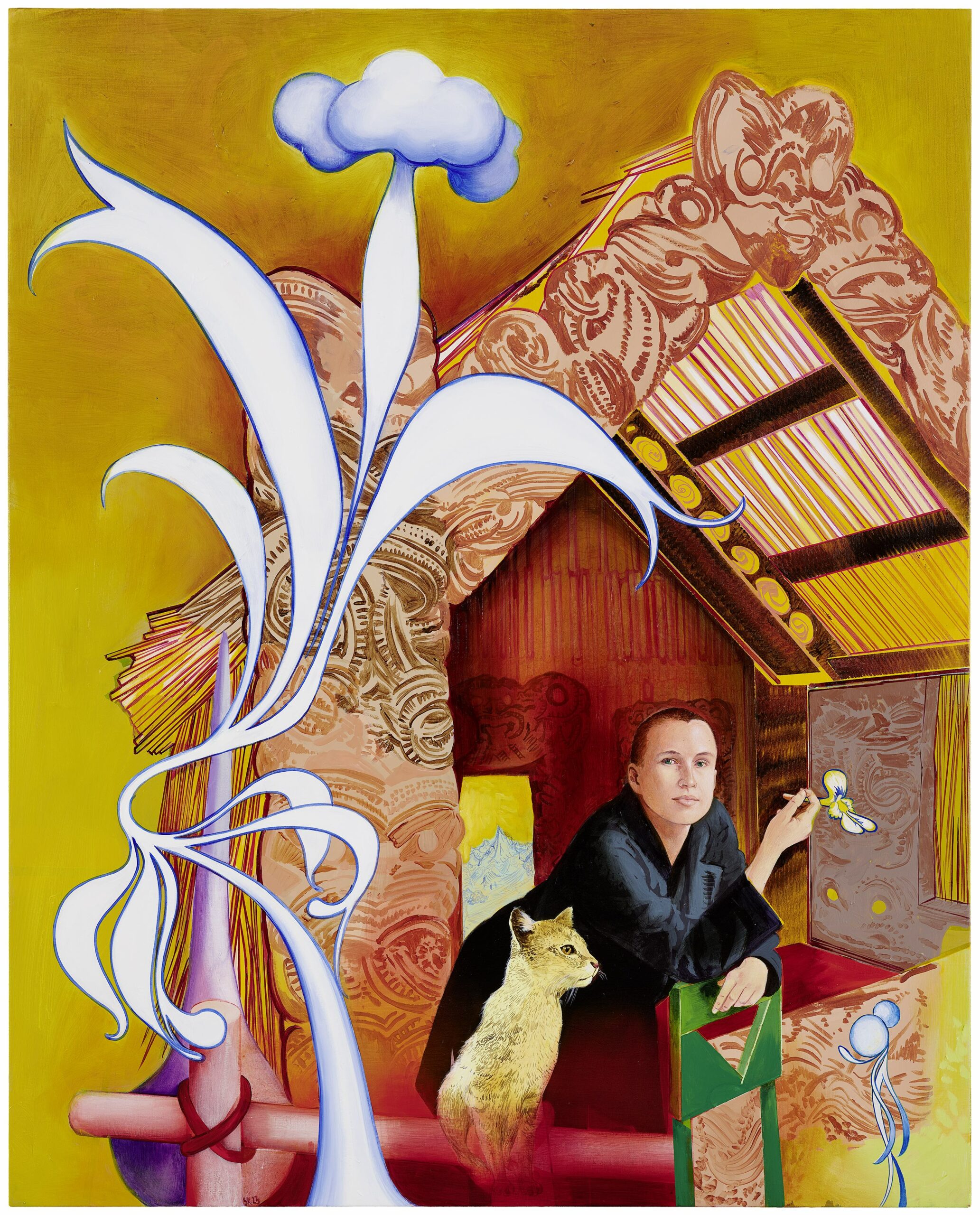

Susanne Kühn|Palette- Palette Konrad Witz| 2022| 250x190cm| Acrylic on canvas

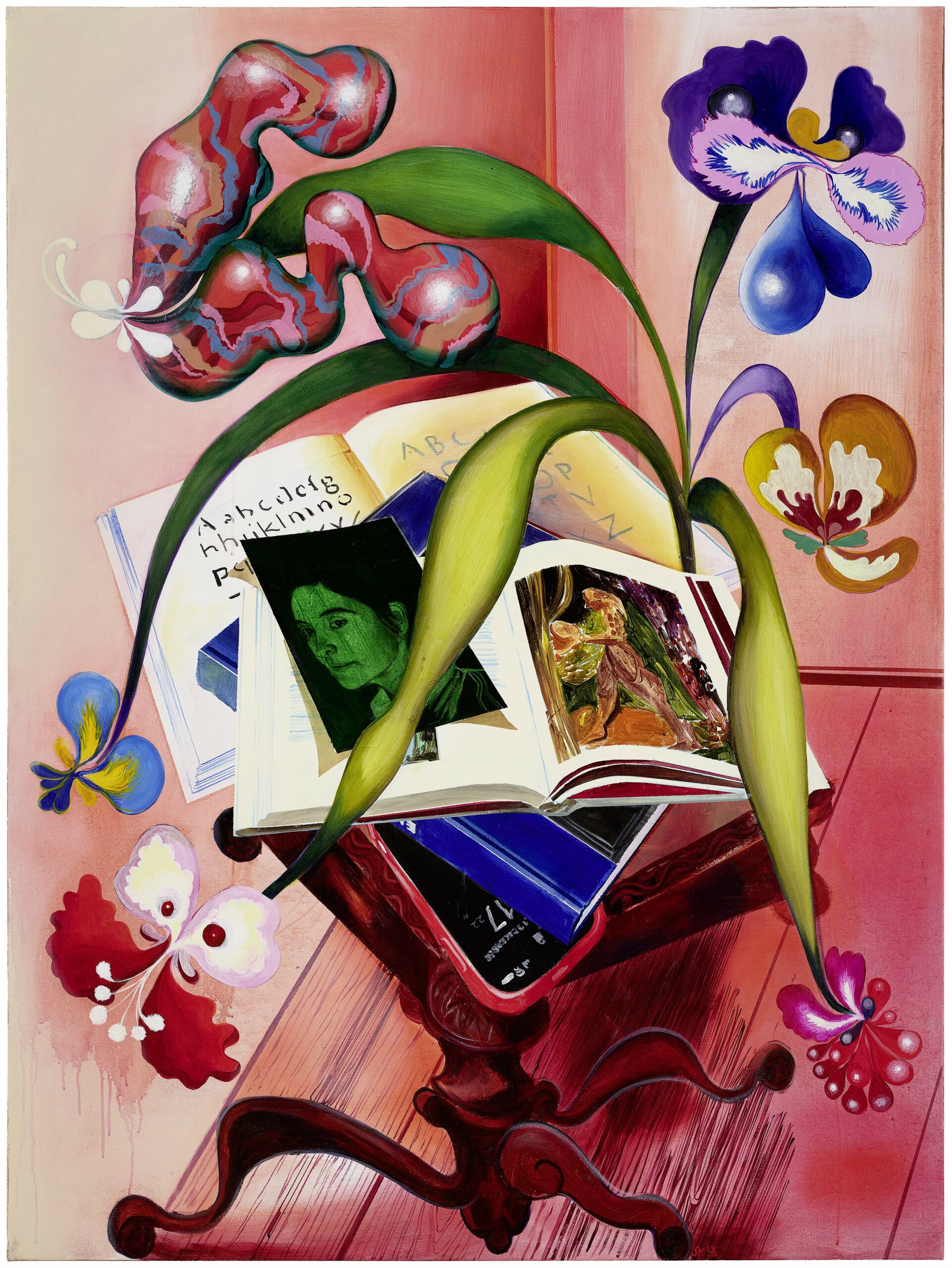

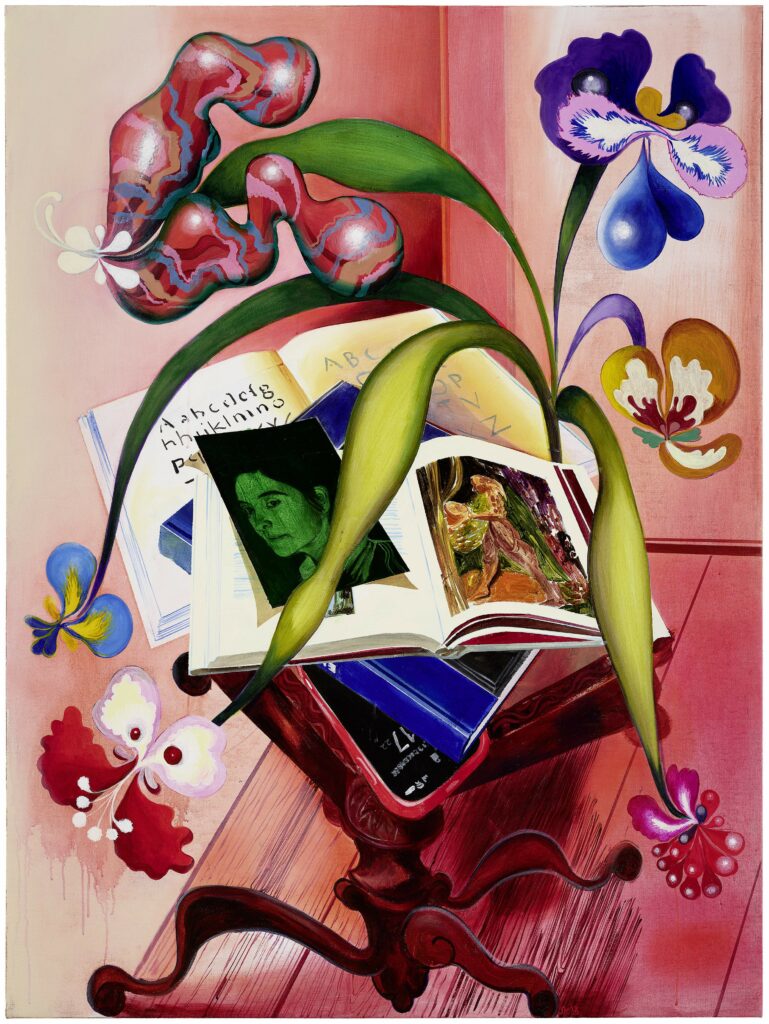

Susanne Kühn|Still life with images and flowers|2023|160x120cm|Acrylic on canvas

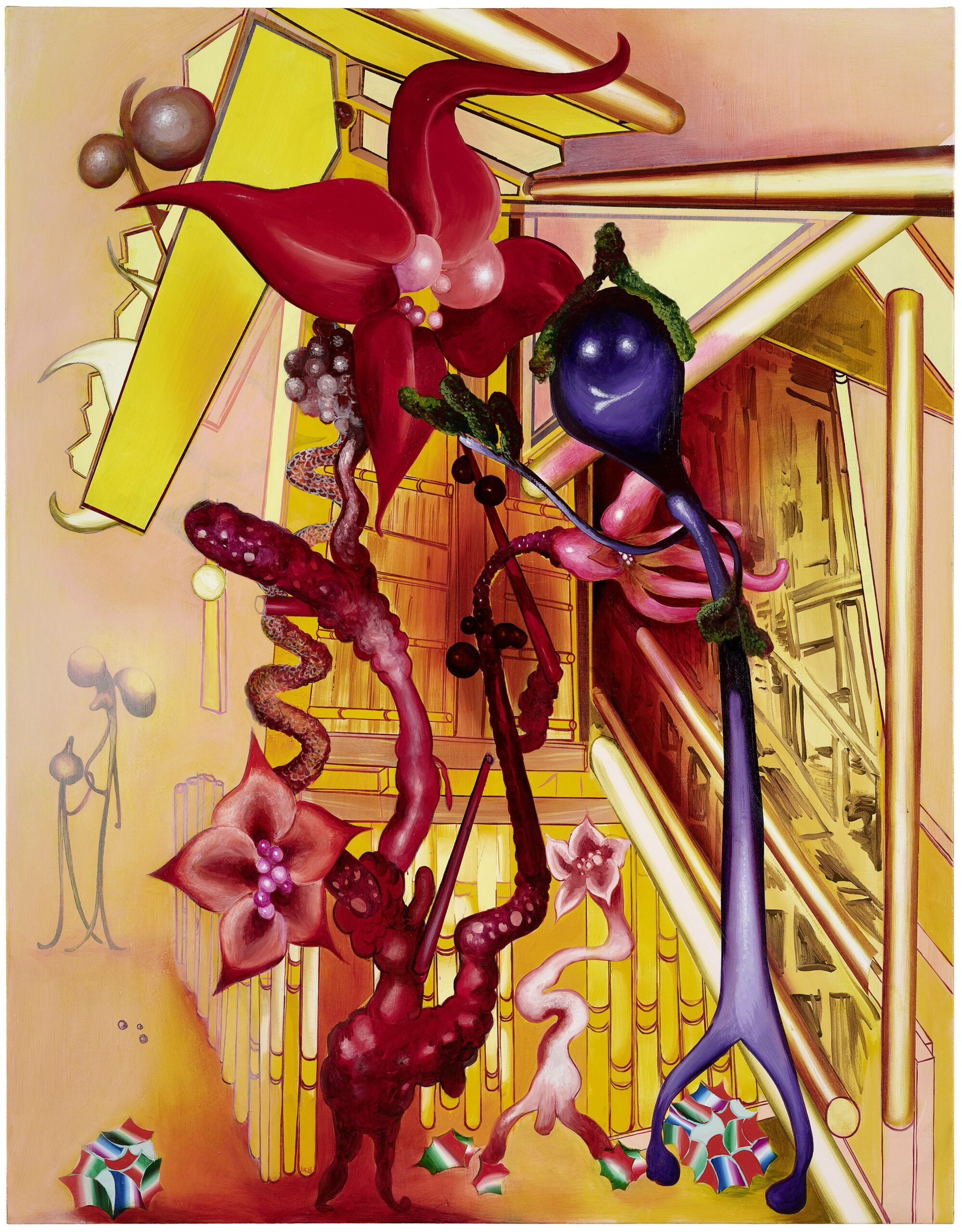

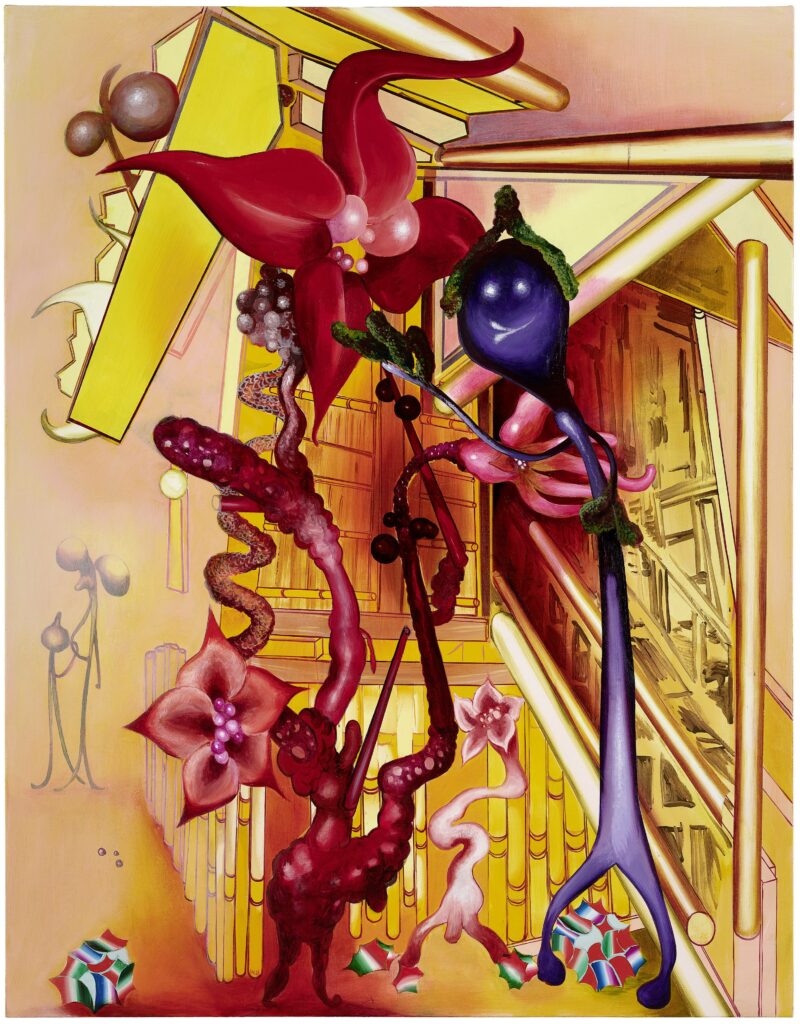

Susanne Kühn|This is the back of my garden|2023| 180x140cm| Acrylic on canvas

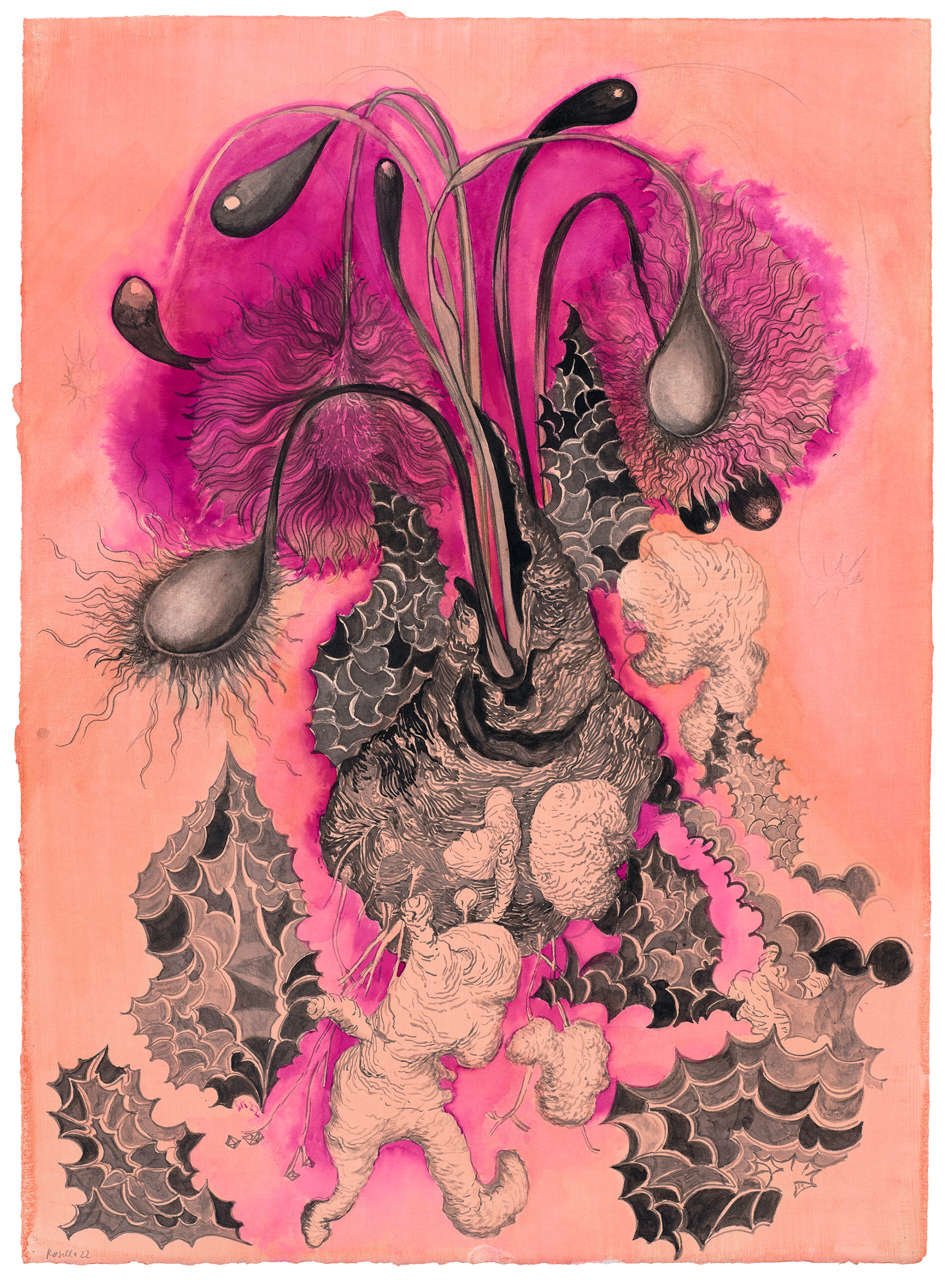

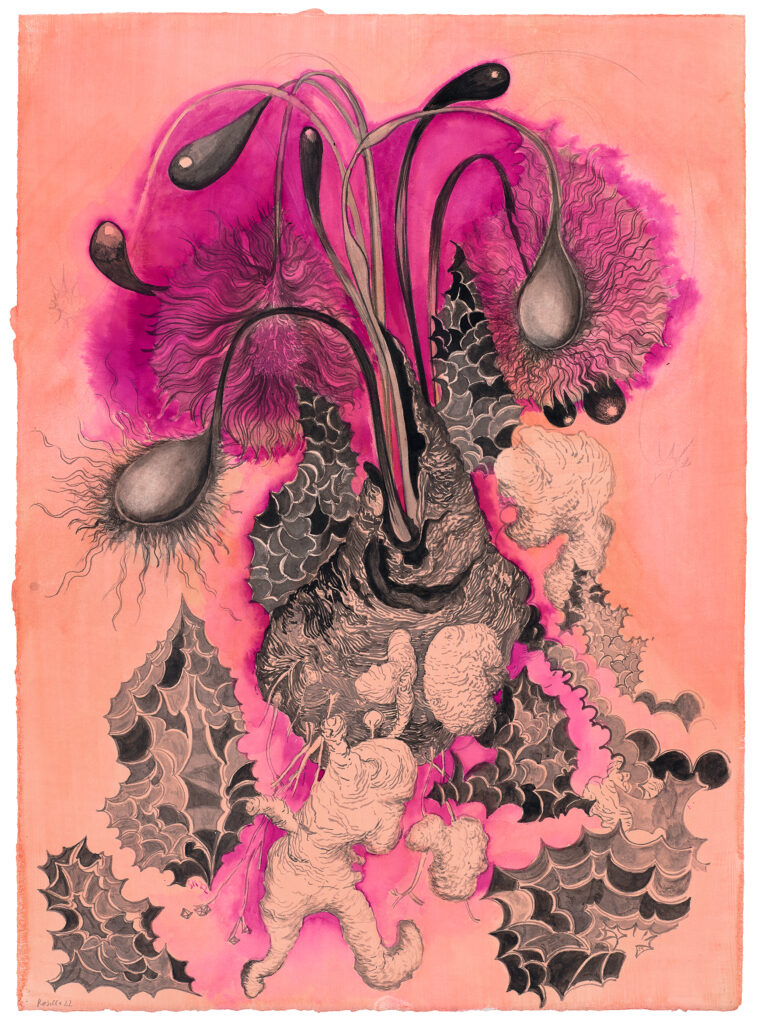

Susanne Kühn|Rosella|2022| 52x38cm| Ink and watercolour on paper, framed

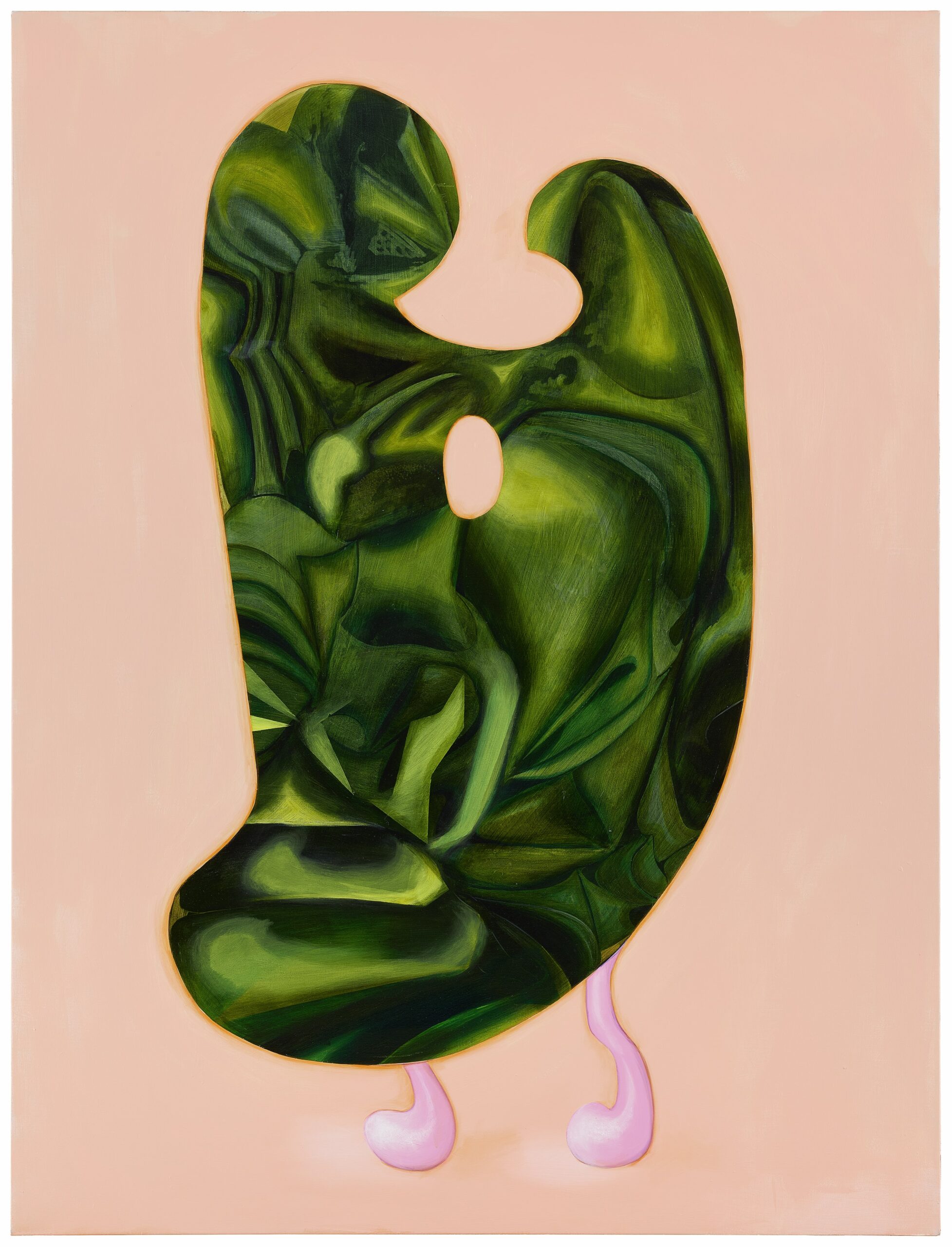

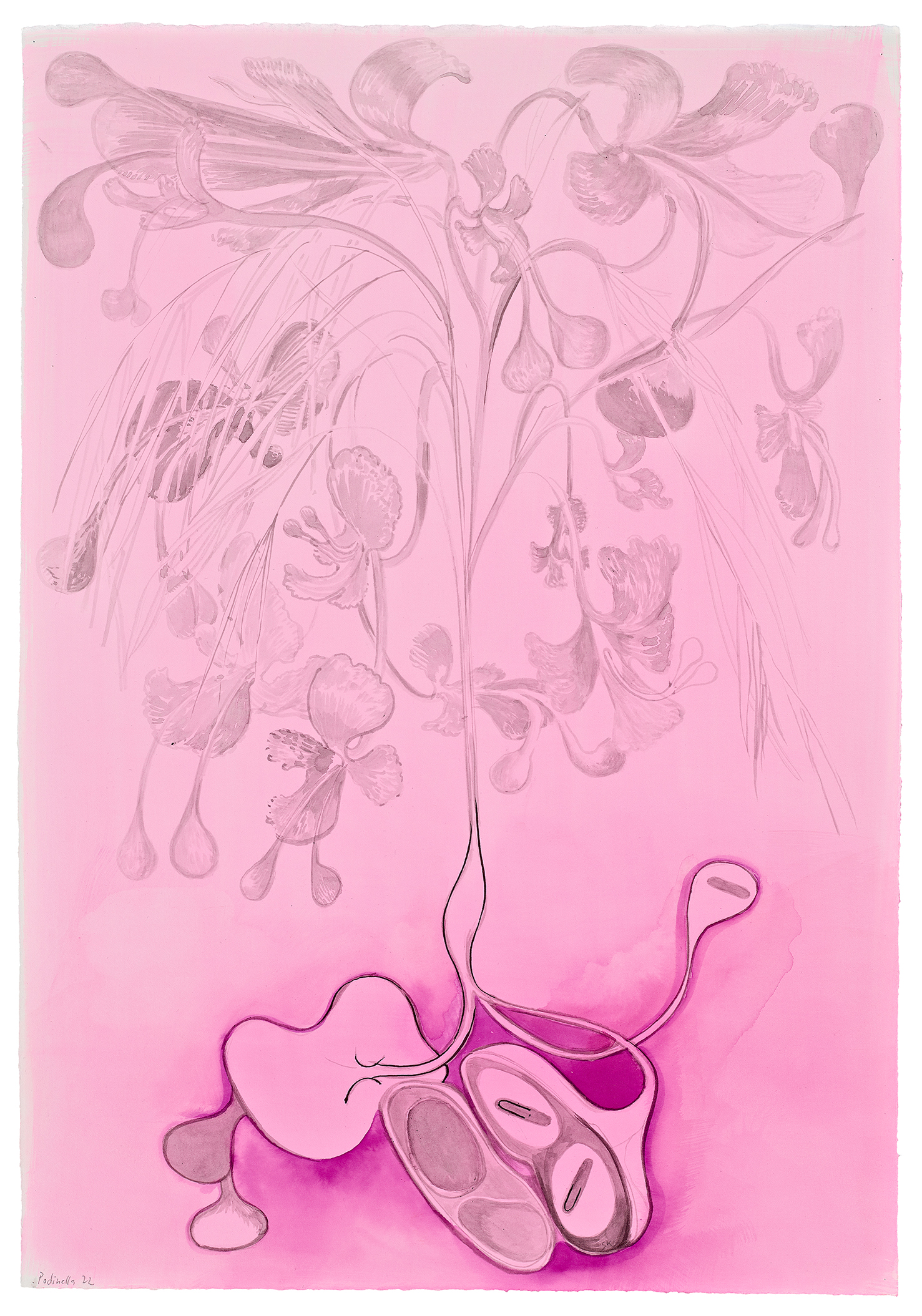

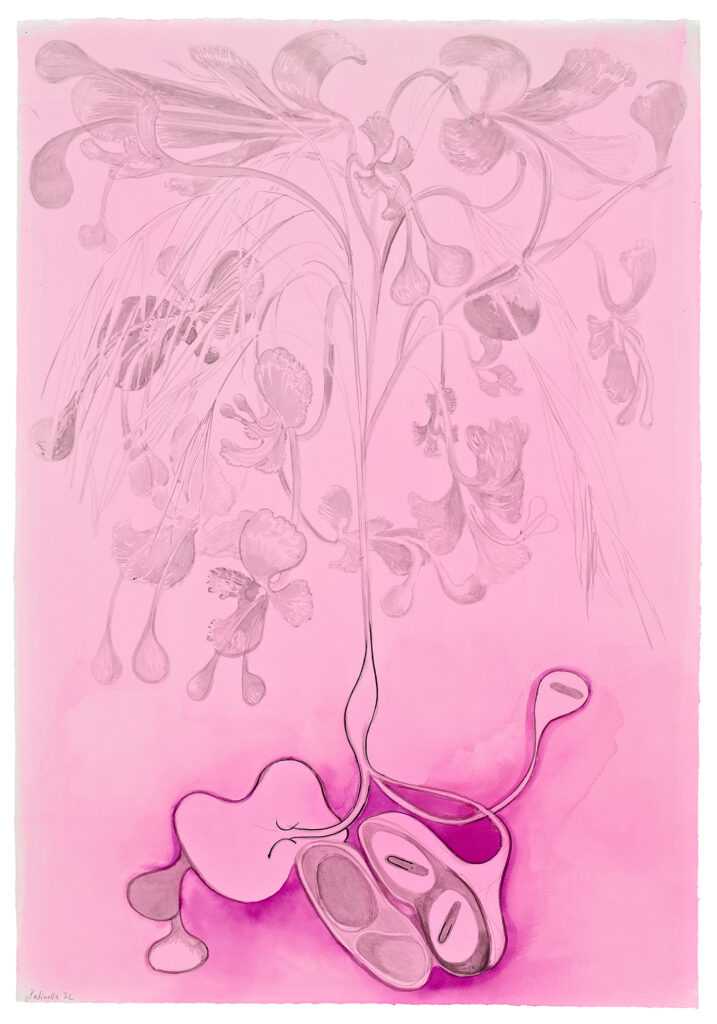

Susanne Kühn|Podipede|2022|51.5×35.5cm|Ink and watercolour on paper, framed

Education

1990-1995 Diploma Degree Program in Painting and Printmaking, Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst Leipzig, Germany

1992 Short-Term Study Grant, DAAD, University College London, UK

1995-1996 Postgraduate Grant, DAAD, School of Visual Arts and Hunter College, New York, USA

2001-2002 Harvard Radcliffe Institute Fellowship, Harvard University, Cambridge, USA

1995-2002 work and studies in New York and Boston, USA

2021 Harvard Radcliffe Summer Fellow, Harvard University, Cambridge USAsince 2015 Professor for Painting, (Chair) Academy of Fine Arts, Nuremberg, Germany

Since 2002 lives and works in Freiburg and Nuremberg, Germany

Selected Solo Exhibitions

2023 Susanne Kühn, GIGMunich, part of Various Others Munich, Lothringer 13 STUDIO

2022 Susanne Kühn, Profliferation – Vasa, Auginella & other Sprouts, Galerie für Gegenwartskunst, E-Werk Freiburg, Germany

2021 Susanne Kühn. Malerei OnSite, Kunstmuseum Celle mit Sammlung Robert Simon, Germany

2021 FLASH – Susanne Kühn, Beck & Eggeling Düsseldorf, Germany

2020 BANK – Inessa Hansch + Susanne Kühn, Augustinermuseum Freiburg, Germany

2019 BOSCH & KÜHN, Gemäldegalerie der Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien, Austria

2019 “PALETTE”, Beck & Eggeling Vienna, Austria

2017 Susanne Kühn, viennacontemporary art fair, Beck & Eggeling, Vienna, Austria

2017 Susanne Kühn, SPAZIERGÄNGE & andere STORIES, MNK im Haus der Graphischen Sammlung, Augustinermuseum Freiburg, Germany

2016 Susanne Kühn, ArtOMI International Arts Center, Ghent, New York, USA

2015 BANK, Galerie Kleindienst Leipzig, Germany

2014 Susanne Kühn – World of Wild Animals, Beck&Eggeling Düsseldorf, Germany

2012 15 Drawings, Sala Uno, Contemporary Arts Center Rome, Italy

2011 Susanne Kühn – GARDEN EDEN, Haunch of Venison, London, UK

2010 Susanne Kühn, Kunstverein Lippe, Germany

2010 Susanne Kühn – Study of Landscape, Robert Goff Gallery, New York, USA

2009 Susanne Kühn, Forum Kunst, Rottweil, Germany

2008 Susanne Kühn, Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, USA

2008 Susanne Kühn, Goff+Rosenthal Berlin, Germany

2007 Susanne Kühn, Kunstverein Freiburg, Germany

2007 New Paintings, Goff+Rosenthal, New York, USA

2007 Drawings, Fred (London) Ltd, Leipzig, Germany

2006 Paintings, Galerie Echolot, Berlin, Germany

2005 Susanne Kühn, Fred (London) Ltd, London, UK

2005 Susanne Kühn, Goff+Rosenthal, New York, USA

2004 Susanne Kühn, Galerie Echolot, Berlin, Germany

2004 Malerei + Zeichnung, Galerie Kleindienst, Leipzig, Germany

2003 Works on Paper, Bill Maynes Gallery, New York, USA

2002 Journey, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, USA

2001 Recent Works, Bill Maynes Gallery, New York, USA

2000 Drawings, Bill Maynes Gallery, New York, USA

2000 Recent Paintings, Samek Art Gallery, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, USA

2000 Drawings, German Consulate House, New York, USA

1999 Paintings, Bill Maynes Gallery, New York, USA

1997 Landscapes, Beck & Eggeling, Leipzig, Germany

Selected Group Exhibitions

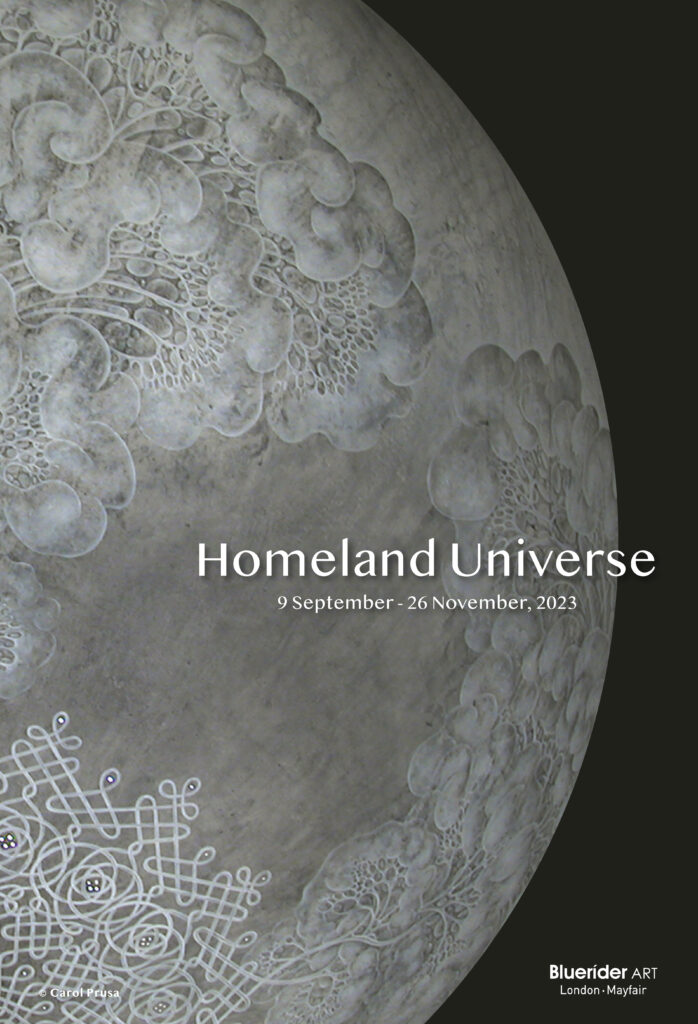

2023 Homeland Universe, Bluerider ART London Mayfair, UK

2023 (Künstler-)Welten, Galerie Ulrich Mueller, Cologne, Germany

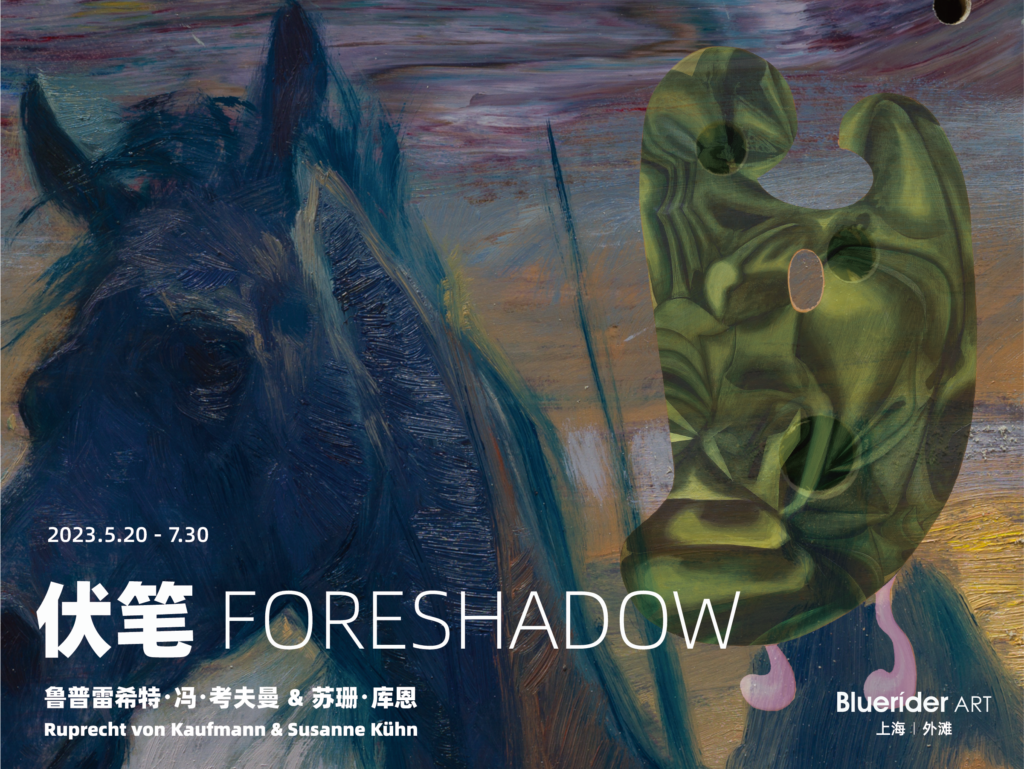

2023 Foreshadow, Bluerider ART Shanghai, Shanghai, China

2023 Kammerspiel: Die Sammlung Gabriele Rauschning, Haus der Graphischen Sammlung – eine Ausstellung des Museums für Neue Kunst, Germany

2023 Wild Grass, Bluerider ART Shanghai, Shanghai, China

2023 Wild Grass, Bluerider ART, Taipei, Taiwan

2022 Autumn, Bluerider ART, Taipei, Taiwan

2021 Freundschaftsspiel, Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg, Germany

2021 PARADE, Beck & Eggeling Düsseldorf, Germany

2021 HousesHomes, Beck & Eggeling Düsseldorf, Germany

2020 Ausgepackt, 125 Jahre Geschichte(n) Museum Natur und Mensch, Freiburg, Germany

2019 Geheimnis der Dinge. Malstücke, Kunsthalle Recklinghausen, Germany

2019 House for a Painting, FRAC Alsace, France

2019 Geheimnis der Dinge. Malstücke, Beck & Eggeling, Düsseldorf, Germany

2019 To Catch a Ghost, Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg, Germany

2018 Gelb macht glücklich – International Fine Art, Düsseldorf + Wien, Germany

2018 Strange Beauty – Beck & Eggeling International Fine Art, Düsseldorf + Wien, Germany

2017 Multiverse: Stories of This World and Beyond, Kemper at the Crossroads, Kansas City, USA

2017 Künstler der Galerie – galerieKleindienst, Leipzig, Germany

2017 Nebukadnezar, Forum Kunst Rottweil, Germany

2016 Den Wald vor lauter Bäumen…, Museum Frieder Burda, , Germany

2016 Ein Baum ist ein Baum ist ein Baum, Beck & Eggeling, Düsseldorf, Germany

2015 Autumn, Twilight, Dwelling among Mountains, Kemper Museum, Kansas City, USA

2015 Die bessere Hälfte – Malerinnen aus Leipzig, Kunsthalle der Sparkasse Leipzig, Germany

2014 Drive the Chance, 100plus, Zürich, Switzerland

2013 Wahlverwandtschaften, Aktuelle Malerei und Zeichnung aus dem Museum Frieder Burda, Museum Franz Gertsch, Burgdorf, Switzerland

2013 Wetterdämmerung – ein Blick zurück, Sammlung Alison und Peter W. Klein, Germany

2013 Inside, Merkur Art Gallery Istanbul, Turkey

2012 Contemporary German Painting: The Future Lasts Forever, Interalia, Seoul, South Korea

2012 Malerei der ungewissen Gegenden, Kunstverein Frankfurt, Germany

2012 The Observer, Haunch of Venison London, UK

2012 Das eigene Kind im Blick. Künstlerkinder von Runge bis Richter, von Dix bis Picasso, Kunsthalle Emden, Germany

2012 salondergegenwart, Hamburg, Germany

2011 The Big Reveal, Kemper Museum, Kansas City, USA

2011 Hello. Goodbye. Die Sammlung, Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg, Germany

2010 Hängung #6, Sammlung Alison and Peter W. Klein, Eberdingen-Nussdorf, Germany

2010 Die Bilder tun was mit mir – Einblicke in die Sammlung Frieder Burda, Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden, Germany

2009 Carte Blanche IX, Museum of Contemporary Art Leipzig, Germany

2008 Future Tense: Reshaping the Landscape, Neuberger Museum of Art Purchase, New York, USA

2008 Böhmen liegt am Meer, Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden, Germany

2007 House Trip, Special Exhibition Art Forum, Berlin, Germany

2007 Neue Malerei. Aus dem Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden, Museum im Prediger, Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany

2006 Inaugural Exhibition, Goff+Rosenthal, Berlin, Germany

2006 Neue Malerei: Erwerbungen 2002-2005, Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden, Germany

2006 Dragon Veins, University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum, Tampa, FA, USA

2005 International Biennale of Contemporary Art, Prague, Czech Republic

2004 EAST International, Norwich Gallery, Norwich, UK

2004 Zweidimensionale 2004, Kunsthalle der Sparkasse Leipzig, Germany

2004 INdiVISIBLE SITlES, Bill Maynes Gallery, New York, USA

2002 Into the Woods, Julie Saul Gallery, New York, USA

2002 Works on Paper, Bill Maynes Gallery, New York, USA

2002 Curious Terrain, Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York, USA

2002 Postmodern Pastoral, Judy Ann Goldman Fine Art, Boston, USA

2001 Wet!, Luise Ross Gallery, New York, USA

2001 Chelsea Rising, Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans, USA

2001 Wonderland, Massachusetts College of Art, Boston, USA

2000 Bildwechsel, Kunstverein Freunde Aktueller Kunst, Städtisches Museum Zwickau, Germany

2000 Art on Paper Annual, Weatherspoon Art Museum, University of North Carolina, Greensboro, N. C., USA

Collections

Busch-Reisinger Museum Collection / Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA, USA

University of Colorado Art Museum, Boulder, CO, USA

Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, MO, USA

Knoxville Museum of Art, Knoxville, TN, USA

Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

FRAC Alsace, France

Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden, Germany

Kunstmuseum Celle mit Sammlung Robert Simon, Celle, Germany

Sammlung der Deutschen Bundesbank, Germany

Sammlung Alison and Peter W. Klein, Germany

Museum für Neue Kunst, Freiburg, Germany

Sammlung Sachsen Bank, Germany

Sammlung der Sparkasse Leipzig, Germany

UBS Art Collection, Switzerland

The Graphic Collection of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, Austria

Picture Gallery of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, Austria

Zabludowicz Art Trust