Author: Sylvia Dominique Volz

Sylvia Dominique Volz is a renowned German art consultant, editor, and curator who holds a Ph.D. in art history from Heidelberg University. She provides contemporary art collection consulting services for private collectors and corporate institutions. Additionally, she has served as the editor-in-chief for the prestigious contemporary art private collection guide, "The BMW Art Guide," on multiple occasions.

IMAGE FORMATION AS A (DISTORTING) MIRROR OF REALITY

IMAGE FORMATION AS A (DISTORTING) MIRROR OF REALITY

By Dr. Sylvia Dominique Volz

Human existence in all its complexities—the efforts to control others through mani- pulation, a primal instinctive behavior that does not differentiate between rational and irrational—is the central theme of Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s work. Here, man is seen as a threat to nature and his own species, characterized by the neediness, vulnerability, and finitude of his earthly existence.

Deep and mysterious, the paintings draw viewers in, leaving them spellbound. We are challenged by the diversity and complexity of their encrypted and contradictory nature. They unleash a variety of associations within us, thereby generating a mix of emotions that, as the artist notes, corresponds most closely to our own experiences in life: from unease, dismay, and feeling threatened, to joy, love, and hope—at times all within a single image. We attempt to engage in, decode, and make sense of things, finally to conclude that what takes place occurs less before our eyes than within ourselves. Are the protagonists ultimately a reflection of ourselves? Whose role are we taking on? Are we an active part of the scenery unfolding before and within us?

因此,這些成為與身為觀者的我們產生共鳴與互動的圖像。在社交媒體的世代,這對我們來說似乎很自然。Ruprecht von Kaufmann本人著迷地觀察著所謂的用戶如何利用敘述來塑造他們自己的個人特質。這些即是被操控的主觀真相,因為有些圖像的設計確實旨在向外傳達意念。觀看的時候,腦中所感知到的是情感上觸動觀者的一幅美麗(被美化的)肖像,因為它產生了一種匱乏感且喚醒了深沉的隱性需求。簡而言之,Ruprecht von Kaufmann藝術地捕捉了現實與虛構之間的差異。在他一幅描繪一位背對著的女性正在脫去她比例勻稱的皮膚的畫作中,顯現出來的是一位瘦到近乎消失的纖弱人形,而且她與即將要被拋掉的皮膚形象幾乎沒有任何共同之處(Take off Your Skin[譯:脫去你的外皮])。

Slipping into various roles or manipulated images of oneself, however, is not only a phenomenon of modern times, but runs more or less throughout the entire history of mankind and art; humans have forever been concerned with whom they would like to be and in what role they would like to be seen. Even in ancient times, the concept of the person or persona was commonly used, among other things, as a term for the actor’s mask and the role one plays in acting or in life. Throughout the centuries, portraits, whether in word or image, have frequently been choreographed down to the very last detail: just think of rulers who flaunted their social status, their education, and supposed noble character traits by means of elaborately deployed symbolism, thus constructing their image in the truest sense of the word.

Ruprecht von Kaufmann對於在真實與虛構世界之間搖擺不定的形象特別感興趣;因此,對於美國創作歌手 Tom Waits所寫的歌詞成為他的靈感來源之一也就不足以為奇了—這位音樂家本身就是一位難以自我受限的創作家,他以在歌詞中呈現各種虛構人物並營造出一種不一致且複雜的氛圍為特色,如同我們在Ruprecht von Kaufmann的作品中所感受到的那般。畫作中的主角以不同的形式出現,有些帶有強烈的操控或威嚇感,有些則是有需求或脆弱的感覺。我們會遇上一些奇特的混合型生物,例如半人馬這種怪物睡在床上,然後一位裸體的女性信任地依偎在牠身上(Monster [譯:怪物]),或者是一個完全被包裏在像麻布袋中的生物蹣跚地在房間內移動著(Die Gefährten [譯:夥伴們])。他們的真正身份其實並未向我們揭露,尤其因為他們的頭被轉向、被扭曲得面目全非、或者被遺漏了。由於我們總是試圖閱讀與識別臉部特色以定位我們與對方之間的關係,這樣的呈現更是讓人感到困惑。

When observing the at times complex pictorial spaces, dominated predominantly by people and their actions, it would be remiss of us to assert that Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s work lacks narration. In fact, this is not the artist’s intention: in his view, narrative is a fundamental means for touching people emotionally. He is therefore reluctant to approach painting from a purely formal and intellectual level. This is indeed worth noting, since this pits his images against current negative attitudes in the art context towards narrative in painting. Moreover, this stance is interesting since Ruprecht von Kaufmann comes across as a highly intellectual individual whose images attest not least to an intensive examination of history, politics, art history, literature, ancient mythology, and music.

Nevertheless, what unfolds before the eye of the viewer is not to be regarded in any way as a fully developed story. Rather, they are fragments, or more precisely narrative strands that are only intimated but not resolved. At first, the artist evokes narrative using tangible means that correspond to our established modes of seeing and our subjective horizon of experience, thus offering a seemingly easy way into the imagery. This applies equally to images of circus scenes, mountain landscapes, or autobiographical themes such as childhood and the transition to adulthood—to name just a few.

隨後,我們便會對自我假定的見解產生懷疑。Ruprecht von Kaufmann便向我們展示各種難以理解的細節,像是一匹有兩個後驅的馬(Pastorale [譯:牧人]),一個不合建構邏輯的空間結構,或者甚至是圖像中的間隙;當獨自觀賞時,不只無助於釐清情境,反而延伸出更多的疑問。觀眾更是被鼓勵自由發揮幻想、解決矛盾之處、並化不合邏輯為合理。Ruprecht von Kaufmann表示:「圖像實際上只在觀眾自己的腦海裡出現。」敘事片段因此扮演著藝術家為我們搭建的橋樑角色,而他本人則在基地周遭徘徊,並且在鼓勵我們持續前進之後。

Another aspect that runs counter to the purely narrative nature of Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s work is the absence of a fully fleshed-out concept before setting to work. He begins with a vague idea that he allows to guide him. Only in the course of the painting process does it become clear what the painting is all about.

The artist himself likes to refer to the principle of “serendipity“, meaning observing something by chance you weren’t looking for, but which turns out to be a new and surprising discovery. This very principle is reflected in the creative artistic process of Ruprecht von Kaufmann, who freely proceeds from one idea to the next without an overarching concept in mind. A coincidental connection crops up here or there, or a change of direction is undertaken, at times making for unexpected discoveries. Bored-out holes or the application of collage-like elements can develop as a result, breaking up the surface and setting it in motion.

畫作的標題通常也是在創作過程中才確定。如果,以例外的情況來說,假設作品主題在一開始就設定好,它將會是參考啟發藝術家靈感的一句名言、聲明、或者歌名—例如Babe I’m Gonna Leave You (譯:寶貝,我要離開你了)或You never know (譯:你從不知道)。然而,隨後在圖像表面上所形成的東西將會與純粹的示意圖相去甚遠。

整體來說,這些標題在某種程度上常常具有令人驚訝的諷刺意味—例如,在My Thoughts Grow so Large on Me (2016) (譯:思想在我身上變得如此之大)的作品中,畫作主角的頭頂上卻幾乎只剩下抹刀塗抹的殘留漆料;這讓人聯想到的反而是廢物而非其他情操更高尚的活動。或者例如Der Entertainer (譯:表演者)中,主角的頭部僅以一縷輕煙呈現。又或者當Rude Awakening (譯:後悔莫及)裡面熟睡的情侶從向下傾斜的床上倒掛下來時,彷彿真的被丟棄了一樣。不證自明地,一個幽默的標題能夠相對化作品的陰鬱與沉重;就如同當那隻像是地獄獵犬一樣的生物正在撕毀另一隻野獸時,畫作的標題卻是Sorglos (譯:無憂無慮)。如此這般地產生吸引人的對比性,使人聯想起Martin Scorsese或Quentin Tarantino所執導的電影中,殘忍行徑的場景通常會伴隨著歡快的配樂。

Ruprecht von Kaufmann的作畫手法玩弄著我們典型的感知方式,使觀者的雙眼不停移動著。我們的雙眼找尋支點,然後在找到了之後再次分心;接著可能再次返回稍早停佇過的點,然後再離開朝向其他方向。物理上來說,在畫作前的空間上下移動著似乎仍然無法提供足夠的說明。可能的例子是In the House (譯:房子裡)這個作品,觀者在作品中的視線移動—如電影運鏡那般—由左至右穿過一個屋子。整個過程經歷了六個位置,從樓梯井開始,觀眾被引導至越來越深的內部,直到突然發現自己身處屋外。

對Ruprecht von Kaufmann而言,重要的是視角的變化;這個概念在這裡特別容易理解,因為藝術家分別在鳥瞰方式與採用較觀者視線稍高一些的視角之間交替變化著,一次從左斜對角,然後下個瞬間便改由右斜對角開始。眼神的閃爍掃視為觀者帶來一種不安全感,甚至是一種令人壓抑的感覺—特別是當藝術家從背後的角度向我們展示一位雜耍演員,站在令人眼花繚亂的高空鞦韆上俯視著馬戲團的地板,那是最專注且神經緊繃的時刻。那感覺幾乎像是地板正在從我們的腳下被抽出—好像我們才是負責要像雜耍演員那般地盪那個鞦韆並在空中旋轉(Der Trapezakt (譯:高空鞦韆)。在State of the Art (譯:先進前衛的)這種多重元素作品中,其繪畫的視角與繪板的形狀讓我們產生更多的問題,像是一幅可折疊的祭壇畫,卻有著不對稱的外形,讓人永遠無法如願地使其發揮作用。

While Ruprecht von Kaufmann has been creating his works in oil on canvas for many years, 2014 marked a turning point when he decided to use linoleum as painting surface and has since then been doing so consistently. The multi-part portrait series Die Zuschauer [The Spectators] (2014) serves as an example of this switch: peering out at us from fifty-five DIN A4-sized panels are various characters or “personalities”; a variety of portraiture forms are employed here, from the head shot to the bust and the head-and- shoulder portrait, to the half- length figure. As you move in, you notice that the portraits almost seemingly dissolve at times. Eyes are drilled out, facial features are only indicated vaguely or in outline or even painted over using a spatula, while scraping threatens to destroy others. Also conspicuous is the assortment of colors we encounter here; the palette ranges from more reserved gray and blue tones to shrill orange, yellow, or bright magenta. Such color experimentation, however, is not only related to the portraits themselves, but also seems to take its cues from the background hues. At times, strange color sprinkles from the linoleum remain evident.

Here we find ourselves at the core source of the color: it is actually the linoleum itself that literally sets the tone for the painting. Ruprecht von Kaufmann came across the material—a mixture of linseed oil and cork—by chance. While doing construction work on his own home he discovered variously colored linoleum panels that soon aroused his artistic curiosity. The material, produced in a variety of shades, promised to become an experimental field of almost unlimited possibilities.

他隨後訂製了一個40 x 30 公分的混色板,並大量地測試油畫顏料在畫板表面的表現方式;與一般畫布不同的是,因為其材料特性的關係,作畫時並不需要塗底漆。Ruprecht von Kaufmann也注意到,通常空白的白色補片在畫布上總是看起來像「未完成品」,但油氈板的基材在需要時,可以簡單地將其「單獨放置」(Schmelzwasser (譯:融水)。因此,他讓自己被各種材料色彩引導著,以各自的色調活力作為參考點。因此,一個有趣的過程、一種對話隨之開啟,因為每一個圖像與每種色調都將產生新的想法:當紫羅蘭色遇上黃色、黃色碰上藍色、橙色遇見灰綠色、而洋紅色撞入黑色。更具實驗性的是這些畫作,壁紙或地板上被覆蓋滿五顏六色的圖像,人物則像是身在叢林中那般被框住,例如Monster (譯:怪物)、Auferstehung (譯:復甦)、Der Zeuge (譯:目擊者)、或You Never Know (譯:你從不知道)。潛在的色彩組合似乎無窮無盡。

The newly discovered material matched Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s long- cherished desire to use color more powerfully as an individual element, in contrast to earlier works, which are characterized by a rather homogenous, muted tonality. The images thus achieve an obvious presence, but still remain subtle enough that they avoid becoming too conspicuous.

從畫布切換到油氈時,Ruprecht von Kaufmann還因此能實現另一個願望,即賦予畫作中的各個元素更多的圖像品質,從而將它們與畫作中的其他區域切割開來。如果我們看諸如Schmelzwasser (譯:融水)這一類的作品,畫中的主角看起來既精緻又含蓄,如同畫在紙上那般。藝術家尤其喜歡強調筆刷與漆料在油氈上極佳的流動性,非常適合書法手法。他幽默地表示,圖像背景可以「像一幅拙劣的油畫那般輕鬆地塗抹」,將顏色保留在最上方,覆蓋著下方的漆料。

Last but not least, the material, he explains further, is characterized by a certain resistance to pressure compared to canvas. This is of particular significance when Ruprecht von Kaufmann occasionally applies paint to individual parts of the canvas with a spatula.

It goes without saying that the formal changes mentioned also have an effect on content. Both graphical elements and individual areas left unpainted in the background at times lend the pictures a degree of abstraction that enters into an exciting dialogue with the rest of the painting. If one looks at the last works Ruprecht von Kaufmann created on canvas prior to switching to linoleum—the series with circus scenes—a tendency towards greater abstraction can already be seen in them. In contrast to earlier paintings, the background here is no longer as detailed, but is on closer inspection more reminiscent of sketched-out, geometric forms.

Ultimately this development leads to the linoleum works, in which individual image layers are distinguished from one another even more clearly than before—by graphical elements, by sections that dissolve into carved-out marks, and by fragments of foil applied in a collage-like manner. All of these contribute to the increasingly sculptural quality of the images—almost as if wanting to question the classical art historical distinction between genres of painting, sculpture, and drawing.

內容層面上,各個圖層亦同樣表現著不同的含義:舉例來說,Schmelzwasser (譯:融水)前景出現的四個人像是直接塗在「原始」的油氈板上,代表著四個世代的藝術家族。由左到右,坐著的是Ruprecht von Kaufmann的曾祖父,站在一旁的是他的祖父,接著是在畫作斜對角的父親,以及最後是藝術家本人以幾乎水平的方式呈現在作品中。身穿軍服的人物以順時針的方向排列,就像是在暗指時間因素且一切因此頃刻即逝。

It is interesting to note that Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s figure is only rendered graphically in outline, therefore escaping our perception, so to speak, while his forebears enjoy a greater physical presence. It seems as if the artist is alluding to the fact that his life can still be “filled out.” Rising up in the background behind the figures is an impressive mountain range, whose mid-section, now a melting glacier, has been removed and broken up by marks gouged out of the image ground.

從他們的穿著來看,圖中的人物不只是家人,而且是四代的高山部隊。完成山地救援兵役的Ruprecht von Kaufmann強調那段時間培養了他對大自然的熱愛。他對大自然有永久的責任感,以及對所有與此相關或者其未來所有世代有責任,這尤其體現在他整個作品反覆出現的山地主題之中。這裡是嚮往與紀念相互結合之地—尤其是後者,當藝術家想表達冰川融化的威脅時,不只在上述提及的Schmelzwasser (譯:融水)作品,而且也出現在Jannu 、Der Fjord (譯:峽灣)、Natur (譯:自然)、以及Landschaft (譯:風景)這些作品之中。特別是當前關於氣候行動的辯論與為氣候罷課運動正盛行的情況下,這些圖像比以往任何時候都更引人注目。

It is clear that Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s paintings should never be thought of solely in a subjective-autobiographical context, but that, above and beyond this, they must also be considered from a global, universally valid perspective. These are deeply personal images that we are only able to access via our own emotionality. In them we search for, recog- nize, question what is presented and develop it further. The power and powerlessness of the protagonists reflect and move us, above all because they show us how mutable man is, in both a negative as well as positive sense. The step from perpetrator to victim—and vice versa—is often less than a stone’s throw away from each other, and in this peculiar entangling we have a mutual effect on one another. In Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s painting, man’s facets are as varied and diverse as the range of tonalities between black and white. As viewers, we are challenged to enter into a dialogue in order to come to this realization in a dynamically variable manner.

IMAGE FORMATION AS A (DISTORTING) MIRROR OF REALITY

Dr. Sylvia Dominique Volz

Human existence in all its complexities—the efforts to control others through mani- pulation, a primal instinctive behavior that does not differentiate between rational and irrational—is the central theme of Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s work. Here, man is seen as a threat to nature and his own species, characterized by the neediness, vulnerability, and finitude of his earthly existence.

Deep and mysterious, the paintings draw viewers in, leaving them spellbound. We are challenged by the diversity and complexity of their encrypted and contradictory nature. They unleash a variety of associations within us, thereby generating a mix of emotions that, as the artist notes, corresponds most closely to our own experiences in life: from unease, dismay, and feeling threatened, to joy, love, and hope—at times all within a single image. We attempt to engage in, decode, and make sense of things, finally to conclude that what takes place occurs less before our eyes than within ourselves. Are the protagonists ultimately a reflection of ourselves? Whose role are we taking on? Are we an active part of the scenery unfolding before and within us?

These are therefore images we resonate and interact with as viewers. In the age of social media, this seems almost natural to us. Ruprecht von Kaufmann himself observes with fascination how so-called users employ narratives to form their own personal identities. These are the manipulated, subjective truths that certain images are designed to outwardly convey. What sticks in the mind when looking is an enviably beautiful (beautified) portrait that touches the viewer emotionally insofar as it creates a sense of lacking and awakens deeply hidden needs. In a nutshell, Ruprecht von Kaufmann artistically captures this discrepancy between reality and fiction in his painting of a female figure from behind ridding herself of her amply proportioned skin. Seen emerging is an almost vanishingly thin, slight person who seemingly shares nothing in common with the one about to be left behind (Take off Your Skin).

Slipping into various roles or manipulated images of oneself, however, is not only a phenomenon of modern times, but runs more or less throughout the entire history of mankind and art; humans have forever been concerned with whom they would like to be and in what role they would like to be seen. Even in ancient times, the concept of the person or persona was commonly used, among other things, as a term for the actor’s mask and the role one plays in acting or in life. Throughout the centuries, portraits, whether in word or image, have frequently been choreographed down to the very last detail: just think of rulers who flaunted their social status, their education, and supposed noble character traits by means of elaborately deployed symbolism, thus constructing their image in the truest sense of the word.

Ruprecht von Kaufmann is particularly interested in such figures who oscillate between worlds, between truth and fiction, and it is hardly surprising that the lyrics of US singer-songwriter Tom Waits serve as one of his sources of inspiration—a musician who is himself hard to pin down, who takes on the identities of various invented figures in his songs and creates the kind of contradictory and complex atmosphere that we encounter in Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s pictures. The painter’s protagonists appear in various guises, some powerfully manipulative or menacing, others needy and vulnerable. We encounter strange hybrid creatures, such as a centaur—half-human, half-horse—asleep in bed, a nude female figure trustingly cuddled up against it (Monster), or a being completely ensconced in a sack-like fabric moving somewhat awkwardly around the room (Die Gefährten [The Companions]). Their true identity remains literally hidden from us, not least because their heads are turned away, are distorted beyond recognition, or even omitted. This is particularly bewildering in view of the fact that we always seek to read and recognize facial features, to position ourselves in relation to others.

When observing the at times complex pictorial spaces, dominated predominantly by people and their actions, it would be remiss of us to assert that Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s work lacks narration. In fact, this is not the artist’s intention: in his view, narrative is a fundamental means for touching people emotionally. He is therefore reluctant to approach painting from a purely formal and intellectual level. This is indeed worth noting, since this pits his images against current negative attitudes in the art context towards narrative in painting. Moreover, this stance is interesting since Ruprecht von Kaufmann comes across as a highly intellectual individual whose images attest not least to an intensive examination of history, politics, art history, literature, ancient mythology, and music.

Nevertheless, what unfolds before the eye of the viewer is not to be regarded in any way as a fully developed story. Rather, they are fragments, or more precisely narrative strands that are only intimated but not resolved. At first, the artist evokes narrative using tangible means that correspond to our established modes of seeing and our subjective horizon of experience, thus offering a seemingly easy way into the imagery. This applies equally to images of circus scenes, mountain landscapes, or autobiographical themes such as childhood and the transition to adulthood—to name just a few.

Subsequently then, our presumed insights are themselves called into question. Ruprecht von Kaufmann thus confronts us with all sorts of incomprehensible details, such as a horse with two hindquarters (Pastorale [Pastoral]), an illogically constructed spatial structure, or even gaps in the image, which, viewed in isolation, raise more questions than contribute to clarifying the scene. The viewer is specifically encouraged to give his fantasy free rein, to resolve what is at odds, and to convert the illogical into the logical. “The image,“ says Ruprecht von Kaufmann, “only actually comes into being within viewers themselves.” Narrative fragments thus serve as a bridge the artist constructs for us, while he himself lingers around its base and retreats after encouraging us to continue onward.

Another aspect that runs counter to the purely narrative nature of Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s work is the absence of a fully fleshed-out concept before setting to work. He begins with a vague idea that he allows to guide him. Only in the course of the painting process does it become clear what the painting is all about.

The artist himself likes to refer to the principle of “serendipity“, meaning observing something by chance you weren’t looking for, but which turns out to be a new and surprising discovery. This very principle is reflected in the creative artistic process of Ruprecht von Kaufmann, who freely proceeds from one idea to the next without an overarching concept in mind. A coincidental connection crops up here or there, or a change of direction is undertaken, at times making for unexpected discoveries. Bored-out holes or the application of collage-like elements can develop as a result, breaking up the surface and setting it in motion.

Titles for the paintings are also typically only worked out in the course of the creative process. If, as an exception to the rule, the title is decided upon beforehand, it will reference a sentence, a statement, or a song title that has inspired the artist—such as Babe I’m Gonna Leave You or You never know. But what takes shape then on the image ground is a distant cry from pure illustration.

In general, the titles are in a certain way often surprisingly ironic—when, for instance, there is almost nothing more left of the top of the head of the person portrayed in My Thoughts Grow so Large on Me (2016) than spatula-applied paint remnants, which are more reminiscent of refuse than higher-minded activity. Or Der Entertainer, whose head consists solely of a plume of smoke. Or when the sleeping couple in Rude Awakening slides upside down off the downward sloping bed, as if being literally disposed of. It goes without saying that a humorous title can relativize the gloom and heaviness of the image theme when a hound-from-hell-like creature tears away at another beast and is simply titled Sorglos [Carefree] A riveting contrast emerges, reminiscent of films by Martin Scorsese or Quentin Tarantino, where a scene marked by brutality is often accompanied by cheery music.

Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s manner of playing with our typical modes of perception in his paintings keeps the eye of beholder constantly in motion. It seeks out a pivot point, finds it, is distracted again, then potentially returns to the earlier point and drifts off from there in another direction. Physically the moving up and down in the space in front of the painting also does not seem to provide sufficient clarification. Potentially paradigmatic of this is the work In the House , in which the viewer moves—reminiscent of a film sequence—from left to right through a house. A total of six locations are traversed; beginning with the stairwell, the viewer is led deeper and deeper into the interior until suddenly finding himself outside the house.

Significant for Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s work is the variation in perspective that is particularly easy to comprehend here, given the artist’s alternating between a bird’s-eye view and an only slightly elevated observer’s point of view, once diagonally from the left, and then, in the next instant, diagonally from the right. The darting of the eye creates in viewers a sense of insecurity, even an oppressive feeling—specifically when the artist shows us an acrobat from behind standing on a swing at a dizzying height looking down at the floor of the circus ring, in a moment of maximum concentration and tension. It almost feels as if the floor is being pulled out from under our feet—as if it were up to us to swing the swing and whirl through the air like an aerial acrobat (Der Trapezakt [Trapeze Act]). The visual angle of the painting but also the very shape of the painted panels raise questions when a multi-element work like State of the Art , reminiscent of a foldable altarpiece, has an asymmetrical outer shape that would never allow it to function as such.

While Ruprecht von Kaufmann has been creating his works in oil on canvas for many years, 2014 marked a turning point when he decided to use linoleum as painting surface and has since then been doing so consistently. The multi-part portrait series Die Zuschauer [The Spectators] (2014) serves as an example of this switch: peering out at us from fifty-five DIN A4-sized panels are various characters or “personalities”; a variety of portraiture forms are employed here, from the head shot to the bust and the head-and- shoulder portrait, to the half- length figure. As you move in, you notice that the portraits almost seemingly dissolve at times. Eyes are drilled out, facial features are only indicated vaguely or in outline or even painted over using a spatula, while scraping threatens to destroy others. Also conspicuous is the assortment of colors we encounter here; the palette ranges from more reserved gray and blue tones to shrill orange, yellow, or bright magenta. Such color experimentation, however, is not only related to the portraits themselves, but also seems to take its cues from the background hues. At times, strange color sprinkles from the linoleum remain evident.

Here we find ourselves at the core source of the color: it is actually the linoleum itself that literally sets the tone for the painting. Ruprecht von Kaufmann came across the material—a mixture of linseed oil and cork—by chance. While doing construction work on his own home he discovered variously colored linoleum panels that soon aroused his artistic curiosity. The material, produced in a variety of shades, promised to become an experimental field of almost unlimited possibilities.

He subsequently ordered a colorful potpourri of 40 x 30 cm panels and experimented extensively with the way the oil paint behaves on the surface of the ground, which, unlike canvas, does not need to be primed due to its material properties. Ruprecht von Kaufmann noticed that while a blank white patch on canvas always looks “unfinished,” the substrate of a linoleum panel can simply be “left alone” when needed [Schmelzwasser [Meltwater]. Accordingly, he allowed himself to be guided by the material’s various colors, working with the vibrancy of the respective hue as a reference point. A playful process, a dialogue was set in motion, because each image, each color, gave birth to a new idea: violet meets yellow, yellow encounters blue, orange comes across gray-green, magenta runs up against black. Even more experimental are the paintings, in which wallpaper or floors are covered with colorful patterns and the figures framed as if in a jungle, such as in Monster , Auferstehung [Resurrection], Der Zeuge [The Witness], or You Never Know . The potential color combinations seem virtually inexhaustible.

The newly discovered material matched Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s long- cherished desire to use color more powerfully as an individual element, in contrast to earlier works, which are characterized by a rather homogenous, muted tonality. The images thus achieve an obvious presence, but still remain subtle enough that they avoid becoming too conspicuous.

In switching from canvas to linoleum, Ruprecht von Kaufmann was also able to fulfill another wish to give individual elements in the image a more graphical quality, thus setting them apart from other areas of the image. If we look at works such as Schmelzwasser [Meltwater] , the figures actually seem refined and reserved, as if drawn on paper. The artist likes to emphasize that brushes and paint flow particularly well on linoleum and that it is well suited for the calligraphy of motion. The image background, he humorously remarks, can be “painted over as easily as a botched oil painting,” where the color also remains on the top surface, over underlying layers of paint.

Last but not least, the material, he explains further, is characterized by a certain resistance to pressure compared to canvas. This is of particular significance when Ruprecht von Kaufmann occasionally applies paint to individual parts of the canvas with a spatula.

It goes without saying that the formal changes mentioned also have an effect on content. Both graphical elements and individual areas left unpainted in the background at times lend the pictures a degree of abstraction that enters into an exciting dialogue with the rest of the painting. If one looks at the last works Ruprecht von Kaufmann created on canvas prior to switching to linoleum—the series with circus scenes—a tendency towards greater abstraction can already be seen in them. In contrast to earlier paintings, the background here is no longer as detailed, but is on closer inspection more reminiscent of sketched-out, geometric forms.

Ultimately this development leads to the linoleum works, in which individual image layers are distinguished from one another even more clearly than before—by graphical elements, by sections that dissolve into carved-out marks, and by fragments of foil applied in a collage-like manner. All of these contribute to the increasingly sculptural quality of the images—almost as if wanting to question the classical art historical distinction between genres of painting, sculpture, and drawing.

Content-wise, the individual layers represent different levels of meaning: for example, the four figures in Schmelzwasser [Meltwater] seen in the foreground of the image and painted directly onto the “raw” linoleum, represent four generations of the artist’s family. From left to right, seated, is Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s great-grandfather, standing next to him his grandfather, followed by his father placed diagonally in the image, and finally ending with the artist himself in a nearly horizontal position. The figures, dressed in military uniforms, are arranged clockwise, as if alluding to the factor of time and thus to transience.

It is interesting to note that Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s figure is only rendered graphically in outline, therefore escaping our perception, so to speak, while his forebears enjoy a greater physical presence. It seems as if the artist is alluding to the fact that his life can still be “filled out.” Rising up in the background behind the figures is an impressive mountain range, whose mid-section, now a melting glacier, has been removed and broken up by marks gouged out of the image ground.

Based on the clothes they are wearing, the figures shown are not only family members but also four generations of alpine troops. Ruprecht von Kaufmann, who completed his military service in mountain rescue, emphasizes how much this time fostered his love of nature. His abiding sense of responsibility towards it and, related to this, towards all future generations, is echoed in particular in the mountain theme that recurs throughout his body of work. This is where the location of yearning and the memorial are united—the latter in particular when the artist expresses the threat of melting glaciers and icebergs, not only in the work Schmelzwasser [Meltwater] mentioned above, but also in Jannu, Der Fjord [The Fjord], Natur [Nature] and Landschaft [Landscape]. Especially in the context of the current debate on climate action and the global Fridays For Future movement, these images are more compelling than ever. It is clear that Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s paintings should never be thought of solely in a subjective-autobiographical context, but that, above and beyond this, they must also be considered from a global, universally valid perspective. These are deeply personal images that we are only able to access via our own emotionality. In them we search for, recog- nize, question what is presented and develop it further. The power and powerlessness of the protagonists reflect and move us, above all because they show us how mutable man is, in both a negative as well as positive sense. The step from perpetrator to victim—and vice versa—is often less than a stone’s throw away from each other, and in this peculiar entangling we have a mutual effect on one another. In Ruprecht von Kaufmann’s painting, man’s facets are as varied and diverse as the range of tonalities between black and white. As viewers, we are challenged to enter into a dialogue in order to come to this realization in a dynamically variable manner.

Ruprecht von Kaufmann

(Germany , b. 1974)

Ruprecht von Kaufmann 魯普雷希特.馮.考夫曼 (德,b. 1974) 出生於德國慕尼黑,BFA洛杉磯藝術中心設計學院畢,曾任教柏林藝術大學、漢堡應用科學大學和萊比錫美術學院,現居住創作於柏林。作為一位突出的圖像敘事藝術創作者,他選擇研究圍繞著人的各種層面,利用當代繪畫的視覺語言,展現批判敘事與平行現實幻境。於歐洲各大城市倫敦、柏林、斯圖加特、奧斯陸、紐約展出;作品獲紐約知名收藏家族(Hort Family)、德國 Sammlung Philara 博物館、德國法蘭克福德意志聯邦共和國國家銀行等,眾多公私立機構永久收藏。

Solo Exhibitions

2023 Leben zwischen den Stühlen´, Buchheim Museum, Bernried 2022In the Street´, Kristian Hjellegjerde Gallery, London

2021 Just Before Dawn´, Galerie Thomas Fuchs, Stuttgart 2021Dreamscapes´, Cermak Eisenkraft Gallery, Prague

2020 The Three Princes of Serendip´, Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, London 2020Inside the Outside´, City Gallery Gutshaus Steglitz, Berlin

2019 Inside the Outside´, UN Headquarters, New York 2019Inside the Outside´, Museen Böttcherstrasse, Bremen

2019 Die drei Prinzen von Serendip´, Kunstsammlung Neubrandenburg, Neubrandenburg 2019Die Augen fest geschlossen´, Galerie Thomas Fuchs, Stuttgart

2018 Die Evakuierung des Himmels´, Kunsthalle Erfurt, Erfurt 2018Liederbuch´, Galerie Thomas Fuchs, Stuttgart

2017 Event Horizon´, Kristin Hjellegjerde Galelry, London 2016The God of Small and Big Things´, Galerie Crone, Berlin

2016 Phantombild-Blaupause´, Nordheimer Scheune, Nordheim, Germany 2015Grösserbesserschnellermehr´, Forum Kunst, Rottweil

2014 Fabel´, Georg Kolbe Museum, Berlin 2014Carna(va)l´, Museum Abtei Liesborn, Liesborn

2013 Die Nacht´, Junge Kunst e.V. Wolfsburg 2013Die Nacht´, Galerie Rupert Pfab, Düsseldorf

2012 Der Ozean´, Galerie Christian Ehrentraut 2011Altes Haus´, Galerie Rupert Pfab, Düsseldorf

2011 Zwischenzeit´, Neue Galerie Gladbeck, Gladbeck 2010Äquator Teil I´, Galerie Christian Ehrentraut, Berlin

2010 Herr Lampe´, Bundesbank, Frankfurt 2009Nebel´, Galerie Christian Ehrentraut

2009 Halbmast´, Philara Collection, Düsseldorf 2008Ruprecht von Kaufmann´, Galerie Rupert Pfab, Düsseldorf

2007 Eine Übersicht´, Konrad-Adenauer-Foundation, Berlin 2006Bathosphere´, Ann Nathan Gallery, Chicago

2006 Bathosphere´, Kunstverein Göttingen 2006Als mich mein Steckenpferd fraß´, Galerie Christian Ehrentraut, Berlin

2005 Bildwechsel´, Galerie Christian Ehrentraut, Berlin 2005Neue Zeichnungen´, Kunstschacht Zeche Zollverein, Essen

2003 `Of Faith and Other Demons´, Claire Oliver Fine Arts, New York

Publication

Dissonance – Platform Germany, DCV, Texte: Mark Gisbourne, Christoph Tannert, 2022, ISBN 978-3-96912-060-6

Leben zwischen den Stühlen, Distanz, Texte: Dr. Brigitte Hausmann, Daniel J. Schreiber, Sylvia Volz, 2020, ISBN 978-3-95476-354-2

Inside the Outside, Distanz, Maynat Kurbanova, Michele Cinque, 2019, ISBN 978-3-95476-270-5

Maynat Kurbanova, Michele Cinque, Inside the Outside, Distanz

Magdalena Kröner, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Kunstmarkt

Robert Hughes, Rolf Lauter, Julia Wallner, Ruprecht von Kaufmann 2005-2006, ISBN 978-3-00-020112-7

Leah Ollman, Los Angeles Sunday Times, ‘Painting a Mirror for Humanity’, 16. Juni 2002

Garrett Holg, Art News, ‘A futurist Manifesto’, Ruprecht von Kaufmann at Ann Nathan Gallery Chicago’, Januar Ausgabe 2002

Collection

Collection of the Federal Republic of Germany

Collection of the German Bundestag

Collection of the National Bank of the Federal Republic of Germany, Frankfurt

Coleccion Solo, Madrid

Collection Ole Faarup, Kopenhagen

Collezione Coppola, Vicenza

Hort Family Collection, New York

Uzyiel Collection, London

Sammlung Philara, Düsseldorf

Sammlung Hildebrand, Leipzig

Sammlung Holger Friedrich, Berlin

Sammlung Museum Abtei Liesborn, Liesborn

Sammlung Veronika Smetackova, Prague

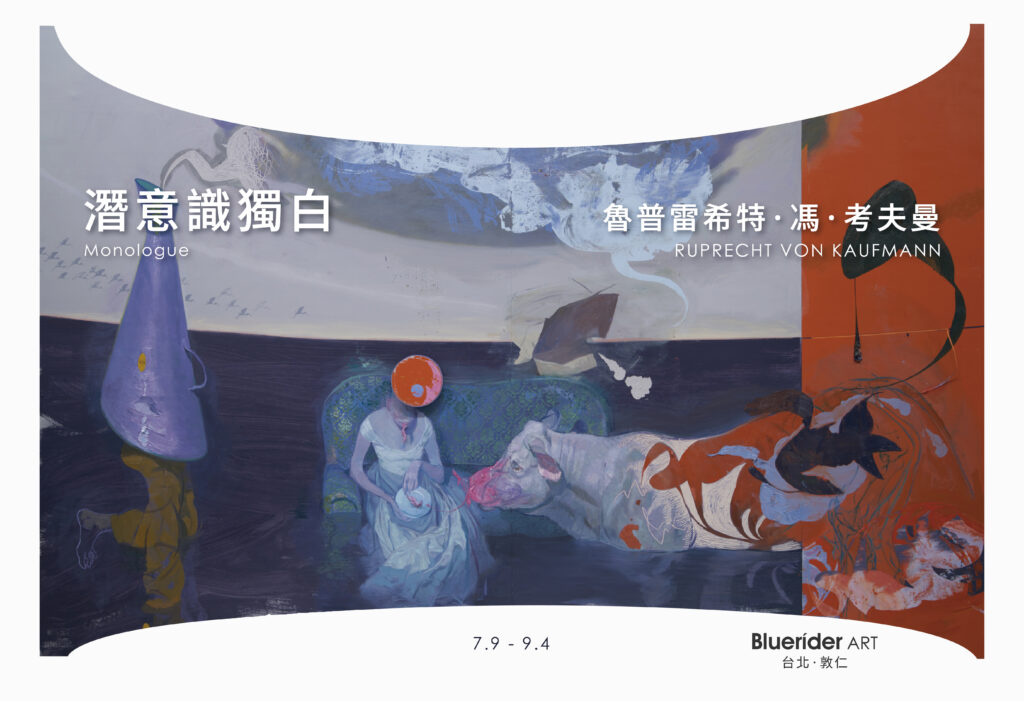

「潛意識獨⽩ Monologue」

魯普雷希特.馮.考夫曼 Ruprecht von Kaufmann在台首個展

開幕式(藏家預覽):2022.7.9 Sat. 2pm – 5pm

大眾開放:2022.7.9 Sat. 5pm – 7pm

展期:2022.7.9 – 2022.9.4

Venue:Bluerider ART Taipei·DunRen

Tue.-Sun., 10am – 7pm

1F, No.10, Ln. 101, Sec. 1, Daan Rd., Taipei

Currently