Exhibition

Trailer

Exhibition Tour

Installation

Opening Video

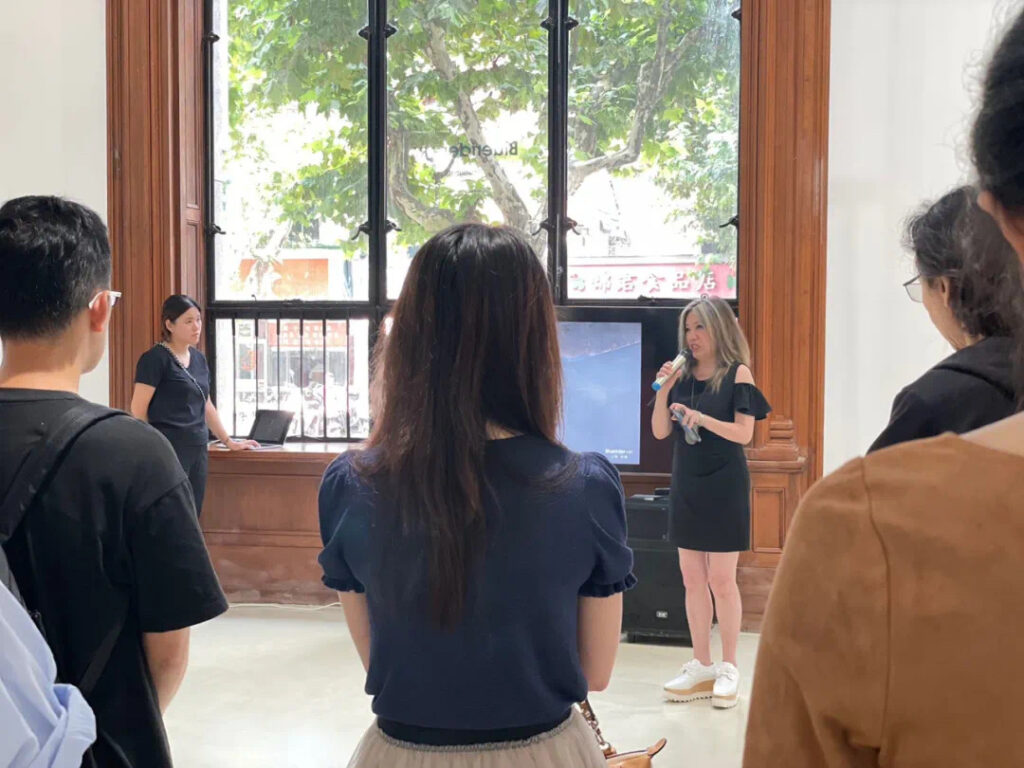

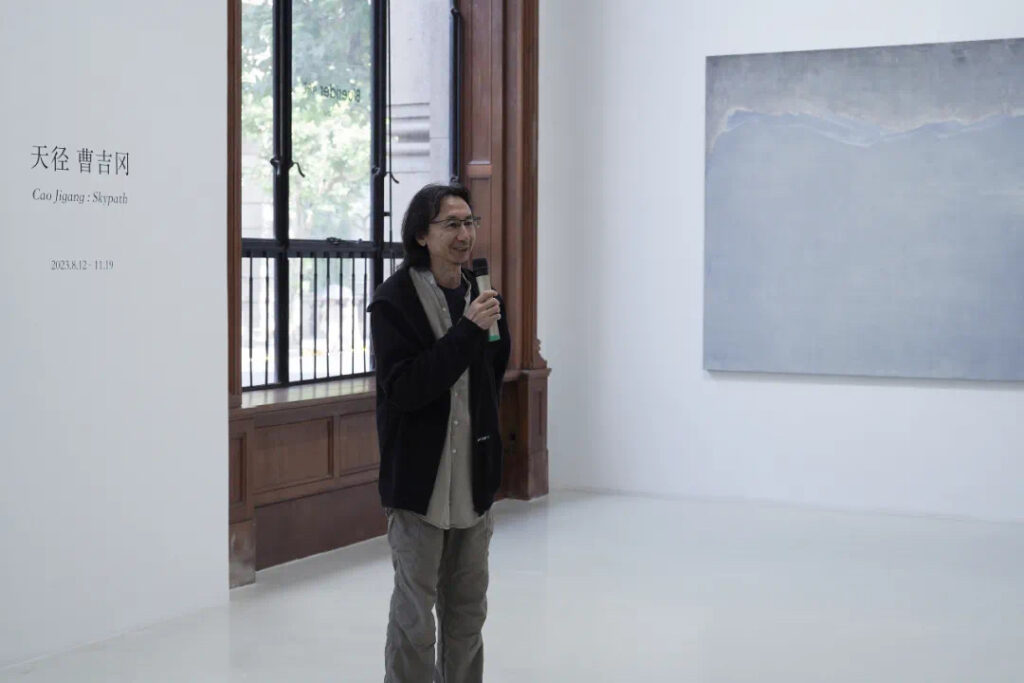

Opening Photos

(開幕酒會因來賓眾多,未及留影的貴賓們請包涵)

‘天徑’ -曹吉岡個展 ‘Cao Jigang:Skypath’

Shanghai·The Bund

Bluerider ART上海·外灘即將於2023年8月12日週六,隆重推出 ‘天徑’-曹吉岡個展‘Cao Jigang:Skypath’。曹吉岡Cao Jigang 為Bluerider ART 代理唯一中國資深藝術家,亦是Bluerider ART 於九月倫敦空間開幕群展中,極具代表性之中國藝術家。此次個展是繼Bluerider ART 台北·敦仁2020年‘當坦培拉遇見山水’-曹吉岡個展,睽違三年後,首度於大陸舉辦的曹吉岡Cao Jigang 2023年全新創作個展。

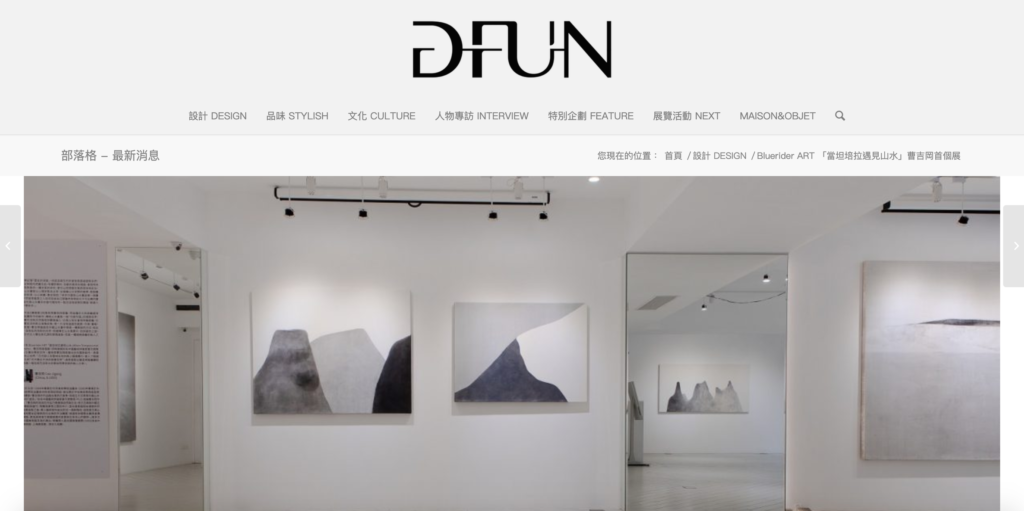

Bluerider ART 台北·敦仁 2020年 ‘當坦培拉遇見山水’-曹吉岡個展

Cao Jigang, was graduated from Material Expression Studio of Oil Painting Department of China Central Academy of Fine Arts, also was a professor at Foundation Year Program Department of China Central Academy of Fine Arts. Currently living, working in Beijing, China, and exhibiting widely in museums and curated exhibitions. Cao Jigang received the Silver Prize in The National Exhibition of Fine Arts in 1999. His work is included in public collection including The National Art Museum of China in Beijing, Shanghai Art Museum and New Hall of China International Exhibition Center in Beijing.

Zhuzhong Art Museum, Beijing

National Art Museum of China, Beijing

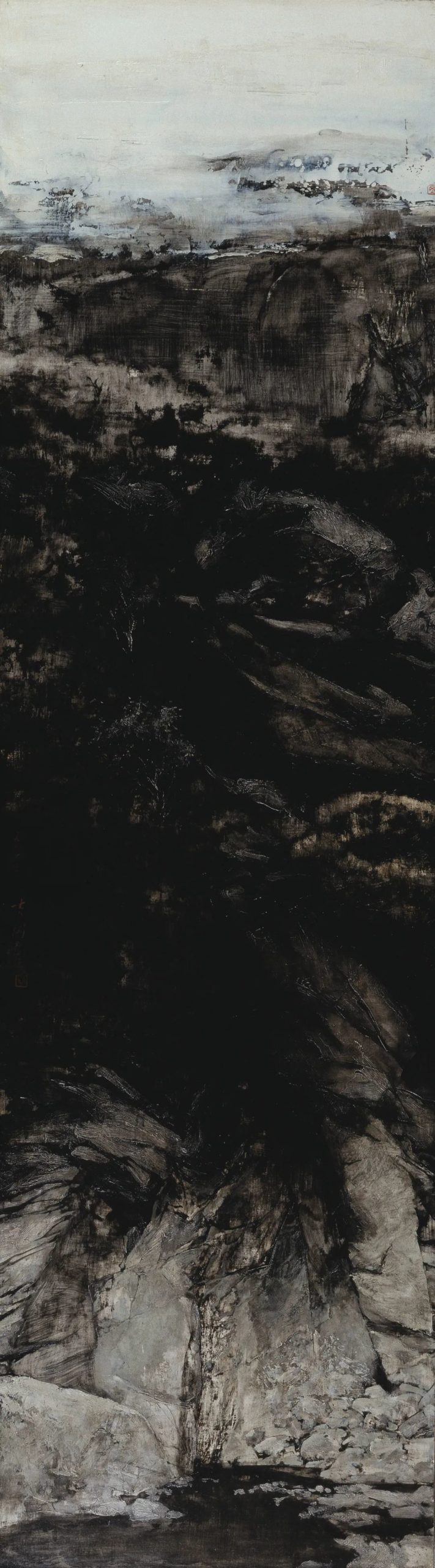

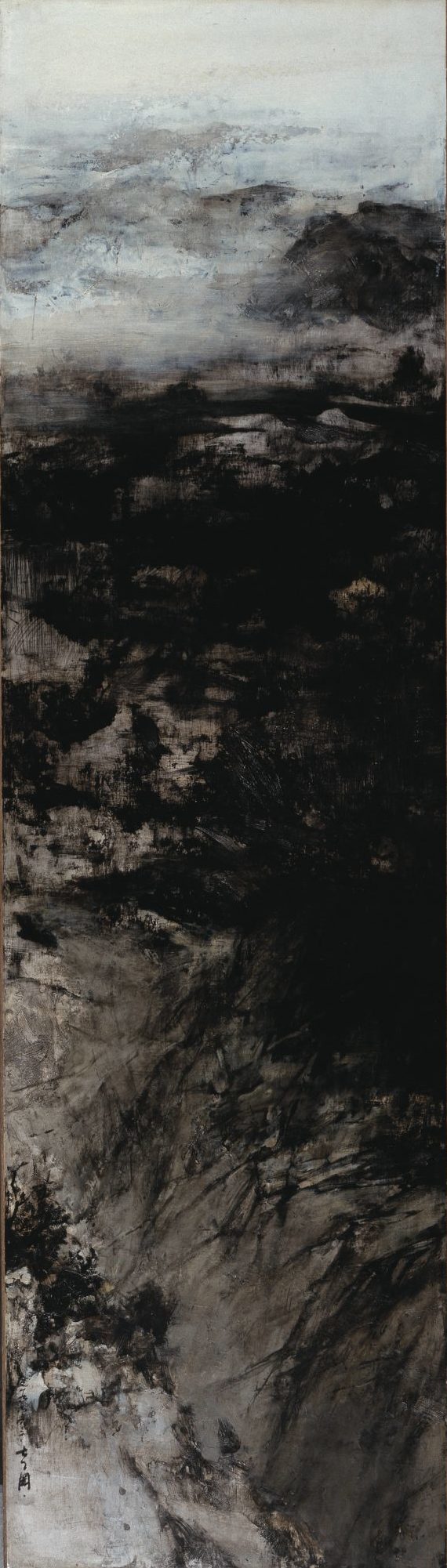

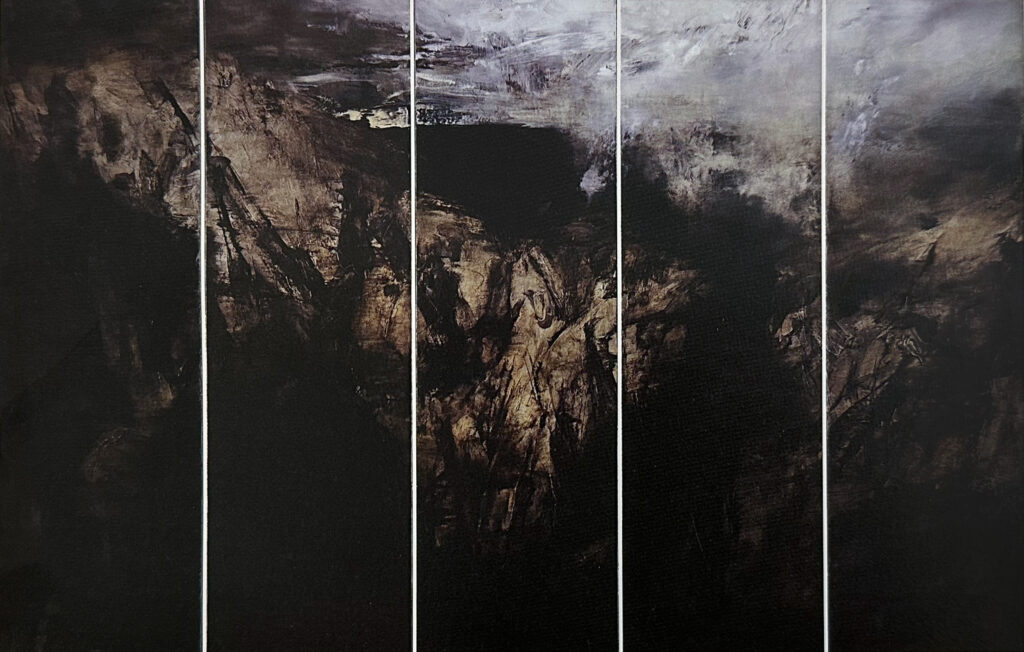

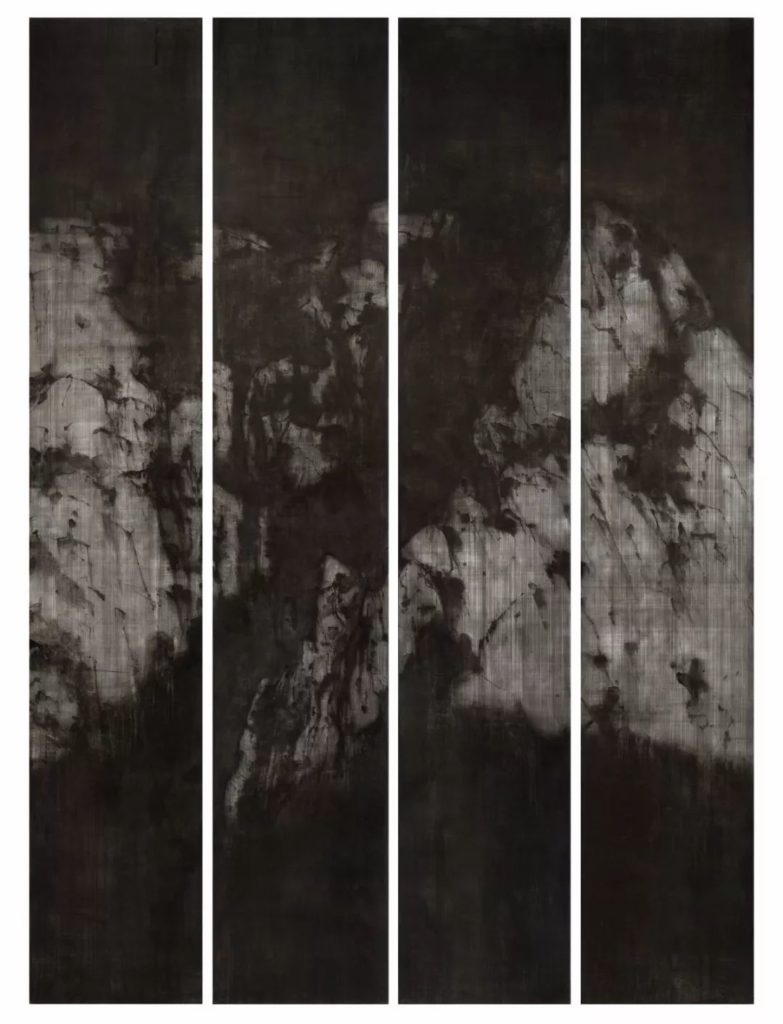

曹吉岡Cao Jigang 自美院起40年創作期間歷經幾個不同時期演變:“油畫長城”時期,以純粹歐洲油畫語言,表現長城荒涼廢墟感。 “鉛筆劃山水”時期,創新以鉛筆劃染過程融鉛,呈現如水墨山水磅薄氣勢。 “坦培拉山水”時期,則改良古老坦培拉技法,創出大型《荒寒》系列、七米巨幅《廣陵散》令人震撼作品。自2020年疫情期間於Bluerider ART台北·敦仁個展 ‘當坦培拉遇見山水‘逐漸走向極簡風格。

曹吉岡|廣陵散|2012|400x720cm| 亞麻布坦培拉

曹吉岡|荒寒9|2021|160 x 300 cm|亞麻布坦培拉

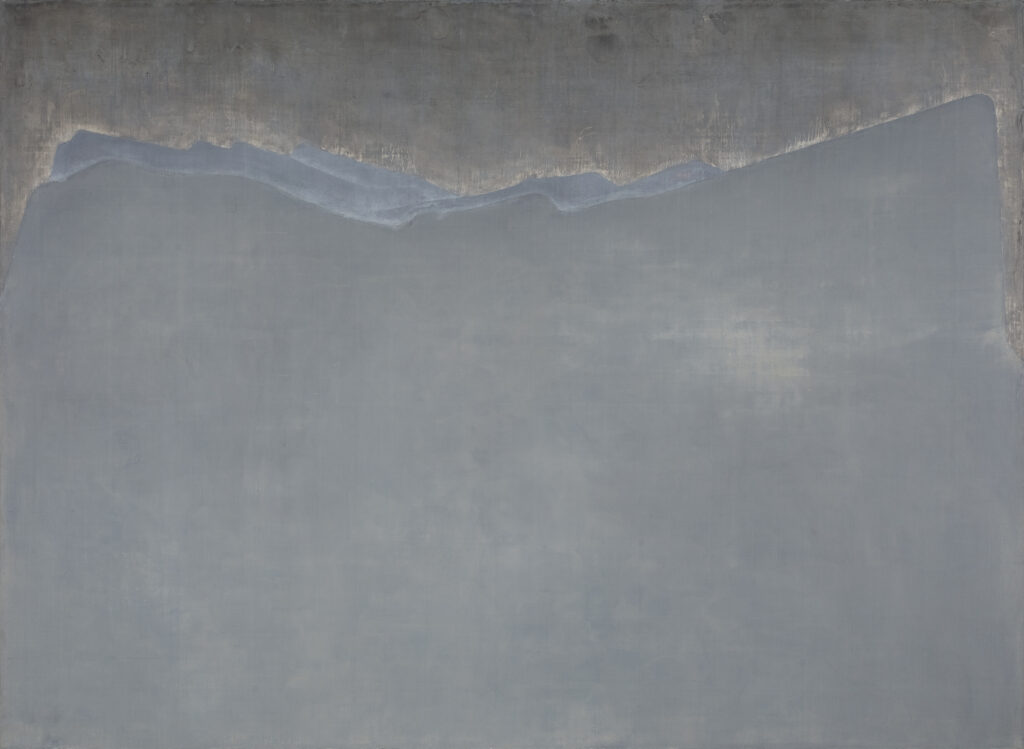

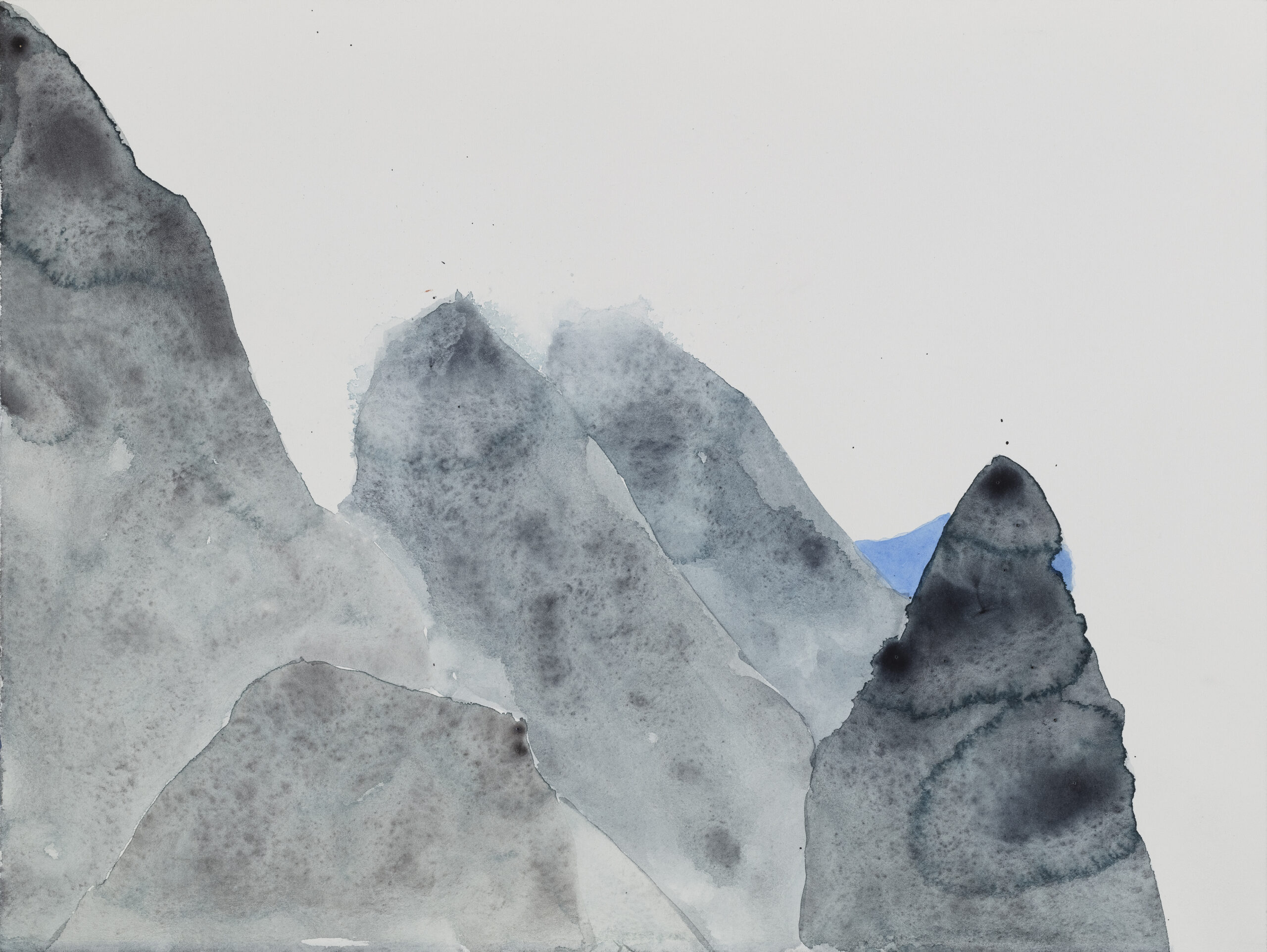

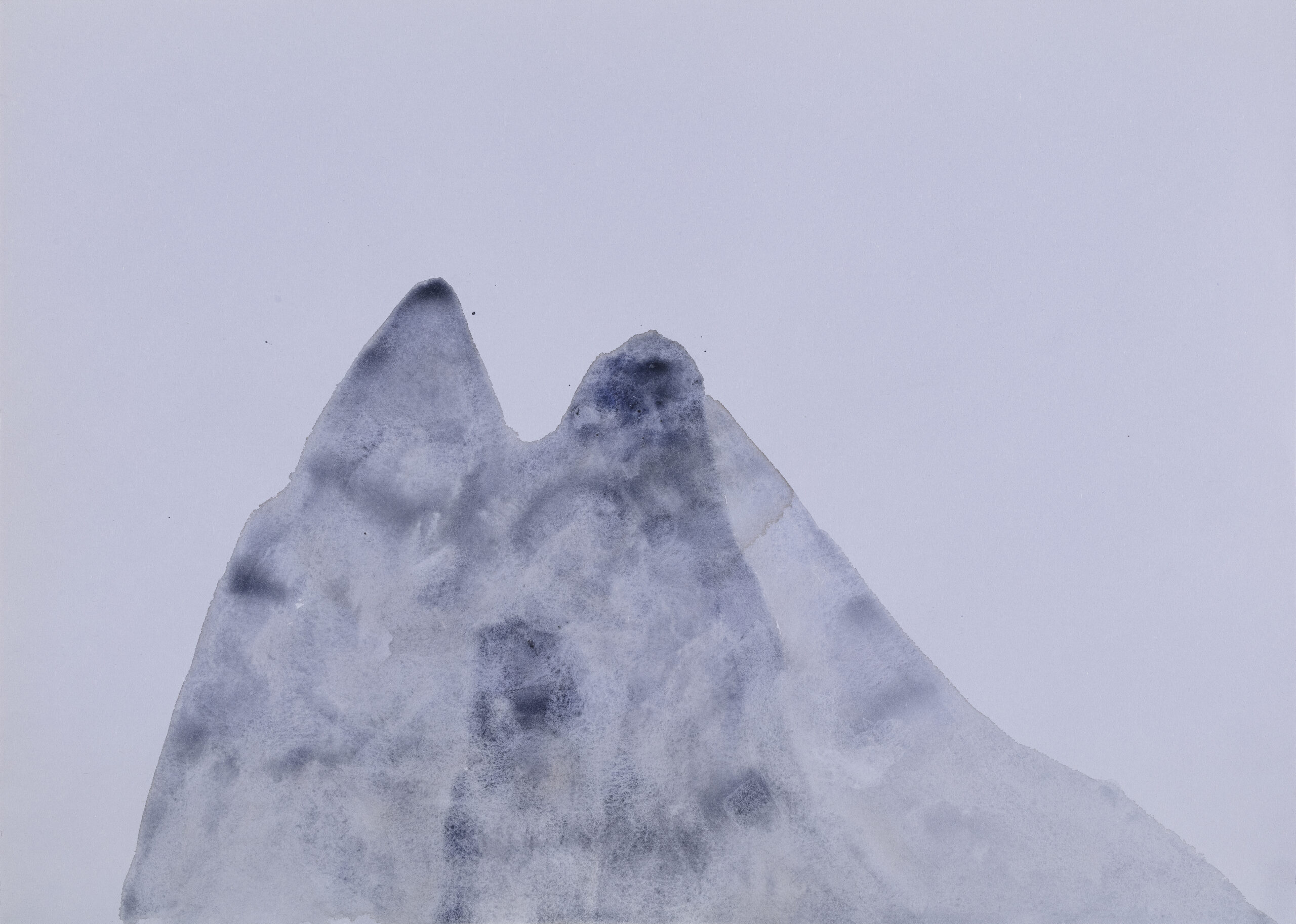

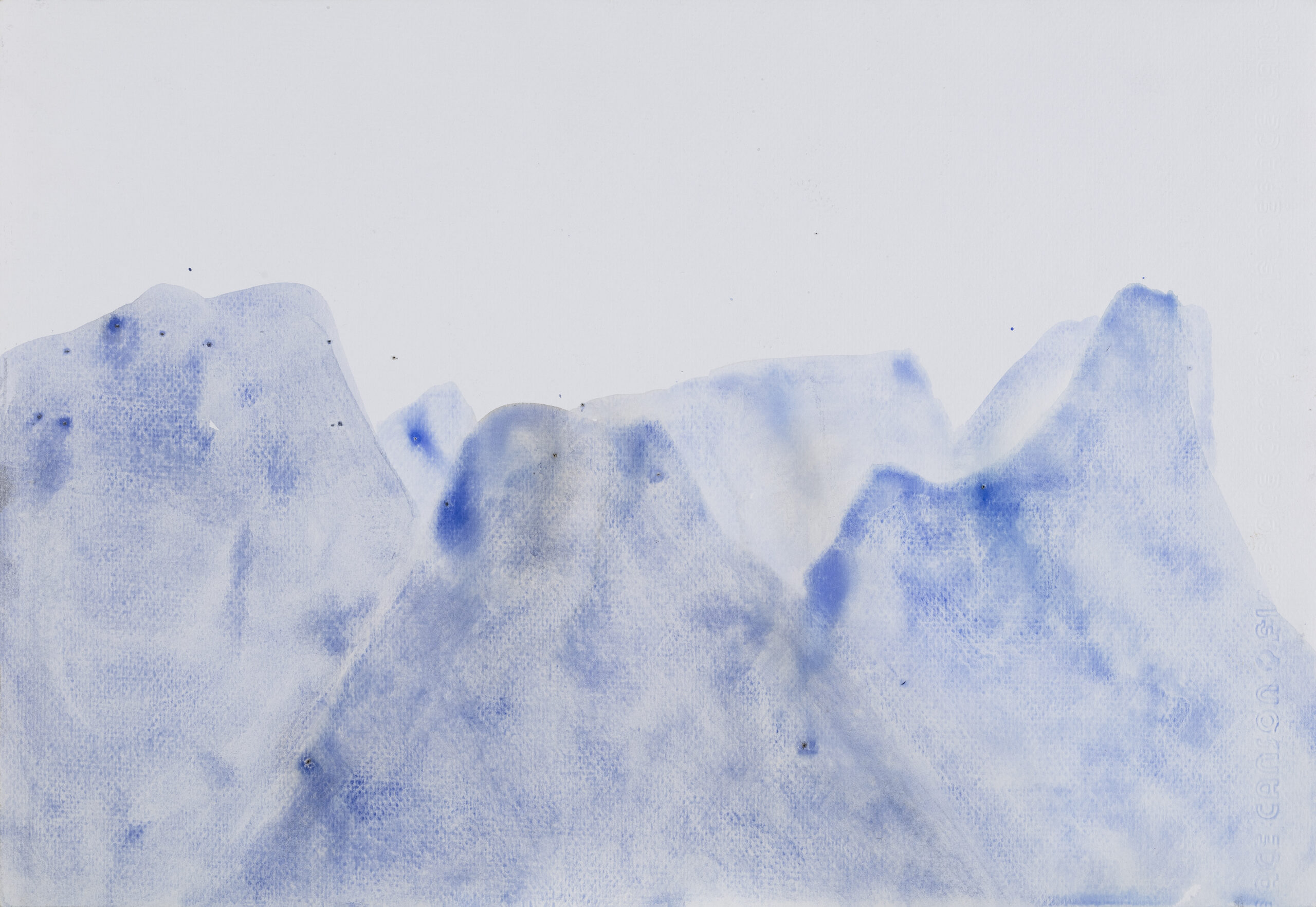

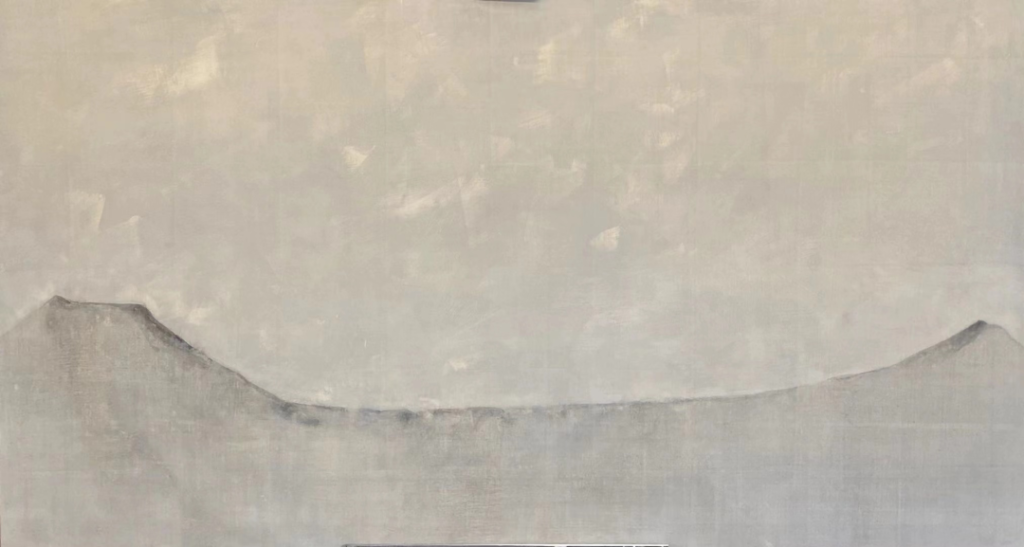

Cao Jigang’s work transcends the limits of either Chinese or Western painting, and he tries to demonstrate the “emptiness” in Chinese ink art by assorted methods. The way to depict “emptiness” in ink and wash painting is “Liu Bai”, leaving blank, not painted. It corresponds with the concept called “Wu Wei,” doing nothing, to represent the void. In contrast, the artist intends to show the “emptiness” by “You Wei,” doing something. He smears his art piece dozens of times, and therefore, layers of thin material can settle down while the painting gets dry. The “emptiness” formed through this thus has a strong sense of texture and materiality, and the feeling of heaviness. This kind of “emptiness” is “substantial” and the “void” comes from the “adequate”.

Ni Zan, a Chinese painter during the Yuan and early Ming periods, walked alone on his pilgrimage path of art and eventually entered an ultra-personal lonely world where there is no “flower blossom or water flowing.” Cao Jigang noted he would hope to follow Ni’s footsteps and reach a deserted and desolate uninhabited place, without flowing water or blooming flower. Although Chinese traditional landscape painting creates an ideal world where people can visit and live there, there is no pathway for viewers to enter Cao’s painting. His art keeps distance from human being and society. It is a confrontation or counter-image of real life. The landscape in his artwork has no warmth. It is cold, grim, and triggers no desire.

此次Bluerider ART上海·外灘‘天徑’-曹吉岡個展 ‘Cao Jigang:Skypath’ 將展出曹吉岡Cao Jigang近三年全新創作十數幅。針對此次個展曹吉岡Cao Jigang表示:「以前我做風景的山水化研究,自從2020年台北個展開始,畫面就逐漸傾向於簡約和單純,是否有水墨和山水的意味變得不重要,可以說是在慢慢的極簡化和去山水化,如何在畫面上減去更多的東西,是我目前關注的重點,怎麼能少畫一點、再少畫一點,簡單的造型和飽和度極低的色彩,使畫面變得清冷和寡淡」。 40年創作能量源源不絕的曹吉岡Cao Jigang,從長城廢墟到《廣陵散》的悲壯,從山水空寂到《荒寒》的沒有溫度,從超越地表到道法自然、天人合一的 《天徑》,一路走來一如他所說:「即便世間事物並不存在完美,然而完美仍值得追求。」

‘天徑’ -曹吉岡個展‘Cao Jigang:Skypath’

展期:2023.8.12 – 11.19

開幕日:2023.8.12(六)4pm-6pm(藝術家在場)

地點:Bluerider ART上海·外灘(上海黃浦區四川中路133號)

Works

Artist

Cao Jigang

(China, b.1955)

出生於北京,1984年畢業於中央美術學院油畫系,2000 年畢業於中央美術學院油畫系材料表現研修組,曾任教於中央美術學院造型學院基礎部,現居住創作於北京。曹吉岡的創作融合東西方美學、文人思想,早期以油畫描繪長城廢墟,歷經不同時期鑽研,後選擇歐洲古老坦培拉技法,畫出巨幅《廣陵散》、《荒寒》系列,作品獨有的半透明光感、瓷釉般溫潤的玉質感,以「有為」的層層塗抹,表達「虛空」意境,近期「去山水化」、「極簡」風格,更打開天人哲思的想象空間。曾獲第九屆全國美展銀獎(1999)並多次於中國美術館及海內外展出,作品由中國美術館、上海美術館等機構,以及兩岸三地資深藏家永久收藏。

Zhuzhong Art Museum, Beijing

National Art Museum of China, Beijing

曹吉岡Cao Jigang 自美院起40年創作期間歷經幾個不同時期演變:「油畫長城」時期,以純粹歐洲油畫語言,表現長城荒涼廢墟感。「鉛筆畫山水」時期,創新以鉛筆畫染過程融鉛,呈現如水墨山水磅薄氣勢。「坦培拉山水」時期,則改良古老坦培拉技法,創出大型《荒寒》系列、七米巨幅《廣陵散》令人震撼作品。自2020年疫情期間於Bluerider ART台北·敦仁個展 ‘當坦培拉遇見山水‘逐漸走向極簡風格。

中國藝術哲學評論家夏可君Xia Kejun博士評論曹吉岡創作:「中國古代的「三遠法」,在曹吉岡的繪畫上,以更為簡化抽象的方式呈現出來,這一片冰心玉印的世界,山形的輪廓,僅僅留下一抹抹透明又輕逸的痕跡,其空寒安寧又煙色輕染的氣息,也許就是北宋的王詵,元代的倪瓚,明代的董其昌與王翬,無數次在岩巒疊嶂與煙嵐浮動上要傳達的隱秘詩意。儘管進入現代性之後,面對寫生與照相的雙重壓力,此詩意的技藝觸感,幾乎失傳了,但在曹吉岡這裡,借助於坦培拉的技藝,空寒意境的靈暈得以重現。曹吉岡的坦培拉作品乃是連接自然與生活,西方古典與中國古典,傳統與當代,現實與夢想之間的中介,是在趙無極與朱德群的抒情風景抽象之後,華人藝術家所給出的另一個新階段。」

曹吉岡Cao Jigang 透過改造因過於耗時繁復而式微的歐洲古老坦培拉(蛋彩畫)繪畫技法,有如修行般緩慢的多層次製作打磨,借鑒水墨罩染方式,保持間薄余留的痕跡,以保留其無法被油畫與其它材料替代的審美價值,半透明內在的光感、瓷釉般溫潤的玉質觸感,14-15 世紀藝術家喬托(Giotto di Bondone)、波堤切利(Sandro Botticelli)的作品皆使用坦培拉精細創作,經過幾個世紀無瑕疵,歷久彌新。

傳統水墨畫的「虛空」是留白,是不畫,是以「無為」來表現虛空的概念,曹吉岡Cao Jigang則反其道而行,十數遍甚至數十遍的「有為」塗抹,一層層虛薄的材料在乾燥的時間過程中沈積下來,這樣形成的「虛空」有了結實的觸摸感、物質感和厚重感,形成一種「實體」的、從「有」中而來的「無」。曹吉岡Cao Jigang認為不必刻意以東方或西方的畫法結構去看待他的作品,坦培拉作為成全虛無水墨的方法,介於抽象與具象之間,這是他刻意打造,模糊文化識別的趣味性。

面對強大的傳統山水,他只取極少的元素於畫中,生成不同於兩者的迭加態,這種迭加態是西方畫法的堅固性與傳統水墨的流動性之間的一種平衡,簡化為宋代禪意山水的淡遠,幾乎去除了自然山水的意象。不論是黑白灰強烈對比的荒涼、孤寂,或是近乎無情緒的中性灰色調,如同一抹時光的淡痕,自古至今,由近而遠,淡泊而悠然。

2023年Bluerider ART上海·外灘‘天徑’ 曹吉岡個展 ‘Cao Jigang:Skypath’ 將展出曹吉岡Cao Jigang近三年全新創作十數幅。針對此次個展曹吉岡Cao Jigang表示:「以前我做風景的山水化研究,自從2020年台北個展開始,畫面就逐漸傾向於簡約和單純,是否有水墨和山水的意味變得不重要,可以說是在慢慢的極簡化和去山水化,如何在畫面上減去更多的東西,是我目前關注的重點,怎麼能少畫一點、再少畫一點,簡單的造型和飽和度極低的色彩,使畫面變得清冷和寡淡」。40年創作能量源源不絕的曹吉岡Cao Jigang,從長城廢墟到《廣陵散》的悲壯,從山水空寂到《荒寒》的沒有溫度,從超越地表到道法自然、天人合一的 《天徑》,一路走來一如他所說:「即便世間事物並不存在完美,然而完美仍值得追求。」

Cao Jigang’s creative process in different stages 1984-2022

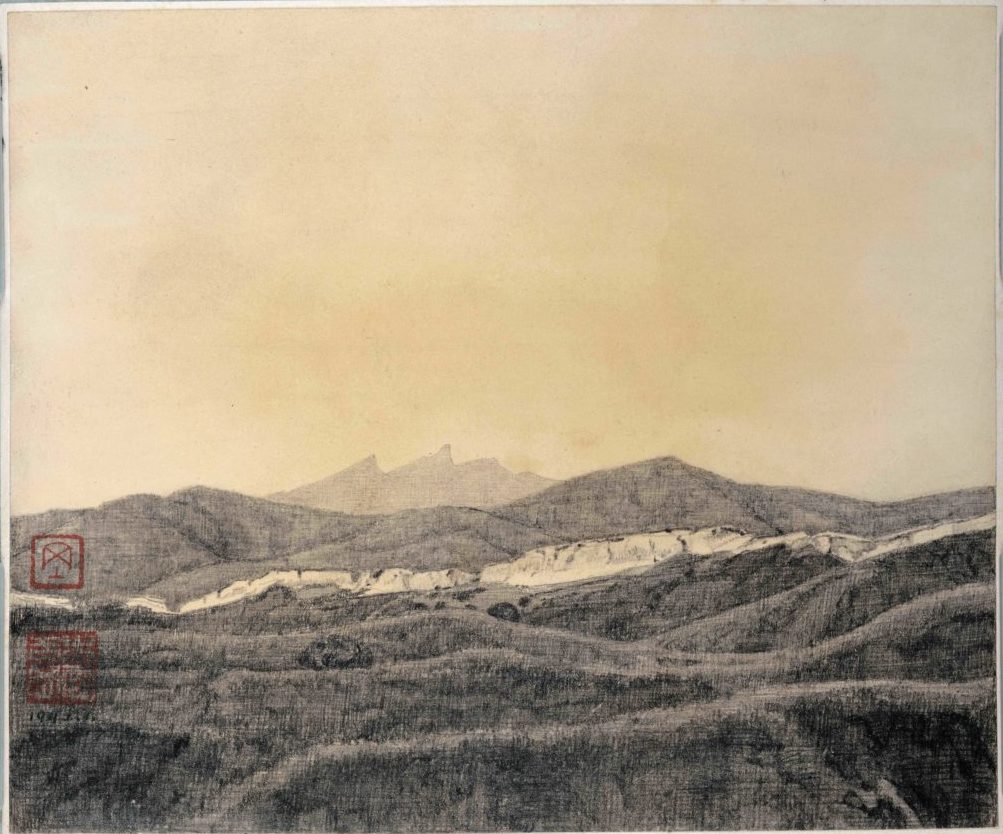

The representative work of his first phase is ‘The Great Wall’ series created in the 1990s. Although the works showed the characteristic of Chinese academic art that revealed realism in landscape sketching, Cao Jigang particularly chose the Great Wall as his solely sketching object. The artwork demonstrated his attempt to set memorial still lives off with a vast background not only between natural ruins and historical symbols, but also broad poetry and individual loneliness. The work forms a painting language that consists of a firm shape with boundless meanings, as well as creating his dual-return mindset of naturalizing history while historicizing nature. He is capable of exploring the in-depth sorrow that hidden or buried in history.

曹吉岡 長城

這批長城畫了可能有 5-6 年,到了 1990 年代初,當時覺得不想再用這種語言來畫油畫,希望有所改變就做了一些嘗試。因為本身也是喜歡中國的山水畫,就希望能夠在兩者之間有一個融合。開始用鉛筆畫了一些鉛筆的作品。1990-1991 年在美術館辦了一個長城的展覽,在辦展覽之前的準備工作的時候, 因為我都是油畫都是尺幅比較大,我希望有一些小的畫,能夠穿插在裏面展覽的空間比較活躍。如果全是大幅的油畫會顯得有些陳悶,所以想劃一些小畫,所以想到用鉛筆畫在材料和表現手段上有不同,會顯得展覽面貌更豐富,所以就嘗試鉛筆在紙上來畫。相對來說也比較快,可以在比較短的時間,準備出需要的數量的鉛筆畫,所以用鉛筆來畫。畫的過程中用了一些松香定畫液,一般是噴在素描上達到固定鉛粉的作用。我是用毛筆沾著定畫液染在這個鉛筆畫上,染的過程把鉛融化了一部分,所以出現了一種像水墨或者水彩或者銅版畫,這是一個偶然的發現。

Stepping into the third phase from 2010s, Cao Jigang still focused on landscape sketching. However, he integrated the visual memory of literati landscape paintings since the Song Dynasty, and he ingeniously merged the natural vividness with historical-cultural images. Taking the ‘Guangling Melody’ as an example, he managed to mourn the historical sorrow with modern majesty. Meanwhile, he rejuvenated the mist vividness of landscape sketching by presenting the implicit textures as infra-mince shadows. On the other hand, regarding the series artworks of ‘Taihu Stone’, the paradoxical combination of the firmness of still lives and the vastness of quaint tone. The mountains and stones are like abundant flowing Zen, which injects the beauty of lightness that the glazing of tempera paintings never had. It seems like the objects were given spiritual breathes.

大約2000年前後,我開始研究坦培拉進行創作。坦培拉是一個翻譯詞,Tempera譯音,是混和攪拌的意思。坦培拉,是用油和水兩種材料攪拌和成一種媒介,用這種媒介來畫的畫就叫坦培拉繪畫。坦培拉繪畫媒介也分幾種, 雞蛋坦培拉是最常用的一種材料,所以一般覺得坦培拉就等同於蛋彩。雞蛋坦培拉或稱蛋彩,坦培拉大多都指這個蛋彩坦培拉,它的特點最早可以追溯到公元前就開始有這種材料,這是一種非常復雜、非常麻煩的一種材料和繪畫的方式,因為它需要一個比較漫長的時間,慢慢地達到一種效果,它經過多年的改進,發展之後逐漸變成油畫。油畫它有很多方便之處,所以坦培拉這種材料基本上沒人再采用了。雖然這種材料非常麻煩,但是它有一種其他材料無法替代的審美價值,比方說它的半透明性,那種內在的光感,像瓷釉壹般或像玉一般的那種溫潤的質感,這個是任何一種材料替代不了的,這也是我為什麽選擇它的原因。

坦培拉因為這種材料特點,是一種半透明狀,仔細看作品你會看進去,你會看到色層下面的東西,操作好之後會有這種效果,會有往後滲透的感覺。所以創作過程是一個非常理性的過程。因為需要事先有一個計劃預判,你通過幾步之後想要達到什麽效果。雖然之中有些變化,但事先必須要有設想在裏面,然後一步一步的通過一遍一遍的染,逐漸把你想要的東西顯現出來,所以不能急躁,必須是緩慢地進行,而且如果你有激情沖動,也必須控制把它在理性的畫面內,不讓它干擾你的這種很有條理的步驟,一步一步的方法就像一種慢慢修行,每張畫都是緩慢讓它逐漸伸展完成的一個結果。

媒體報導Press

曹吉岡

(China, b.1955)

Education

1984 Oil Painting Department of Central Academy of Fine Arts

2000 Oil Painting Materials Researcher Studio, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing

Upcoming Exhibitions

2024 Sept. Cao Jigang Solo Show, Bluerider ART, Mayfair, London

2023 Sept. 宇宙家園Homeland Universe群展, Bluerider ART, Mayfair, London

Selected Exhibitions

2023 Skypath Cao Jigang solo exhibition, Bluerider ART, Shanghai

2022 Solo show at Taipei Dandai, Bluerider ART, Taipei

2021 “White+White”, Arton Art Centre, An Academic Curating Group show, Shenzhen

2021 Duo show at JINGART, Bluerider ART, Beijing

2020 “When Tempera met Shansui”Solo show, Bluerider ART , Taipei

2020 "White into Blank" Group Show, 798 Art District Whitebox Art Center,

Beijing, China

2019 Cao Jigang on works Solo Exhibition, Shanghai No. 8 Bridge, Shangha

2018 "Parallel Horizons — Chinese Oil Painters with European Peer Exchange

Exhibition", Bastille Design Center, Paris, France

2018 “The Fifteen Sceneries·Cao Jigang Solo Exhibition”, Zhuzhong Art Museum, Beijing

2015 “Cao Jigang Little Painting Works Exhibition”, Zhuzhong Art Museum, Beijing

2014 "In the Silence Between Two Waves" Group Show, BRIC Art Space, Italy

2014 “Lion Forest”,Musée du Louvre, Paris

2014 “Empty Cold: Chora-topia of Nature”, Soka Art Center, Beijing

2014 “Abstraction and Nature”, Zhuzhong Art Museum, Beijing

2014 “Steps of Exploration”, Jinan Art Museum, Shandong

2013 “Darkness Visible: Group Show of Ten Artists from China and US” National Art Museum of China, Beijing

2012 “In Time: 2012 Chinese Oil Painting Biennial”, National Art Museum of China, Beijing

2012 “Vaulting Limits”, Tenri Cultural Institute, New York

2011 “Giving and Receiving”, Art Museum of University of Colorado, Colorado

2009 “Contemporary Expression of Traditional Thoughts”, National Art Museum of China, Beijing

2008 “Image-China”, National Art Museum of China, Beijing

2008 “In Depth: Exhibition of Faculties of Central Academy of Fine Arts”, Today Art Museum, Beijing

2007 "Eastern Vision – Sino-Korean Modern Art Exhibition", China Millennium

Monument, Beijing, China

2007 “Facing and Dealing: Sino-Us Artist Exhibition”, National Art Museum of China, Beijing

2003 “Beijing Biennial”, National Art Museum of China, Beijing

2001 “Conversation between Durer and Chinese Landscape Painting-Exhibition of Cao Jigang”, Beijing

2001 ”歲月之聲“ -李天祥、趙友萍、趙友蘭、曹吉岡、何衛、何寧六人家族藝術群展 , “Autumn Mountain” (collection), 上海美術館, 中國上海

2000 Chinese Landscape Painting Exhibition”, Finland-Chinese Artists Association

1999 The Ninth National Fine Arts Exhibition - silver award - "Cangshan is like the sea"

1999 北京市慶祝建國 50 周年美術作品展” 中國美術館 – 優秀獎 – “蒼山如海”, 中國北京

1998 Chinese Landscape Exhibition, National Art Museum of China, Beijing

1996 The First China Oil Painting Society Exhibition

1994 The 8th National Fine Arts Exhibition, National Art Museum of China, Beijing

1992 Cao Jigang Solo Exhibition, National Art Museum of China, Beijing

1990 Oil painting group show, Hao Zhen Gallery Pte Ltd, Singapore

1989 上海第七屆全國美術作品展 – 《長城組畫——荒戍》, 中國上海

Awards

2014 Excellence award at the 2014 French National Artists Association International Art Salon Exhibition – “Lion Forest””獅子林”-Gold Award

1999 The 9th National Fine Arts Exhibition – “蒼山如海”- Silver Award

Beijing Fine Art Exhibition For 50th Anniversary of Funding PRC – “蒼山如海”-outstanding award

1994 Xinzhulian Chinese Traditional paintings and oil paintings Exhibition – “深谷淺溪”-Silver Award

Collections

2009 “The Hua Shang Mountain“by National Museum of China

2008 “The Great Wall Series I”by National Museum of China

2001 “Autumn Mountain” by Shanghai Fine Art Museum

1997 “The Forest” by China International Exhibition Agency

1995 “Woman Nude”by China International Exhibition Agency

1995 “The Great Wall Series” Thunder by China International Exhibition Agency