(China, b.1955)

"Even though perfection may not exist in the world, it is still worth pursuing." - Cao Jigang

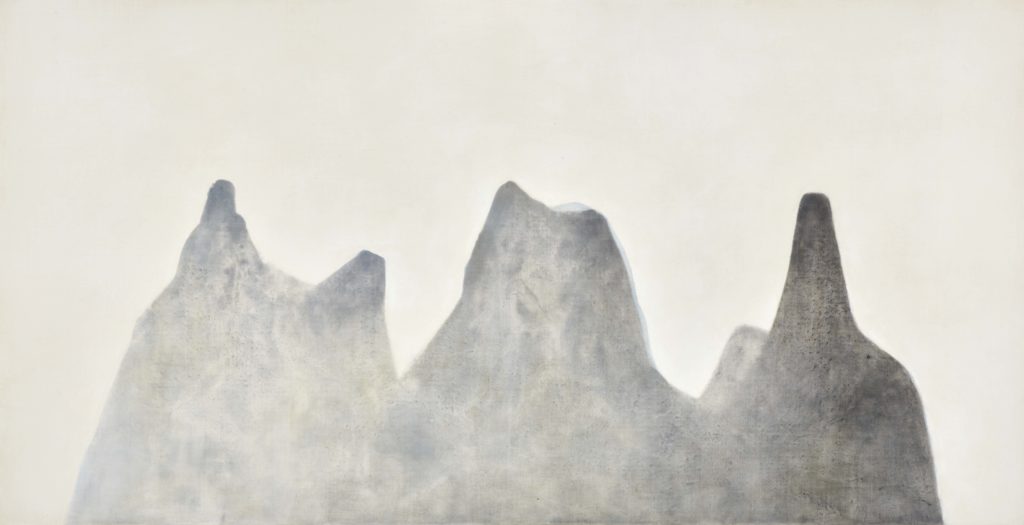

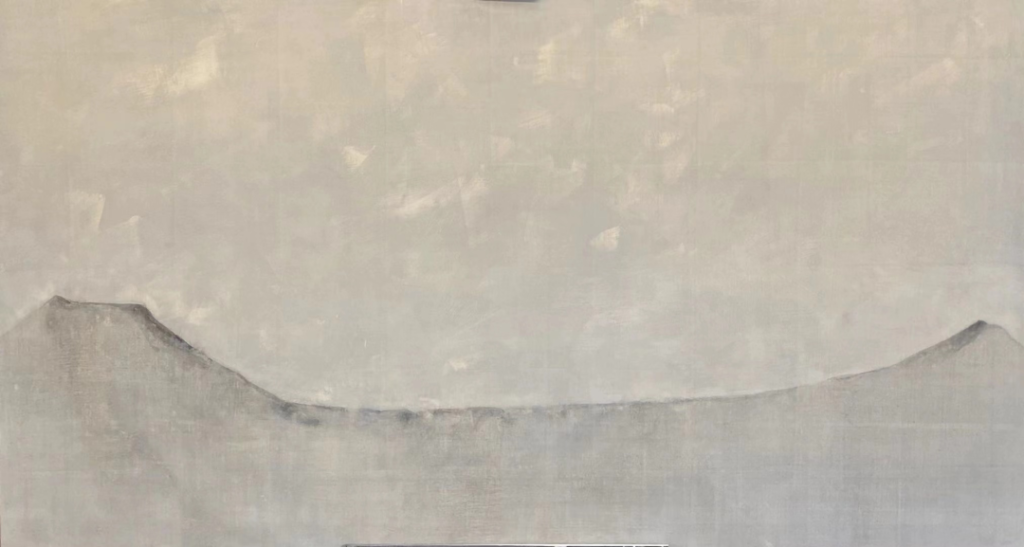

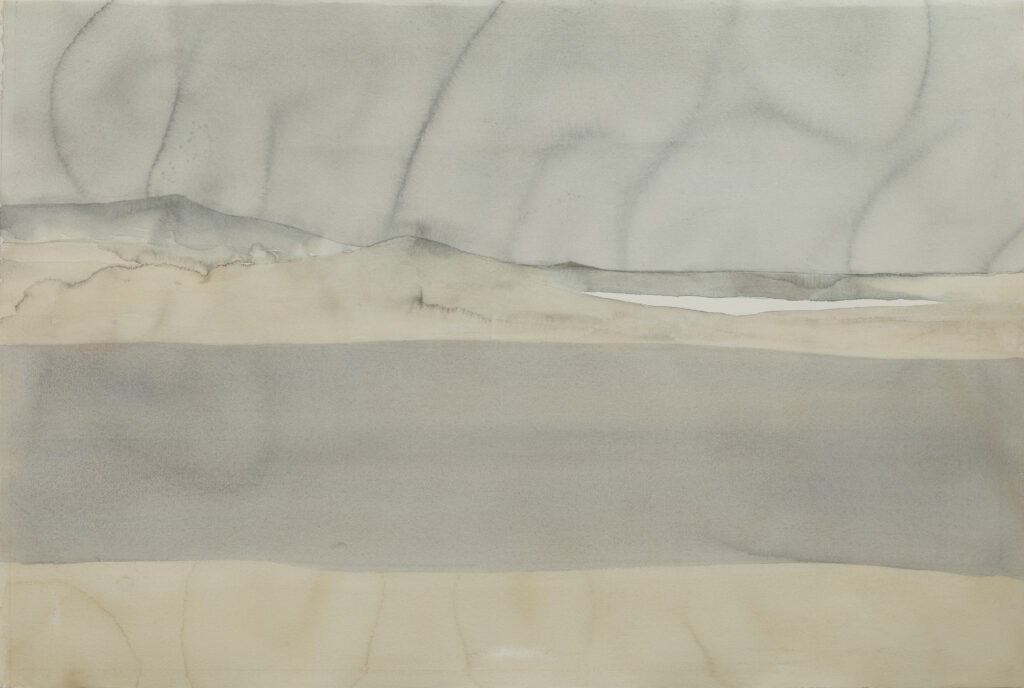

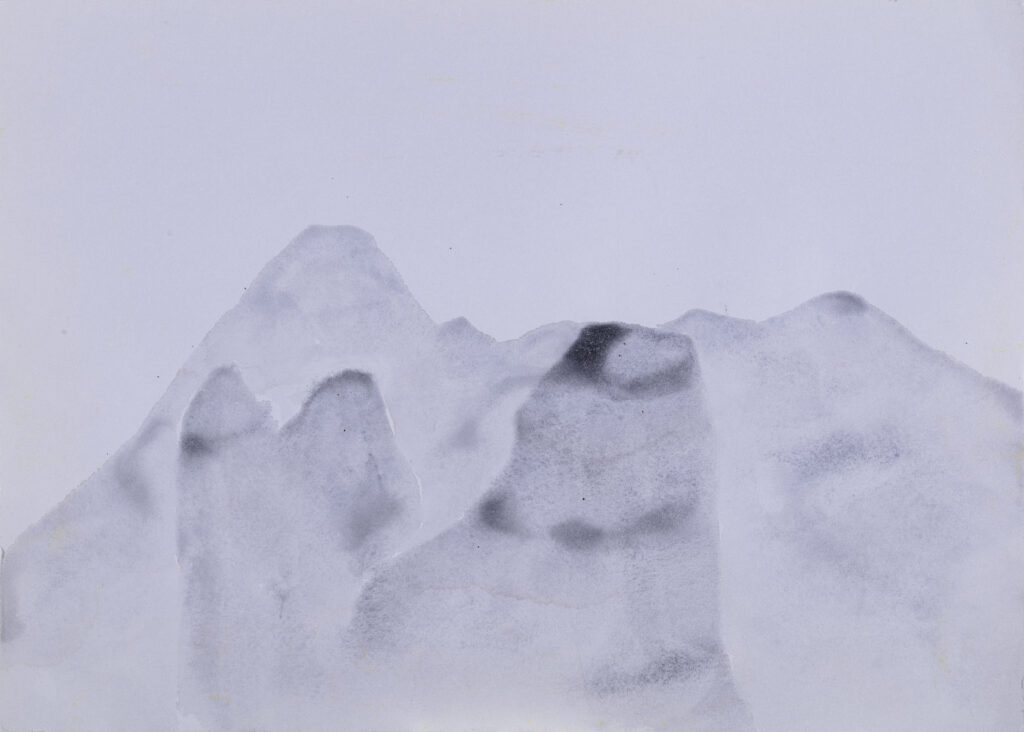

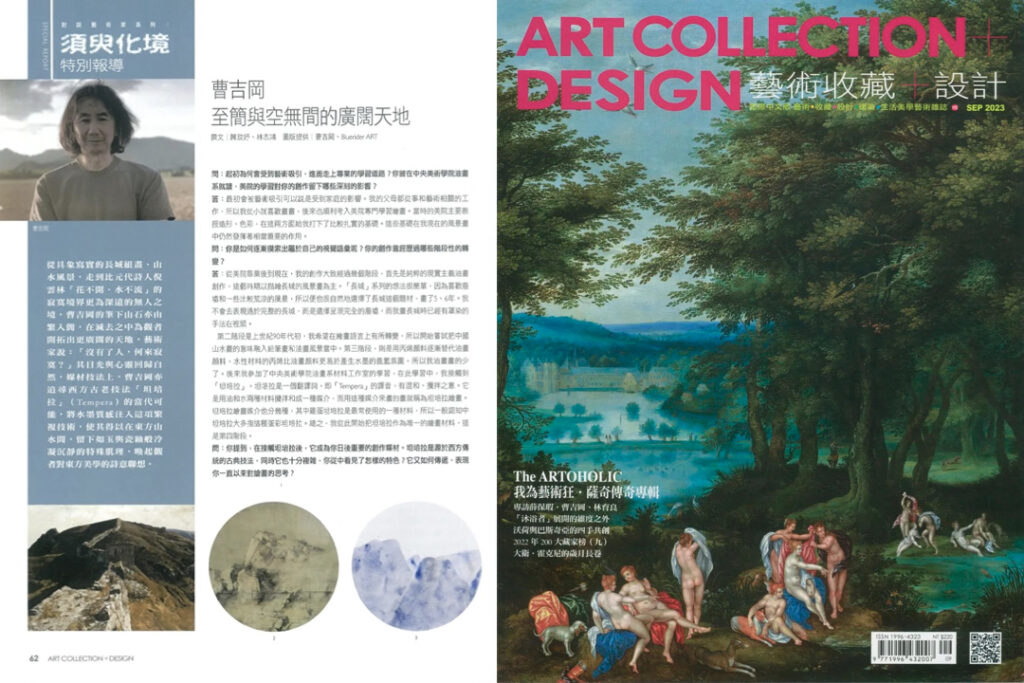

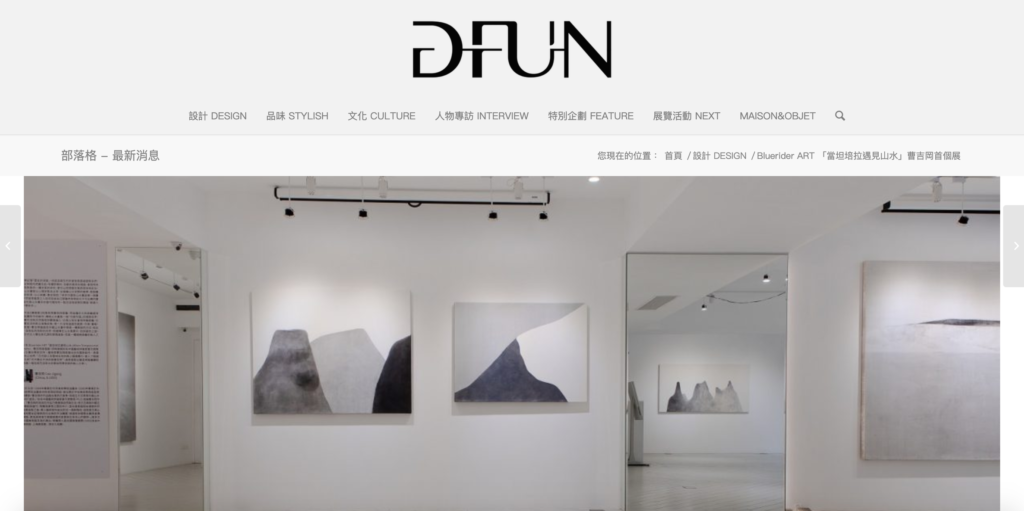

Cao Jigang, born in Beijing, China in 1955, graduated from the Oil Painting Department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 1984. In 2000, he completed the Material Expression Research Program at the same academy. He has previously taught at the Basic Department of the Sculpture School at the Central Academy of Fine Arts and currently resides and creates art in Beijing. Cao Jigang's artistic journey has evolved through various phases, initially depicting the ruins of the Great Wall in oil paintings. Over the years, he has explored different mediums such as pencil and acrylic, ultimately delving into the Egg Tempera technique to create large-scale works like the seven-meter-long "Guangling Melody" and the series "Barren Cold." His works are characterized by a unique semi-transparency, a warm, porcelain-like texture reminiscent of jade, achieved through deliberate layering. Expressing the concept of "emptiness" through intentional application, Cao Jigang has recently transitioned towards a minimalist style, opening up a space for contemplation on the connection between heaven and humanity. He received the Silver Award at the 9th National Art Exhibition of China in 1999 and has participated in numerous exhibitions at institutions such as the China National Art Museum and internationally. His works are permanently collected by prestigious institutions like the China National Art Museum, Shanghai Art Museum, as well as by numerous collectors from both sides of the Taiwan Strait.

Zhuzhong Art Museum, Beijing

National Art Museum of China, Beijing

曹吉岡 Cao Jigang的繪畫功底扎實而深厚,四十年的創作生涯歷經不同時期創新演變,包括以下四階段不同時期:

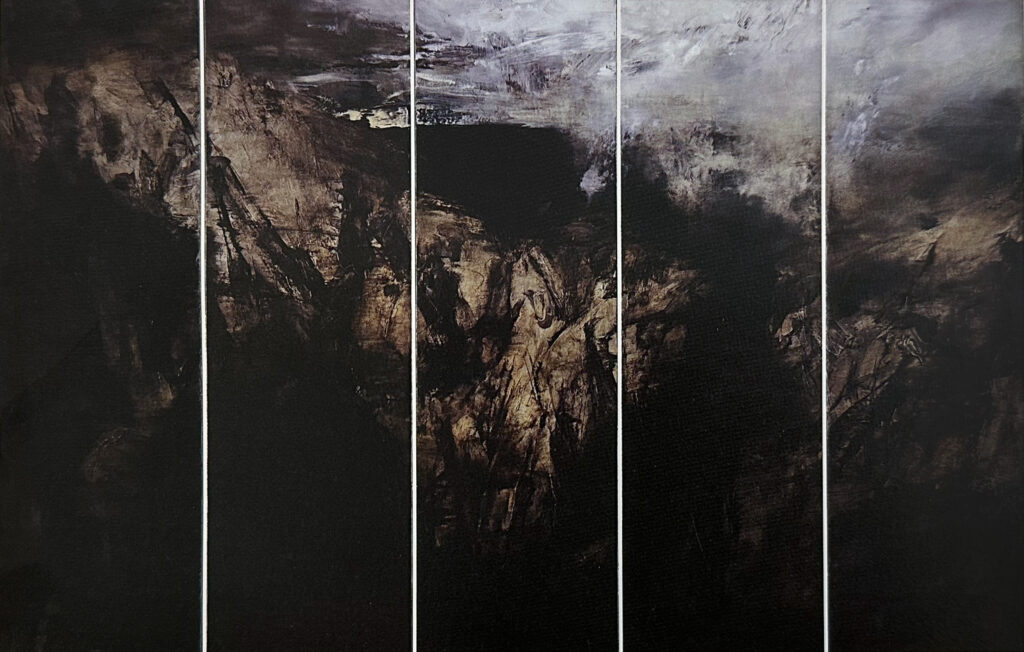

The First Stage "Oil Painting of the Great Wall" period: In this phase, Cao Jigang employed the pure language of European oil painting to depict the "Great Wall" series. Within the paintings, the artist replaced the intact Great Wall with desolate ruins, conveying a sense of defeat through the painterly qualities. Additionally, during this period, the artist began to incorporate the technique of glazing.

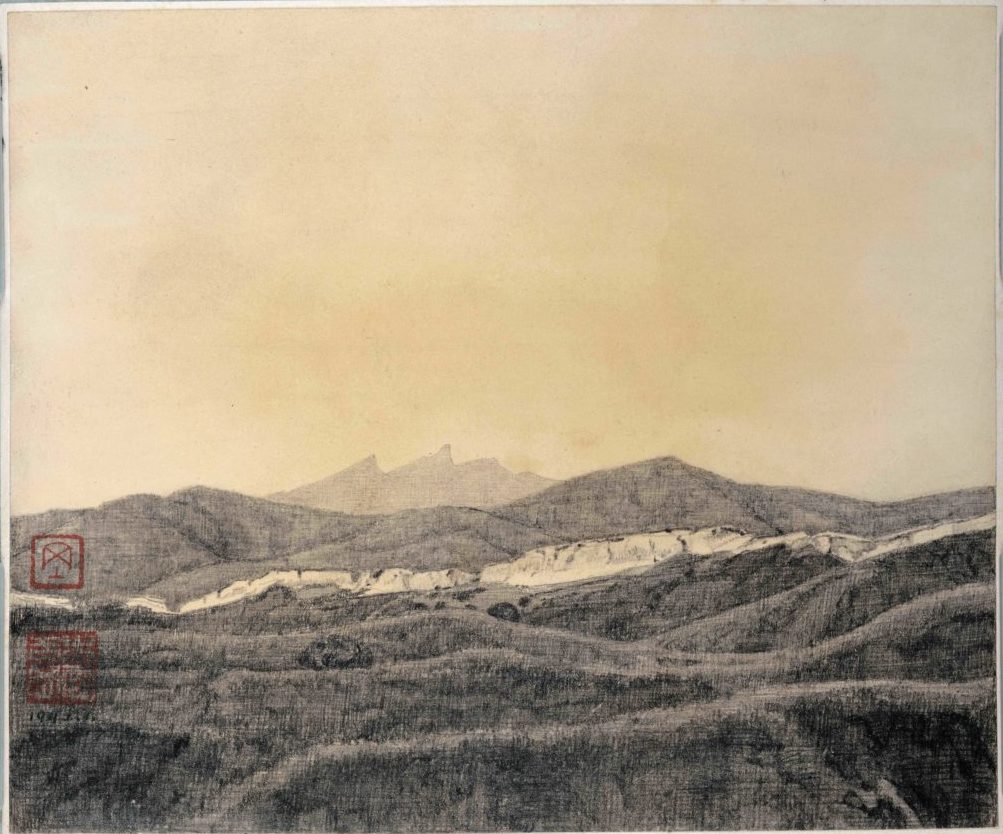

The Second Stage "Pencil Drawing Landscape Transformation" period: During the pencil period, a transition occurred towards an intermediate stage focused on landscape transformation. Innovating pencil techniques, the artist combined landscapes and scenery, portraying the scenery in a long rectangular composition from top to bottom, reminiscent of ancient landscape depictions. This approach generates a majestic and grand atmosphere in the style of classical Chinese ink wash painting.

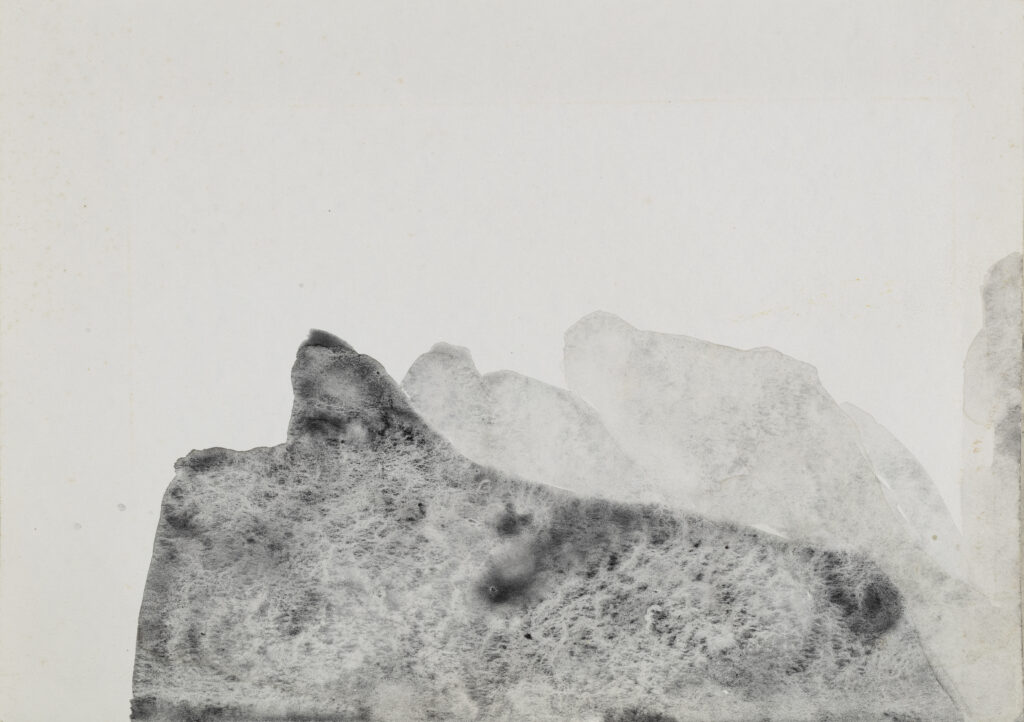

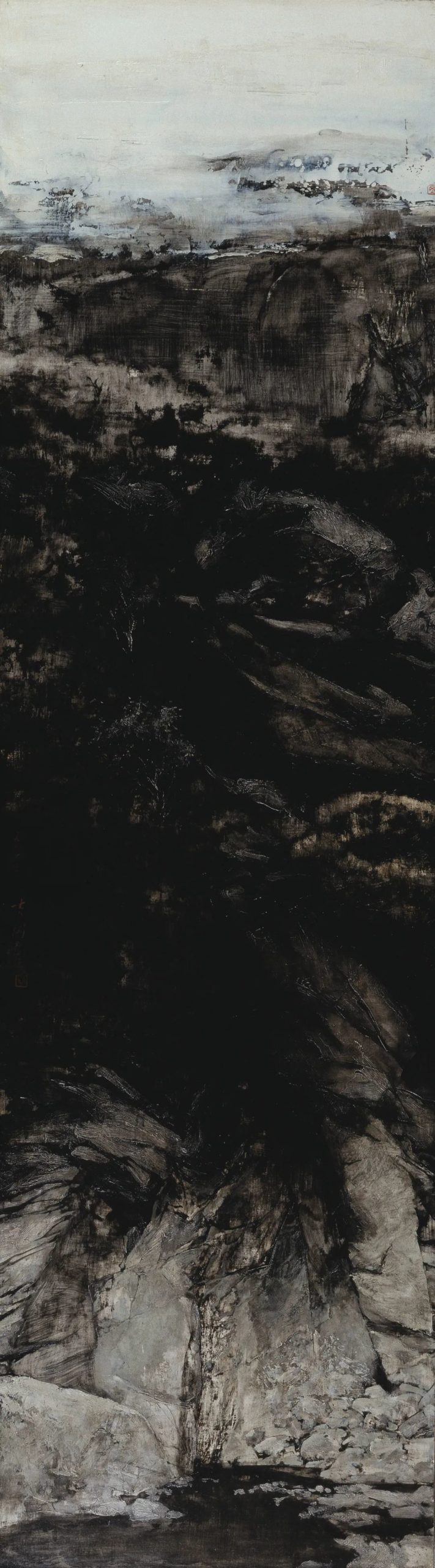

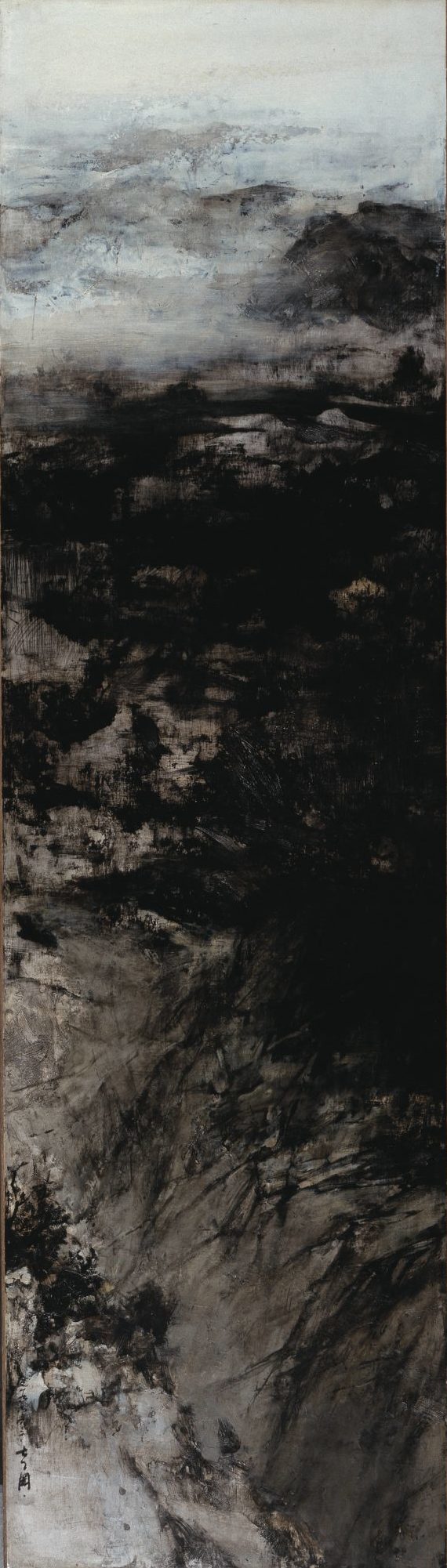

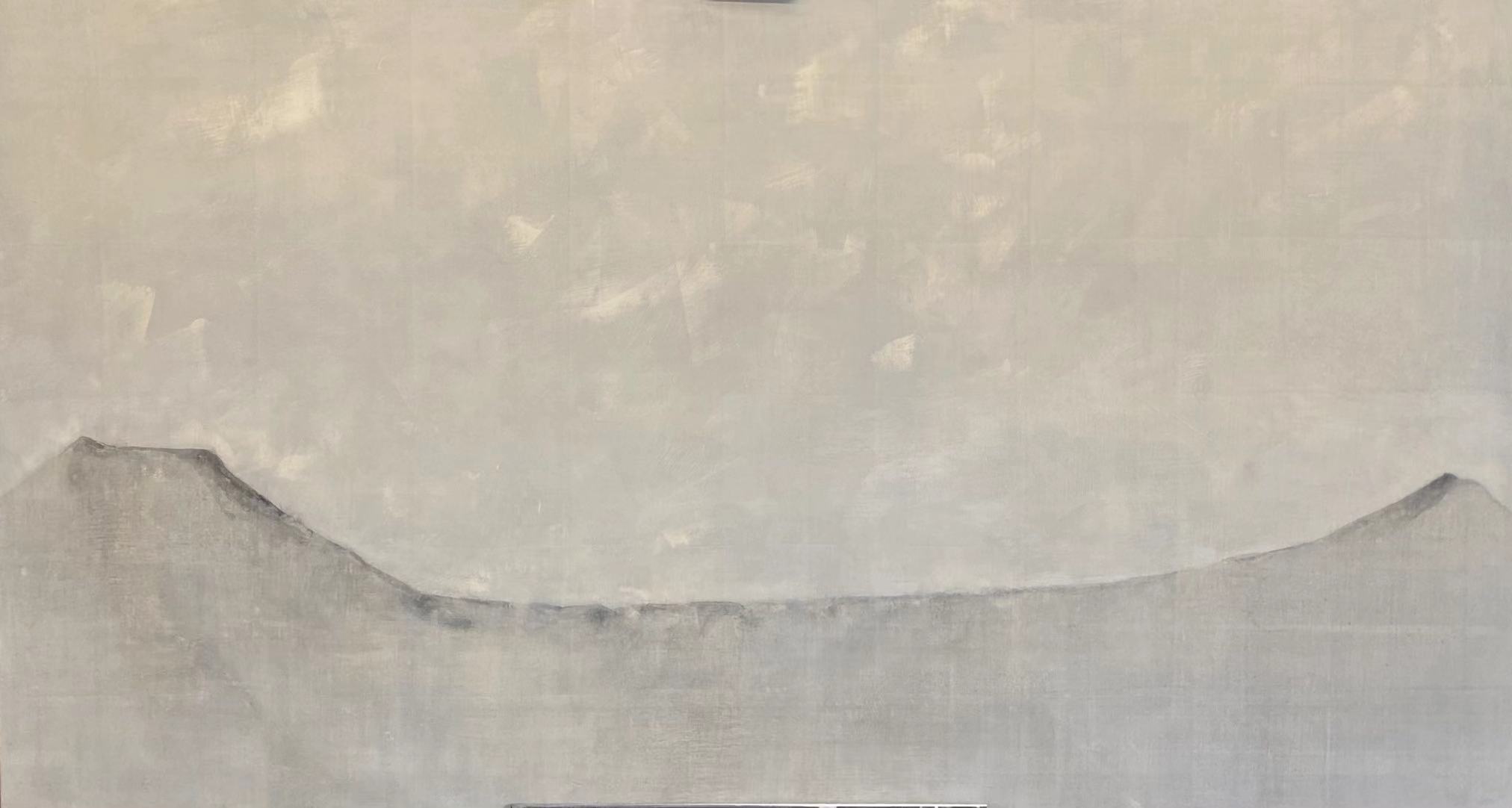

The Third Stage "Acrylic Landscape Painting" period: During this period, Cao Jigang transitioned from sketching landscapes in low-altitude southern regions of south to gradually ascending to higher altitudes with expansive views of plateaus. The painting perspective began to open up and simplify as the artist moved towards higher altitudes. Utilizing the oily properties of acrylic paints, Cao Jigang introduced a misty effect in realistic landscape paintings, creating an ink-wash aesthetic. The landscapes are progressively transformed into traditional Chinese landscape painting "Shan Shui".

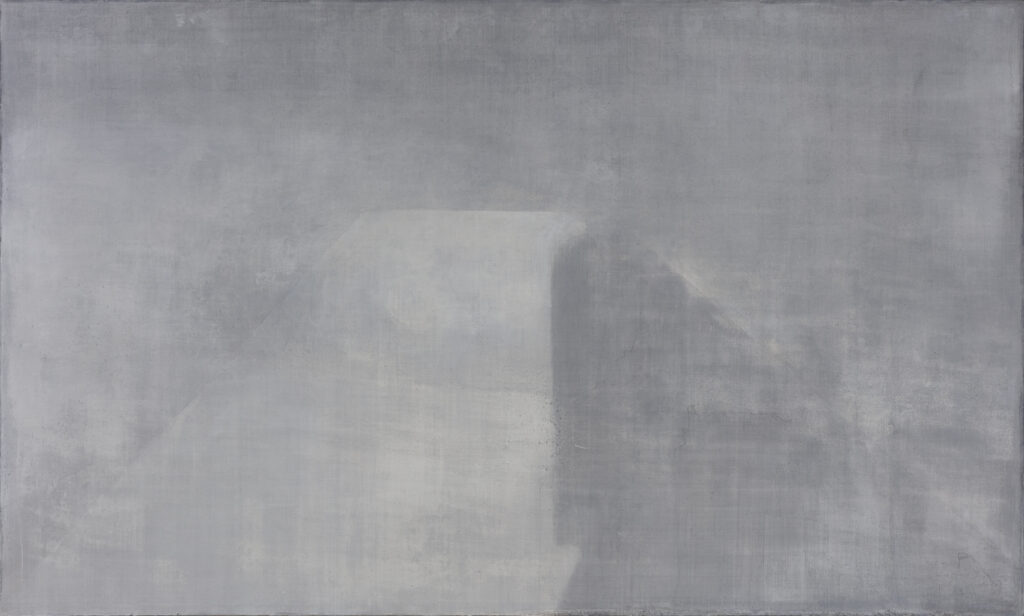

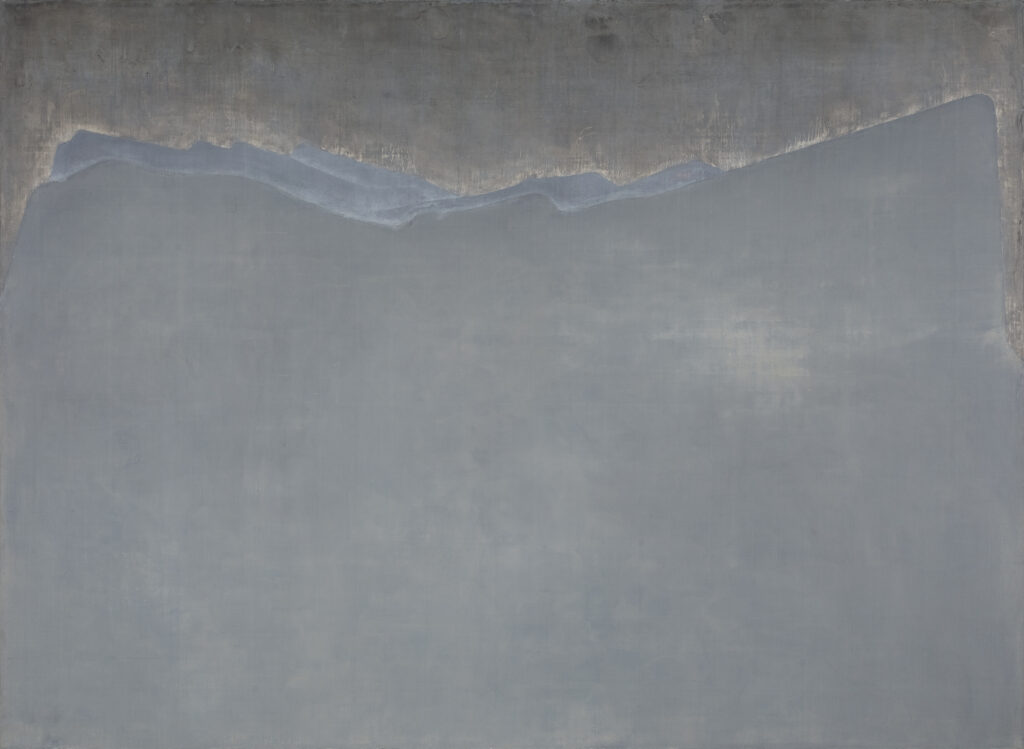

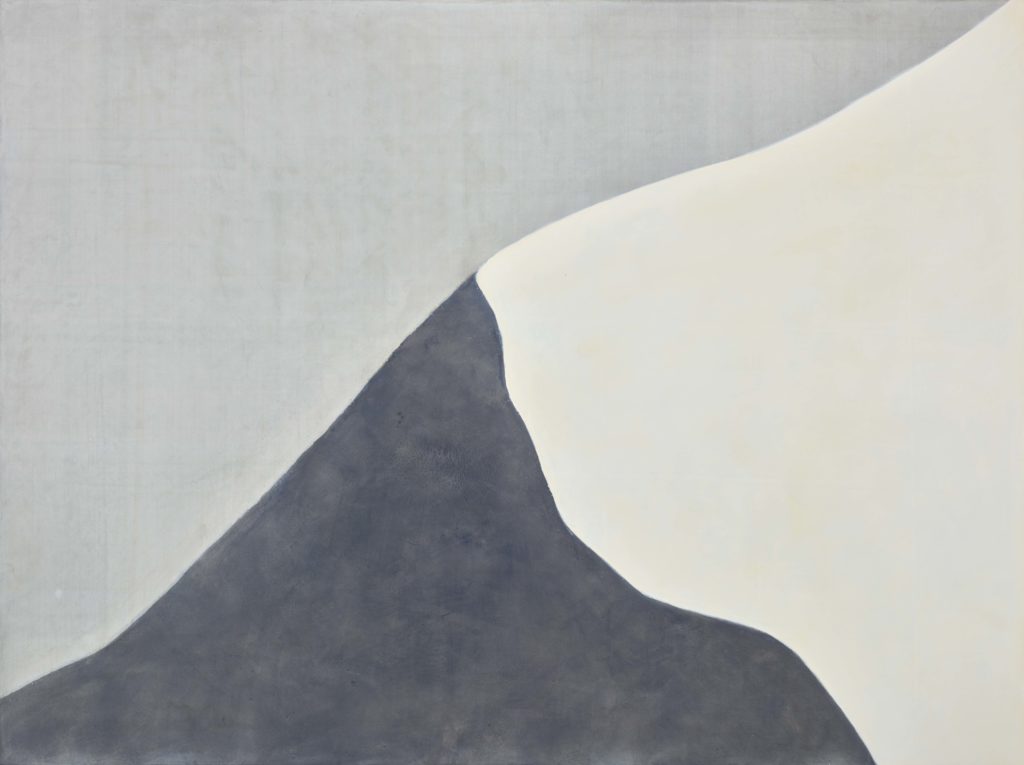

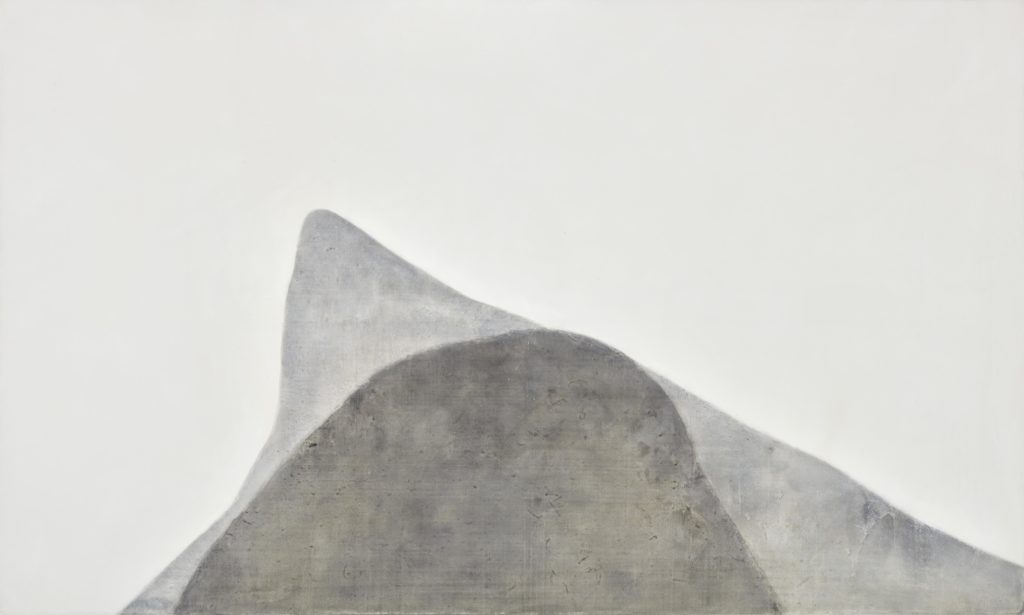

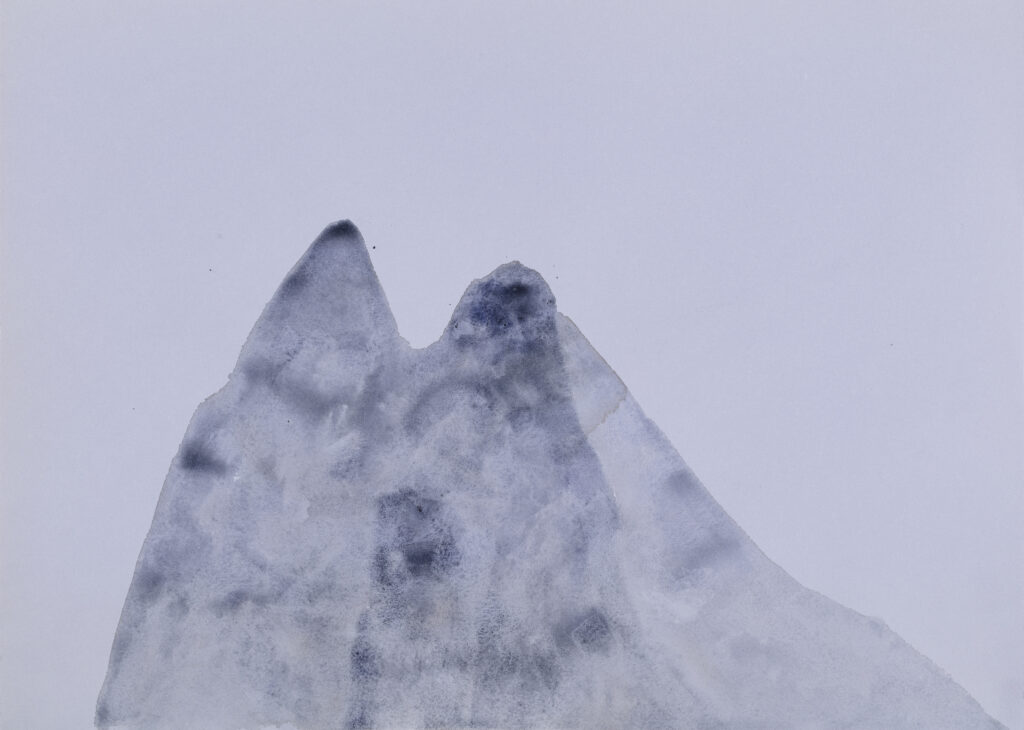

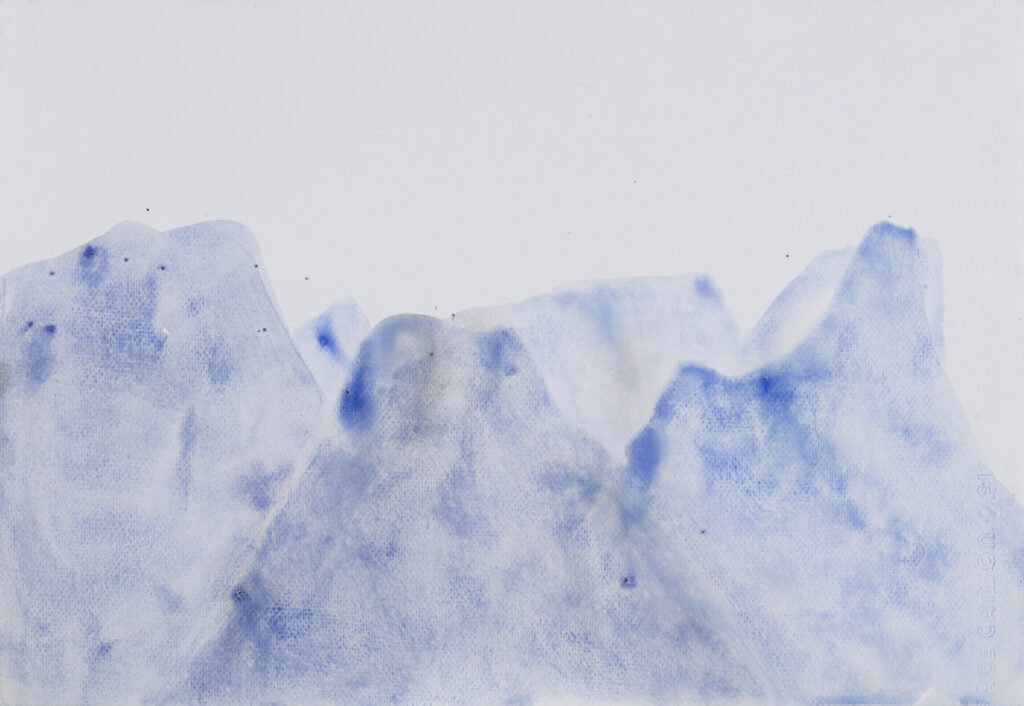

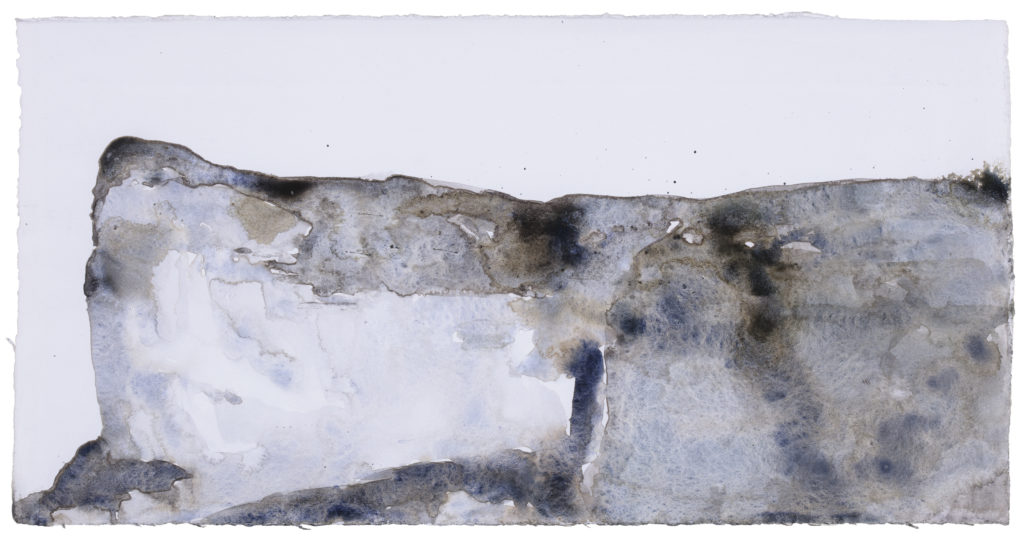

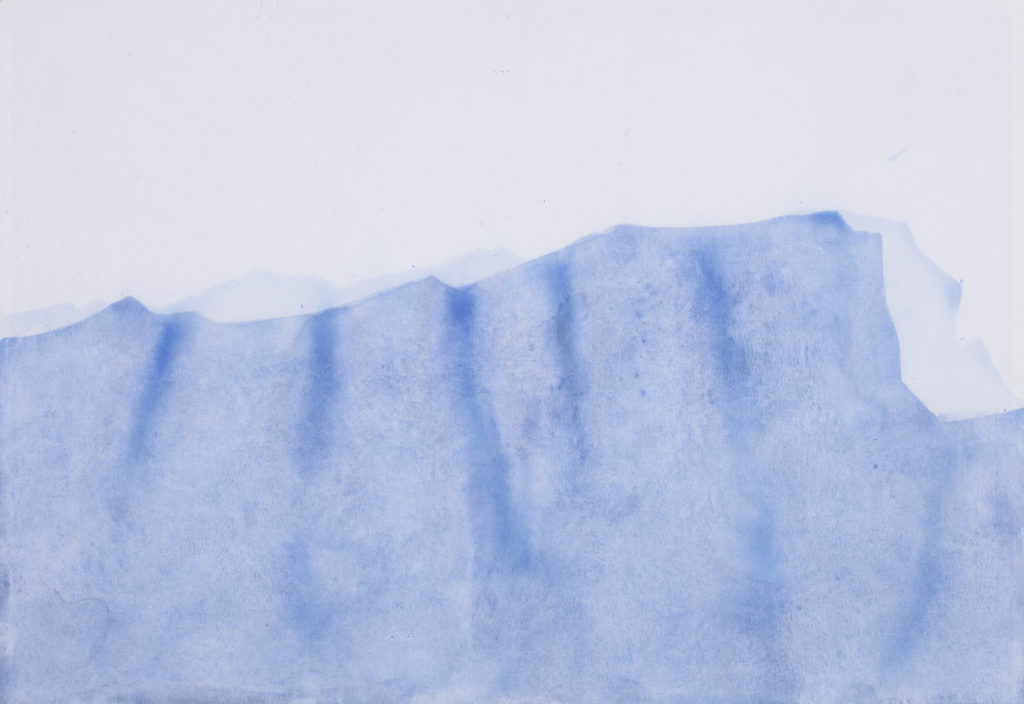

The Fourth Stage "Egg Tempera" period: Since the 1980s, Cao Jigang has dedicated himself to the study and improvement of the intricate and fading European ancient technique known as Egg Tempera painting. Choosing Egg Tempera for its irreplaceable aesthetic values, semi-transparency, internal luminosity, and a texture reminiscent of porcelain glaze or jade, he appreciates its unique qualities. Due to its semi-translucent nature, one can discern details beneath the layers of color upon closer inspection, creating a sense of permeation. Similar to a meditative practice, the technique involves multi-layered polishing. Drawing inspiration from the glazing method in traditional Chinese ink wash painting, Cao Jigang retains the flowing quality of ink with thin layers. The resulting artworks, such as the monumental seven-meter-long landscape painting "Guangling San" which reference the classical Chinese tale of Ji Kang playing one last melody on the gugin before his execution, and the impactful series "Barren Cold," exhibit a semi-translucent internal luminosity and a warm, porcelain-like jade texture.

Egg Tempera, a painting technique using egg yolk or egg white mixed with pigments, was prevalent during the European Renaissance (14th to 16th centuries), employed by masters such as Da Vinci, Caravaggio, and Rembrandt. Cao Jigang redefined traditional Egg Tempera materials and methods, finding a balance between the solidity of Western painting and the fluidity of traditional Chinese ink wash painting. Chinese landscape painting, inspired by Taoist philosophy, embraced the concept of "unity of Tao and nature," which was popular among poets and painters. Cao Jigang ‘s works blend the solemn elements of isolated landscapes with the spontaneity of nature during plein air sketching. Whether portraying stark contrasts in monochrome or neutral grays with almost no emotional tone, his minimalistic approach resembles the subtle traces of passing time.

Bluerider ART kicks off 2024 Programme with the touring exhibition Cao Jigang Skypath at Taipei • Dunren and Renai. Apart from showcasing several new large-scale works, this exhibition expands upon the previous solo exhibition at Shanghai • The Bund by including representative works from different phases. Additionally, the exhibition showcases some personal art tools selected by Cao Jigang, inviting the audience to journey through the artist's 40-year-long creative process, from the ruins of the Great Wall to the mournful melody of "Guangling Melody"; from the tranquil landscapes to the chilling void of "Barren Cold." Through transcending earthly confines on the "Skypath", experience how Cao Jigang integrates his spirit, emotions, and insights into nature, connecting individuals with nature through art and ultimately reaching the path of unity between individual life and the universe, as expressed in Taoist philosophy: "Harmony between Heaven and Man, Unity of Nature and Humanity."

Education

1984 Oil Painting Department of Central Academy of Fine Arts

2000 Oil Painting Materials Researcher Studio, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing

Selected Exhibitions

2024 ”Cao Jigang: Skypath” Touring Exhibition, Bluerider ART, Taipei

2023 "West Bund Art&Design" Solo Show, Bluerider ART, Shanghai, China

2023 "Homeland Universe" Group Show, Bluerider ART, London, UK

2023 "Skypath" Solo Show, Bluerider ART, Shanghai, China

2022 "Taipei Dangdai" Solo Show, Bluerider ART, Taipei

2021 "White + White — Contributions to Chinese Art", Artron Art Centre,

Shenzhen, China

2021 "JINGART" Two-Person Exhibition, Bluerider ART, Beijing, China

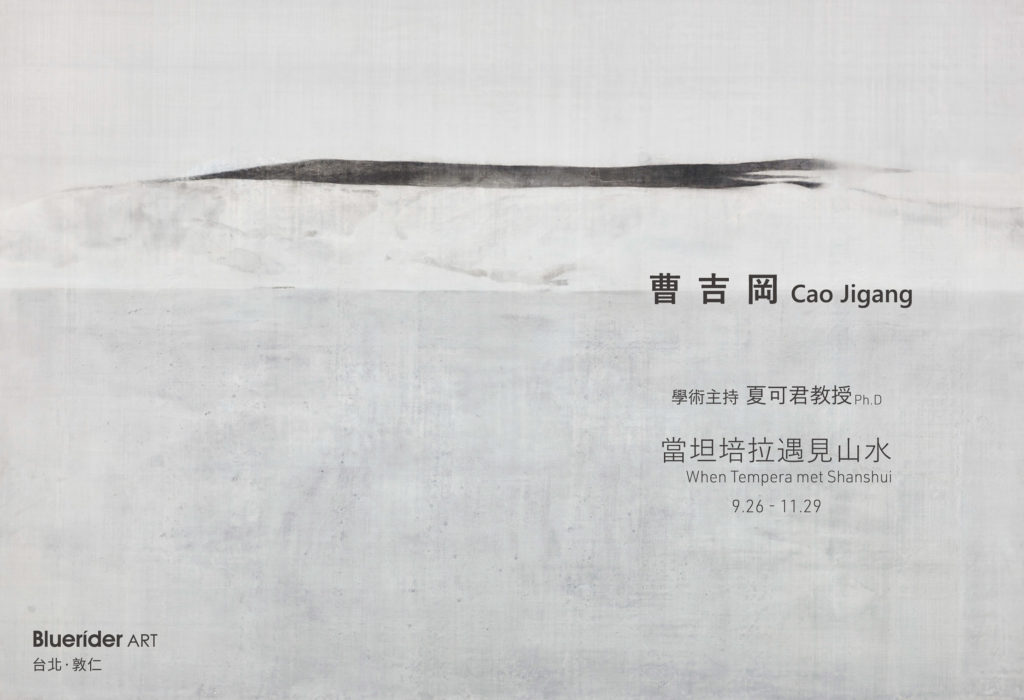

2020 "When Tempera Met Shanshui" Solo Show, Bluerider ART, Taipei

2020 "White into Blank" Group Show, 798 Art District Whitebox Art Center,

Beijing, China

2019 "Cao Jigang Solo Show", No. 8 Bridge, Shanghai, China

2018 "Parallel Horizons — Chinese Oil Painters with European Peer Exchange

Exhibition", Bastille Design Center, Paris, France

2018 "The Fifteen Sceneries" Solo Show, Zhuzhong Art Museum, Beijing, China

2015 "Cao Jigang Little Painting Works Exhibition", Zhuzhong Art Museum,

Beijing China

2014 "In the Silence Between Two Waves" Group Show, BRIC Art Space, Italy

2014 "French National Artists Association International Art Salon Exhibition"

Group Show, Louvre Museum, Paris, France

2014 "Empty Cold: Chora-topia of Nature", SOKA Art, Beijing, China

2014 "Abstraction and Nature", Zhuzhong Art Museum, Beijing, China

2014 "To Explore the Pace" Group Show, Jinan Art Museum, Shandong, China

2013 "Darkness Visible: Group Show of Ten Artists from China and US", National Art Museum of China, Beijing, China

2012 "IN TIME—Chinese Oil Painting Biennale", National Art Museum of China,

Beijing, China

2012 "Vaulting Limits", Tenri Cultural Institute, New York, USA

2011 "Giving and Receiving", University of Colorado Art Museum, Los Angeles,

USA

2009 "Transforming Pictures: A Contemporary (Re)presenting of Traditional

Thoughts, National Art Museum of China, Beijing, China

2008 "China in Paintings-Exhibition of Cao Jigang's Paintings Created in His

Phases of Creation", National Art Museum of China, Beijing, China

2008 "In Depth: CAFA 5 Artists Exhibition", Today Art Museum, Beijing, China

2007 "Eastern Vision – Sino-Korean Modern Art Exhibition", China Millennium

Monument, Beijing, China

2007 “Facing and Dealing: Sino-Us Artist Exhibition”, National Art Museum of China, Beijing

2003 "Beijing International Art Biennale", National Art Museum of China,

Beijing, China

2001 "Conversation between Durer and Chinese Landscape Painting" Cao

Jigang's Works on Paper Exhibition, SOKA Art, Beijing China

2001 "The Voice of Years" Group Show, Shanghai Fine Art Museum, Shanghai,

China

2000 "Chinese Landscape Painting Exhibition", Hosted by the China Artists

Association, Finland

1999 "The 9th National Fine Arts Exhibition" ("Sea-like Mountain"-Silver

Award), Beijing, China

1999 "Beijing Fine Art Exhibition For 50th Anniversary of Funding PRC"

("Sea-like Mountain"- Outstanding Award), National Art Museum of

China, Beijing, China

1998 "Chinese Landscape Oil Painting Exhibition", National Art Museum of

China, Beijing, China

1996 "The First China Oil Painting Society Exhibition", National Art Museum of

China, Beijing, China

1994 "Xinzhulian Chinese Traditional Paintings and Oil Paintings Exhibition"

("Deep Valleys and Shallow Streams"-Silver Award), National Art

Museum of China, Beijing, China

1992 "Cao Jigang Solo Show", National Art Museum of China, Beijing, China

1990 "Oil Painting Group Show", Hao Zhen Gallery Pte Ltd, Singapore

1989 "The 7th National Exhibition of Fine Arts" ("The Great Wall Series -

Desolate Garrison), Shanghai, China

Awards

2014 French National Artists Association International Art Salon Exhibition-

"Lion Grove"- Gold Award

1999 The 9th National Fine Arts Exhibition-"Sea-like Mountain"-Silver

Award

1999 Beijing Fine Art Exhibition For 50th Anniversary of Funding PRC-

"Sea-like Mountain"-Outstanding Award

1994 Xinzhulian Chinese Traditional Paintings and Oil Paintings Exhibition-

"Deep Valleys and. Shallow Streams"-Silver Award

Collections

2009 "The Hua Shang Mountain" by National Museum of China

2008 “The Great Wall Series I”by National Museum of China

2001 “Autumn Mountain” by Shanghai Fine Art Museum

1997 “The Forest” by China International Exhibition Agency

1995 “Woman Nude”by China International Exhibition Agency

1995 “The Great Wall Series” Thunder by China International Exhibition Agency